In his introduction to the Woody Guthrie songbook, From California to the New York Island, Pete Seeger encourages singers to “be yourself” and discourages them from trying to imitate Guthrie’s accent and his “flat vocal quality” when performing his songs (1960, 3–4). Content warning: this article will discuss songs that address difficult topics including death and suicide. I have added a * beside the headings for songs with sensitive topics. Seeger instead recommends a musical immersion in Guthrie’s repertoire and familiarity with its quintessential style of “simplicity” and “matter-of-fact, unmelodramatic” musical statements (1960, 4). I am indebted to Rings (2013, [24]) for first bringing this songbook commentary to my attention. Rings’s study also cites that Seeger’s text is quoted in Heylin’s (2011, 82) study of Bob Dylan, “which also notes Dylan’s highlighting of the passage” in his own copy of the songbook.

In advocating for greater engagement with Guthrie’s style, Seeger suggests two things that are of particular interest for the present study. First, Seeger promotes knowledge of the “American Folk music” genre “to which Guthrie’s music belongs” and directs singers to Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music (a 1952 Folkways Records release of recordings from 1926–1933) as a stylistic source if they are “in doubt about how to perform a number” (1960, 4). Seeger (1960, 4) also mentions that Guthrie recorded “many of the songs” from the Anthology himself. Second, he cites “irregularity” as a performance feature that singers can “learn from Woody’s method of performance”(1960, 4). Metric irregularities are also common features of old-time and country music. Neal (2002) finds expressive irregular meter in the music of Jimmie Rodgers; Rockwell (2011) analyzes multiple occurrences of stylistically “crooked” meter in the Carter Family songs. Seeger notes a particular type of irregularity these singers should notice and imitate when repeating strophic melodies. He explains,

Woody, like all American ballad singers, held out long notes in unexpected places, although his guitar strumming maintained an even tempo. Thus no two verses sounded alike (1960, 4). Seeger also discusses general features of irregular meter like extra beats added to measures and melodies changing “rhythmically from verse to verse, to fit the words exactly” (1960, 4).

Though not clearly stated in this songbook introduction, Seeger is directing his readers to a common rhetorical technique that occurs in the two repertoire sources he is discussing. The “long notes” “held out” in “unexpected places” arise both in Guthrie’s music and on Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music (hereafter, the Anthology). These unexpectedly long melody notes are a noteworthy rhetorical performance strategy in these musical sources, with the held melody note halting melodic progress (and sometimes the harmonic rhythm) while the accompaniment keeps strumming. The effect is one of continued rhythmic momentum while fermata-like melody notes pause the melodic and harmonic trajectory: stylistic metric quirks that involve both motion and stasis.

Long-held melody notes are striking enough from their presence in folk revival sources to warrant investigation. But similar types of held notes also arise in Bob Dylan’s early 1960s songwriting, making them an extra source of interest for an investigation of the metric rhetoric of American popular music. Indeed, it is in Dylan’s music where I first encountered the technique, while studying his use of irregular meter in performance. For more on the self-expressive use of flexible meter in songs by Dylan’s and his singer-songwriter contemporaries, see Murphy (2023).

Indeed, Seeger’s two points are of particular interest when viewed through a retrospective lens, because both Guthrie’s repertoire and Smith’s Anthology are cited as direct influences on Bob Dylan’s developing 1960s folk style. Studies of irregularity in Dylan’s music position folk revival sources as important stylistic sources for the singer’s metric rhetoric. For example, Murphy (2023, 18–21) discusses the impact of folk revival sources on Dylan’s self-expressive flexible meter. For more on Dylan’s general stylistic influences, see Harvey (2001). Yet these unexpected long-held melody notes over continued strumming—which have clear influence on Dylan and occur with provocative effect in his songs—are largely unexplored as an expressive metric technique in his folk-inspired 1960s repertoire.

In this article, I embark on a short study of these ideas. I theorize long-held-note techniques as performed-out fermatas, relating them to the concept of “composed-out fermatas” observed in Classical-period orchestral music. Many thanks to Joti Rockwell for the suggestion of “performed-out” (rather than “composed-out”) as better suited to this popular music repertoire. In doing so, I identify two types of performed-out fermatas and one related technique: (1) performed-out fermatas that occur mid-phrase, usually just before the pick-up to a hyperbeat, (2) anacrusis-type fermatas that elongate the pick-up to a hyperdownbeat, and (3) the related technique of elongated harmonic zones, wherein a long-held harmony has the effect of pausing momentum of the harmonic rhythm in a fashion similar to, and sometimes combined with, a held melody note. I analyze examples from Guthrie’s repertoire alongside several artists featured in the Anthology and position these as sources for how performed-out fermatas seeped into Dylan’s 1960s repertoire at a crucial moment in his development as a songwriter: between his practice of adapting folk songwriting and his innovations with original compositions.

The primary goal of this work is to argue that these unexpected long-held melody notes are techniques by which these artists added interest and aliveness to strophic song performance. The use of performed-out fermatas among the artists in this study suggests that the technique is an important element of metric rhetoric in the folk revival genre: transmitted to, and kept alive by, Dylan. A secondary goal of this brief study is to invite further investigation of the metric rhetoric of folk revival sources, particularly the rhetorical techniques that have been transmitted from revival sources to mid-century popular music. The presence of performed-out fermatas in Dylan’s 1960s music is simply one thread of lasting influence between early twentieth-century recordings and the future of American popular songwriting.

Woody Guthrie's performed-out fermatas

In the early 1960s, singer-songwriters were inspired by sources in the folk music revival, during which there was a renewed interest in rural American folk and blues recordings from the early twentieth century. Woodrow Wilson “Woody” Guthrie—whose performances were recorded as early as 1940—was central to this revival for artists, such as Bob Dylan, who were part of a trend in which “traditional rural American music style and aesthetics were transmitted to young, urban musicians” (Harvey 2001, xix). Alan Lomax recorded Guthrie for the Library of Congress in 1940, alongside other field recordings for the album Anglo-American Ballads, Volume One. For more on Guthrie, see Reuss (1970). Indeed, Guthrie was a particularly important figure in Dylan’s musical ideology. Albin Zak (2004, 623–624) describes Guthrie as “mythic” emblem for “a central strain” of Dylan’s musical experience.

Guthrie, "The Gypsy Davy"

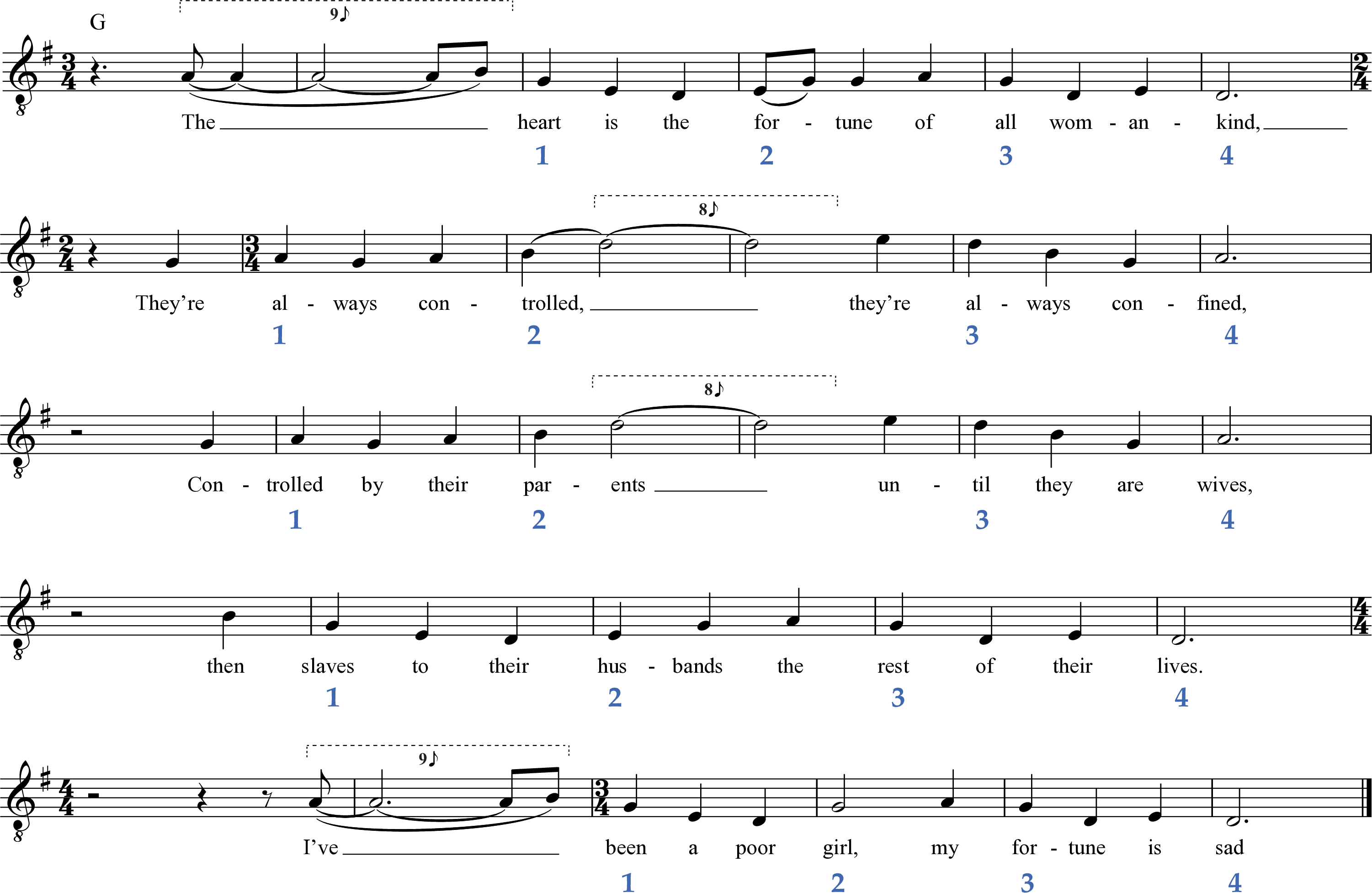

Guthrie’s use of the performed-out fermata will serve as a starting point for theorizing both the concept and how it adds interest to strophic song performance. His 1940 recording of the song “The Gypsy Davy” (Example 1) provides one of the earliest recorded occurrences in his repertoire, released on the Library of Congress recording Anglo-American Ballads, Volume One (1941). The song was likely based on the Child Ballad (No. 200) “The Gypsy Laddie” which dates to the 1700s. Guthrie’s refrain of “gone with the Gypsy Davy” has similarities to Version C in the Child Ballads (Child 1882, 67), which includes the line “She’s awa wi Gipsey Davy!” as the final line of stanza 8. Multiple transcriptions of this song (from performances from 1916) are included in Campbell and Sharp (1917, 112–118). The lyrics in Guthrie’s version recount a woman planning to leave her husband for Gypsy Davy but struggling to do so if it means leaving her “pretty little blue-eyed baby.”

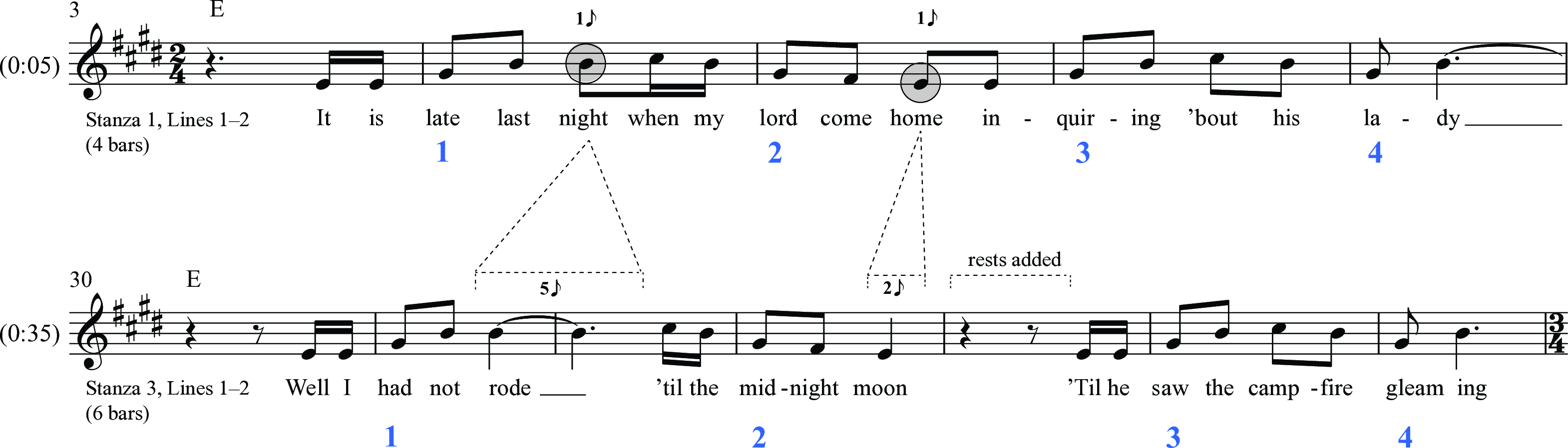

After a guitar introduction establishes a 2/4 meter in E major, the first vocal line—spanning lines 1 and 2 of stanza 1—articulates a prototypical four-bar unit that places stressed syllables on quarter-note beats, with the first of each pair as a downbeat. In later iterations of this melody, Guthrie holds some of these notes longer than expected, creating a sensation of fermata in the voice. But since his accompaniment maintains the established strumming pattern, the held note in the voice does not actually pause the musical progress—rather, it functions as a performed-out fermata that lengthens the prototype first heard in stanza 1. The underlying four-bar unit is still present (shown with the numbers below the staff), but the actual sounding length of the unit is now six bars because the held notes in the melody (on the mid-phrase words “rode” and “moon”—plus added rests) expand the unit lengths. Grey circles indicate which melody notes are elongated between stanza 1 lines 1–2 and stanza 3, lines 1–2. I have also included dotted brackets above the lower staff with annotations to show how much longer the melody notes are and where rests have been added.

Performed-out fermatas vs. composed-out fermatas

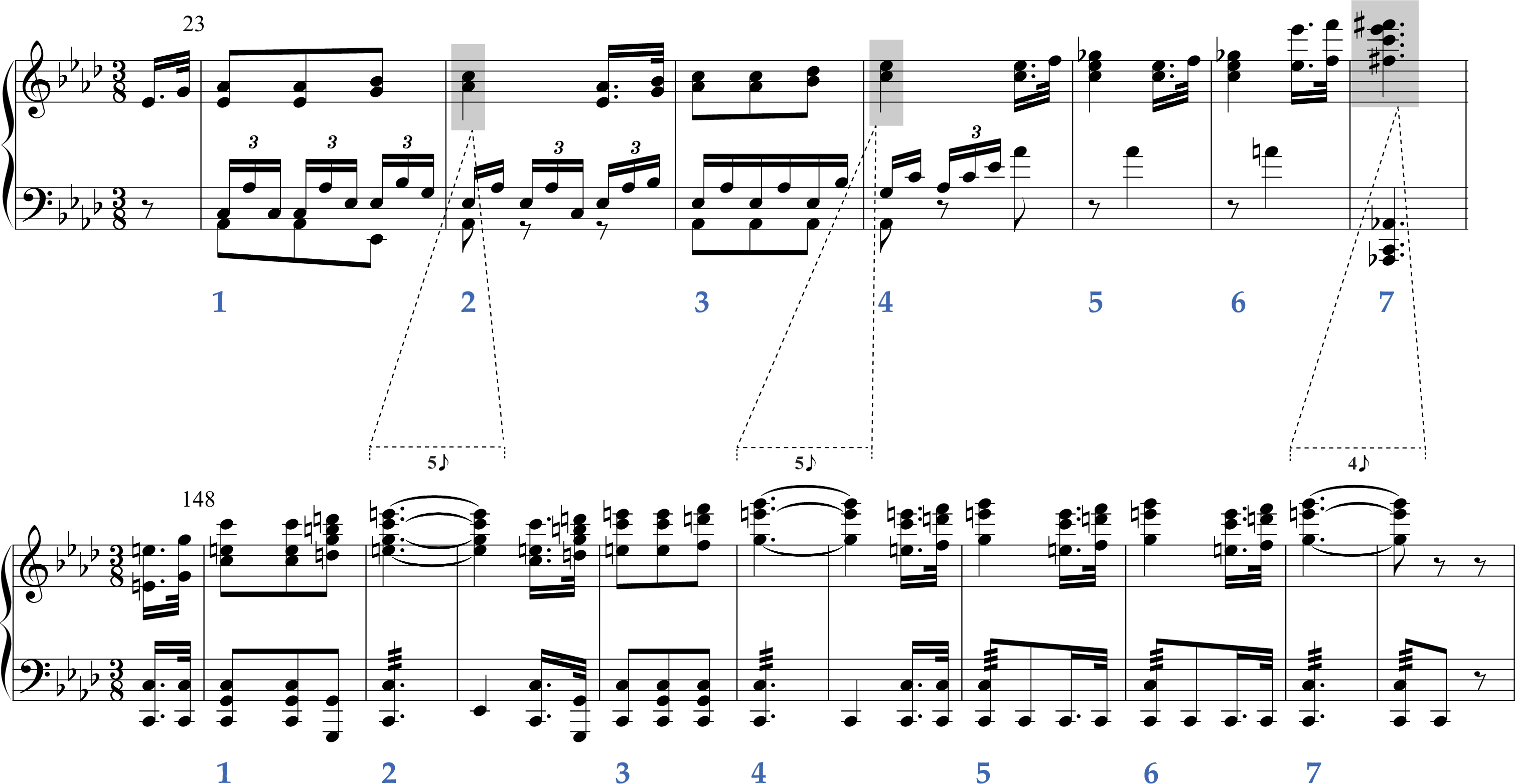

I use the term “performed-out fermatas” in this article as a modification of the technique of “composed-out fermatas” as theorized in William Rothstein’s Phrase Rhythm in Tonal Music (1989), which explores composed-out fermatas as a type of phrase expansion in nineteenth-century Western art music. Using a passage from Beethoven’s 5th symphony as an example, Rothstein (1989, 80–87) explains that this expansion type has arisen in theories of rhythm and meter since Kirnberger and involves long durations simultaneously having the impression of a fermata alongside being quantified by the added value of notated durations—rather than being represented in the score by fermata symbols. Everett (2008, 191) also observes the practice of composed-out fermatas as a method of phrase length irregularities in the music of the Beatles. In Example 2 I have re-illustrated Rothstein’s metrical interpretation using my own annotation style for the present study. Rothstein’s metric analysis follows a model of harmonic prolongation that compares these two passages with similar content but different metric identities. In mm. 23–29 (the upper system of Example 2), the material occurs across seven measures. In mm. 148–157, similar material is expanded through longer notated durations on the score. For example, the quarter-note duration in m. 24 becomes 2.5 quarter-note beats (or five eighth-note beats) in mm. 149–150. The term composed-out fermata is appealing here because these moments impart the sensation of a fermata without being notated as such in the score; instead the notation quantifies the rhythmic and metric expansion exactly.

If the longer notated durations in mm. 148–157 of Example 2 were notated as fermatas (instead of as sounding durations), it would not make sense to continue previously established counting patterns. Theorists of musical meter agree. As Wallace Berry suggests, with fermatas (as with cadenzas), “it defeats demonstrable functional purpose to project a continuing, regular pulsation and no sensitive performer would do so” (1987, 364). William Benjamin presents a similar argument, theorizing fermatas as a kind of “standing still” but clarifies that it is not time that stands still but counting. Benjamin explains: “In a fermata, the metric flow at all levels is suspended; the counter stops counting but keeps track of where he was in his count . . . A fermata applied to a metric span always lengthens that span in an objective sense—often to a marked extent—but never increases the distance of its initiating beat from the next one on the same level in a metric sense” (1984, 397). When fermatas are composed-out, it instead invites a continuation of counting. Composed-out fermatas, as with the performed-out fermatas we will encounter in this study, invite a dual conception of stasis (a sensation of pause) and motion (an invitation to count the length of the pause).

In music from the folk revival, a primarily oral tradition, I consider these fermatas as performed-out by the singer—with the potential for this choice to be spontaneous and change between performances—rather than being composed-out by the songwriter with prescribed locations and lengths notated on a score. Despite these ontological differences, performed-out and composed-out fermatas have a similar effect on counting. In the examples in this study, I illustrate long-held melody notes as pausing hypermetric counting, which creates a sense of suspended time, and I transcribe the sounding durations as they occur in the recordings from the continued accompaniment strumming. To simplify these diagrams and for ease of comparison between verses, I have not included accompaniment in these transcriptions but have shown chord changes above the staff. In some cases, I have simplified melodic rhythms but made an attempt to retain accurate downbeat placements. I encourage readers to listen to the recording clips and follow along with my vocal transcriptions to hear the accompaniment strumming patterns.

Comparing performed-out fermatas with conceptual or actual prototypes

Guthrie, “Pretty Boy Floyd” (1940)*

Rothstein’s comparison between a notated prototype and a notated composed-out fermata also works well for analyzing performed-out fermatas in Guthrie’s “The Gypsy Davy” (discussed above; Example 1). In that song, the prototype occurs during the first line and immediately becomes a point of reference for the rest of the verses, which sometimes include long-held notes in the vocal line. A similar situation occurs in Guthrie’s song “Pretty Boy Floyd” from his album The Dust Bowl Ballads (1940). This ballad is about the late-1920s Oklahoma bank robber Charles Arthur Floyd, an outlaw whose crimes allegedly included killing a deputy sheriff. Yet Floyd earned a good public reputation for apparently having destroyed mortgage documents during his robberies. Guthrie’s characterization of Floyd as a “Robin Hood” type character is a major critique of his “Pretty Boy Floyd” lyrics, which elaborate on Floyd’s biography for the appeal of a “good outlaw” narrative. For more on Guthrie and this song, see Reuss (1970, 287). Guthrie positions Floyd’s illegal actions as manifestations of one type of robbery (with “a six-gun”) that contrasts with the other types, like when banks foreclose on homes, robbing people instead “with a fountain pen.”

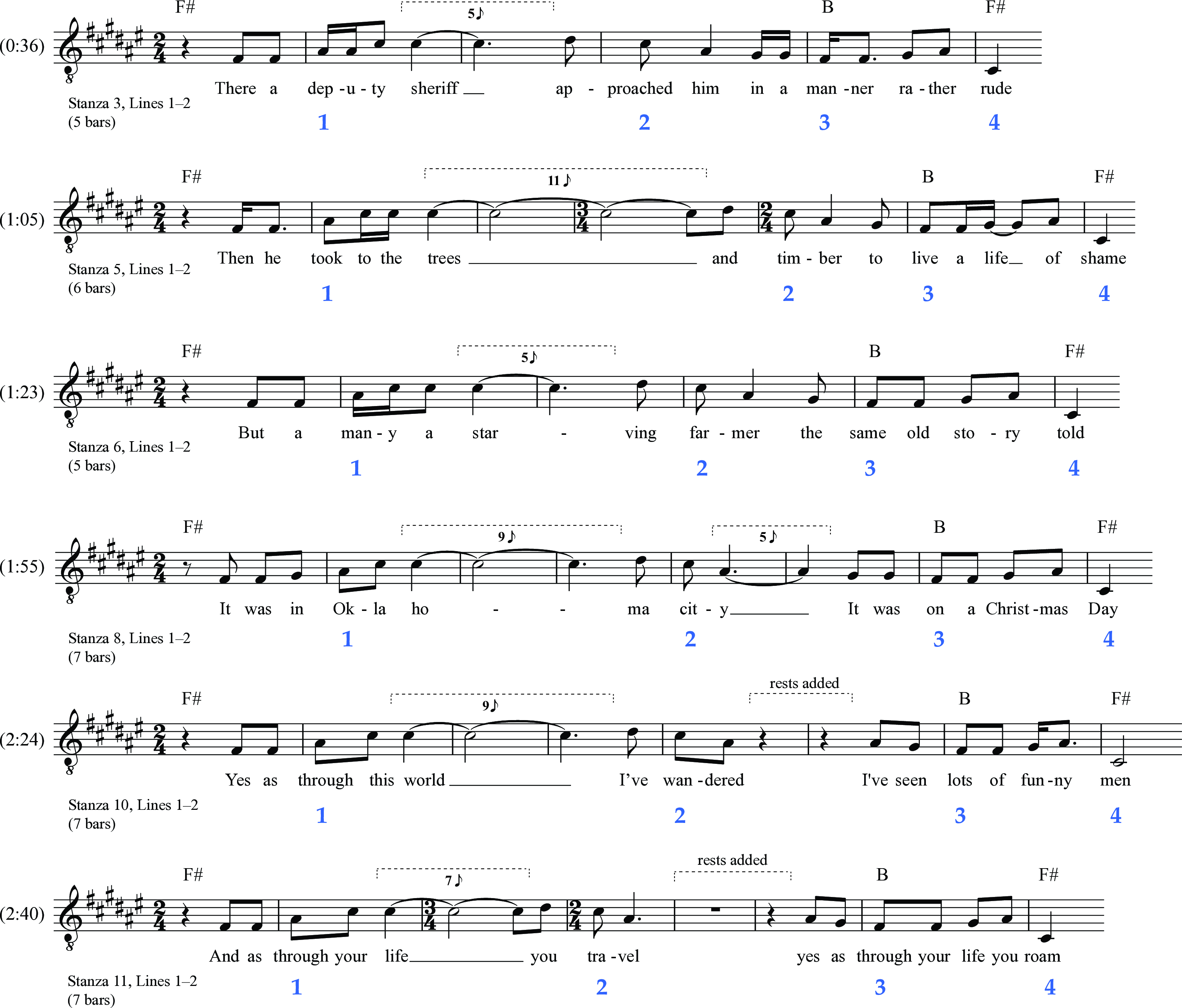

The song’s first melodic line (Example 3), which sets the first two lines of the stanza) is a metric prototype for the performed-out fermata techniques in subsequent stanzas of Guthrie’s performance. This first melody is a metric but not a melodic prototype for the passages that follow. It sets A♯3-C♯4-D♯4-C♯4 rather than the A♯3-C♯4-C♯4-D♯4 melodies of the lines that occur in subsequent stanzas. The first long-held notes in his melody occur in the first two lines of the second stanza (Example 3 [bottom]) where Guthrie holds the C♯4 melody note on the word “town” for a duration of seven eighth notes. The resulting vocal phrase is five bars long, with an expanded first half that shifts the expected harmony change from the would-be third measure to one bar later (at “Saturday”). I will return to this technique later in the section on elongated harmonic zones. Guthrie is indicating here that there will be an unpredictability to his performance of this song. And indeed, subsequent verses explore other ways to add variation to the strophic form through performed-out fermata techniques: every subsequent performed-out fermata (shown in Example 4) occurs on the first C♯4 melody note of the phrase. In stanza 8, Guthrie also includes a long-held note on A♯4 (at the second syllable of “city”). And in other locations (stanzas 10 and 11), he includes rests between the first two lines of the stanza to expand the unit, further delaying the arrival of IV.

Both “The Gypsy Davy” and “Pretty Boy Floyd” demonstrate the impact of Guthrie’s performed-out fermata techniques. First, they add interest and variety to his strophic song performances, changing the content between stanzas to avoid an exact repetition of material. Second, the long-held melody notes give the effect of unpredictability and potential humor to Guthrie’s storytelling rhetoric. Commentary from other folk-ballad sources point to “pleasing” and “charming” effects of metric irregularities in performance. For example, commentary in Campbell and Sharp (1917) on their transcription of Appalachian ballad performances from the early twentieth century suggests that, in addition to adding interest to strophic songs, disrupting metric regularity seems to be an essential component of the “magical” impact of these song performances; see Campbell and Sharp (1917, x). They position him as a narrator whose storytelling impulses and understanding of text emphasis allow him to control the pace of lyrical delivery. These features—alongside Guthrie’s other techniques of narrative, rhetoric, and metric disruption—are part of the lasting impact of his influence on American popular music.

The Anthology of American Folk Music: Another source for performed-out fermatas

Guthrie’s use of performed-out fermatas offers evidence of how this technique likely impacted Dylan’s early songwriting. Another possible source for Dylan is Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music, which was released as a three-volume set of recordings from Smith’s own collection of 78 rpm records (commercially released between 1929 and 1934). For more on Smith’s collection, see Marcus (1997). The Anthology represented advancements both musically and socially: it took advantage of the relatively new 33 1/3 rpm 12” disc LP medium, and it positioned previously segregated artists alongside each other on long-play records. As Neal explains, in the early twentieth century, musicians were catalogued not by musical style but rather by race: “hillbilly records” included recordings by white musicians and “race records” by Black artists (2002, xiii). By 1952, the latter had become “Rhythm and Blues” and the former “Country and Western” (Rosenberg 1997, 36). The Anthology has been retroactively described as a central, “founding document” (Marcus 1997, 5) of the American folk music revival, with 1960s artists like Dylan, Joan Baez, Dave Van Ronk, and Buffy Sainte-Marie recording their own versions of Anthology songs. Some examples of these recordings in the 1960s include Dylan’s version of “See That My Grave Is Kept Clean” (Blind Lemon Jefferson) on his eponymous 1962 debut album, Sainte-Marie’s version of “House Carpenter” on Little Wheel Spin and Spin (1966), Van Ronk’s “House Carpenter” on Inside Dave Van Ronk (1964), and Joan Baez’s version of “The Wagoner’s Lad” on Joan Baez, Vol. 2 (1961). For commentary on the influence of the Anthology being retroactively overstated, see Hair and Smith (1997).

Kazee, “The Butcher’s Boy” (1925)*

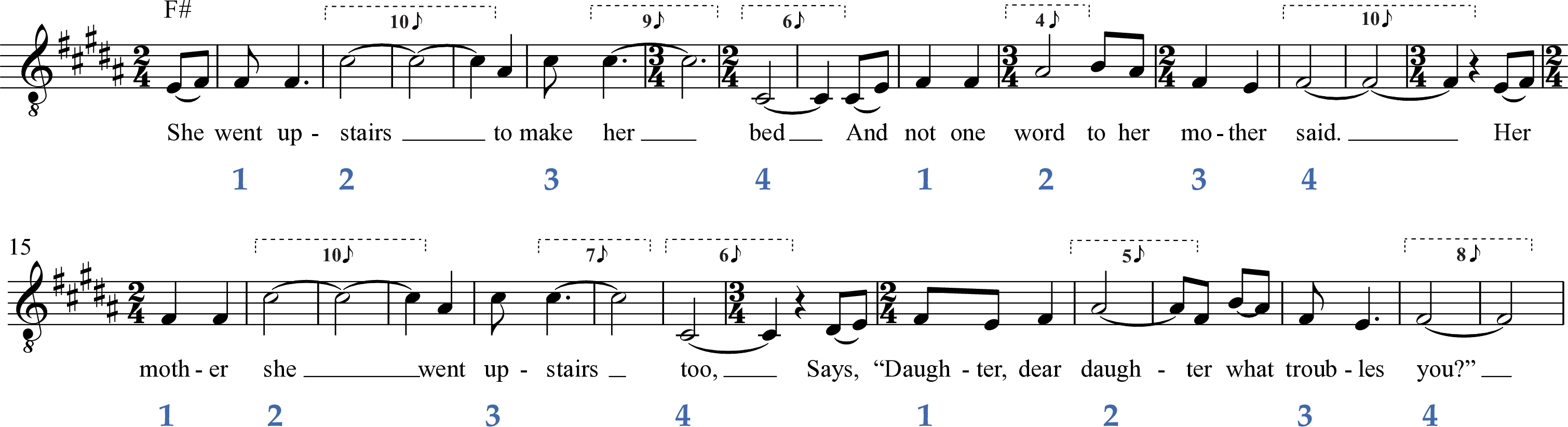

Several tracks from the Anthology—particularly on the “Ballads” and “Social Music” volumes—demonstrate several different uses of the performed-out fermata technique. On the “Ballads” volume, Smith includes two tracks by the Kentucky-born country-folk singer Buell Kazee. Kazee’s version of “The Butcher’s Boy” shows a similar approach to the long-held notes that Guthrie employed. The lyrics involve tragic subject matter, with Kazee singing from the perspective of a young woman who hangs herself after an unrequited romance with a “railroad boy.” The text has an underlying pattern of four accented syllables per line (“She went up-stairs to make her bed”) that Kazee expands beyond a prototypical four-bar structure in his performance by holding out melody notes in specific locations. This song is also analyzed by Tobias Tschiedl (2020), who tracks the varying time spans between stressed syllables of Kazee’s performance. Several recordings of “The Butcher’s Boy” predate Kazee’s Anthology version. Two available versions have entirely regular metric settings and place their first hyperdownbeats on the second stressed word. Henry Whitter’s 1925 recording also features a four-beat text structure (i.e., “In John-son cit-y where I did dwell”) with a weak–strong hypermetric setting. Kelly Harrell’s 1925 version, four stressed syllables span each two-bar unit of triple meter. The first and third stresses align with beat 3 while the second and fourth stressed words receive downbeat emphasis (i.e., “In Lon-don cit-y where I did dwell / The butch-er’s boy I lov-ed so well”). Either of these recordings may have influenced Kazee’s underlying four-beat structure—with metric emphasis on the second beat—though, neither recording contains performed-out fermatas. Many thanks to one of the anonymous reviewers for recommending these two recordings. Seeger (1972, 50) includes a transcription of Woody Guthrie’s 1954 cut-time version of this song, which emphasizes the same syllables as the 1925 recordings (“In Jer-sey Cit-y where I did dwell”) and places hyperdownbeats on the second stress of each line.

In the first hypermetric unit (Example 5), Kazee holds the C♯4 on “stairs” for ten eighth-note beats, when the duration could have been a single quarter-note beat (such that “stairs” and “to” would have been part of the same bar). This transcription follows the metric and hypermetric structure shown in Raim (1973, 28). Kazee includes nearly identical performed-out fermatas—in both location and length—in the first stanza of his 1958 recording on Buell Kazee Sings and Plays. Unlike in Guthrie’s songs, Kazee does not provide a melodic prototype in “The Butcher’s Boy” to which his performed-out fermatas can be compared. For this transcription and those that follow, I only include brackets and lengths of the long-held melody notes with the possible prototype rhythms implied as whatever duration would fill a single measure with the pitch that follows the held note. For example, in the first instance of performed-out fermata, the C♯4 could have been a quarter note within a possible second bar with the A♯4 that follows. Subsequent long-held melody notes expand the unit further from a prototype of four bars (shown with numbers below the staff) to an actual length of eight bars, with an extra beat added in the sixth bar. In this transcription, I suggest that “went” aligns with a hyperdownbeat. It is also possible to hear “stairs” as the beginning of the hypermeasure, with “She went up” as a large anacrusis. This possibility would shift each hyperdownbeat in Example 5 one bar later. Each of his performed-out fermatas lands on strong hyperbeats; in addition to increasing interest in his strophic song performance, these long-held notes also help orient the meter through durational accents. I thank one of the anonymous reviewers for this observation.

Similar performed-out fermata techniques occur in the next few vocal lines, always extending the second and fourth stressed syllable but only sometimes extending the third. Yet Kazee rarely holds his vocal fermatas for precisely the same duration. There are, therefore, layers of duality here: the tension provoked by performed-out fermatas projecting both a cessation, and continuance. Forward momentum is further compounded by Kazee’s placement of deploying the technique in predictable locations but using unpredictable durations. This increased tension and unpredictability helps to reflect the lyrics: unrequited love, heartbreak unhealed, and the daughter’s decision to take her own life.

Kazee, "The Wagoner's Lad"

Kazee’s other song in the Anthology, “The Wagoner’s Lad,” demonstrates some new extension techniques for performed-out fermatas in strophic song performance. The song is introduced in the Anthology liner notes as a “folk-lyric” song, a quasi-balled in which love is denied or betrayed, with the description “Local girl’s protest that whip needs fixing fails to halt wagoning boy friend’s departure” (Smith 1997, 3). White classifies the song as “Folk Lyric” with a narrative “of unhappy love that [is] of uncertain content, taking up or sloughing off phrases and images as they pass through the minds and feelings of singers” (1952a, 275–279). The transcriptions in White (1952b, 157–162) show fermatas in the melody: in some locations they appear on the first note, in others on a mid-phrase pitch, typically a high note. Version B(a) also includes time signature changes. These versions, from 1936–1941, retain the metric play of Kazee’s 1928 version. Version H has no fermatas (save for the final note) or metric irregularities. In this song, the long-held notes appear in the middle of a phrase, as they do in “The Butcher’s Boy.” This is shown in the second and third systems of Example 6, where the D4 pitch is held for a whole-note duration that extends a possible four-bar unit to five bars.

Kazee also uses performed-out fermatas to create extended anacruses at the beginnings of his phrases. The first such instance occurs in on the very first note he sings (shown in Example 6), where the anacrusis event (which could have been a short duration like an eighth or quarter note) is extended to a total duration of nine eighth-note beats across two different pitches. He displays a similar technique in the final line of Example 6, in which an anacrusis event lasts for nine eighth-note beats before arriving on the downbeat with the word “been.”

The mid-phrase performed-out fermatas in “Wagoner’s Lad” suspend time to delay the arrival of the third hyperbeat of the phrase. In contrast, the anacrusis type of long-held notes suspends time before the vocal phrase begins, increasing the anticipation for the first downbeat by delaying it. Campbell and Sharp’s (1917, 216) Version B of this song, transcribed in 1908, includes an anacrusis to each of the stanza’s four lines and has a similar melodic contour to Kazee’s version. Since this version was recorded in Clay County, Kentucky, about 100 miles from Morehead, KY, where Kazee lived, it is possible that the elongated version was part of an oral tradition that influenced Kazee’s own performance . This also postpones resolution of the non-chord tone, A, held here in dissonance against the banjo’s G-major tonic harmony. In addition to adding variety to his strophic song performances, these performed-out fermata techniques are rhetorical devices for Kazee to control how the song’s narrative is delivered. Neal finds examples of vocal fermata in country music to be techniques of expression, what she calls “structural reinforcement” of a singer’s “emotional resignation or regret, and potential lost love” (2000, 122).

Performed-out fermatas and elongated harmonic zones

The Carter Family, “Engine 143” (1929)*

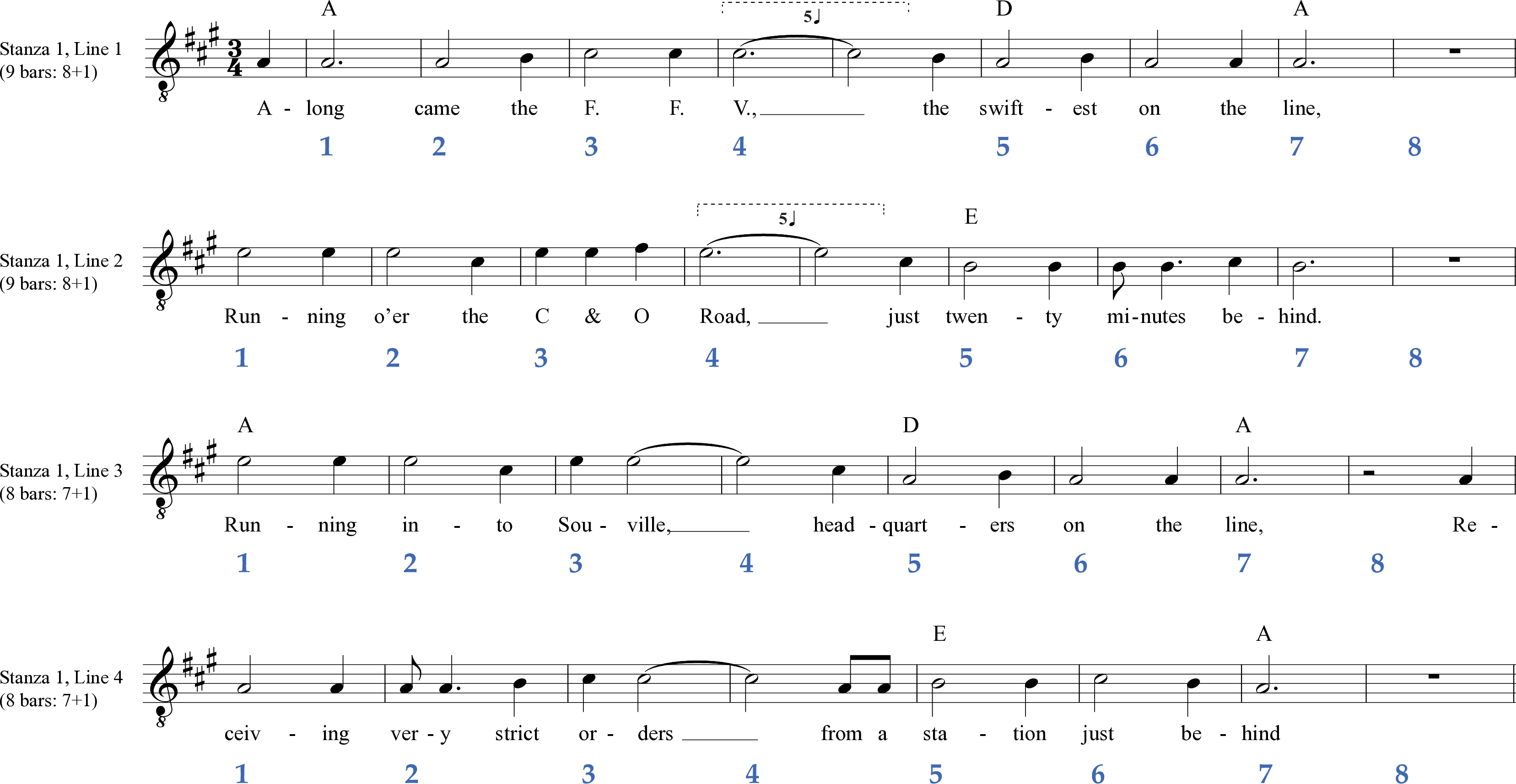

The sense of anticipation created by performed-out fermatas in Kazee’s songs is driven by his insistent banjo accompaniment occurring beneath the metric expectations of his melody. In other Anthology songs, the technique of long-held notes can also interact with expectations for harmonic rhythm and the length of time spent on each harmony. In “Engine 143” by the Carter Family (Example 7) It is also possible to hear the lyrics in stanza 1, line 4 as “receiving their strict orders.” , elongated melody notes result in harmonic zones lasting longer than expected and delaying a subsequent harmony. The lyrics describe the wreck of the Fast Flying Virginian (FFV), a passenger train on the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway in West Virginia that struck a rockslide on October 23, 1890, killing the train’s engineer. Norm Cohen explores the history of this song, recorded both as “Engine 143” and “The Wreck on the C & O.” Cohen cites factual issues in the circulated lyrics for more than 70 versions of the song, proposes that its original composer was “raised in the Anglo-American broadside ballad tradition,” and assumes that it was written several years after the train wreck occurred, “when some of the details had been forgotten or become confused in the author’s mind” (1981, 183–196). Of the Carter Family’s version, Cohen suggests that Sara Carter learned the song as a teenager, “probably less than twenty years after the incident,” and the text she provided for the Carter Family version is “considerably truncated and stripped of details” (1981, 194).

In the first two vocal lines, mid-phrase performed-out fermatas (lasting for five quarter-note beats) extend the first half of the phrase to result in an additional bar. Instead of a four-bar unit of tonic harmony, the performance includes five bars, delaying the arrival of the fifth downbeat and the subdominant harmony. In other words, the performed-out fermata results in what I call an elongated harmonic zone. (This technique also occurred in Guthrie’s “Pretty Boy Floyd;” see Example 3.)

In the first two stanza lines of “Engine 143,” this has an ironic meaning: the F. F. V. is apparently the “swiftest” train on the line and yet is “just twenty minutes behind.” When the train receives “strict orders” from headquarters, the vocal phrases tighten up to normative eight-bar units. These lines also show what the first two phrases would sound like without the fermatas: in lines 3 and 4 there is still a long-held melody note, but this one creates hypermetric and harmonic regularity, rather than disrupting it, since it occurs in the third bar rather than the fourth. Here, there is enough space to hold a long duration in the melody followed by a pick-up to the fifth downbeat on subdominant harmony. In the first and second lines, because the long-held note occurs “too late” (in the fourth instead of the third measure), an extra bar is added before the pick-up to the subdominant.

In subsequent stanzas, performed-out fermatas occur in similar locations within the melody line but not always in the same pattern between the lines. As shown in Example 8, long-held melody notes occur in three lines in stanzas 2 and 3 (lines 1, 3, and 4 in the former and 2, 3, and 4 in the latter) and in the final two lines of stanzas 4 and 5. In some of these lines, the technique seems to arise to give intentional emphasis to certain words (like “life” and “blood”) and emphasize stressed syllable patterns in the lyrics. The rhythm of the text might have been a determining factor for where the performed-out fermatas would occur. The unexpanded phrases (lines 3 and 4) have only three stressed syllables for each line segment: “Run-ning in to Sou-ville” and “head-quart-ers on the line” in line 3 and “Re-ceiv-ing ver-y strict or-ders” and “from a sta-tion just be-hind” in line 3. The phrases expanded by performed-out fermatas (like lines 1 and 2), have four syllables with an extra bar after the fourth. (Line 1, for example has “A-long came the F. F. V. [extra bar]” and “the swift-est on the line [extra bar]). This pattern continues throughout the song, with three-stress line segments set to four bars and four-line segments including an extra fifth bar. Many thanks to one of the anonymous reviewers of this article for pointing out this text-stress pattern and its possible impact on the Carter Family performance. But its overall impact is as a rhetorical technique in the Carter Family’s metric style, arising when Sara Carter decides to hold a melody note slightly longer, adding variety and drama to the performance of this train-wreck narrative.

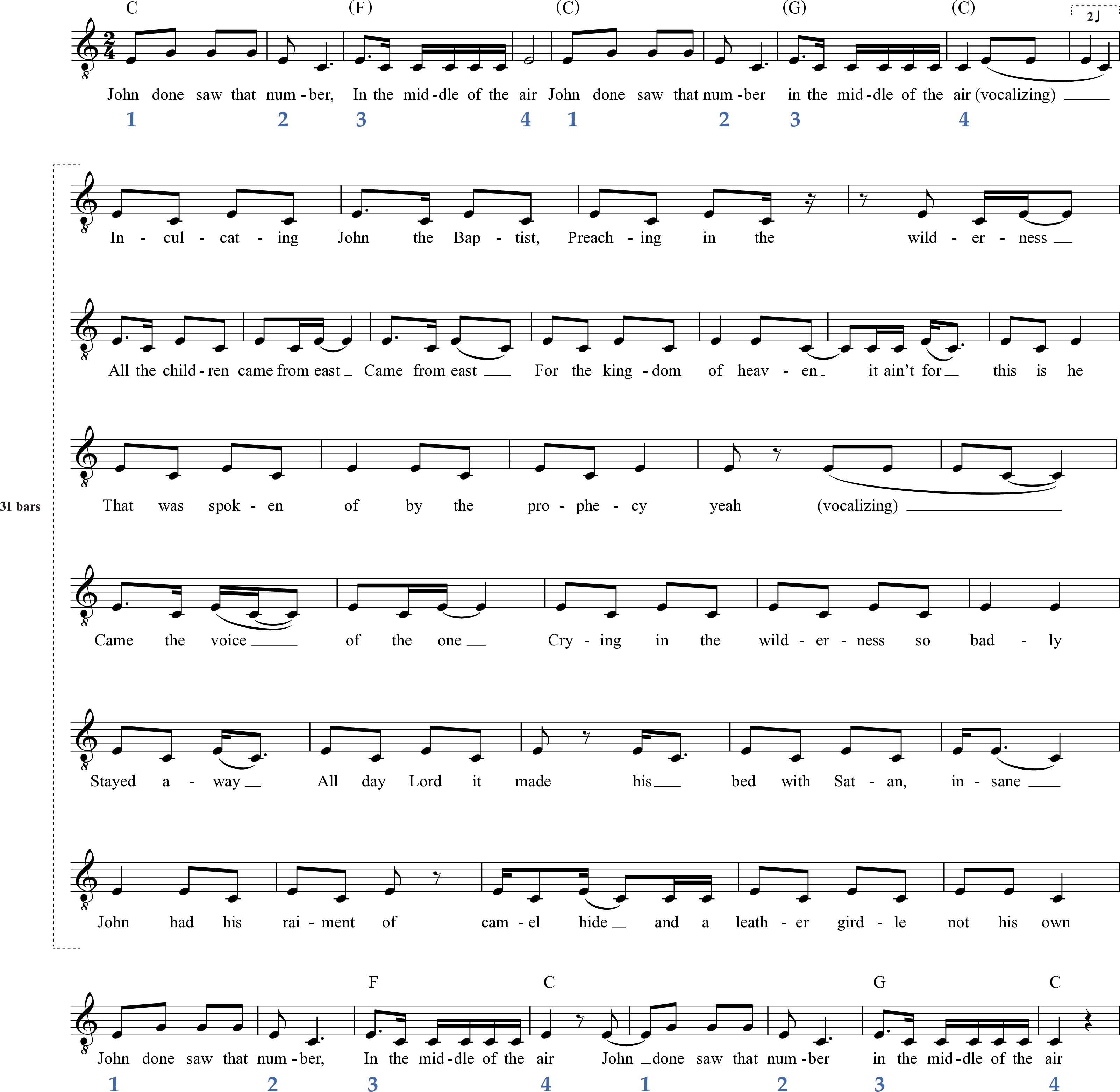

Rev. Moses Mason, “John the Baptist” (1928)

In the same way that performed-out fermatas lengthen an actual or imagined prototype phrase by pausing on a particular pitch, elongated harmonic zones pause on a certain harmony to lengthen a potential prototype structure. This technique of elongated harmonic zones found in “Engine 143” is taken to an extreme on a track from the “Social Music” volume of Harry Smith’s Anthology: Rev. Moses Mason’s “John the Baptist.” Mason begins the song with a hypermetrically regular introduction, shown in the first system of Example 9, with a one-bar extension before his first verse. In later iterations of this refrain, he includes harmony changes at the moments I have indicated in parentheses above the staff, but these are not present on first listening. The metric irregularity of his verse contrasts with the regularity of the refrain: the sustained harmony of verse 1—which prolongs C major for thirty-one bars before releasing to the refrain again—eventually gives way to the refrain’s changing and more regular harmonic rhythm. On first listening, the shift to the refrain is almost imperceptible because there is no change of harmony at “John done saw that number.”

In the initial measures of this verse section, expectation for harmonic motion—expectations that were already low, given the harmonic stasis of the first refrain—must be abandoned. The vocal style in the elongated C major harmonic zone evokes the rhetoric of a loquacious preacher. And indeed, Mason’s harmonic elongation in “John the Baptist” arises from the “guitar evangelist” style of his performance, which alternates between a harmonically static verse and a communal refrain on a religious topic. Another example of this style can be found on the “Social Music” Anthology volume, with Blind Willie Johnson’s self-accompanied performance on “John the Revelator” with singer Angeline Johnson. Blind Willie Johnson is also described in the Anthology liner notes as a “guitar evangelist” (Place 1997, 54). Mason’s other songs in this style also showcase his characteristic elongation of harmonic zones, some of which are intensified by an unaccompanied texture in which repeating melodic gestures create both harmonic stasis and repetition to underscore the rhetoric of his oration. Mason uses a similar technique on his 1928 performance of “Judgement Day in the Morning.” This and other recordings from his guitar evangelist style can be found on Alabama: Black Secular & Religious Music (1927–1934) (1993).

Bob Dylan and the performed-out fermata

The metric style of Guthrie’s music as well as songs from Smith’s Anthology have similarities to long-held notes in the 1960s folk revival. In my studies of Bob Dylan’s use of meter for self-expression, I see instances of performed-out fermatas used in similar ways to the examples explored earlier: Dylan’s 1960s songs also use these techniques as mid-phrase expansions, to lengthen anacrusis functions, and to elongate harmonic zones. In addition to the two songs explored in this study, Dylan’s “Freight Train Blues” (1962) also features a performed-out fermata on the word “blues” (1:11–1:25), with the vowel sound resembling a train whistle.

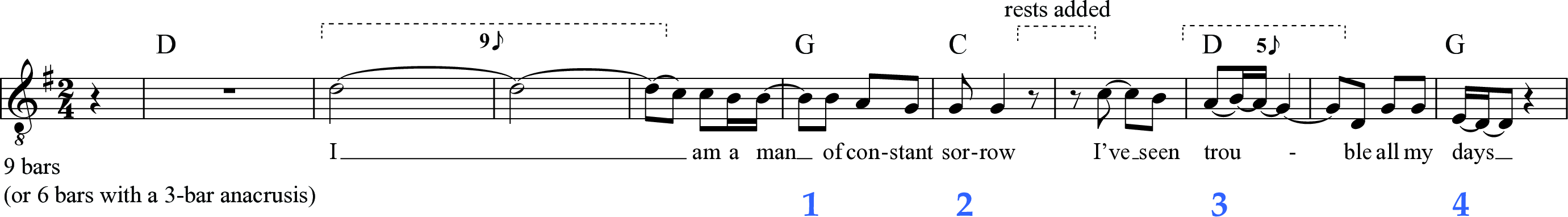

Bob Dylan, "Man of Constant Sorrow"

Dylan’s recording of the traditional song “Man of Constant Sorrow” was included on his eponymous 1962 album. His version is likely based on the 1950 recording by The Stanley Brothers and on versions circulating the 1960s coffeehouse scene by artists like Joan Baez. Harvey (2001) traces many of Dylan’s early 1960s songs to plausible sources, including to Guthrie and tracks on Smith’s Anthology. Dylan’s version includes some changes to the lyrics but retains the general storyline of the narrator leaving his past, regretting a lost love, and contemplating his future and death. For more on “Man of Constant Sorrow,” see Harvey (2007; 2001, 65–67).

The first vocal line of Dylan’s performance (Example 10) illustrates several types of performed-out fermata techniques that yield a nine-bar vocal line with an underlying four-bar hypermeter, encouraged by possible text stresses on “man,” the first syllables of “sorrow” and “trouble,” and the final word “days.” Dylan’s long-held note on the initial pitch extends the pronoun “I,” delaying both the first downbeat and the reveal of the narrator’s identity. The phrase gets additional length from two further techniques that elongate harmonic zones: added rests after “sorrow” (that delay the return to dominant harmony) and a mid-phrase performed-out fermata (with a melisma) on the first syllable of “trouble,” which delays the arrival of tonic harmony by one bar. In adding these performed-out fermata techniques to his first phrase, Dylan, like the other artists in this study, controls the rhetoric of the song’s narrative—expressively pausing at “I” as if the sense of self reflected in this moment has a “troubled” past and uncertain future that necessitate a moment of consideration before proceeding to the rest of the song.

Bob Dylan, "I Shall Be Free No. 10"

In Dylan’s talking-blues-inspired song “I Shall Be Free No. 10” (from his 1964 album Another Side of Bob Dylan), he includes an extended harmonic zone that evokes similar metric rhetoric to Mason’s recording. Dylan is indebted to Guthrie for inspiration in the talking blues style, as explored in Harvey 2001 (102–105). Harvey (50–52) cites the 1944 “Guthrie et al. recording of ‘We Shall Be Free’” as the “immediate source” for Dylan’s “I Shall Be Free” from The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. Dylan’s first phrase (Example 11) posits an underlying four-bar unit, which is extended by two measures before the tonic harmony returns at the word “Fee.” The second phrase reinforces a similar structure, though it, too, is extended by one bar. The “expected” structure dissolves by the third vocal phrase where Dylan adds beats, seemingly at random, that extend harmonic zones. His tonic harmony lasts an additional quarter-note beat, necessitating a change to 3/4 for this bar. The subsequent subdominant harmonic zone lasts three quarter-note beats longer than the prototypical single bar of the previous two phrases. During the harmonic zone on the dominant, Dylan repeats text on the harmony to extend it to twelve bars. The possibility for a “typical” unit length quickly dissolves. By the time Dylan reaches the counting lyrics (“Ninety-nine, a hundred, a hundred and one, a hundred and two”), there is a comedic sensation to his control of time. This metric play holds the listener’s attention as the lyrics humorously proceed through different types of counting in boxing, delaying resolution to the tonic for a significantly longer passage than the smaller extensions of the previous phrases. This metric humor is one of many instances of Dylan manipulating meter and timing for expressive purposes, expanding on similar stylistic irregularities to those found in Guthrie’s music and on the Anthology. In “I Shall Be Free No. 10,” it is used for humor; elsewhere in Dylan’s early catalogue, there are connections to more serious lyrical themes, which come to be a feature of his politically charged 1960s songwriting. For example, Murphy (2020) explores the impact of timing flexibilities in “With God on Our Side,” which reflect both the political lyrical theme of the song and the broader unpredictability of Dylan’s early performance style.

Conclusion

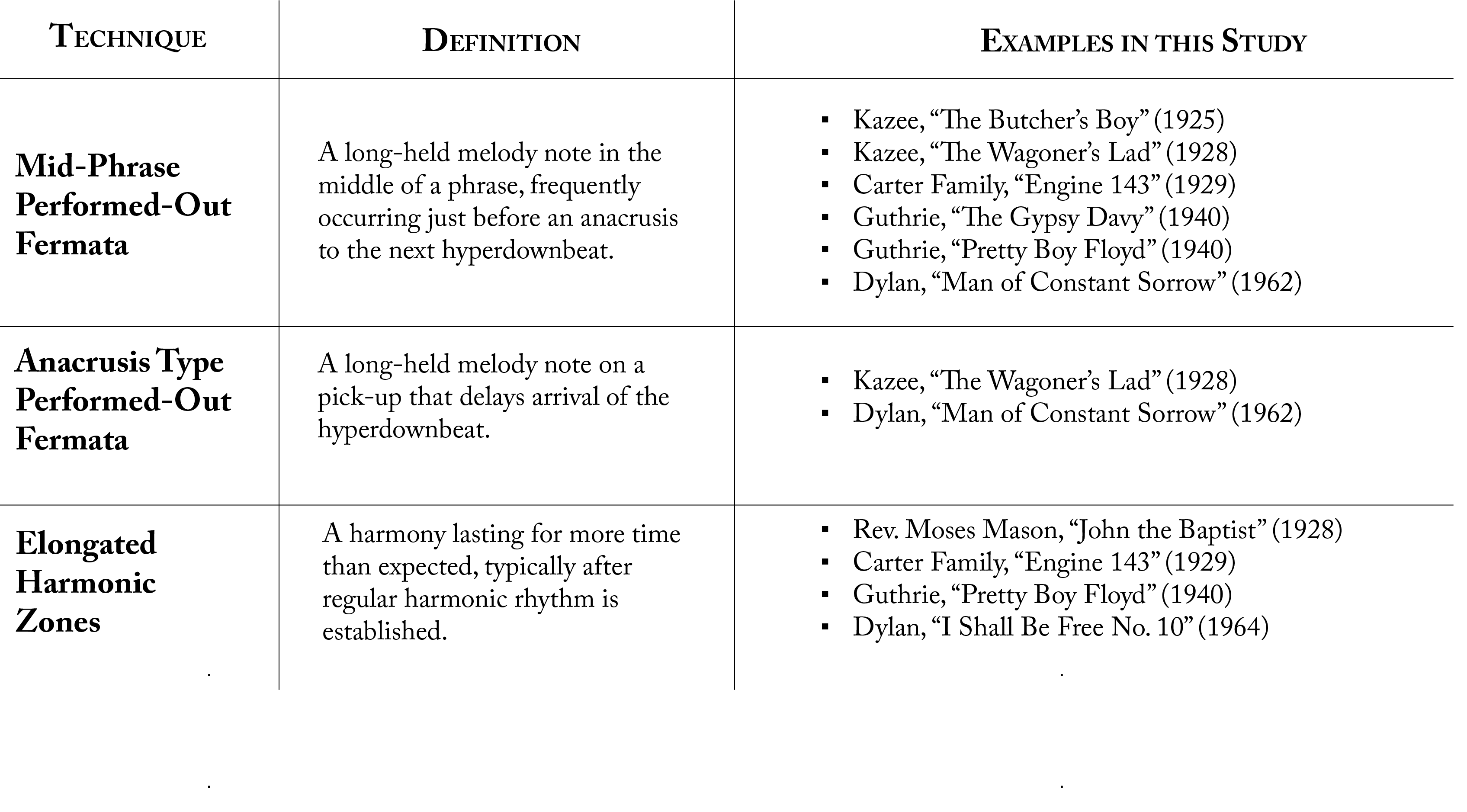

This short study of performed-out fermatas has uncovered three related techniques that are summarized in [Table 1](table_1): (1) long-held notes that occur in the middle of the phrase, (2) melodic extensions of anacrusis function, and (3) elongations of harmonic zones—either resulting from mid-phrase long-held melody notes or from the repetition of content over an unexpectedly prolonged harmony. Songs in Table 1 are in chronological order. Some songs demonstrate multiple techniques in a single performance. For example, “Engine 143” and “Pretty Boy Floyd” display mid-phrase performed-out fermatas that also serve to elongate harmonic zones. In the former, this is because there is a clear harmonic progression in the Carter Family version of this song, and a long-held melody note extends the subdominant harmony and delays the arrival of the dominant by one bar. In the latter, the performed-out fermata delays the arrival of the subdominant. Kazee’s songs, by contrast, are only included in one category because they demonstrate mid-phrase performed out fermatas and not elongated harmonic zones, since his performances feature a static harmony with melodic motives articulated in the banjo that do not create regular harmonic progressions. Dylan’s “Man of Constant Sorrow” includes both anacrusis-type and mid-phrase performed-out fermatas in the first line. The three performed-out fermata types differ in position and metric function but are related by their demonstration of simultaneous motion and stasis.

Throughout this article, I have positioned performed-out fermatas as a technique that occurs to add interest to strophic song performances, creating a quirky metric rhetoric in folk revival sources that found its way into 1960s songwriting. I have examined a limited number of songs here, but there is much more to be explored in the rich metric rhetoric of folk revival sources and the broader rhetorical connections between this repertoire and 1960s singer-songwriter music.

Works Cited

Benjamin, William E. 1984. “A Theory of Musical Meter.” Music Perception 1 (4): 355–413.

Berry, Wallace. 1987. Structural Functions in Music. New York: Dover.

Campbell, Olive Dame, and Cecil James Sharp. 1917. English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians: Comprising 122 Songs and Ballads, and 323 Tunes. New York: Putnam and Sons.

Child, Francis James. 1882. English and Scottish Popular Ballads, Part VII. Edited by Helen Child Sargent and George Lyman Kittredge. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co.

Cohen, Norm. 1981. Long Steel Rail: The Railroad in American Folksong. Edited by David Cohen. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Hair, Ross, and Thomas Ruys Smith. 1997. Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music: America Changed Through Music. New York: Routledge.

Harvey, Todd. 2001. The Formative Dylan: Transmission and Stylistic Influences. Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, Inc.

Harvey, Todd. 2007. “Never Quite Sung in This Fashion before: Bob Dylan’s ‘Man of Constant Sorrow.’” Oral Tradition 22 (1): 99–111.

Heylin, Clinton. 2011. Behind the Shades: The 20th Anniversary Edition. London: Faber and Faber.

Marcus, Greil. 1997. “The Old, Weird America.” In A Booklet of Essays, Appreciations, and Annotations Pertaining to the Anthology of American Folk Music, edited by Harry Smith. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Murphy, Nancy. 2020. “Expressive Timing in Bob Dylan’s ‘With God on Our Side.’” Music Analysis 39 (iii): 389–413.

Murphy, Nancy. 2023. Times A-Changin’: Flexible Meter as Self-Expression in Singer-Songwriter Music. New York: Oxford University Press.

Neal, Jocelyn. 2000. “Songwriter’s Signature, Artist’s Imprint: The Metric Structure of a Country Song.” In Country Music Annual, edited by Charles K. Wolfe and Hames E. Akenson, 112–140. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2000.

Neal, Jocelyn. 2002. “Song Structure Determinants: Poetic Narrative, Phrase Structure, and Hypermeter in the Music of Jimmie Rodgers.” PhD diss, Eastman School of Music.

Place, Jeff. 1997. “Supplemental Notes on the Selections.” In A Booklet of Essays, Appreciations, and Annotations Pertaining to the Anthology of American Folk Music, edited by Harry Smith. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Raim, Ethel. 1973. Anthology of American Folk Music. Edited by Josh Dunson, Moses Asch, and Ethel Raim. New York: Oak Publications.

Reuss, Richard A. 1970. “Woody Guthrie and His Folk Tradition.” The Journal of American Folklore 83 (329): 273–303.

Rings, Steven. 2013. “A Foreign Sound to Your Ear: Bob Dylan Performs ‘It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding).’” Music Theory Online 19 (4).

Rockwell, Joti. 2011. “Time on the Crooked Road: Isochrony, Meter, and Disruption in Old-Time Country and Bluegrass Music.” Ethnomusicology 55 (1): 55–76.

Rosenberg, Neil. 1997. “Notes on Harry Smith’s Anthology.” In A Booklet of Essays, Appreciations, and Annotations Pertaining to the Anthology of American Folk Music, edited by Harry Smith. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Seeger, Pete. 1960. “An Introductory Note About the Man and His Music.” In California to the New York Island: Being a Pocketfull of Brags, Blues, Bad-Men Ballads, Love Songs, Okie Laments and Children’s Catcalls by Woody Guthrie, 3–4. New York: Oak Publications: The Guthrie Children’s Trust Fund.

Seeger, Pete. 1972. The Incompleat Folksinger. Edited by Jo Metcalf Schwartz. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Smith, Harry, ed. 1997. Anthology of American Folk Music Liner Notes. CD reissue. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Tschiedl, Tobias. 2020. “Improvised Metric Flexibility in Early Recordings of Self-Accompanied ‘Hillbilly Songs’: Clarence Ashley’s ‘The House Carpenter’ (1930) and Buell Kazee’s ‘The Butcher’s Boy’ (1928).” Paper presented at the South Central Society for Music Theory Conference, Nashville, TN.

White, Newman Ivey, ed. 1952a. The Frank C. Brown Collection of North Carolina Folklore. Vol. 3. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

White, Newman Ivey, ed. 1952b. The Frank C. Brown Collection of North Carolina Folklore. Vol. 5. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Zak, Albin J. 2004. “Bob Dylan and Jimi Hendrix: Juxtaposition and Transformation ‘All Along the Watchtower.’” Journal of the American Musicological Society 57 (3): 599–644.

Baez, Joan. 1961. Joan Baez, Vol. 2. Vanguard VRS 9094.

Dylan, Bob. 1964. Another Side of Bob Dylan. Columbia CS 8993.

Dylan, Bob. 1962. Bob Dylan. Columbia CS 8579.

Dylan, Bob. 1963. Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. Columbia CS 8786.

Guthrie, Woody. 1940. Dust Bowl Ballads. Victor P 27.

Harrell, Kelly. 1925. “The Butcher Boy”/"I Wish I Was a Single Girl Again". Shellac, 10" 78 RPM. Victor 19563.

Kazee, Buell. 1958. Buell Kazee Sings and Plays. Folkways Records FS 3810.

Sainte-Marie, Buffy. 1966. Little Wheel Spin and Spin. Vanguard VRS 9211.

Smith, Harry, ed. 1997. Anthology of American Folk Music. CD reissue. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Van Ronk, Dave. 1964. Inside Dave Van Ronk. Prestige Folklore FLST 14025.

Various. 1993. Alabama: Black Secular & Religious Music (1927–1934). Document Records DOCD-5165.

Various. 1942. Anglo-American Ballads, Volume One. Library of Congress AFS L1.

Whitter, Henry. 1925. “I Wish I Was a Single Girl Again”/"The Butcher Boy". Shellac, 10" 78 RPM. Okeh 40375.