We are grateful for the work of our research assistants Mira Perusich, Jonas Kastenhuber, Alexis Cantelme, and Monserrat Torres Guillen, as well as for the feedback of Trevor de Clercq and the anonymous peer reviewers. Fans often discuss the “feels” of popular music drummers, making claims about the particular features that characterize their sound. The drumming of Charlie Watts of the Rolling Stones has especially been the subject of intense debate. When Watts died in August 2021, a headline in The Times of London proclaimed that his drumming “would make drum machines weep” (Hepworth 2021), with the majority of commentators describing his playing as “behind the beat.” For example, Bruce Springsteen’s drummer Max Weinberg wrote: “Charlie became a proponent—as I am—of a style of rock drumming popularised by the late, great Al Jackson, the famous Stax drummer, where you deliberately play behind the direct backbeat” (Beaumont-Thomas 2021). Others have made a different assessment, with podcast host and drummer Monte Mallin claiming in 2012 that it was Watts being “slightly ahead of the beat” that gave the band its characteristic rhythmic feel. MrMonte (Monte Mallin), reply to “Musicians: How Do You Explain Charlie’s Technique to Drummers?,” It’s Only Rock’n Roll forum, March 9, 2012, https://iorr.org/talk/read.php?1,1579013,page=1. Discussions of Watts’s approach to tempo variability have also differed, with some claiming he is “metronomic” while others asserting that the band’s tempo ebbed and flowed. Bassist Darryl Jones, who has played with the band for thirty years, said of Watts: “He has a way of being very, very steady without being metronome-like . . . there should be some breathing, you know, and he’s great at that” (Ward 2018, 2:29–3:04).

In order to investigate these claims, we engaged in an empirical study focused on microtiming and tempo variability in the drumming of Watts with the Rolling Stones. Besides its value for close musical analysis, our study examines value judgments connected to popular music: descriptions praising Watts’s style of playing as “human,” “natural,” or “organic” seem informed by an ideology of authenticity, while other drummers or sequencers are described negatively as “mechanical,” “lifeless,” “cold,” or “robotic.” Different ways of dealing with rhythm are thus connected to larger philosophies and ways of seeing the world.

In what follows, we first review prior scholarship on microtiming in popular music drumming. We then explain the methodology we developed for analyzing microtiming in the drumming of Charlie Watts. Our third section discusses the results of our microtiming study, revealing the extent to which Watts delayed backbeats in comparison with other drummers. We then turn to tempo variability, identifying common tempo curves in Rolling Stones songs. We present our method of measuring tempo variability with a single number (the coefficient of variation) and apply it to corpora of Rolling Stones songs and songs by other artists, showing trends over time. Finally, we review our findings and discuss how they connect with larger questions of genre and authenticity in popular music.

I. Prior Scholarship on Microtiming in Popular Music Drumming

In 1987, Charles Keil referred to microtiming deviations as “participatory discrepancies” (or “PDs”), which he argued were essential elements of groove in jazz and other popular genres (275, 277). Studies of swing ratios in jazz eventually inspired scholarly interest in microscopically delayed backbeats in rock, with Iyer contending that playing the snare slightly behind the backbeat is a crucial component of African American music and the music it has inspired, contributing to a “relaxed” and “laid back” feel (2002, 406; see also Butterfield 2006, 33, 39–41). Drummers instructed to play in a “laid-back” manner with a click track at a moderate tempo of 96 BPM delayed snare attacks by 17.4 ms on average (Danielsen et al. 2015, 2306; see also similar findings by Câmara et al. 2020, 11).

Other scholarship has attempted to empirically measure listeners’ ability to detect such microrhythmic deviations. The just noticeable difference (JND) for timing discrepancies found by Friberg and Sundberg was 2.5 percent of the beat length for tempos between 60 and 200 BPM, meaning that discrepancies of this size or larger were perceptible (1995, 2528). Madison and Merker found that the JND for timing discrepancies was 2.5 percent for listeners with musical training and 4.4 percent for those without (2002, 204). But Madison and Merker have also shown that musicians can subliminally respond to deviations as small as 1.5 ms at tempos between 92 and 100 BPM, even though deviations that small are not consciously recognizable (2004, 71).

Scholars have also sought to determine the extent to which deviations such as playing behind the beat or altering swing ratios contribute to a sense of groove. Research shows that jazz listeners prefer music with timing discrepancies but also prefer that these discrepancies be relatively small (Hofmann et al. 2017, 339). Similar research suggests that systematic microtiming deviations in jazz are crucial to creating a sense of swing (Nelias et al. 2022, 6–7). Other scholars, however, have been unable to find empirical evidence that microtiming deviations contribute positively to a sense of groove or make the music more pleasurable (Senn et al. 2016, 11; Davies et al. 2012, 507; Madison et al. 2011, 1588). Senn et al., in their review of the extensive literature regarding the effects of microtiming deviations on groove, wrote that research to date had produced surprisingly few insights, though they allowed that exploration of other aspects of microtiming, such as the effect of different patterns of microtiming deviation and how microtiming changes over the course of a musical work, could potentially be fruitful (2017, 17–18). Subsequent research by Danielsen et al. (2019) emphasized that parameters like timbre, dynamics, and pitch play an important role in the perception of microtiming, and Senn (2023, 38) recently suggested that a failure to account for these additional parameters may be a reason why previous studies failed to find a relationship between microtiming and groove.

II. Microtiming Methodology Used in This Study

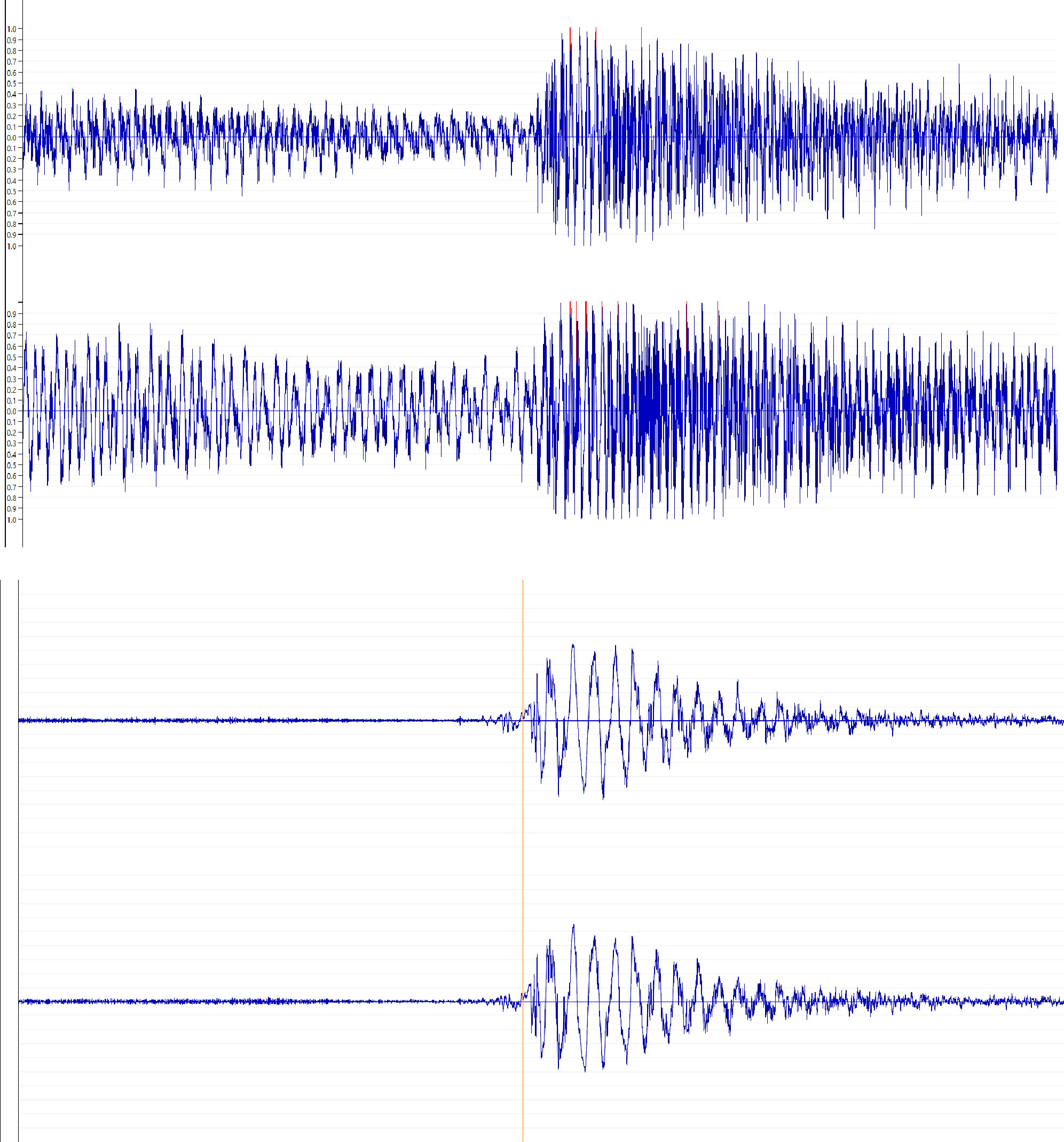

To measure microtiming in Watts’s drumming with the Rolling Stones, we used iZotope’s RX 9 or the Moises app to first separate the drums from the other instruments and vocals. See https://www.izotope.com/ and http://moises.ai. We initially used iZotope RX 9’s Music Rebalance tool to isolate the drums, but subsequently found that Moises could do the same job more efficiently, so we switched tools early in the study. Moises, built using a Python library called Spleeter, derives time-frequency masks using machine learning in order to perform source separation (Hennequin et al. 2020; Pang 2019). We then opened the isolated drum audio file in Sonic Visualiser and used the BBC Rhythm: Onsets plugin to automatically mark all quarter-note attacks (Example 1). See https://www.sonicvisualiser.org/ and https://www.vamp-plugins.org/download.html. In the BBC Rhythm: Onsets plugin, we used a Hann window shape, an FFT window size of 128 samples, and a window increment of 32. These settings allowed for a time resolution of 0.7 milliseconds. We started with a threshold setting of 3 and then increased or decreased it to automatically mark the quarter notes. In cases where the algorithm did not detect an attack that actually occurred, we lowered the threshold in a second layer and copied the resulting markers into the first layer. See Baume (2013) for a description of the plugin. Using this plugin resulted in markers that did not align with the visual onset of the attack in waveform view but typically appeared immediately after that initial onset. This approach accorded with where we heard the attack as well as with research showing that the perceptual center lies in between the physical onset and the high point of the attack (Danielsen et al. 2019, 403). Danielsen and others have discussed how there is not always a visual point in the representation of a waveform that will consistently align with human perception of the moment of attack—this is variable between instruments and versions of the same instrument (see also Hellmer and Madison 2015, 150). Identifying the moment of attack is easier with percussive attacks like drums, yet there is still no single timepoint that can be objectively identified. Identifying the moment of attack can also be complicated when there are near-simultaneous hits on multiple instruments within a drum kit (Hove et al. 2007; see also Câmara 2021, 35–41). The separation software we used did not allow for automatic separation of the hi-hats from the snare and kick; in the occasional instances when the onset detection plugin created two markers for a single beat, we analyzed only the broader-spectrum snare attack. Using automated attack marker placement allowed for the replicability of our results and for a more consistent and transparent method than annotating attacks by hand, even as we monitored the plugin’s markers to ensure consistency (see footnote 3).

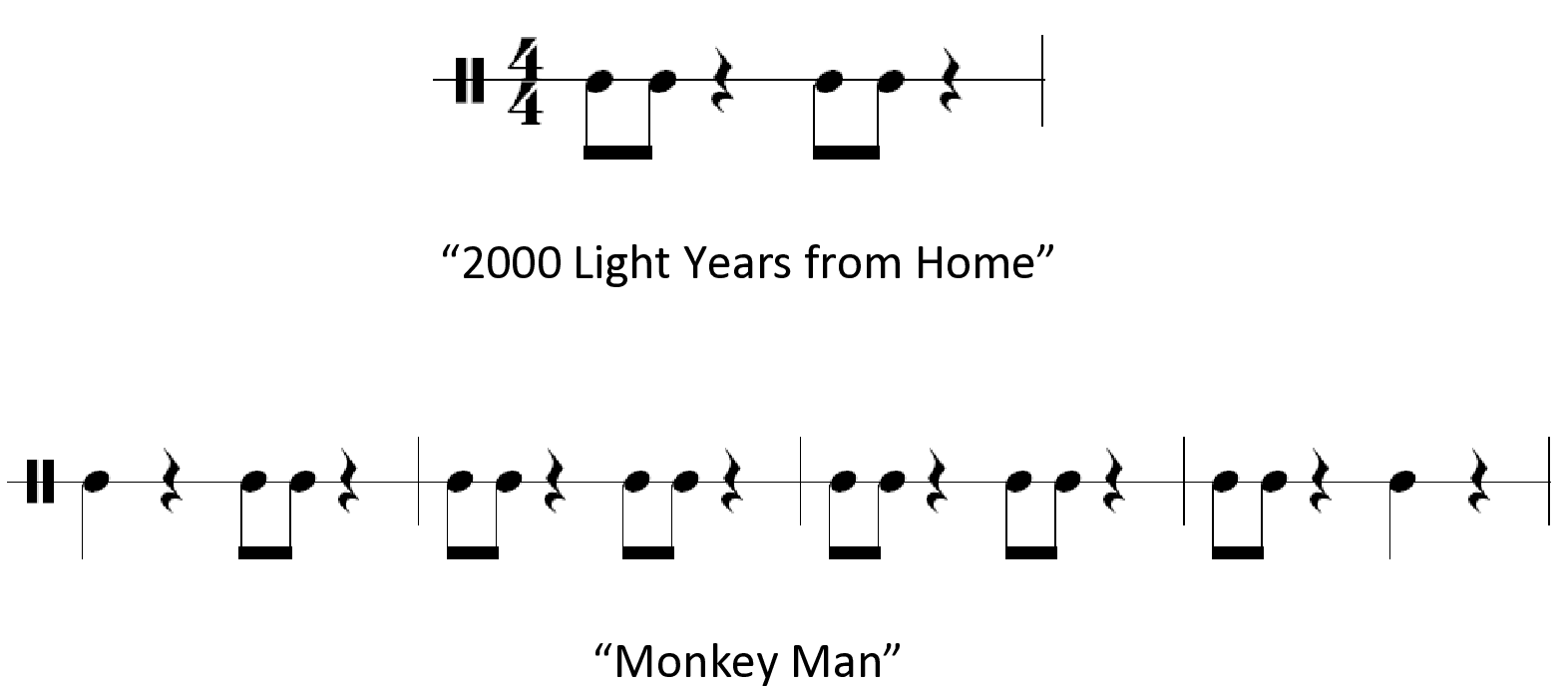

We focused entirely on quarter notes, in part to simplify a potentially overwhelming task, but also because of Watts’s drumming style and the nature of the discussion around it: the standard backbeat pattern—with kick drum on beats 1 and 3, snare on beats 2 and 4, and hi-hat on the eighth notes—was the primary pattern for Watts (as well as for rock music more generally). Eighth notes on the hi-hat are a fundamental component of the standard rock backbeat pattern, but comments on Watts’s drumming have tended to focus on the presence or absence of delay or anticipation of the backbeats and the kick drum rather than the hi-hat eighths. Additionally, Watts typically did not play the hi-hat on beats two and four (see footnote 19, below). Given that some blues-influenced Rolling Stones songs employed swing, potential future research could examine Watts’s use of swung eighths on the hi-hat or ride cymbal. Our microtiming analysis therefore focused on passages either with the standard rock backbeat or a variant. We input data from all quarter-note attacks, even if there was a brief departure from the usual pattern of kick on beats 1 and 3 and snare on beats 2 and 4. For instance, if there was a bar in which the snare or hi-hat, but not the kick, played on beat 1, we would still encode that beat. If no attack occurred on a beat, we did not insert a marker; there would just be a gap in our table. We avoided analyzing songs or parts of songs without a fairly steady stream of quarter-note attacks, so there were rarely a large number of gaps in the passages we analyzed. Once we had markers for all relevant attacks, we exported the data to an Excel template that would automatically calculate measurements such as the length and tempo of each bar and the amount of anticipation or delay of each attack.

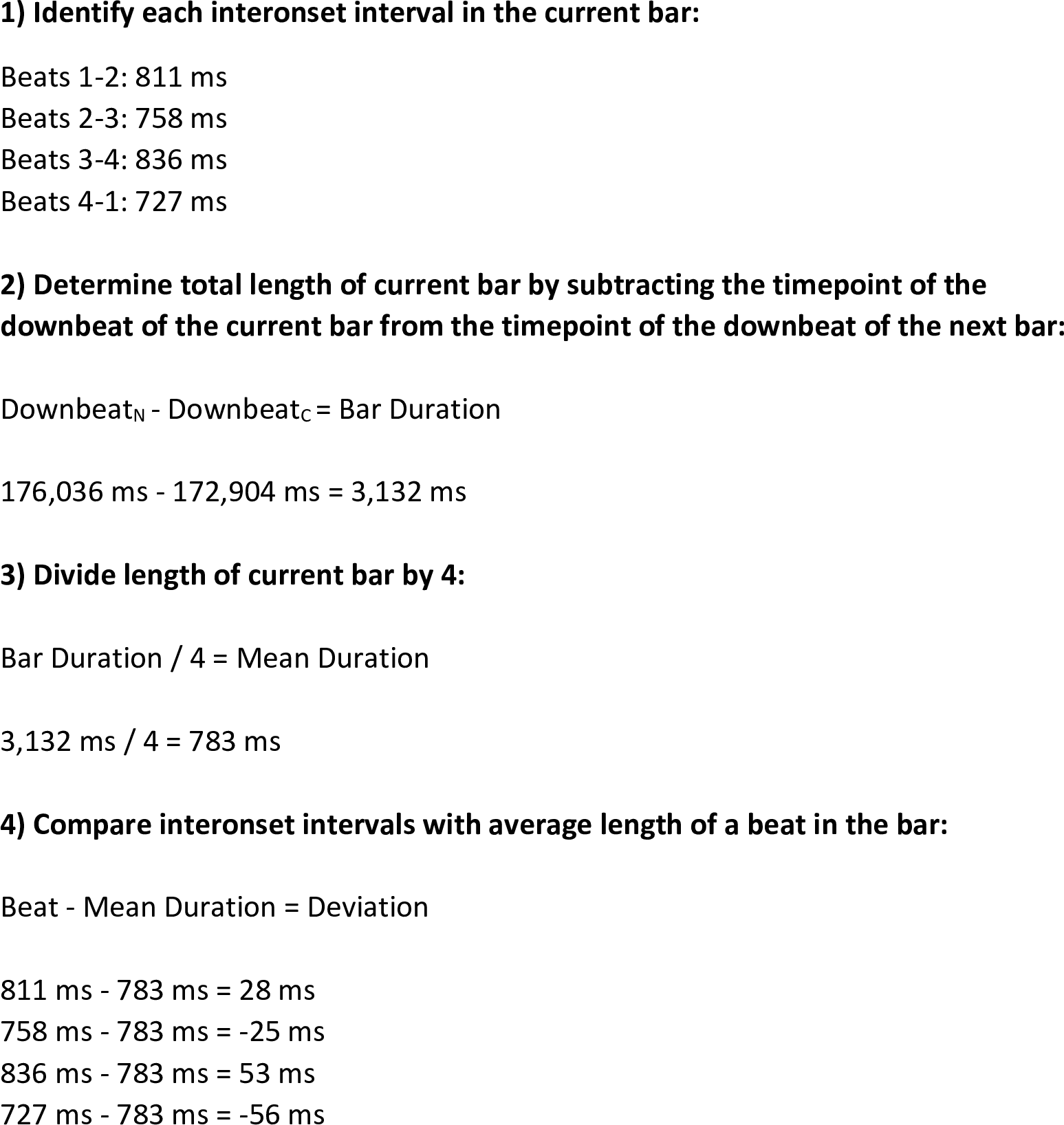

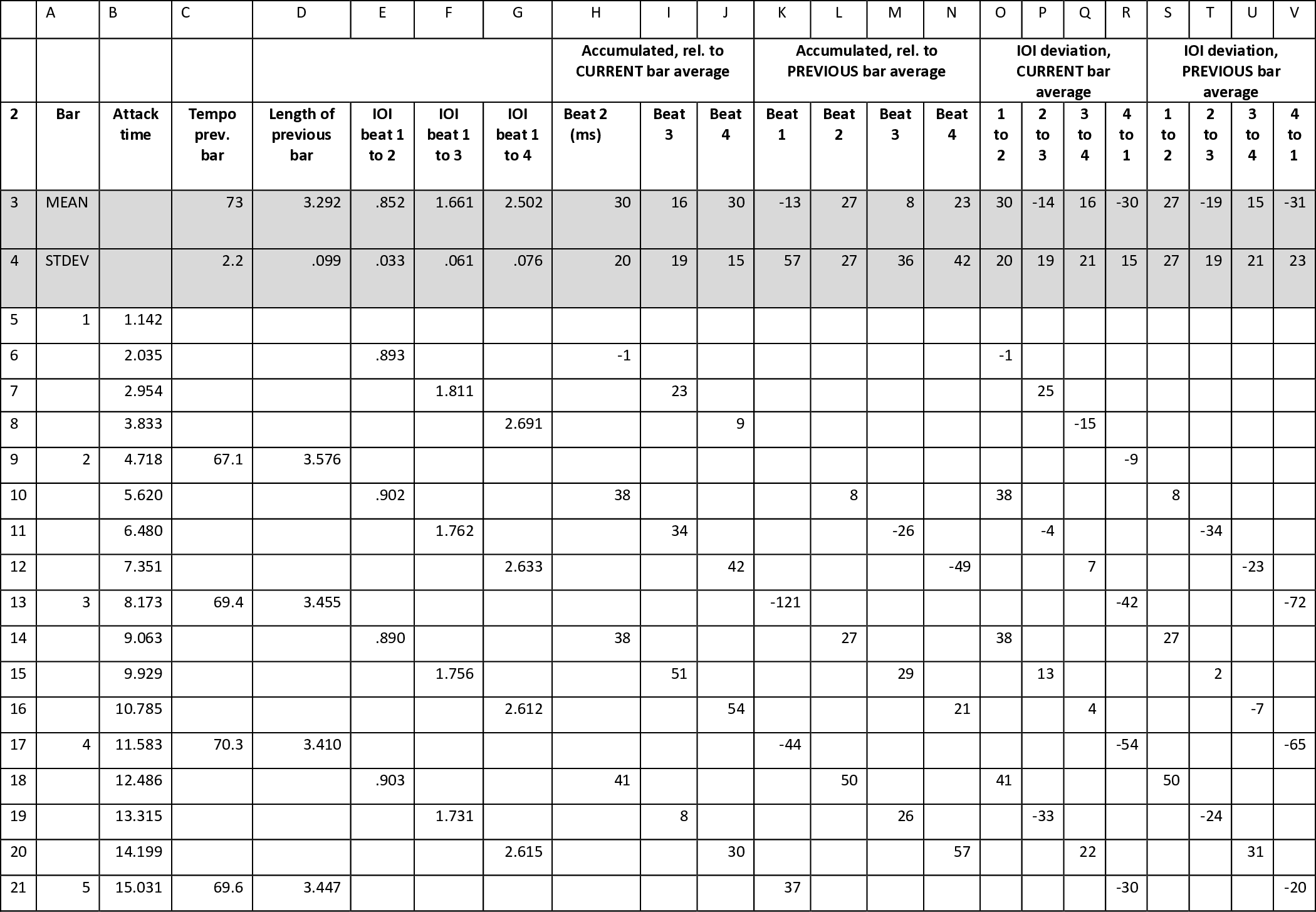

In order to measure whether quarter-note attacks were occurring before or after the beat, it was necessary to identify the locations of these beats in a context in which tempo “drift” was constant (Räsänen et al. 2015, 2). Slight changes of tempo inevitably occur even when a drummer attempts to play steadily. Without a click track (or similar reference), there is no fixed pulse that can be authoritatively identified as the “true pulse.” For this reason, many microtiming studies, such as Kilchenmann and Senn (2015), have drummers record to a click track when creating recordings for analysis. Scientists do not know how many prior attacks the brain accounts for when predicting the timing of subsequent beats. More recent musical stimuli have a greater effect on listener expectations than ones further in the past, but scientific estimates differ as to how quickly listeners disregard earlier information (Bailes et al. 2013, 1). We therefore incorporated a variety of approaches in our research. Prior analysts have sometimes used the current bar as the basis for identifying beats (tempo induction) when the tempo is not steady (see Frane 2017, 296; Freeman and Lacey 2002, 549; and Troes 2017, 35). While this approach evaluates the placement of drum attacks in part on the basis of attacks the listener has not yet heard, listeners to a large extent hear and evaluate music retrospectively (Huron 2006, 13–15), so that they may have an impression of an attack having been delayed only after having heard the bar or even part of the bar in question. Example 2 illustrates our implementation of this approach, calculating the average duration of a beat within the current bar (based on quarter-note attacks marked in Sonic Visualiser) and then comparing the individual measured beat lengths with this average.

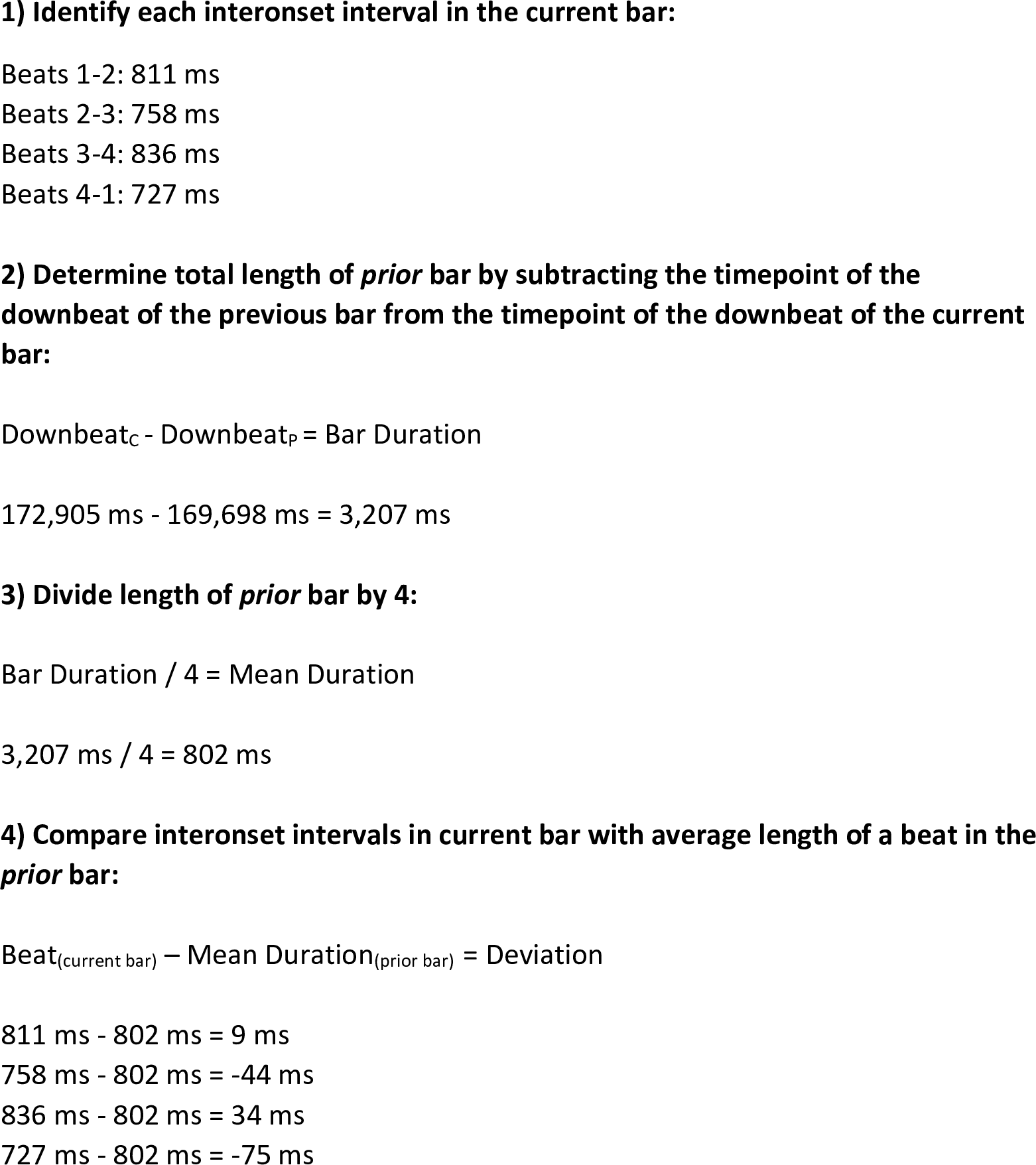

An alternative approach examines what was heard immediately prior to the attacks in question, with these previous attacks creating an expectation for kick and snare placement in the following bar. This method is similar to secondary approaches used by Butterfield (2006, 50–51) and Frane (2017, 296). Butterfield evaluates timing based both on the current measure and on the previous measure. Frane, as a secondary method of measurement, uses only the previous beat as the basis for determining listener expectation. Hellmer and Madison also use previous attacks to predict future ones but rely on the BeatRoot beat tracking system (2015, 152, 154). The BeatRoot system does not examine a fixed past time when making beat predictions, but instead creates initial tempo hypotheses and then reacts to subsequent onset information to adjust the hypotheses (Dixon 2001; Dixon 2007). BeatRoot, however, problematically sometimes snaps beats to actual onsets and often generates beat tracking errors. In implementing this approach, we used the entire bar immediately preceding the bar in question as the basis for calculating beat placement expectation. As seen in Example 3, we compared the interonset intervals (IOI) in the current bar with the average beat length from the previous bar, calculating that average beat length entirely on the basis of the time between successive downbeats. If there was no attack on a downbeat, then that bar could not be used as the basis for a “prior bar” calculation, and the subsequent bar would be excluded from analysis. This provided a positive or negative number indicating whether the attack is ahead of or behind its expected location based on the tempo established in the prior bar. The difference between using the current bar and using the previous bar as the basis for expectation turns out to be relatively small in most cases, though the previous-bar method is more sensitive to significant tempo drift: in particular, if the tempo is accelerating, then the previous-bar method will register slightly less delay than the current-bar method.

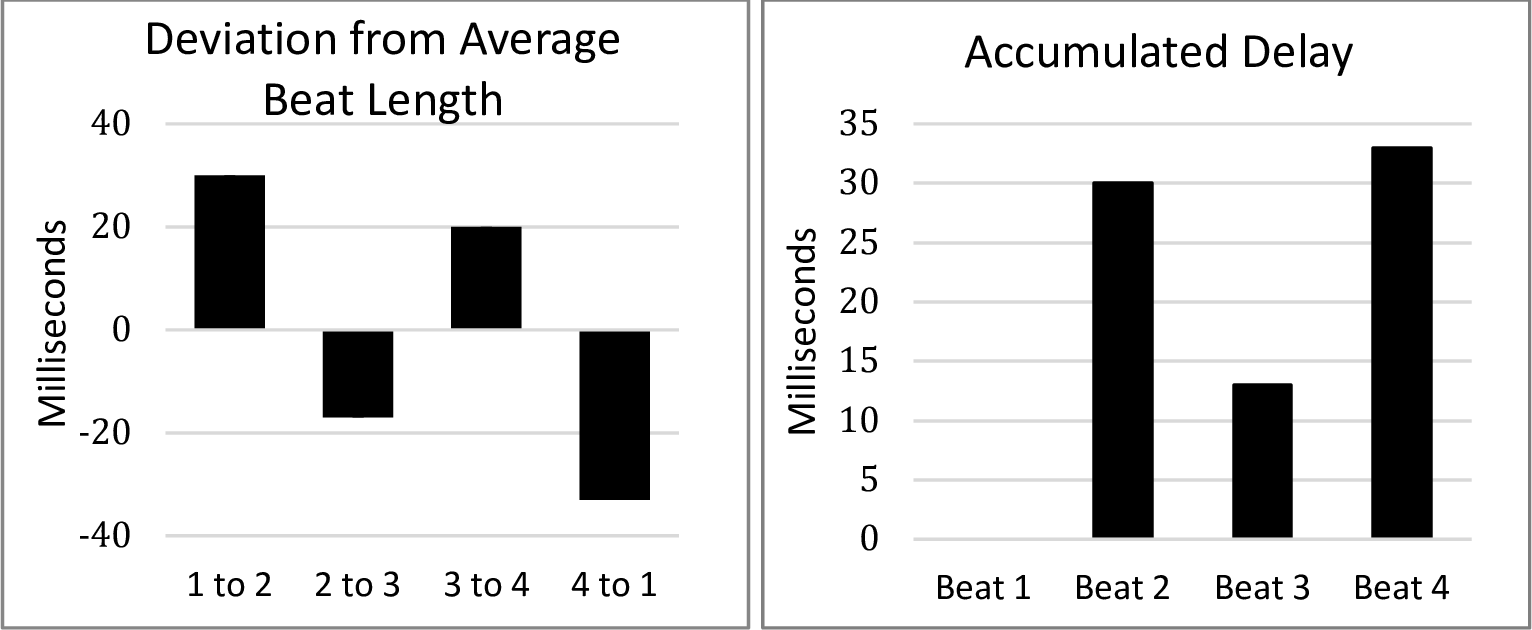

It is important to consider attacks not only in relation to the nearest beat but also in relation to the downbeat of each bar. Doing so is consistent with the importance that listeners assign to downbeats (Butterfield 2007, 8–9) as well as with the practices of drummers who keep the downbeats relatively steady but delay or accelerate within the bar. When asked about playing behind the beat, renowned session drummer John Robinson said that he would keep the bass drum exactly on time but adjust the other attacks around it (Miller 1994, 21–22). Keeping the downbeats steady while playing delayed backbeats requires that the IOI between beats 2 and 3 and between beats 4 and 1 be smaller than average. The asymmetric placement of quarter-note attacks within a relatively steady tempo can be compared to swung eighth notes, where the beat is steady but there is an unequal division of the beat. As Iyer points out, the timing of the kick and that of the snare are interrelated, such that referring to a microtiming deviation as a late snare or as an early kick “is a matter of perspective” (2002, 407). Relatedly, Danielsen discusses how downbeats are expected to be played slightly early in soul and other genres (2006, Chapter 5). Still, the fact that asymmetric division of the bar is more often described as a “delayed backbeat” than an “early downbeat” reflects how the downbeat serves as a point of reference for most listeners. But as seen with beat 3 in Example 4, beat 3 or beat 4 can be heard as late in relation to the downbeat even if the IOI preceding it has a below-average duration. We therefore calculated not only deviation from IOIs but also accumulated delay. Considering the possible approaches of using either the previous or current bar as the basis for beat calculation as well as employing either accumulated delay or individual onsets, we used four calculation methods for each song: accumulated-current, accumulated-previous, IOI-current, and IOI-previous (Example 5). In order to account for listener expectation and the importance of downbeats, we rely on the accumulated-previous approach (using the prior measure to calculate beat expectation and measuring attacks in relation to their distance from the downbeat) as our primary method here. While the other three methods can also provide valuable insights, we rely on one method for simplicity, clarity, and to allow for consistent comparisons between songs. Our focus on the drums does not encompass the contributions to rhythmic feel of the other members of the band. Watts was just one part of the band and reacted to the playing of the other musicians. Individual band members can have contrasting microrhythmic feels (Benadon 2006, 82), and it has been theorized that microrhythmic discrepancies between the drums and bass are crucial to groove in jazz (Butterfield 2010, 157–158). We focused on drums in this project for the sake of simplicity and because the precise timing of drum attacks can more reliably be specified than that of bass or guitar attacks. Our discussion below primarily focuses on the application of this method to analysis of beat 2, in part because Watts and other artists showed similar tendencies with regard to beats 2 and 4, There was a fairly strong correlation between the mean beat 2 and mean beat 4 deviations in a song; see footnote 17 below. but also because using the accumulated decay approach results in the same values for beat 2 as using IOIs.

We employed multiple approaches to measuring the significance and potential perceptibility of deviations from expectation. The positive or negative measurements in milliseconds (indicating whether an attack was relatively late or early) were compared with a hypothesized zero deviation via a two-sided one-sample t-test, providing a p-value that indicates whether the mean deviation was statistically significant. We also calculated the percentage of second and fourth beats in each song that were delayed by the 2.5 percent of mean IOI standard of conscious perceptibility (discussed above; hereafter referred to as “the 2.5 percent of mean IOI threshold” or “substantial” delay). While the perception of microtiming deviation likely depends not only on the measurable timing but also on factors such as timbre, duration, amplitude, the listener’s musical training, and the activity of the other instruments in the texture (Danielsen et al. 2019; Frane and Shams 2017; Butterfield 2007, 19), 2.5 percent of mean IOI can be thought of as the lower end of possible conscious recognition by a musically trained listener. We have thus used this threshold as a benchmark in our statistical evaluations. Madison and Merker’s finding (2004, 71) that musicians can react to deviations from isochrony as small as 1.5 milliseconds suggests that discrepancies smaller than 2.5 percent of IOI could change the “feel” of a Stones recording for a listener even if they would not be able to consciously recognize such small deviations.

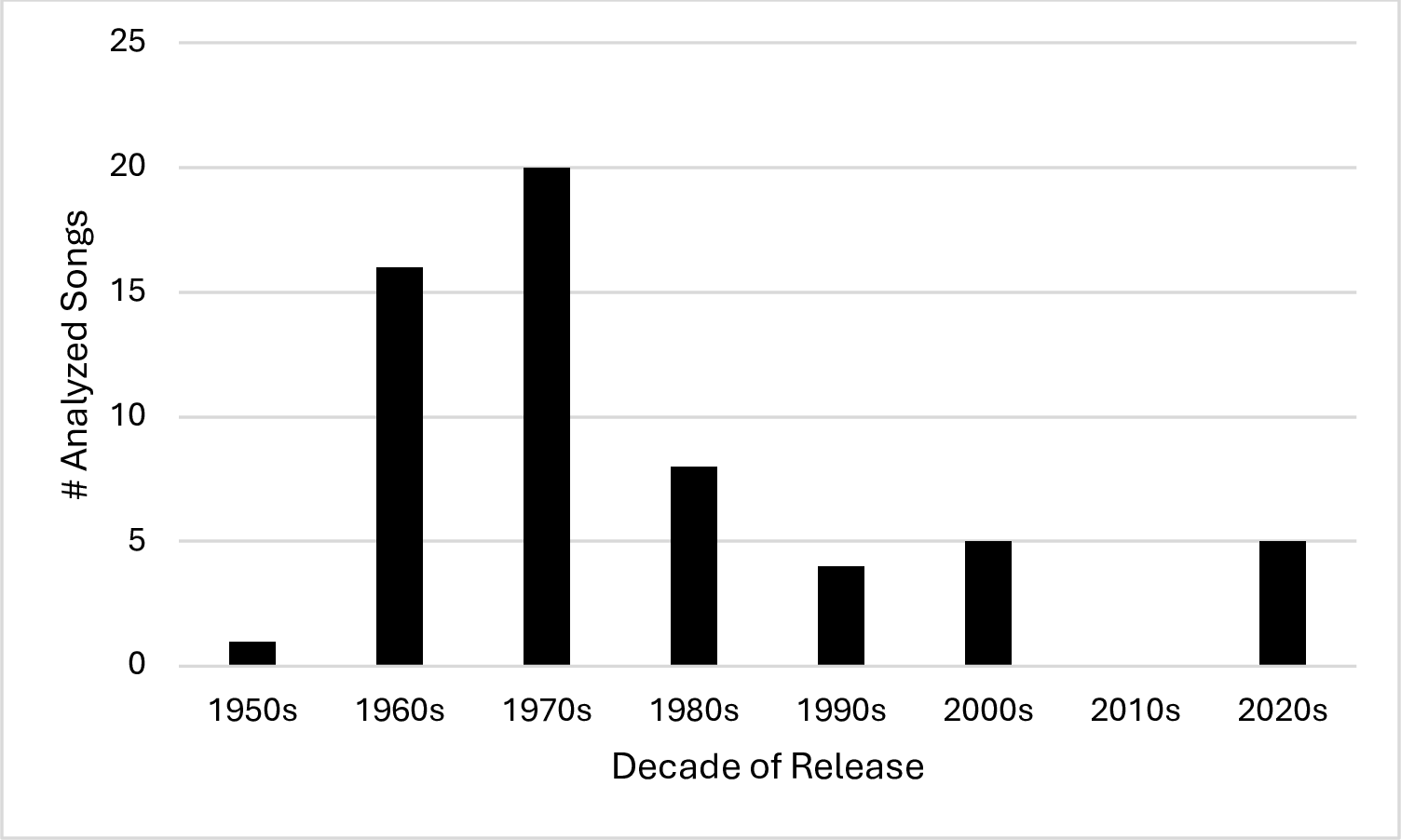

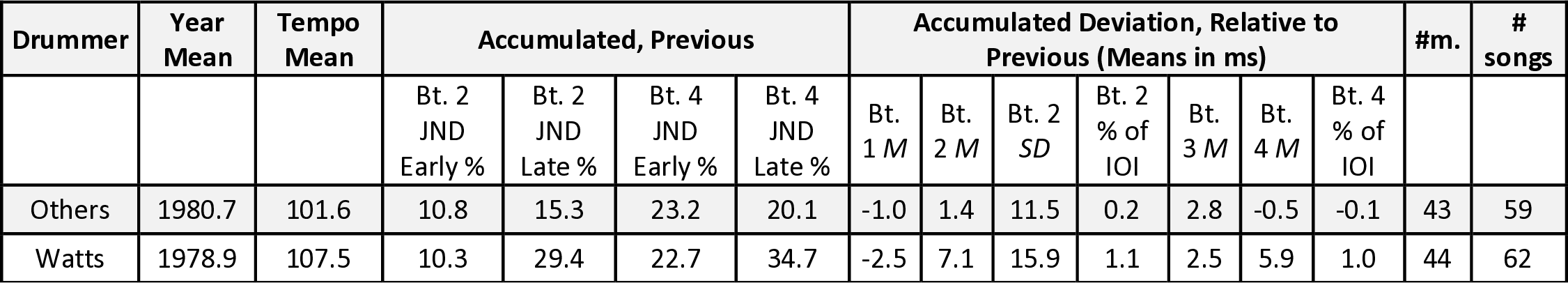

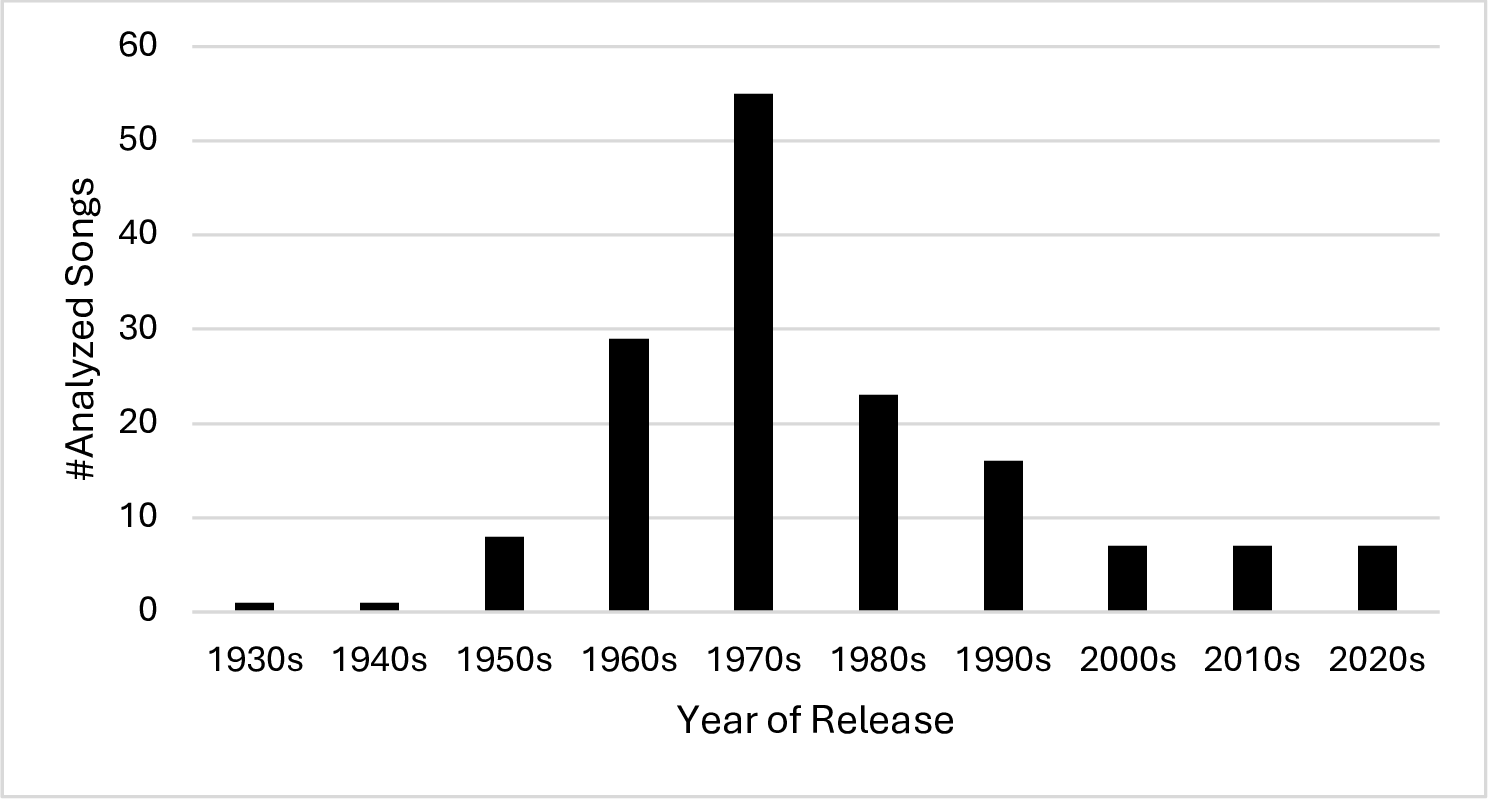

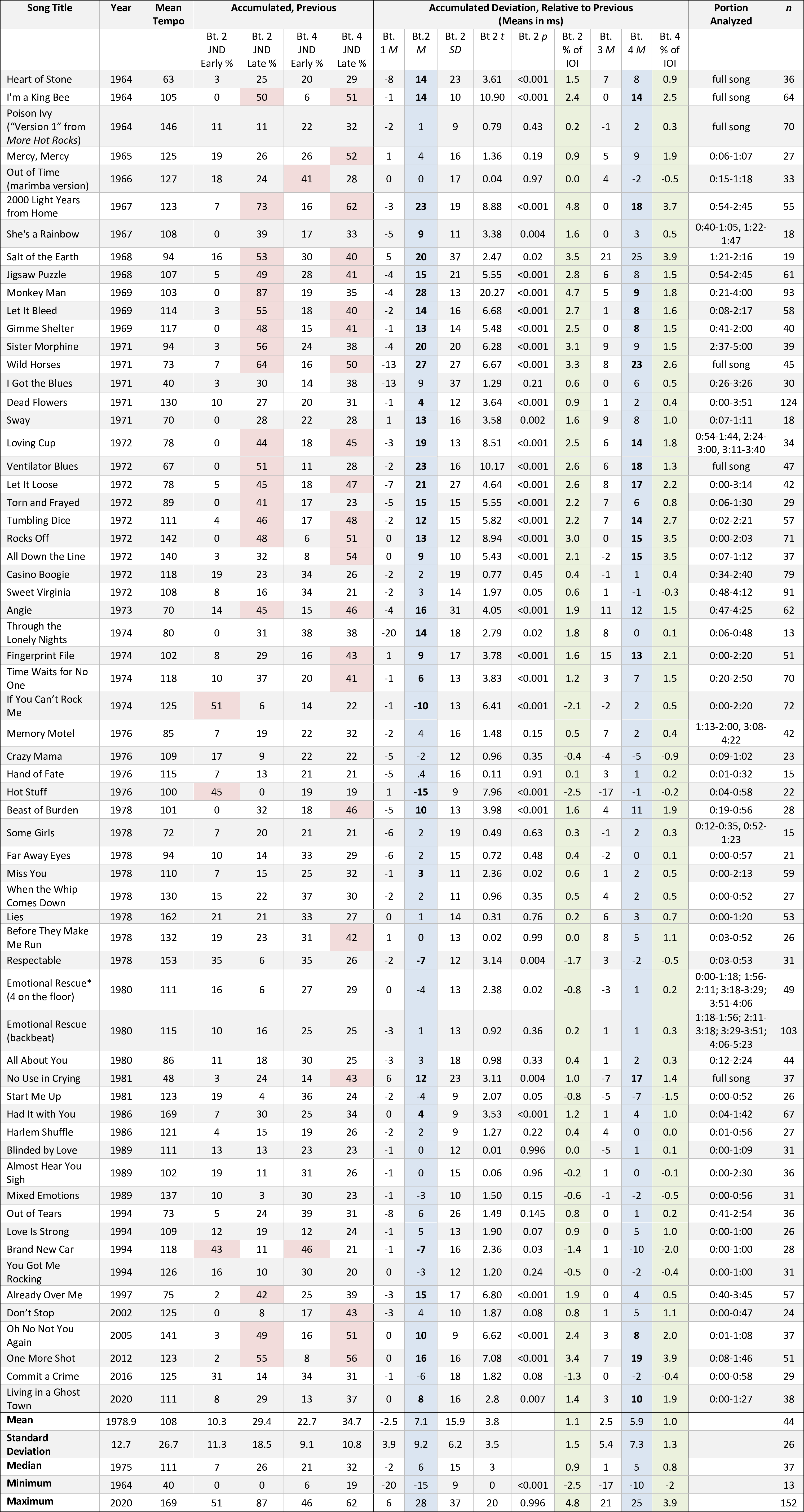

We analyzed 62 Rolling Stones studio recordings with Watts on drums for microtiming (Appendix Example 1 ), 19 Stones live recordings (see Example 15, below), and 59 recordings by other artists contemporary with the Stones (including three Stones tracks with a different drummer; Appendix Example 2), focusing on songs containing passages with a rock backbeat pattern or variant. In most instances, the microtiming analysis we did for a given song is of a subset of the song’s entire length. This was in large part to focus on passages where there is a standard rock backbeat pattern or variant and where there were not too many fills or syncopations that would interfere with marking quarter-note attacks. This approach prioritized obtaining samples of more songs over doing analyses of a smaller number of full songs. The 19 Stones live recordings we analyzed include selections from each of the first six decades of the band’s career and represent a variety of tempos (Example 6). We analyzed a relatively small number of songs from the 1960s (even though the Stones released a large number of studio recordings during that decade) because the inferior recording technology of the era often makes it difficult to accurately identify the placement of kick drum attacks. Example 7 shows the breakdown by decade of analyzed songs by other artists, which predominantly use the standard rock backbeat or a variant. These songs were selected to serve as rough chronological and stylistic analogs of the Stones songs we analyzed or because they sounded like they might have particularly delayed or early backbeats.

III. Microtiming Study Results

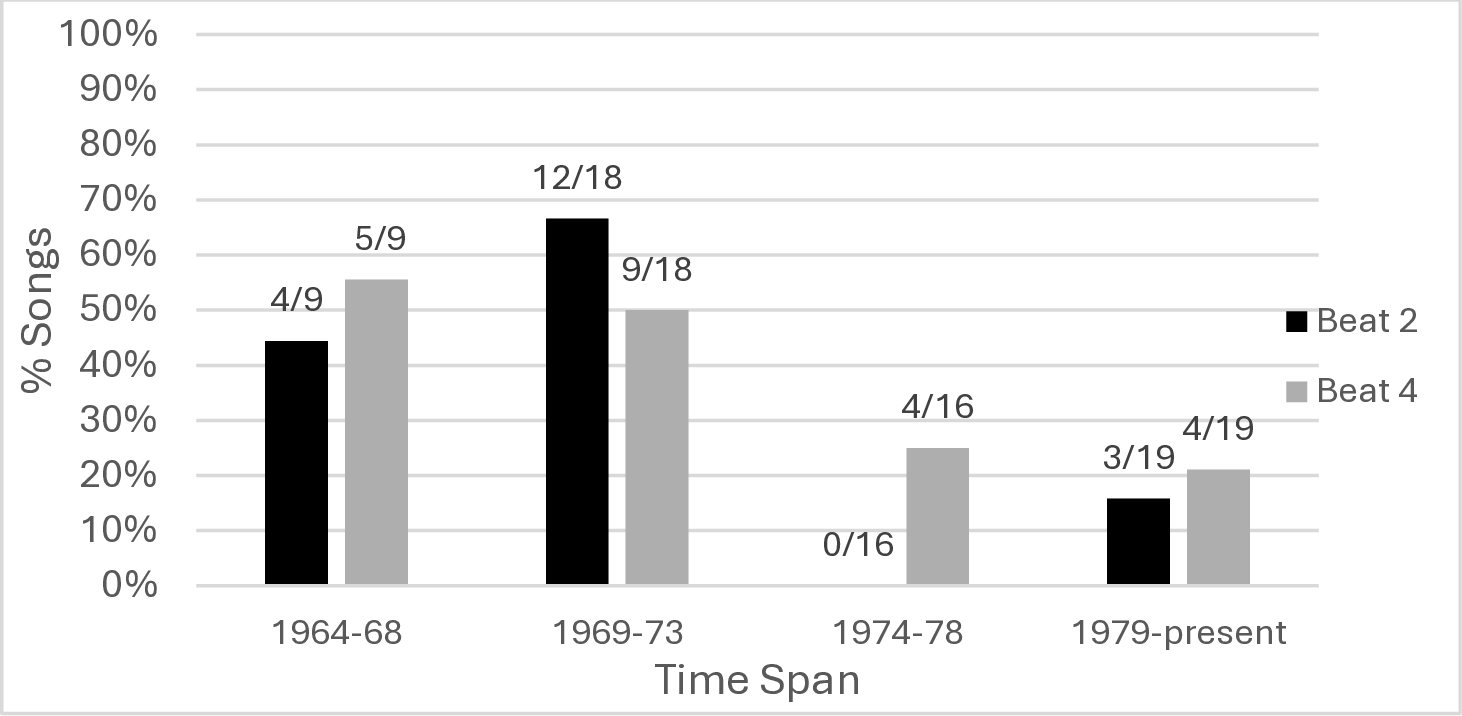

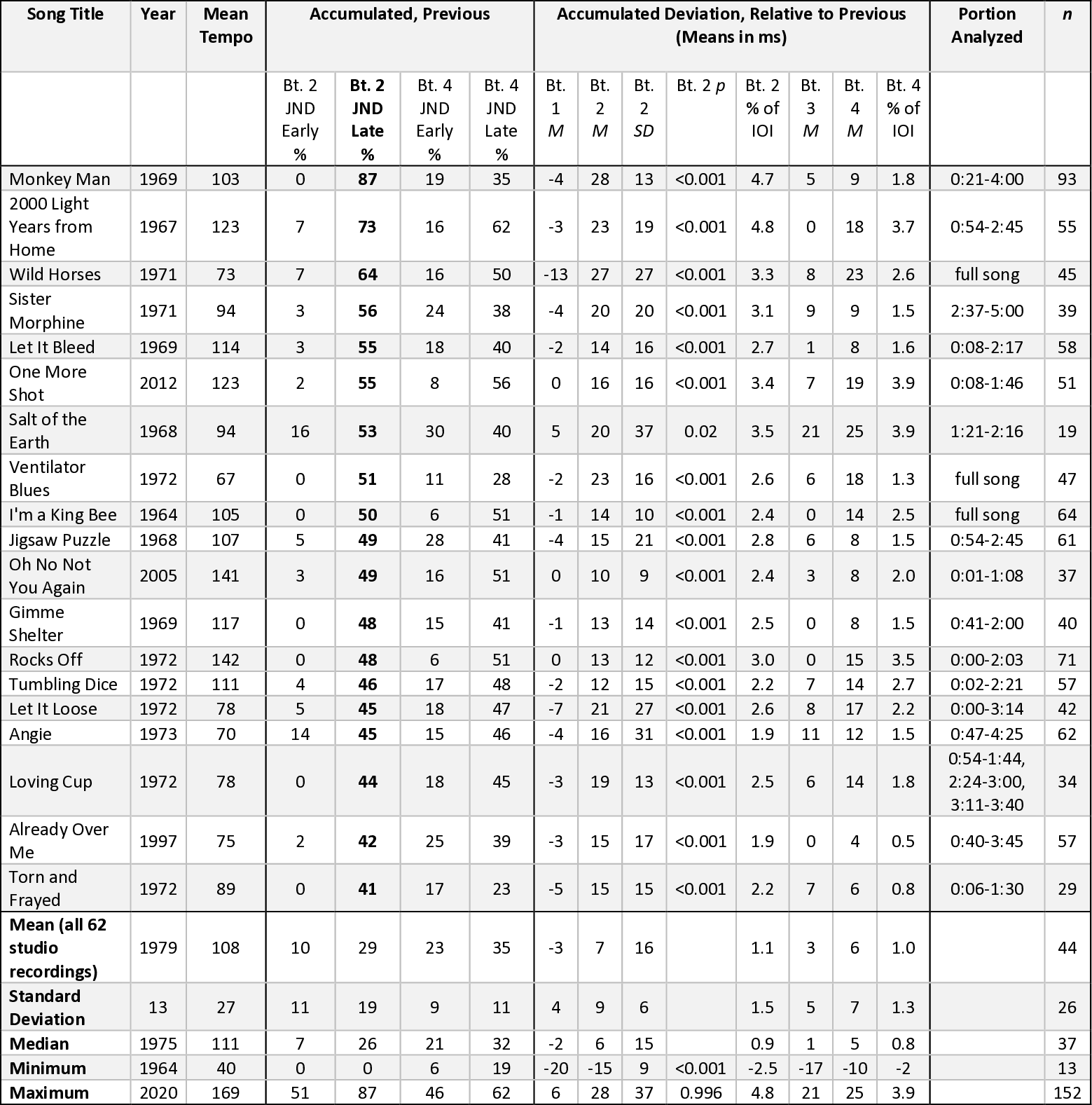

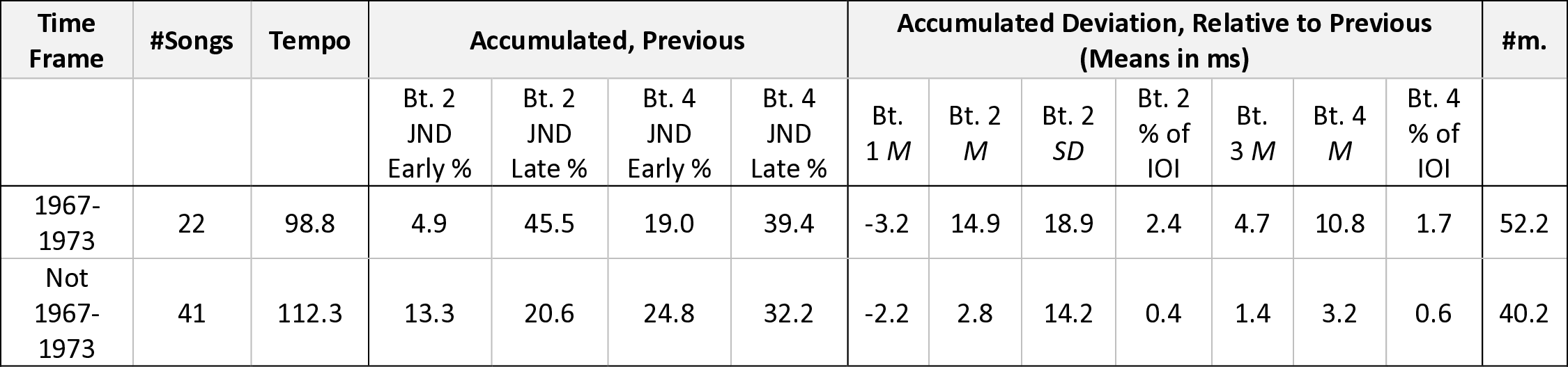

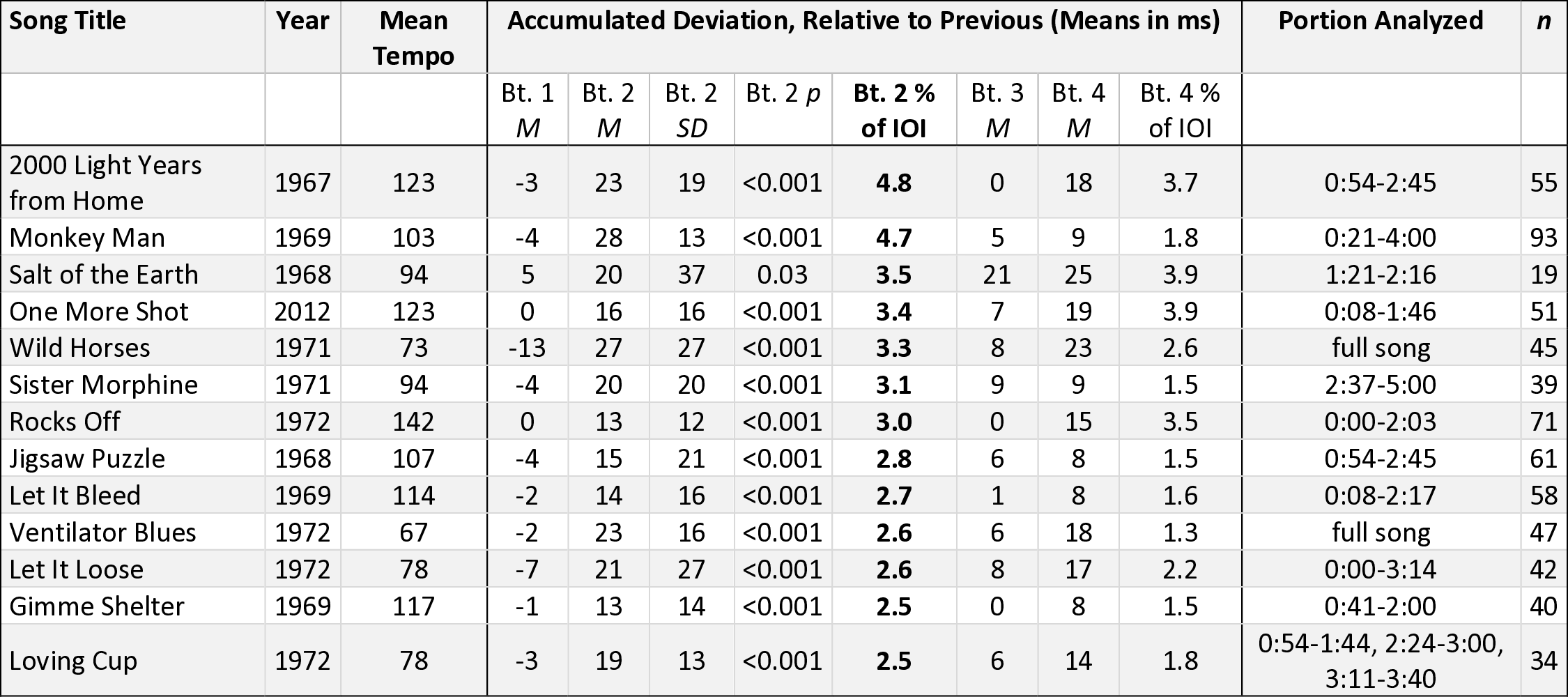

Our analysis of microtiming examines delayed backbeats in the drumming of Watts and how his approach compares with his contemporaries. Our results reveal that microtiming deviations in Watts’s drumming varied over the course of his career. As shown in Example 8, of the 19 Stones studio recordings with the highest percentage of substantially delayed beat 2 attacks, 12 were released between 1969 and 1973. When the period is expanded by two years to 1967–73, it accounts for 15 of the 19 (Example 9; Appendix Example 1 shows the results for all analyzed songs). Example 10 compares the data for Watts for 1967–73 with that for the rest of his career, showing how he substantially delayed a much greater percentage of his beat 2 attacks in this period (45.5 percent) than in the rest of his career (20.6 percent). Watts also substantially delayed beat 4 attacks more in the 1967–73 period (39.4 percent) than in the remainder of his time in the band (32.2 percent). Considering the entirety of Watts’s career, there was a fairly strong correlation between the average amount of delay of beat 2 in songs and that of beat 4, with r = .81 for the 62 Watts studio recordings. The recordings with the most consistent beat 2 delays, however, were not always those with the most consistent beat 4 delays. “Monkey Man” and “Sister Morphine,” for instance, showed strong tendencies towards beat 2 delay but not for beat 4, while the reverse was true of “All Down the Line.” There was a similar correlation between delay of beat 2 and beat 4 in the 59 analyzed recordings with other drummers, with r = .84.

After 1973, however, examples of consistent backbeat delay in Watts’s drumming are rare. We found only three Stones studio recordings released after 1973 (out of 35 analyzed from this period) that substantially delay at least 40 percent of their beat 2 attacks: the ballad “Already Over Me,” the up-tempo “Oh No Not You Again,” and “One More Shot” (Example 9). In his 2012 review of “One More Shot,” Neil McCormick wrote that Watts’s “swinging beat [was] just that micro-fraction behind where you might expect it to be.” “Oh No Not You Again” and “One More Shot” also substantially delay at least 40 percent of their beat 4 attacks. An additional six recordings dating after 1973 (two of them from 1974) delay at least 40 percent of their beat 4 attacks more than the 2.5 percent of mean IOI threshold, but the percentage of songs meeting this standard for beat 4 is similarly much lower after 1973 than before (Example 8). And while there are patterns of consistent delay in numerous Stones recordings, our evidence suggests that even during the 1967–73 time period (in which the most delayed backbeats were found), some songs—such as “I Got the Blues,” “Casino Boogie,” and “Sweet Virginia”—lacked consistent backbeat delay. Stones guitarist Keith Richards has linked the practice of delaying the backbeat to Watts’s idiosyncratic habit of not playing the hi-hat when he hits the snare (Richards 2010, 121). Despite Richards’s claim, there is little evidence that Watts’s habit of not hitting the hi-hat on beats 2 and 4 caused him to play behind the beat. The fact that Watts did not always play behind the beat when using the technique calls into question Richards’s contention. Video of the Stones playing “I Got the Blues” (The Rolling Stones 2022), for instance, clearly shows Watts using this technique, but analysis of this performance reveals that he played the backbeats consistently early. Also undermining Richards’s theory is the fact that the snare is at times delayed when Watts uses the ride cymbal instead of the hi-hats for eighth-note subdivisions, as in the studio recordings of “Angie” (1:43–1:56) and “No Use in Crying” (0:40–1:00); Watts typically played all eighth-note subdivisions when playing the ride. Even in the songs that show the most consistent delay, there is a great deal of variability from attack to attack, with the standard deviations for the placement of beat 2 in the songs in Example 9 primarily ranging between 10 and 20 ms. Thus, while a tendency towards delay is clear in numerous songs between 1967 and 1973, there appears to be a significant element of randomness as far as the exact amount of delay.

Another measure of the amount of beat 2 delay in a song is the mean deviation from expectation, expressed as a percentage of the mean beat length for the song. A review of the songs with beat 2 mean percentage delays of at least 2.5 percent of IOI (Example 11) similarly shows that the most extreme songs in this regard generally came from the 1967–73 period. Of the 13 songs in Example 11 that meet this standard, all except for “One More Shot” date between 1967 and 1973. The mean percentage delay of beat 2 in the 1967–73 period was 2.4 percent, while outside of that period it was only 0.4 percent; beat 4 delays were also higher in the 1967–73 period (1.7 percent versus 0.6), as seen in Example 10. The mean amounts of delay seen in Example 11 (measured in milliseconds) are for the most part similar to or greater than the mean snare delays of 17 ms by the drummers studied in Câmara et al. (2020, 11) and Danielsen et al. (2015, 2306) who were instructed to play in a “laid-back” manner. The mean standard deviations in these studies ranged between 11 and 19 ms, with smaller standard deviations at faster tempos. The standard deviations in Watts’s playing shown in Example 11 tend to be somewhat greater, which is unsurprising given that Watts was not playing with a click track (see section V, below), while the drummers in the Câmara et al. and Danielsen et al. studies were playing with either a metronome or a tempo invariant backing track. Five tracks, four of them released between 1967 and 1971, rank particularly high on both the most consistent delay and greatest percentage delay lists: “2000 Light Years from Home,” “Monkey Man,” “Wild Horses,” “Sister Morphine,” and “One More Shot.” Of these, “2000 Light Years from Home,” “Wild Horses,” and “One More Shot” also have a strong tendency towards beat 4 delay. While the rootsy, laid-back feel and relatively slow tempos of “Wild Horses” and “Sister Morphine” are consistent with the typical musical associations of delayed backbeats discussed above in section I, “2000 Light Years from Home,” with its fast tempo and provocative sci-fi soundworld, and “Monkey Man,” with its sophisticated-sounding extended tertian harmonies and polished production, clash with these associations. Both “2000 Light Years” and “Monkey Man,” however, have relatively active, syncopated kick patterns (Example 12), an approach associated in our study with backbeat delay and its complement, an early kick drum. The syncopated kick patterns in “Sister Morphine” and “One More Shot” provide additional examples. While syncopated kick patterns tended to be associated with backbeat delay in our study, songs with simple, unsyncopated kick patterns tended towards early backbeats; see our discussion of early backbeats, below.

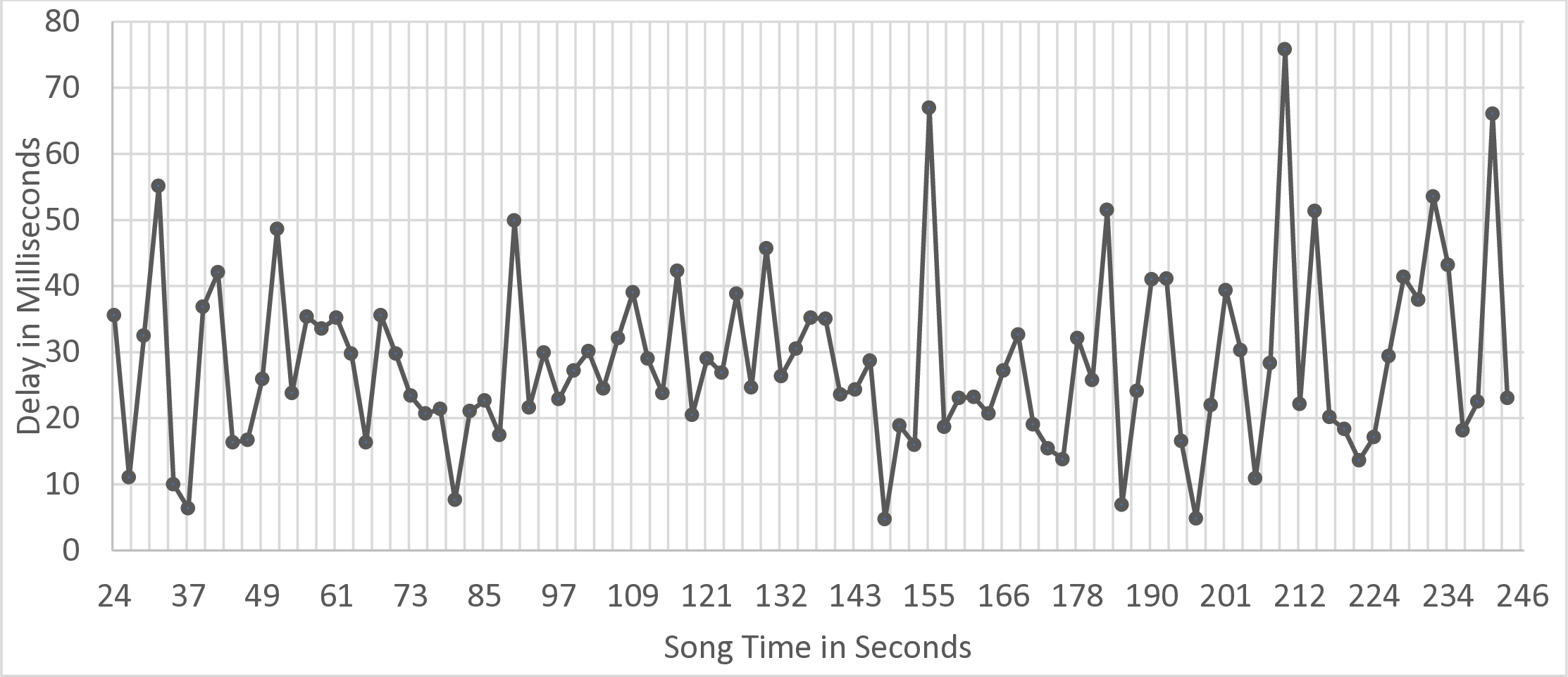

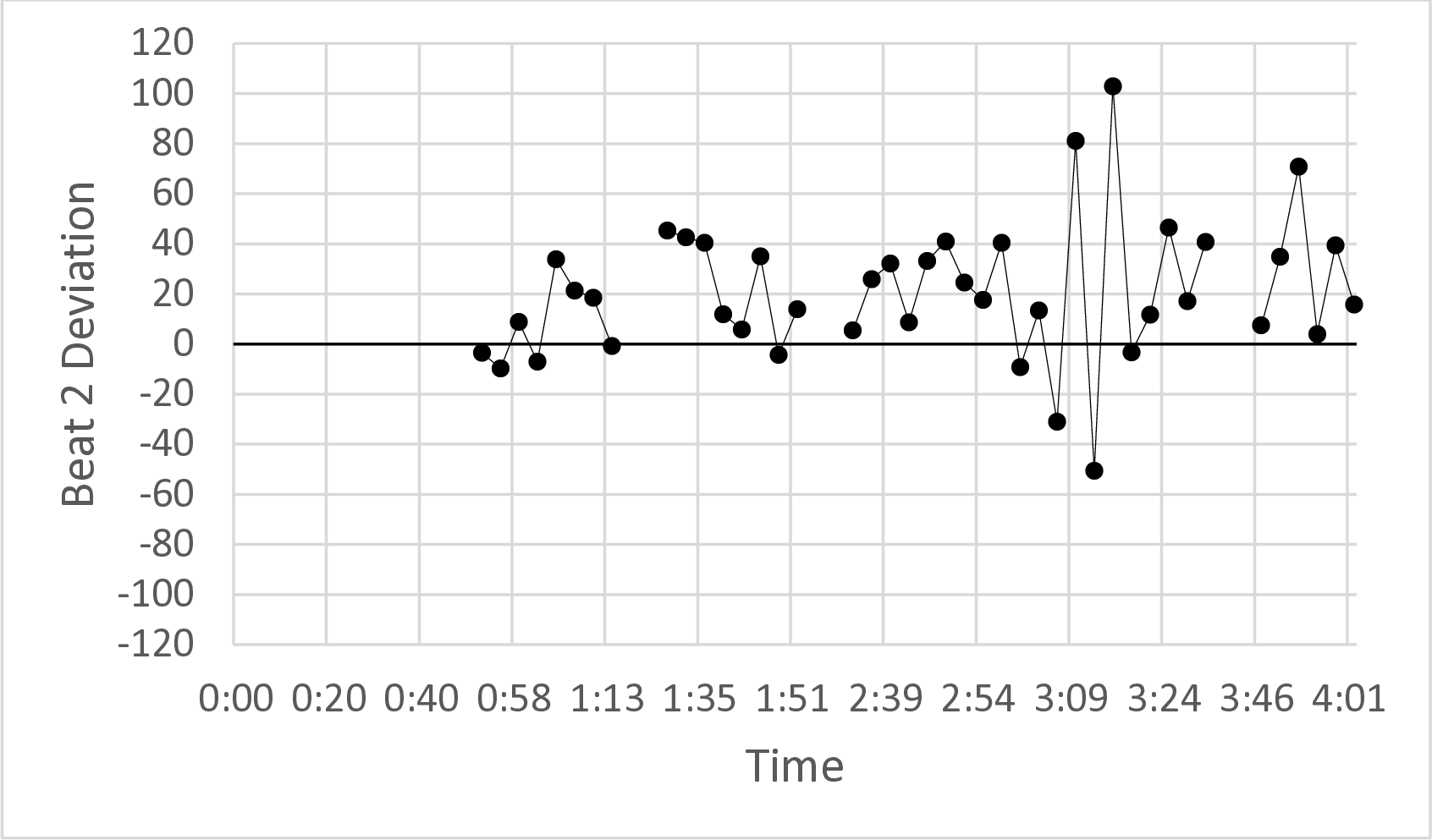

In “Monkey Man” (1969), beat 2 delay varies between 10 and 80 ms, but the second beat is always late, as seen in Example 13. This is despite the overall pattern of acceleration in the song (see section IV, below). There is also a tendency towards beat 4 delay (mean of 9 ms) in “Monkey Man,” though this tendency is much less pronounced than it is for beat 2 (with a mean delay of 28 ms). The delayed backbeats in the song reflect the narrator’s “lazy” lifestyle, in which he “always has an unmade bed,” is compared to “broken eggs” and “cold pizza,” and “loves to play the blues.” Looking at the beat 2 microtiming graph in more detail, we see that while all the beat 2 attacks are late, there is generally alternation between high and low delay values rather than a clustering of one or the other. There are only a few spots in “Monkey Man” where there are four or five consecutive beat 2 attacks with similar amounts of delay, most notably at 0:56–1:03 (delays between 30 and 35 ms), at 1:32–1:46 (seven consecutive delays between 22 and 32 ms), and at 2:36–2:43 (delays between 19 and 23 ms). Two of these three relatively consistent areas occur at formally analogous points: 0:56–1:03 is the second half of the first verse, where the harmony shifts to ♭VI and the refrain occurs, while 1:32–1:46 roughly aligns with the second half of the second verse, with the same harmonic change and the refrain. This formal echo recalls both Iyer’s claim that microtiming deviations “convey information about musical structure” (2002, 397) and Hellmer and Madison’s supposition that microtiming patterns can correspond with particular section types (2015, 158). Other than this correspondence, however, there is no clear pattern in beat 2 delay lengths over the course of the song; instead, just a slight trend towards greater delay in the second half of the recording, with six of the seven largest delays occurring there. Butterfield writes that “competent” drummers tend to “fairly consistently” place their attacks either on top of or behind the beat (2006, 36). Looking at the microtiming of “Monkey Man” and other songs in detail suggests that, while consistent placement behind or ahead of the beat is possible for a drummer playing without mechanical assistance, the amount of displacement may be highly variable even with an expert drummer. Fittingly, the portion of the song with the most extreme levels of backbeat delay, both early and late, is the chaotic outro, with cymbal crashes, drum fills, and Mick Jagger’s vocal improvisations.

Like “Monkey Man,” the 1972 Stones album Exile on Main Street contains some of the clearest and most consistent examples of delayed backbeats. The album was produced by drummer Jimmy Miller, whose time working with the band (1968–73) appears particularly correlated with delayed backbeats and tempo variability (see sections IV and V, below). “Ventilator Blues,” “Rocks Off,” “Tumbling Dice,” “Let It Loose,” “Loving Cup,” and “Torn and Frayed” each contain relatively consistent and substantial backbeat delays, though other tracks from the album, such as “Casino Boogie” and “Sweet Virginia,” lack such a tendency. The gospel-inflected “Let It Loose” from this album provides an example of a strong tendency to delay the snare on beats 2 and 4 (Example 14). In this song, the average delay of the attack on beat 2 in comparison with the expectation created by the previous bar is 21 ms, and the average accumulated delay for beat 4 is 17 ms. Of the 42 beat 2 attacks, 19 (45 percent) are delayed by at least 2.5 percent of mean IOI, and 32 (76 percent) are delayed by at least 5 ms. The substantial delays to beats 2 and 4 are mostly consistent, with the exception of a passage at 3:03–3:21 that has a less steady tempo and extensive drum fills.

We found only three Stones studio recordings where at least 40 percent of the beat 2 attacks were early by at least 2.5 percent of mean IOI: “If You Can’t Rock Me” (1974), “Hot Stuff” (1976), and “Brand New Car” (1994). “If You Can’t Rock Me” features a simple, unsyncopated kick pattern—often using just single attacks on beats 1 and 3—and a relatively busy snare drum with frequent fast fills. “If You Can’t Rock Me” is the earliest Stones track we found with a mean beat 2 delay of less than zero (indicating that beat 2 attacks were on average early) with all 27 analyzed tracks released prior to 1974 having a mean beat 2 delay greater than zero. In contrast, of the 19 analyzed tracks from 1980 onwards, eight of them (42 percent) have negative beat 2 mean deviations. “Hot Stuff,” a disco track that is one of the band’s steadiest recordings prior to the 1980s (tempo CV of 0.66; see section V, below), similarly features a very simple kick pattern with single attacks on beats 1 and 3, as does the later “Brand New Car.” Iyer wrote that the four-on-the-floor kick drum approach, another pattern associated with disco that involves no syncopation or eighth notes in the kick, was incompatible with delayed backbeats because it eliminated or at least reduced the timbral difference between the downbeats and the backbeats (2002, 406), yet its incompatibility with backbeat delay and its complement, an early kick, may be more related to the simplicity of its kick pattern. The Stones song “Emotional Rescue” exemplifies the tendency towards early backbeats when a four-on-the-floor pattern is used, as the verse four-on-the-floor pattern shows a significant tendency towards an early beat 2 and the backbeat pattern in the bridges and outro lacks this tendency (see Appendix Example 1).

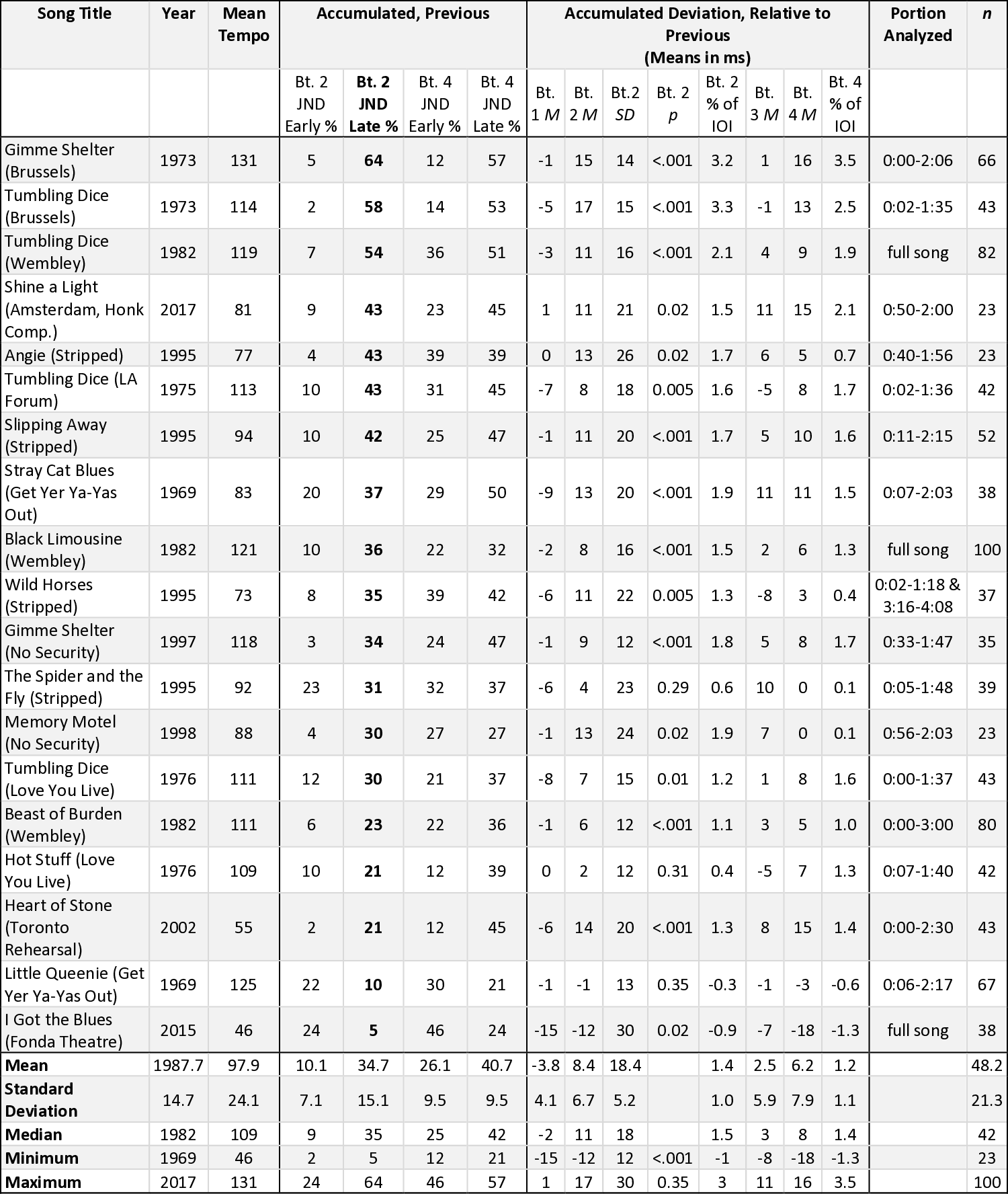

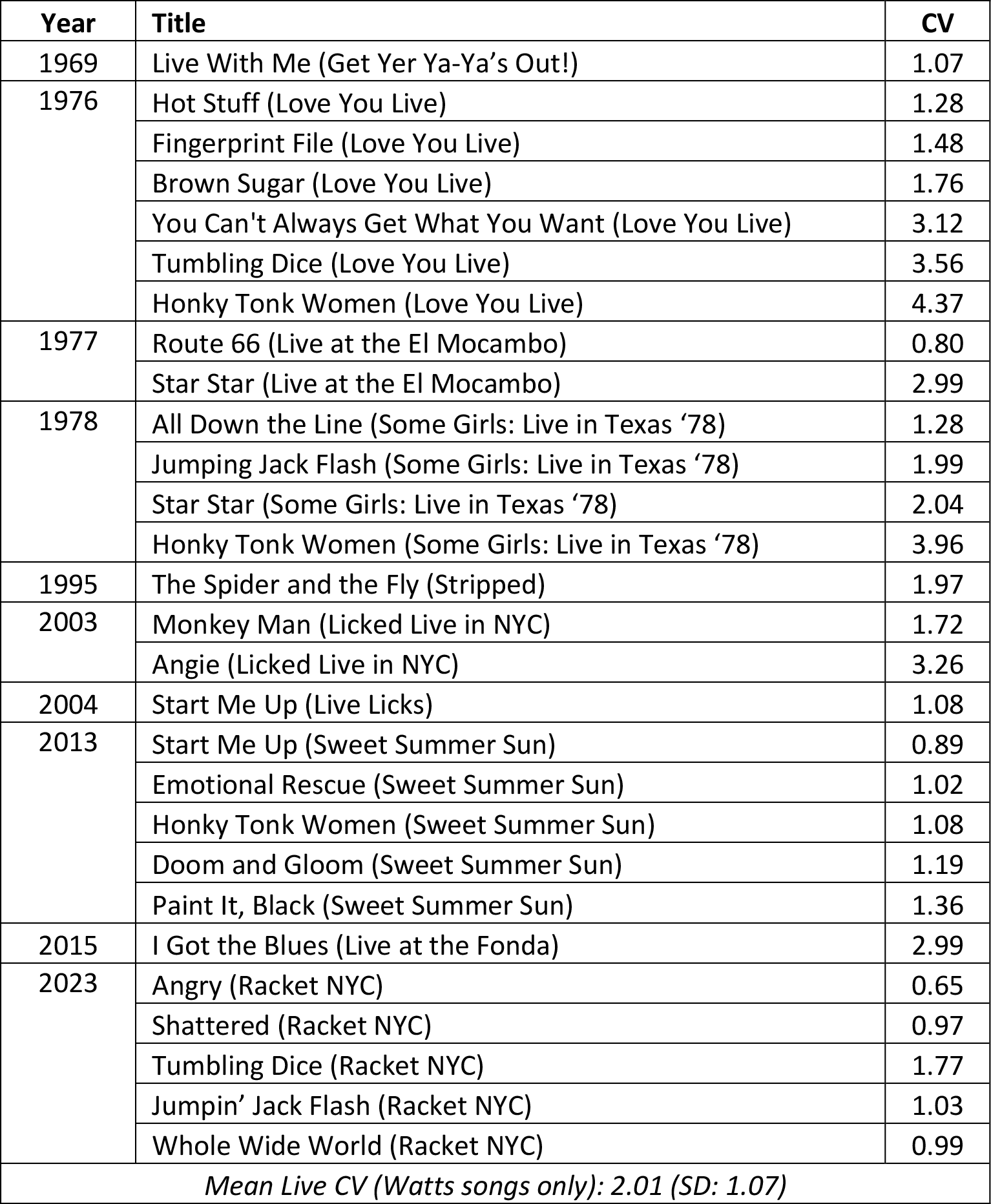

Looking at microtiming in Rolling Stones live recordings with Watts, there are also instances of relatively consistent backbeat delay, with 7 out of 19 recordings having at least 40 percent of their beat 2 attacks meeting the 2.5 percent JND threshold and 10 recordings meeting that standard for beat 4 (Example 15). The band’s 1973 Brussels rendition of “Gimme Shelter” had the most consistently delayed second beats, while the four live recordings of “Tumbling Dice” we analyzed showed a pattern of backbeat delay similar to that in the studio recording. The consistency with which the Rolling Stones have performed this song with delayed backbeats in both studio and live settings suggests that the approach is a crucial component of it. Watts’s use of delayed backbeats in live performances of several Stones songs continued even through the era in which he largely gave up playing with delayed backbeats in the studio, as live recordings of “Shine a Light,” “Angie,” “Gimme Shelter,” and others from the 1990s and twenty-first century attest.

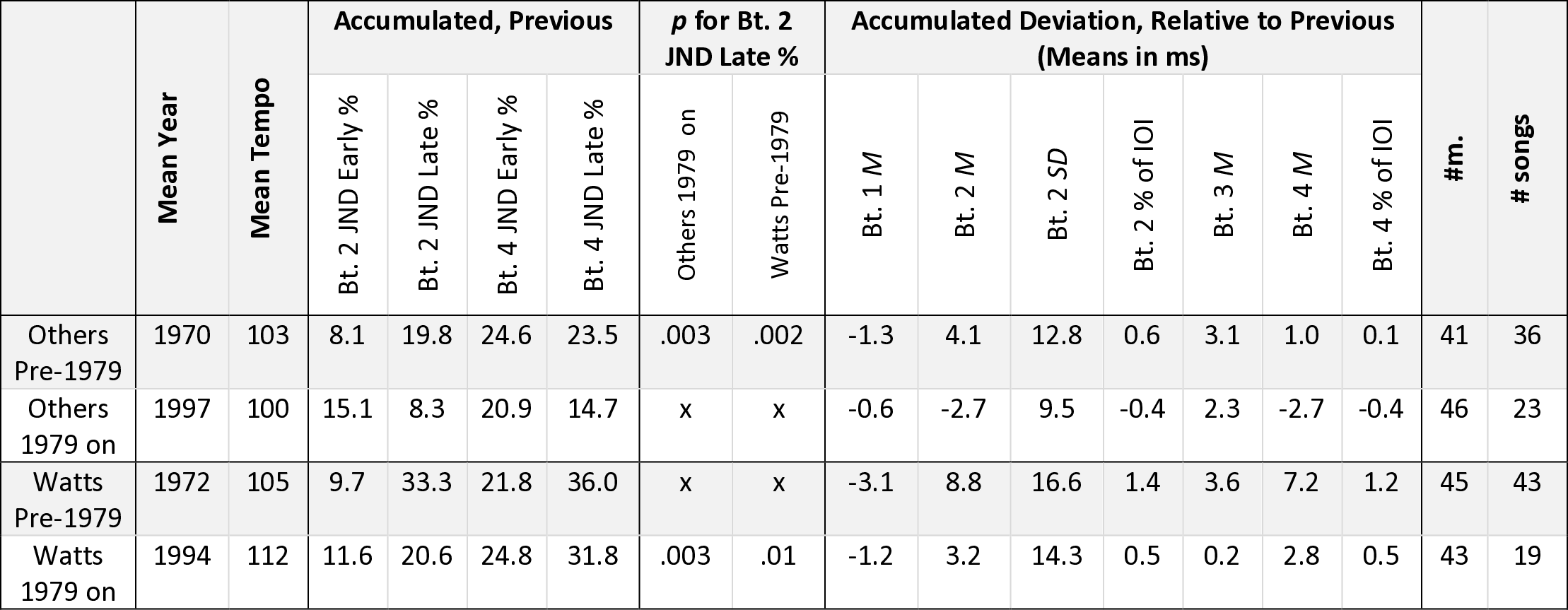

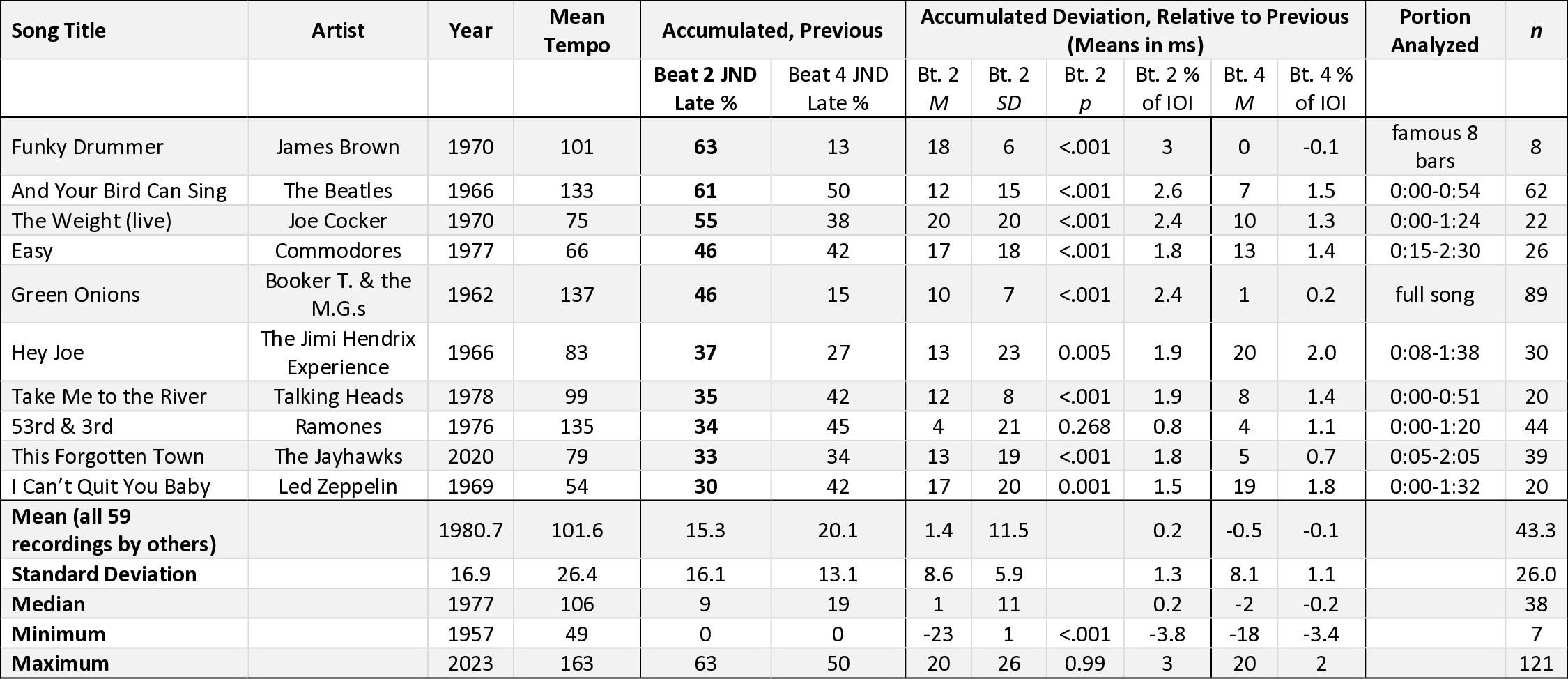

In order to better understand how Watts’s microtiming tendencies compare with those of his contemporaries, we also analyzed 59 recordings with other drummers (Appendix Example 2). Prior to 1979, other drummers delayed by at least 2.5 percent of mean IOI an average of 20 percent of second beats, while from 1979 on this number fell to just 8 percent (Example 16). On average, other drummers prior to 1979 delayed beat 4 slightly less than beat 2, though not to a statistically significant extent (p = .10). In his study of microtiming in famous breakbeats, Frane found significantly more tendency to delay beat 2 than beat 4 (2017, 299), but we did not find this to a statistically significant extent with either Watts or the group of other artists. We found a relatively small number of recordings of other drummers, all but one from prior to 1979, with a tendency towards substantial delay (Example 17). While just three recordings we analyzed had more than 50 percent of their second beats substantially delayed (including the famous eight bars of James Brown’s “Funky Drummer”), several more prior to 1979 had an average beat 2 delay of at least 2.5 percent of mean IOI, including “Easy” by the Commodores (1977), “Hey Joe” by the Jimi Hendrix Experience (1966), and “Take Me to the River” by Talking Heads (1978). Al Jackson Jr., who Max Weinberg referred to as a pioneer of playing behind the beat (Beaumont-Thomas 2021), delays beat 2 consistently on “Green Onions” and to a lesser extent on Sam & Dave’s “Hold On, I’m Comin’,” but not on “It Ain’t No Fun to Me,” “In the Midnight Hour,” “In the Midnight Hour” is famous as a supposed example of a delayed backbeat (Bowman 1995, 308–309; Covach and Flory 2018, 235–236). But the analyses of Smialek (2020) and Hosken (2021) concur with ours that the snare in this recording does not have a consistent pattern of delay. One possible reason for the perception of backbeat delay in this track is the playing of the horn section on the backbeats, sounding slightly later than the snare hits. “Knock on Wood,” “Soul Man,” or “I Never Found a Girl.” As with the Stones recordings that show a strong tendency towards backbeat delay, recordings by other artists that have the highest average beat 2 delays still have relatively high standard deviations, reflecting how the exact amount of delay is highly variable even when there is a strong tendency towards playing behind the beat.

When comparing Watts’s practices with those of other drummers in the two full sets of data, it appears that Watts much more commonly delayed beat 2 at least 2.5 percent of mean IOI (Example 18). Overall, he substantially delayed the second beat 29 percent of the time, while other drummers did so only 15 percent of the time (p < .001). This holds true also when looking only at releases prior to 1979, a timeframe when both sets of data showed more consistent beat 2 delays (Example 16). Prior to 1979, Watts substantially delayed an average of 33 percent of his second beats (45 percent in the 1967–73 period) and other artists only substantially delayed 20 percent (p = .002). Watts delayed beat 4 approximately the same amount as beat 2, while other drummers on average showed no significant tendency to delay beat 4. The mean percentage delay of Watts’s second beats prior to 1979 was 1.4 percent (2.4 percent during 1967–73), while other drummers prior to 1979 had just 0.6 percent mean delay (p = .01). Watts also delayed backbeats more than other drummers when playing the same song. While Watts’s studio version of “Heart of Stone” substantially delays 25 percent of the second beats, beat 2 attacks in the Metamorphosis version of the song with substitute drummer Clem Cattini are on average slightly ahead of expectation. The Stones’ cover of “I’m a King Bee” substantially delays 50 percent of the second beats, while the original shows no statistically significant tendency towards beat 2 delay. Similarly, covers of Stones songs by Linda Ronstadt (“Tumbling Dice”) and Blackberry Smoke (“All Down the Line”) do not show the same propensity for delayed backbeats as the originals. After 1978, Watts continued to show a significantly greater tendency to delay beat 2 and beat 4 than other drummers, though with both corpora, the delays were smaller and less consistent from 1979 onwards. In fact, other drummers from 1979 and after show a slight tendency to anticipate both beat 2 and beat 4. Overall, there is significant evidence that Watts delayed backbeats to a greater degree and more frequently than his contemporaries, with the tendency particularly strong between 1967 and 1973, a period of time that nearly matches Jimmy Miller’s tenure as the Stones’ producer (1968–1973).

IV. Tempo Variability: Patterns

We turn now to tempo variability in the music of the Rolling Stones in order to further elucidate the reality behind the myths regarding Charlie Watts. After a brief discussion of prior scholarship and our methodology, we identify four primary models of tempo curve for the band’s music and closely examine tempo variability in two examples.

In classical music, tempo fluctuations such as ritardandi, accelerandi, and rubato are accepted as conventional musical elements. Tempo variability in performance of classical repertoire has been studied by multiple scholars, including Repp, who uses the term “timing microstructure” to refer to the “continuous modulations of the local tempo” that occur in classical performance, particularly in Romantic-era repertoire (1995, 40). Yet mainstream popular music in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, particularly that dating from after the start of the rock ‘n’ roll era in 1955, is generally assumed to have a steady tempo—even a metronomic approach. Human drumming without a metronome, however, involves small fluctuations in tempo that can act expressively, and commentators have argued that such fluctuations characterized Watts’s performances. Tempo fluctuations in Watts’s drumming occur within the context of the Rolling Stones as a band, so it is necessary to look at the band as a whole in this regard. Because one aspect is individual and the other is collective, one must be cautious in making direct comparisons between analysis of microtiming in Watts’s drumming and analysis of the tempo variability of the entire band. We nevertheless present analyses of drum microtiming and tempo variability side by side because they are so closely interrelated and together provide a more complete picture of Watts’s drumming.

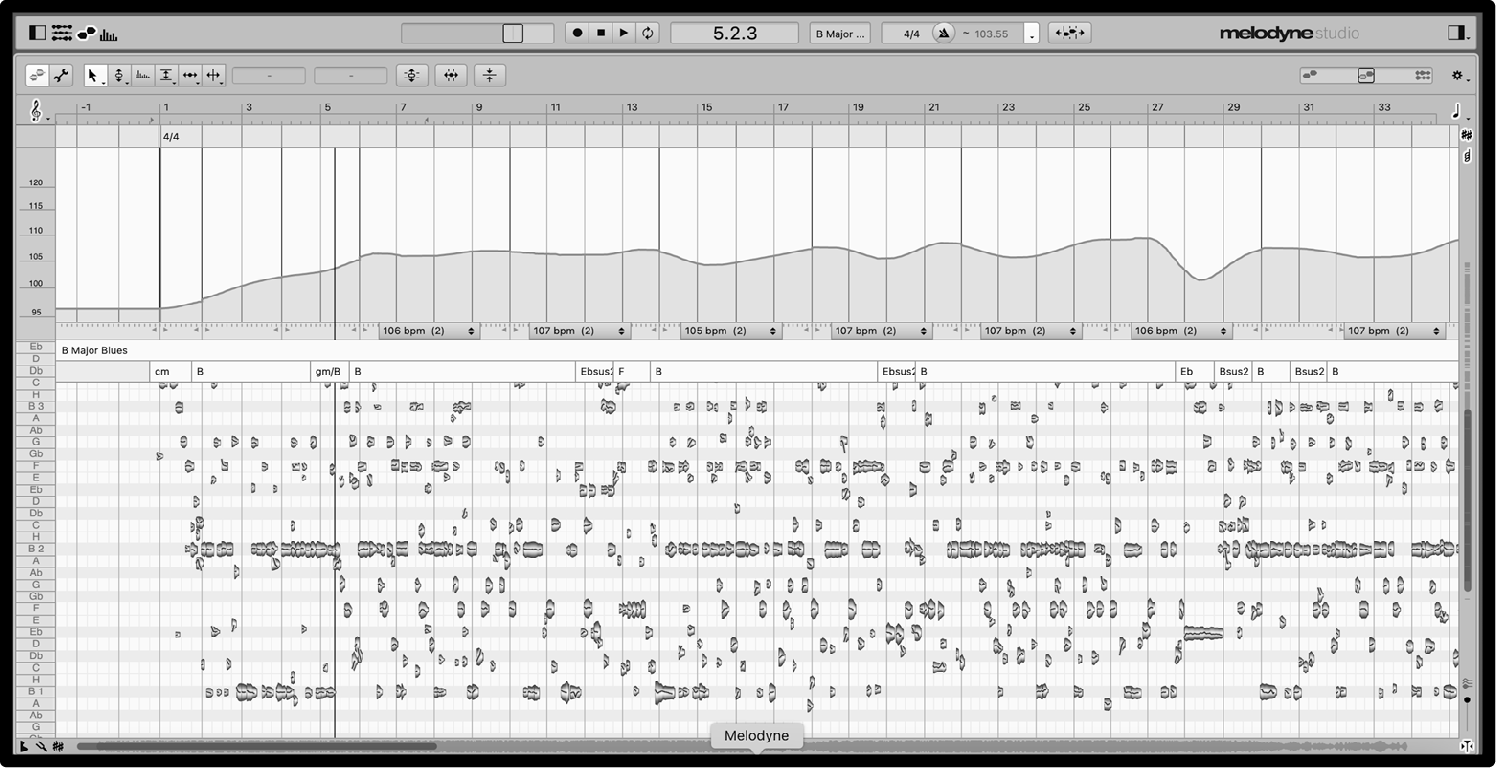

In order to better understand tempo variability in the playing of Watts and the Rolling Stones, we used Celemony’s Melodyne 5 Studio software to detect attack transients and automatically generate a tempo map showing the tempo at all points in a song (Example 19). Polfreman (2013) evaluated the ability of an earlier version of Melodyne to track attack transients, finding that it identified percussive attacks well but showed significant discrepancy from perceptual attack times for bowed sounds (4–5). This tempo map shows where the band speeds up or slows down and allows recognition of patterns. While these automatically generated tempo maps are mostly reliable, the algorithm can sometimes have difficulty staying with the beat when there are no drums playing or if there are ritardandi. Therefore, we listened to each song while looking at the tempo map and made corrections wherever necessary. In about half of the cases, it was necessary to manually enter the correct time signature, correct “octave” errors if the algorithm misinterpreted the tempo as being half or twice as fast (Schreiber 2020, 29), or make other manual adjustments. While another analyst might end up with slightly different tempo maps, this would not substantially affect the overall shapes described in this section. See footnote 33, below, regarding potential variability in tempo coefficient of variation calculations by different analysts using Melodyne. Looking at the shapes of 133 Stones studio recordings on which Charlie Watts played drums (Appendix Example 3; Example 20), we were able to identify four primary models for tempo variability.

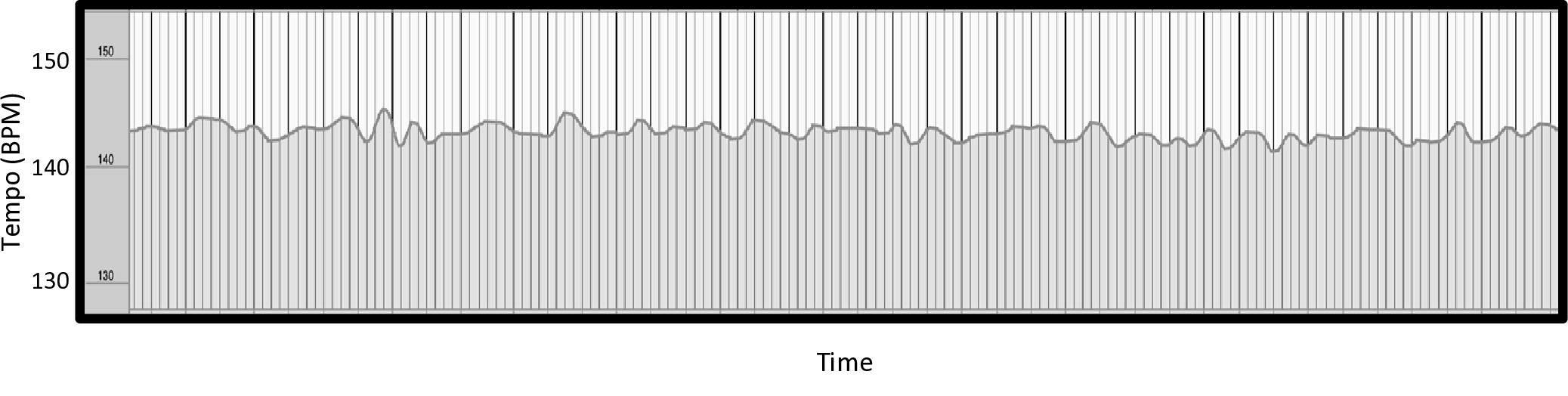

In the first model, the tempo is a relatively flat line (Example 21). There may be some small ups and downs, but the tempo stays within a relatively narrow range. This approach can be heard in the songs “Harlem Shuffle” (1986), “Mixed Emotions” (1989), and “Terrifying” (1989), though a relatively flat line is rare for the band, especially prior to the 1980s.

The second shape can be found more often in their ’60s and ’70s recordings: here the band significantly increases the tempo within the first handful of bars, then is relatively steady after that point. This pattern is heard in “Sweet Virginia” (Example 22), where the guitars start at 93 BPM and quickly reach 106 BPM within just 12 bars. This kind of early acceleration occurs also in “Stray Cat Blues,” “Dancing with Mr. D,” and in 1970s live versions of “Honky Tonk Women,” “Brown Sugar,” “Jumpin’ Jack Flash,” and “Tumbling Dice.” We observed early acceleration in other artists’ studio recordings as well, including in the Jimi Hendrix Experience’s “All Along the Watchtower” and Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Born on the Bayou.”

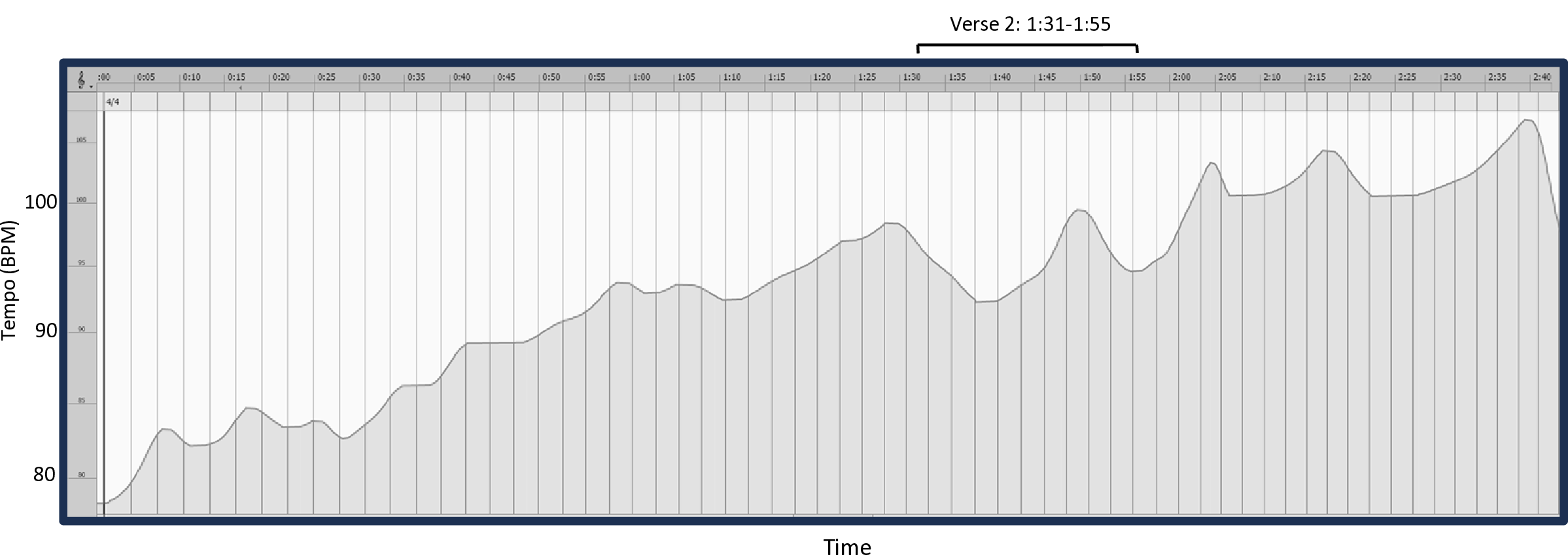

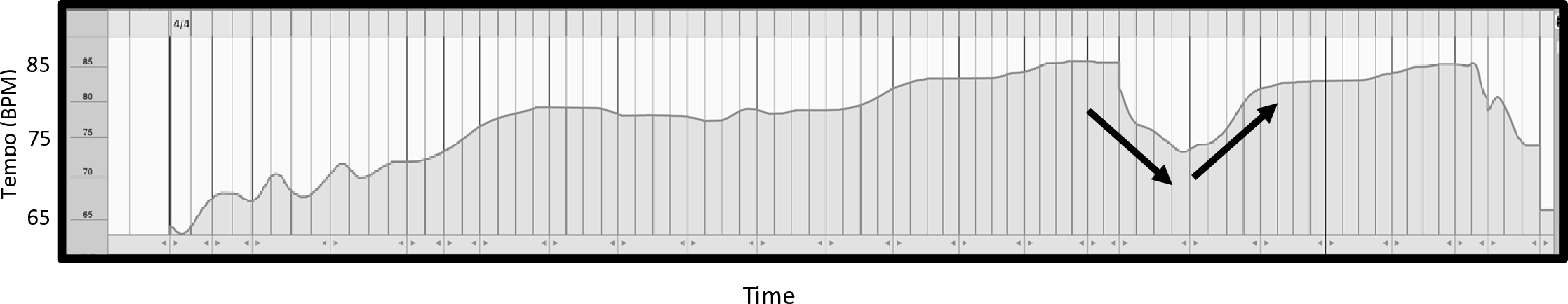

A third pattern found in Stones studio recordings from the 1960s and ’70s involves a continuous increase in tempo throughout a song. Examples include “Salt of the Earth,” “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” (on which Jimmy Miller substituted for Watts), “Honky Tonk Women,” and “You Got the Silver.” As shown in Example 23, “You Got the Silver” starts at 78 BPM and has an almost continuous acceleration until it reaches 107 BPM by the end, an increase of 37 percent. Such gradual accelerations are consistent with findings that a drift towards faster tempos is common in musical performances generally (Merker et al. 2009, 9). “Salt of the Earth” and “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” also illustrate how the building of instrumental texture is often associated with tempo acceleration, consistent with observations that greater loudness and fuller textures are associated with greater speed (e.g., Huron 2006, 323–324). Baur discusses the combination of increasing texture and tempo in “Salt of the Earth” (2020, 37–38). We did not find examples where the Stones significantly slowed down over the course of a song. Other artists also speed up much more commonly than they slow down, with accelerating examples including “I’m So Tired” by the Beatles, “Hells Bells” by AC/DC, and “Babies” by Pulp.

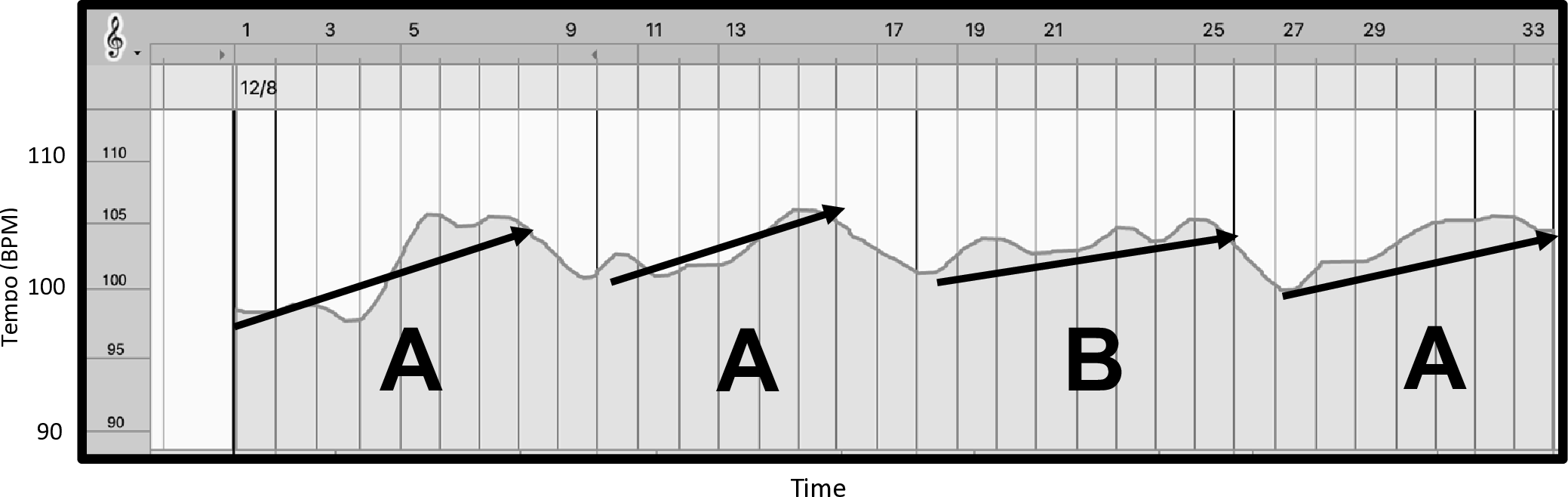

A fourth approach is for the tempo to vary according to the formal sections of the song. For instance, the band sometimes speeds up to the end of a verse and then slows down for the beginning of the next verse. This pattern may repeat several times throughout a song, especially with a series of 12-bar-blues strophes or with A sections in a 32-bar AABA form. Such sectional tendencies are reminiscent of those identified by Räsänen et al. in their study of Michael McDonald’s “I Keep Forgettin’” (2015, 7–8). Example 24 shows the Stones’ 1964 cover of Gene Allison’s “You Can Make It If You Try,” in which these sectional accelerations reinforce the formal structure of the song. In verse-chorus songs, an acceleration at the end of the verse is typically maintained in the chorus, with the tempo then coming back down for the start of the next verse, as in the Stones’ “Shine a Light” (on which Jimmy Miller took the place of Watts). Such accelerations at the ends of verses leading into choruses are examples of acceleration as anacrusis, building excitement as a structural point of arrival approaches. Bridges, on the other hand, can be significantly slower than surrounding sections. Examples include the bridges in “Rocks Off,” “Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby, Standing in the Shadow?,” and “Let’s Spend the Night Together.” In “Shine a Light” (Example 25), the tempo slows for a brief instrumental breakdown, then the texture and tempo rebuild to a climactic final chorus. Huron has noted the tendency of performers to accelerate as they approach a climactic moment (2006, 326).

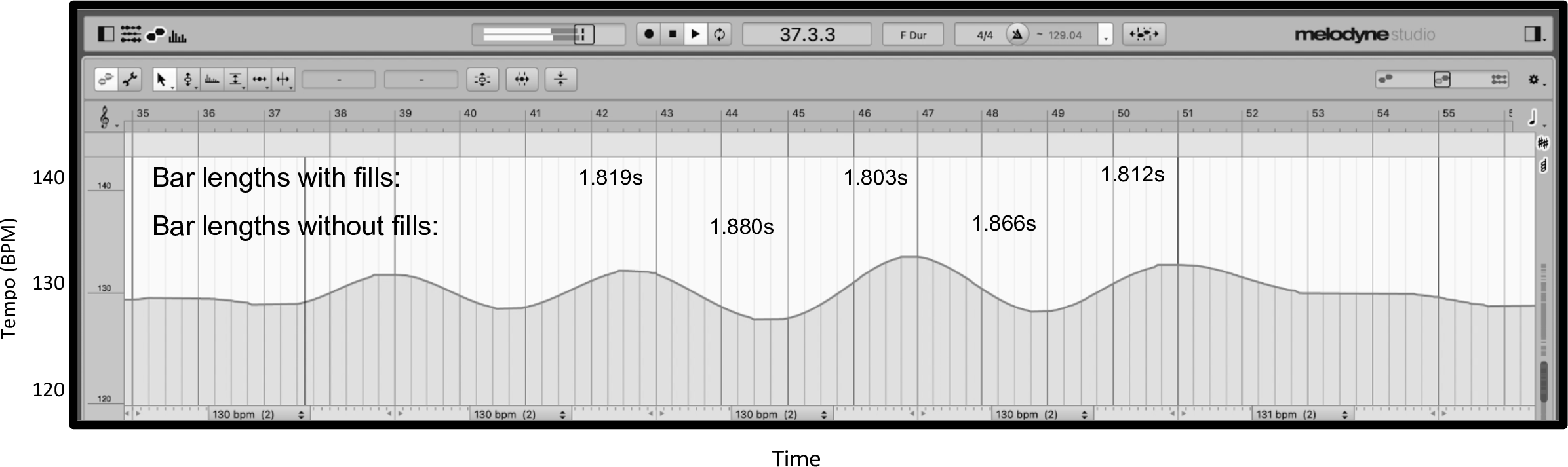

Apart from these four shapes, we can also observe tempo fluctuation on a more local level, from one bar to the next, when Watts plays a drum fill. Consistent with the tendencies of most drummers, he would slightly accelerate during his fills and then immediately return to a slower tempo, as can be heard in the 2004 live recording of “Start Me Up” from the Live Licks compilation (Example 26). This speeding up in preparation for a structural downbeat is another form of anacrustic acceleration (cf. Attas 2015, 289; Dodson 2011, 61). This is the opposite of what typically happens to tempo at the ends of classical music phrases (as well as in popular ballads), where it is more common to slow down as a cadence is approached (see, for example, Senn et al. 2012, 33).

Looking in greater detail at tempo variability in two Stones songs—“You Got the Silver” and “Monkey Man”—shows how larger-scale patterns of tempo change interact with more local variation. In “You Got the Silver” (Example 23), there is an almost constant pattern of acceleration tied to the building of texture, with one significant deceleration that interrupts this large-scale arc. This deceleration begins at 1:31, immediately after a slide electric guitar solo section featuring the full band. At this point Richards starts another verse, now accompanied only by an acoustic guitar. With the texture reduced, the tempo substantially slows. There is a local acceleration at 1:41 when an acoustic slide guitar joins the texture, and this acceleration continues when an electric slide guitar enters at 1:46, but the tempo begins to drop again at 1:50 when the texture is again reduced to a solo acoustic guitar. A more permanent, substantial acceleration only begins when the full band returns with a louder new verse at 1:55. This verse features not only the full slate of instruments but also Richards’s vocals an octave higher and reaches a tempo of 100 BPM for the first time at 2:02. The fastest tempo in the song (107 BPM) is achieved near its end, between 2:40 and 2:43, before a final, brief ritardando.

Another recording with a nearly continuous pattern of acceleration is “Monkey Man” (Example 27), a song whose microtiming we discussed in section III, above. The recording reflects interactions between tempo variability and microtiming deviations. From the perspective of tempo variability, the gradual increase from 91 to 110 BPM over the course of the song is essentially uninterrupted except for a significant structural drop in the second half and some rapid alternation near the very end (starting at 3:29). The area of decreased tempo runs from 2:32 to 3:25. It contains a slight gradual increase within it but represents a trough in the overall curve of the song. The start of this trough correlates with the start of the second portion of the instrumental break at 2:34, where the key changes from C♯ major to E major and a new chord loop of I–V–IV–V is used. The tempo drop and modulation also correlate with the second-most delayed beat 2 in the song, the first beat 2 after the modulation, which comes after a period of relatively consistent microtiming in the first portion of the instrumental break. Most of the area of decreased tempo occurs during the E major instrumental section; at 3:11, the key returns to C♯ major and Jagger starts a series of “I’m a monkey” exclamations as the tempo continues to accelerate. The closing (3:29 to the end) features wide tempo swings and sounds chaotic, with lots of drum fills, vocal improvisations, and all instruments very active.

V. Measuring Tempo Variability in the Rolling Stones

In addition to identifying patterns of tempo fluctuation in songs, we also developed a method to precisely measure tempo variability. Here, we discuss the method as well as our findings for both Watts and other artists.

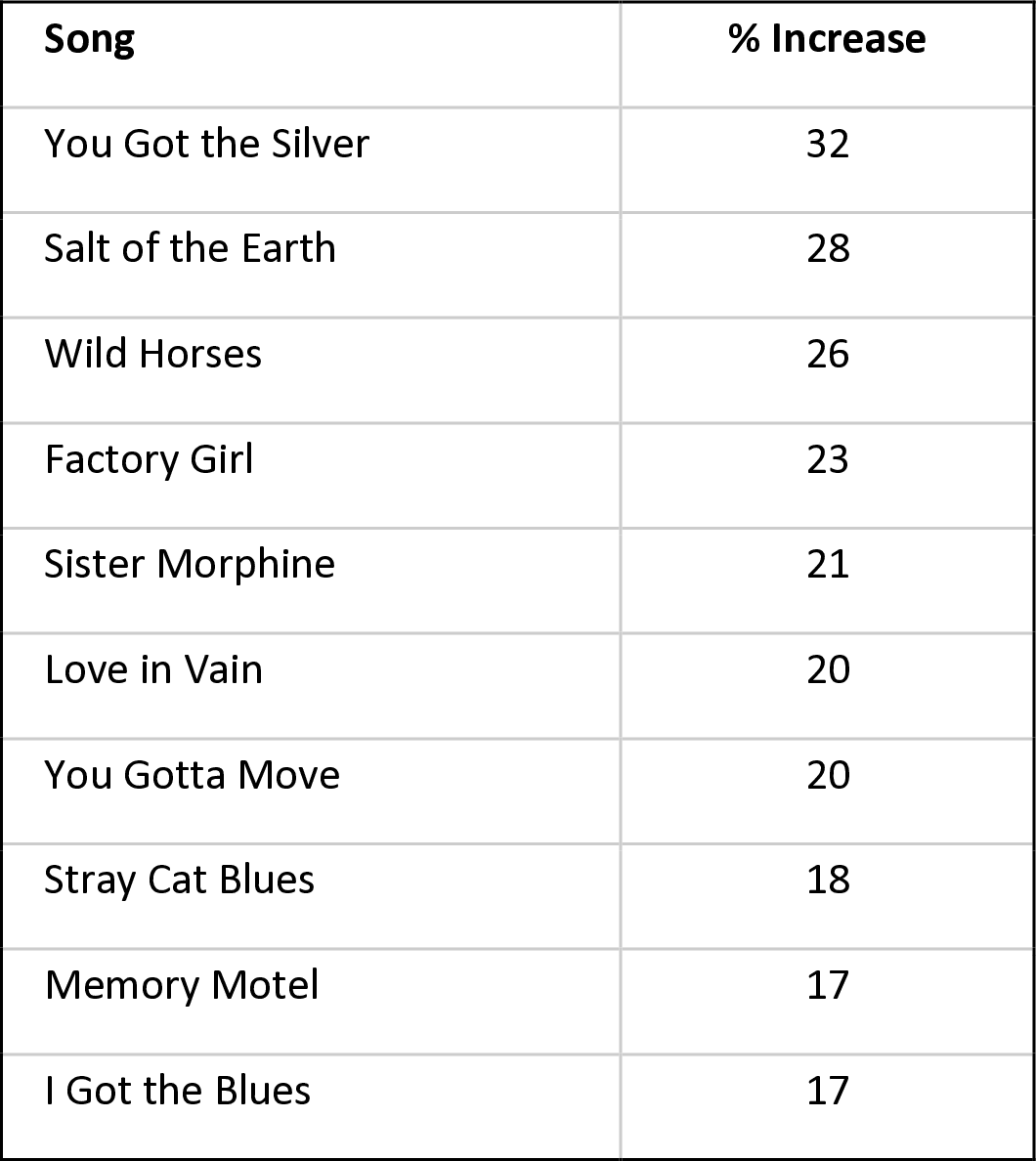

Building on the approaches to assessing tempo variability employed by Roessner (2017, 1–2), Schreiber (2020, 85–86, 118–119), and Condit-Schultz and Clark (2024, 4–5, 7–8), we used two methods to measure this aspect, one straightforward but limited, the other more sophisticated and nuanced. First, we used Melodyne to determine the difference between the tempos of the slowest and fastest parts of each song, calculating the song’s tempo range as a percentage of the slowest tempo in the song. Example 28 shows the Stones studio tracks with the largest percentage tempo increases as measured by this method. This approach provides an overview of the variability of the song, though it has limitations in the information it conveys because it does not indicate how much time is spent in the extremes or whether the variability is consistent or isolated.

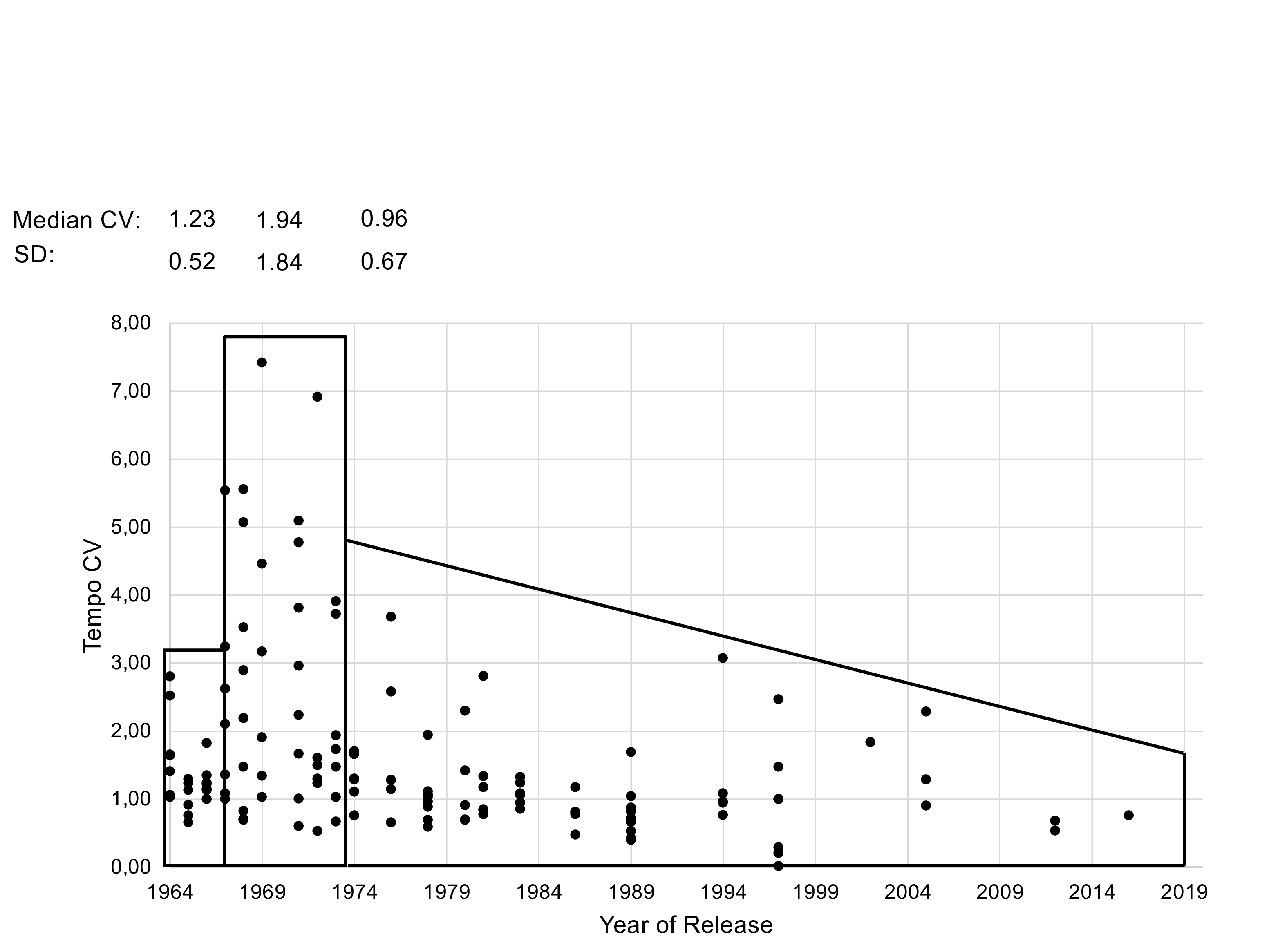

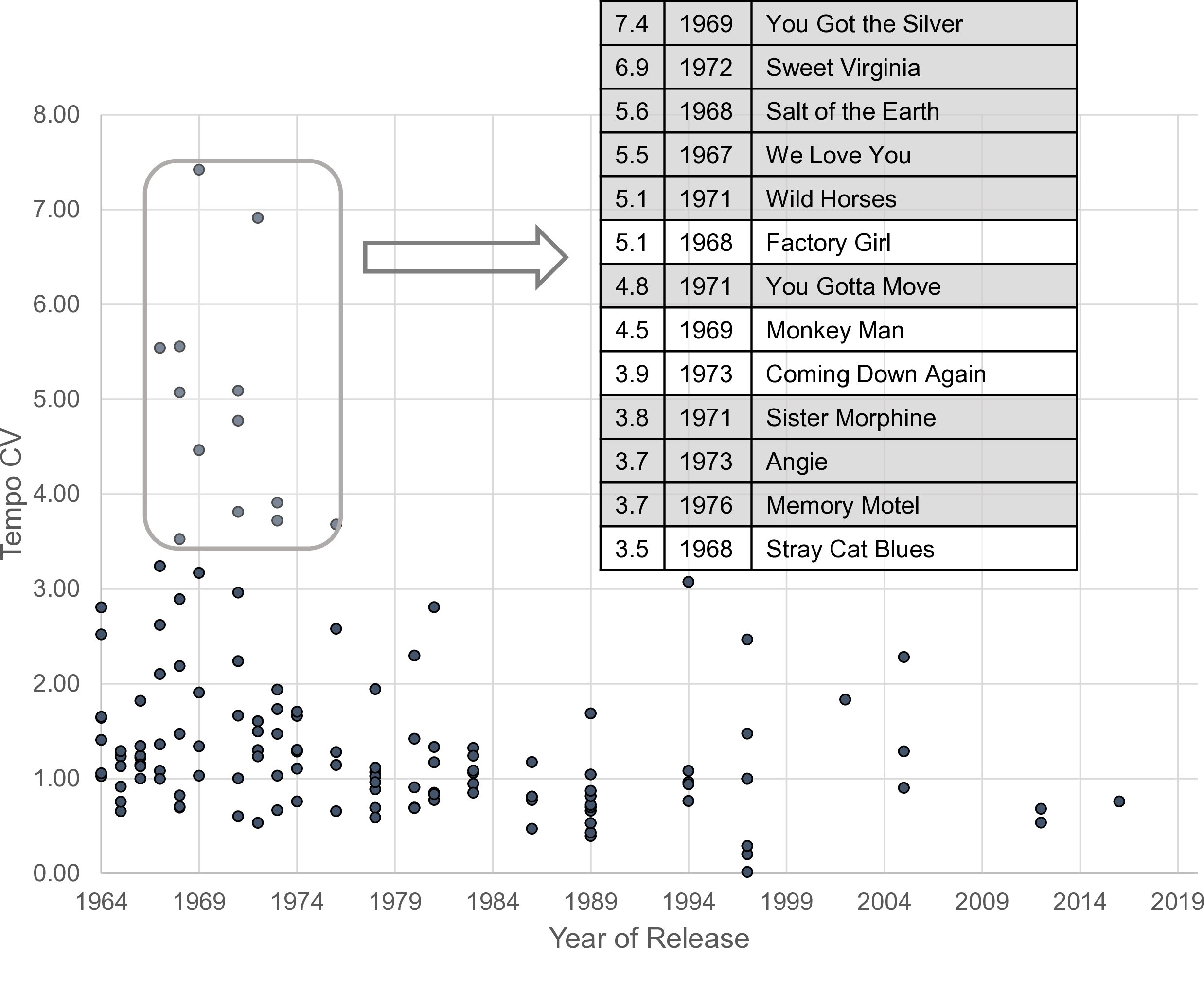

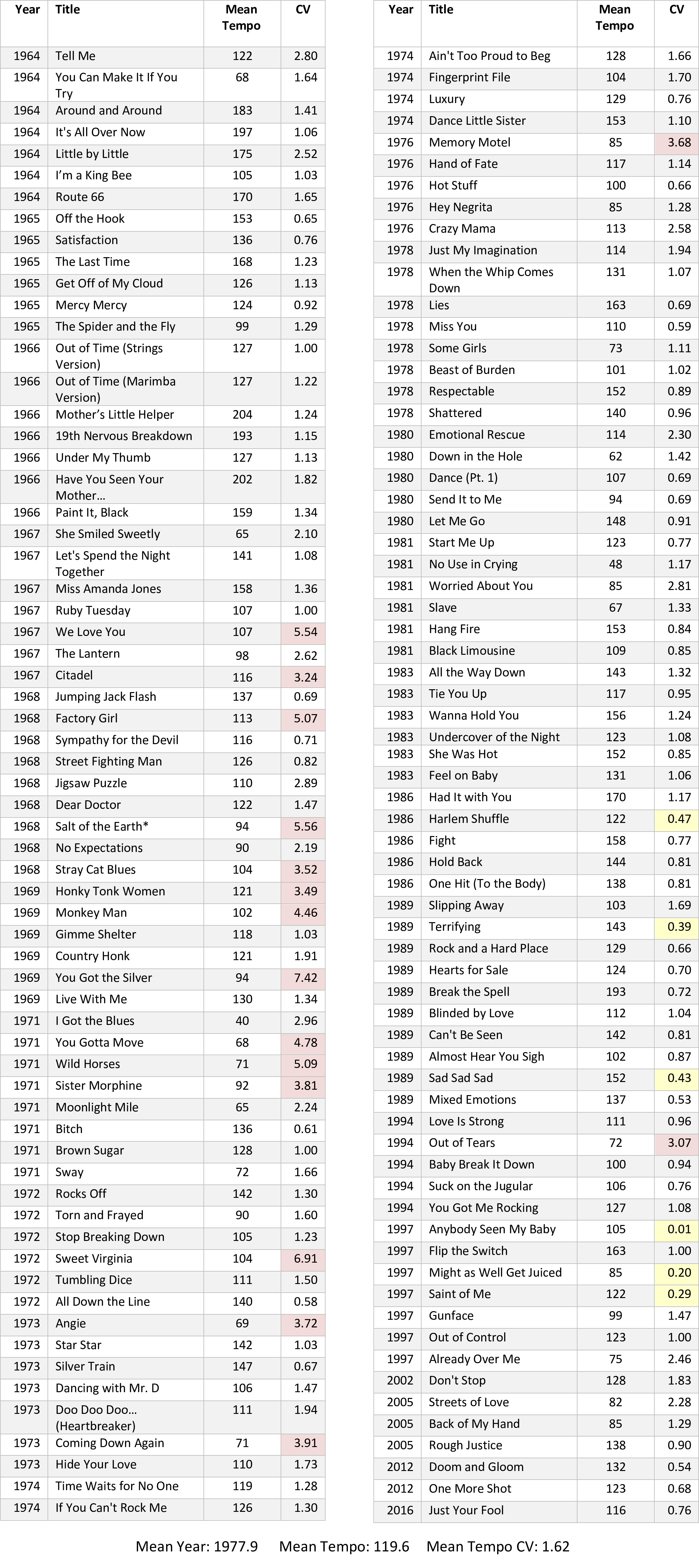

We therefore also used a method that determined the local tempos throughout the song, then assessed how much variability there was in these numbers over the course of the entire recording. We began by using Melodyne to generate a tempo map, as described in section IV, above. We then exported this tempo map as a MIDI file into Apple’s Logic Pro (a digital audio workstation) where it could be transformed into audio by turning on the metronome within the software. The metronome audio would then be bounced to an audio file that we imported into Sonic Visualiser. Within Sonic Visualiser, we used the BBC Rhythm: Onsets plugin to place a marker on each beat of the metronome, then exported this annotation layer as a CSV (comma-separated values) file into Excel. We used Excel to compute the local tempo of each set of two consecutive bars in the song, We used sets of two bars in order to approximate the window in which a listener perceives tempo. Schreiber points out that there is a lack of scholarly consensus on the timeframe within which tempo perception occurs. His approach is to use a 12-second window (2020, 115–117, 119). then calculated the standard deviation of these local tempo values. After determining the standard deviation of all local tempo measurements, we calculated the coefficient of variation, also known as the relative standard deviation. The coefficient of variation, or CV, is determined by dividing the standard deviation of the local tempo values by the mean tempo for the song, thereby allowing comparisons on the same scale of songs with different tempos. We multiplied this value by 100 in order to state it as a percentage. A CV of zero would indicate no change in tempo throughout the song. The Stones’ “Saint of Me,” for which Watts played along to a drum machine, has a CV of 0.29, while CV values of 2.0 or higher reflect a freer approach to tempo, with potential use of expressive rubato or clearly audible tempo changes (as in “You Got the Silver” [CV = 7.42] and “Sweet Virginia” [6.91]). There is potential variability in different analysts’ tempo CV calculations, even when our detailed method is followed, particularly in cases of songs with prominent ritardandi and/or caesuras. Analysis of the same tracks by different analysts suggests that analyses of songs with a CV of 1.0 or below will typically be identical or nearly identical, while independent analyses of recordings with tempo CVs greater than 1.0 can differ by up to 10 percent.

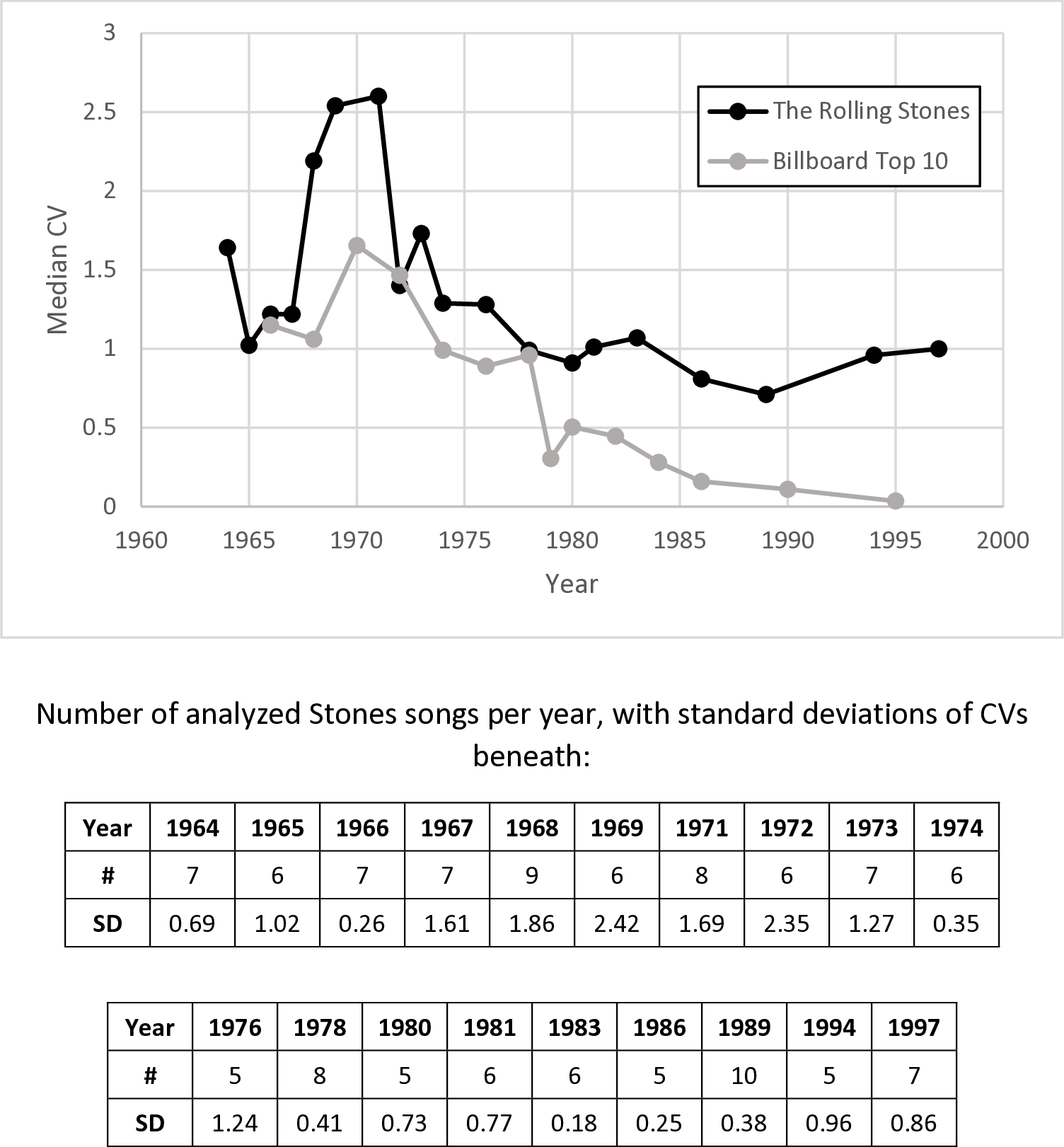

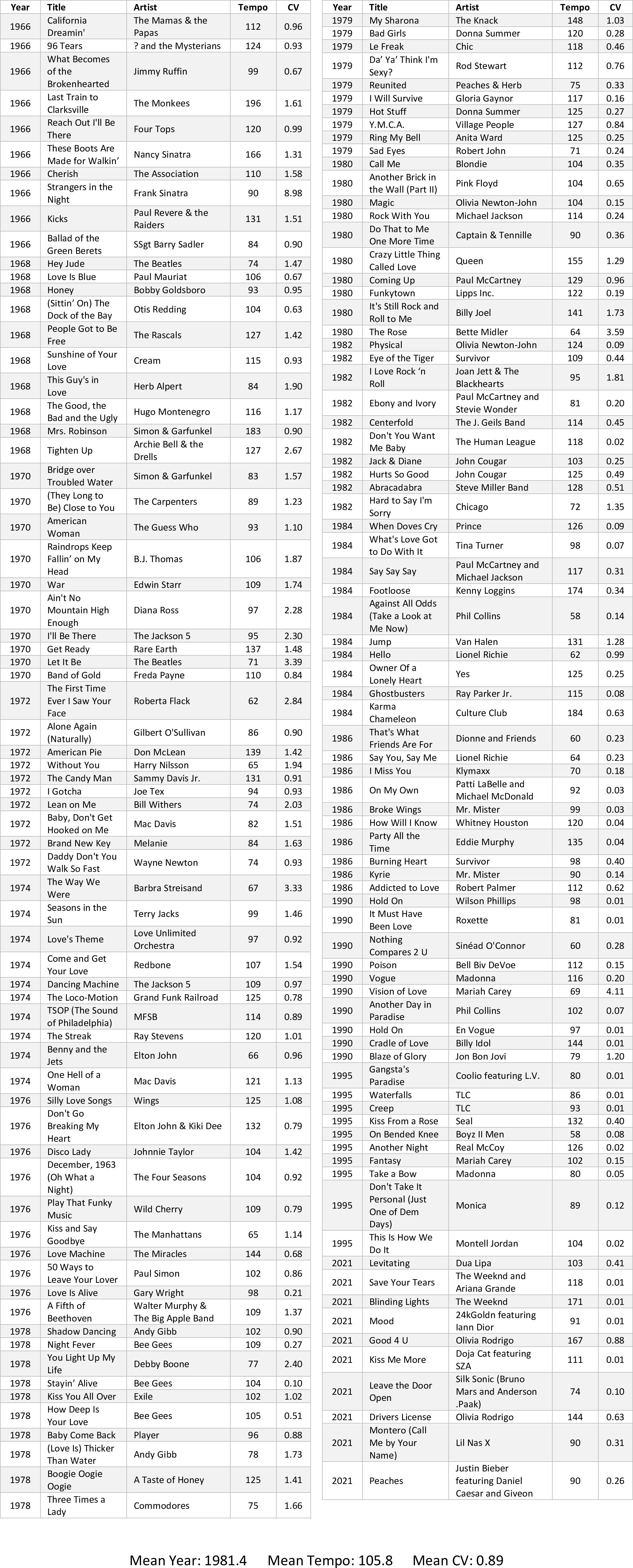

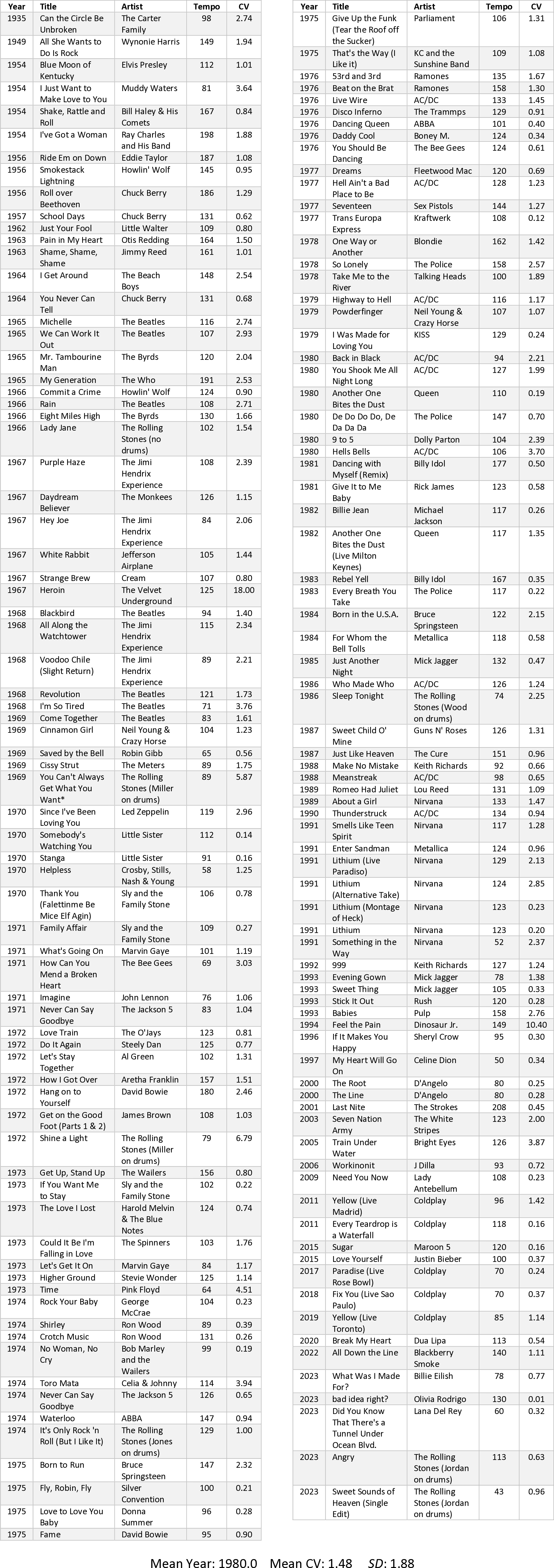

We calculated the tempo CV of 133 studio and 28 live recordings by the Rolling Stones as well as 304 recordings by other artists to compare them to, including the 10 biggest hits on the Billboard year-end charts for selected years between 1966 and 2021 (see Appendix Examples 3–5 and Example 34, below). We made a representative selection of studio recordings from each decade of the Stones’ career, as seen in Example 20, also selecting songs with a variety of different tempos and genres. The 28 live recordings were selected in order to get a mix of different chronological periods and tempos. We also analyzed multiple live performances of the same song in order to get an idea of how much tempo variability would vary by concert and decade. Besides the Billboard corpus, we selected 154 additional songs with other drummers that could be considered rough parallels in genre and time period to the songs in the Stones corpus, including seven Rolling Stones songs on which Watts was replaced by another drummer or otherwise did not play. The distribution of these songs by decade is seen in Example 29. This corpus also included some non-rock songs that were selected to help us better determine the ranges of CV values associated with the use of technological implements such as click tracks, loops, and drum machines.

Analysis of the Stones’ studio songs shows that the band’s career with Watts as drummer can be divided into three periods, based on the approach to tempo variability (Example 30; see also Example 35, below). In the first period, from the start of their career through early 1967, Watts and the Stones mostly maintained a steady tempo in their songs, though without metronomic precision. In this period, they often used tempo to delineate formal structure, so they might speed up slightly for a chorus but return to the original tempo for the next verse, consistent with the fourth tempo approach described in section IV, above.

The second period began with their August 1967 release of the single “We Love You.” 1967 was a transitional year for the Stones, in which they released two albums, Between the Buttons in January and Their Satanic Majesties Request in December. The tracks on Between the Buttons mostly have a steady tempo, while those from the self-produced psychedelic Their Satanic Majesties Request, such as “Citadel” (CV = 3.24), tend to have large tempo variability, with suite-like structures, fermatas, and rhythmically free sections lacking an isochronous pulse. The “We Love You” single and Their Satanic Majesties Request thus inaugurated a second period, running from mid-1967 to 1973, in which the Stones exhibited much more tempo variability in their studio recordings. After Their Satanic Majesties Request, from 1968 through 1973, when the band was produced by drummer Jimmy Miller and released some of their most celebrated albums, they showed a pronounced tendency to accelerate. Example 31 lists the Stones’ songs with the highest tempo CV values that we found for the band. All 13 of these songs are from the band’s Jimmy Miller period, the era in which they also showed the greatest penchant for delayed backbeats.

A third era for the Stones’ approach to tempo variability began in 1974. Starting with their self-produced album It’s Only Rock ‘n Roll, the Stones returned to keeping the tempo steady throughout their songs, but now with increasingly metronomic precision. The Stones’ median tempo CV returned to less than 1.3 in 1974 and remained under that upper limit for every analyzed year in the remainder of their career to date. Especially from 1980 onwards, the tempo CV in individual songs hardly ever rises above 1.0, with the only recordings over that threshold 1.0 being slower ballads. Of the 59 Rolling Stones studio recordings with Watts released subsequent to 1976 that we analyzed, only one—the maudlin 1994 ballad “Out of Tears”—had a CV over 3.0. The increased steadiness of Stones tracks released after 1976 correlates with their greatly reduced use of backbeat delay in the same period.

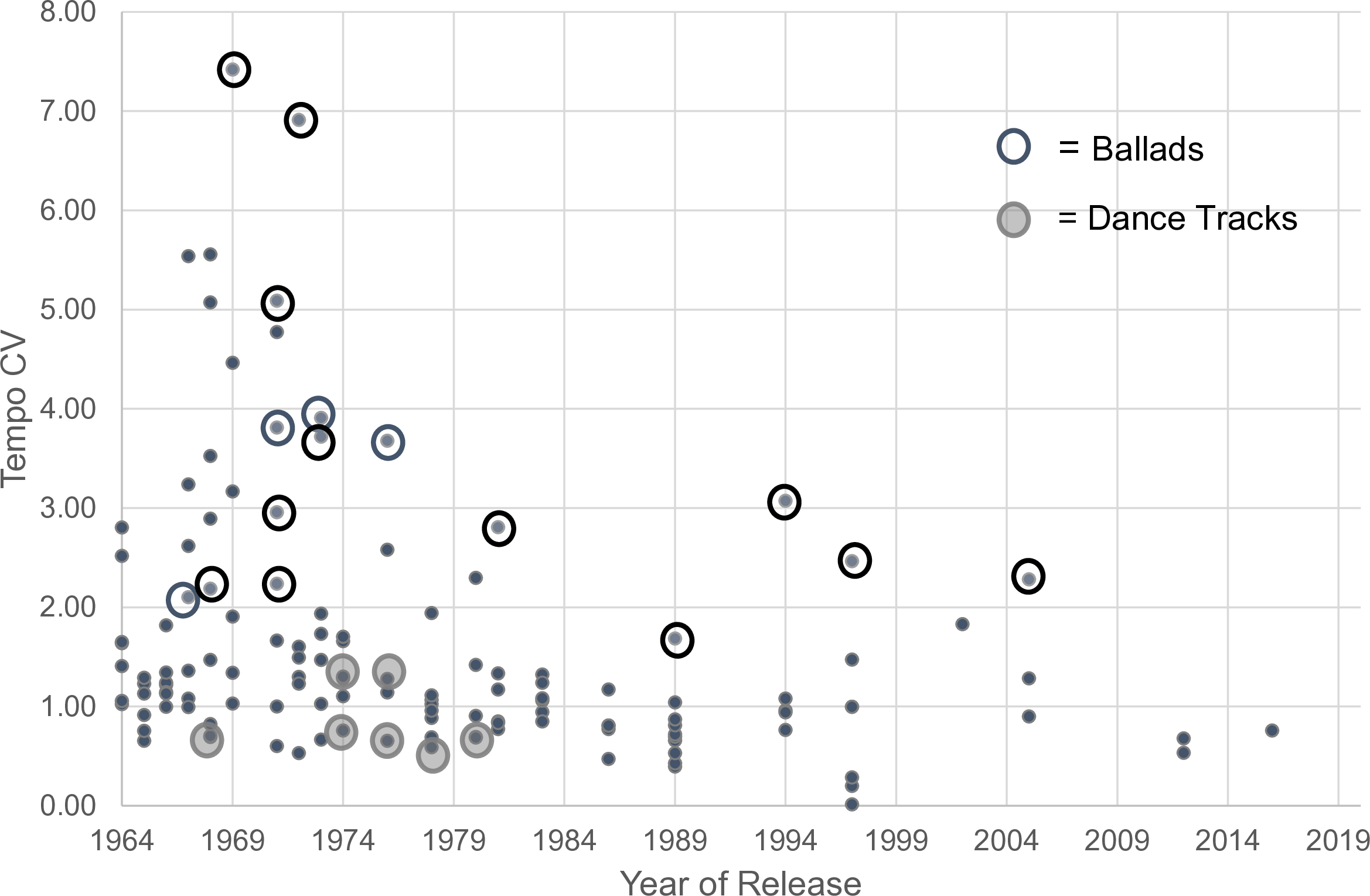

In addition to identifying these three periods of the Stones’ career, we noticed additional tendencies that apply to multiple eras. For instance, there appears to be a relationship between tempo variability and genre, just as there is with microtiming. The band tended to keep a relatively steady tempo in their Caribbean-, funk-, and disco-influenced songs. Examples include “Hot Stuff” (CV of 0.66), “Hey Negrita” (1.28), “Sympathy for the Devil” (0.71), and “Miss You” (0.59) (Example 32). The Stones’ ballads, on the other hand—such as “Memory Motel” (3.68), “Out of Tears” (3.07), and “Streets of Love” (2.28)—tended to significantly speed up and have relatively high CV values. This tendency in slower songs holds true throughout the Stones’ career as well as in the songs of other artists prior to 1980. Songs and passages without drums or percussion (in gray in Example 31) also tended to have greater tempo variability, a tendency especially apparent between 1968 and 1973.

Looking at tempo variability in Stones live recordings, Watts and the Stones showed a tendency to accelerate when performing. All 23 tracks on their live album El Mocambo 1977, for example, speed up at least a little (Example 33). But overall, the Stones displayed a similar mean tempo variability in their live recordings as in their studio recordings. We performed tempo CV analyses on 23 Stones live recordings on which Watts played drums (Example 34), spanning 1969 to 2015, and compared the mean tempo CV of these recordings with that of the studio recordings of the same songs. The mean CV was almost exactly the same, with the live versions having a mean of 2.01 and the studio versions of the same songs having a CV mean of 1.95 (p = .87). While many live versions displayed significantly more tempo variability than their studio counterparts (like “Tumbling Dice” and “Jumpin’ Jack Flash”), the reverse was also true—the studio recordings of “You Can’t Always Get What You Want,” “Route 66,” and “Monkey Man,” for example, have much more tempo variability than the live versions we analyzed.

Comparing the Rolling Stones’ tempo CV values in studio recordings with those of contemporaneous artists, Watts and the Stones overall showed substantially more tempo variability (mean CV = 1.62; 1964–2016) than the artists in the Billboard year-end Top 10 sample (mean CV = 0.89; 1966–2021; p < .001 for a two-sample t-test). The Stones’ mean CV was slightly higher but in a similar range as that of the non-Billboard Others corpus, which had a mean of 1.48 (1935–2023; p = .47). Example 35 shows that the Stones’ tempo CVs followed similar trends as the Billboard year-end Top 10 but reflected significantly more tempo variability. In the 1967–71 and 1980–95 periods in particular, the Stones showed much more tempo variability than the Billboard sample. The year with the greatest tempo variability in the Billboard corpus is 1970, with songs such as “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough,” “Let It Be,” and “I’ll Be There” contributing to a median tempo CV of 1.65. Similarly, 1969 and 1971 are the two years with greatest tempo variability for the Stones (they released no studio recordings in 1970), but their median values of 2.54 and 2.60 in these years are significantly higher than the 1970 Billboard median of 1.65. The median CV for corpus Stones recordings released between 1967 and 1971 was 2.22, while the Billboard corpus median CV value for 1968–70 was 1.43. The 1967–71 period includes Stones ballads with extremely high tempo CV values like “You Got the Silver” (7.42), “Wild Horses” (5.09), and “Sister Morphine” (3.81).

In the mid- to late 1970s both Rolling Stones and Billboard Top 10 tracks showed a decline in tempo variability as disco, funk, and reggae rose to prominence. Significantly, the Stones’ 1978 album Some Girls (0.99) had almost the exact same median tempo variability as the Billboard Top 10 that year (0.96), with the Stones on the album following contemporary trends towards disco in “Miss You” (their last U.S. number-one single) and punk with tracks like “When the Whip Comes Down” and “Lies.” But click tracks and drum machines rose to prominence in pop music in the late 1970s and early 1980s (Hesselink 2023, 124, 128–129), and the Stones for the most part did not follow suit. While the Billboard corpus median CV from 1979 on was 0.24, the Stones’ median CV in the same time period was 0.90—significantly lower than the 1.34 it had been before 1979, yet much greater than that of the Billboard Top 10 and well outside the range suggesting use of a click track. Songs in our Billboard and non-Billboard Others corpora known to have been recorded to a click track typically have CV values ranging between 0.2 and 0.5: for instance, Nirvana's “Lithium,” 0.20 (Coffman 2023); Sly & the Family Stone’s “Family Affair,” 0.27 (LeRoy 2023, 32); and Ron Wood's “Shirley,” 0.39 (LeRoy 2023, 38). It thus appears from the data that the Stones largely continued recording without a click even as click tracks, sequencing, and drum machines dominated the popular mainstream in the 1980s and ’90s. While the band with their 1986, 1989, and 1997 albums (Dirty Work, Steel Wheels, and Bridges to Babylon) showed a tendency towards lesser tempo variability as they tried out more modern approaches to recording and worked with hip-hop producers the Dust Brothers, among others, their CV numbers even in this period are not nearly as low as mainstream pop acts of the time. Example 36 shows their six songs with tempo CV values less than 0.5, all from these three albums. The low tempo CV measurements for the Stones tracks in Example 36 suggest the use of mechanical assistance, despite guitarist Keith Richards’s vocal disapproval of the use of “hi-tech stuff” in the studio (Mattingly 1990, 21). For 1997’s “Saint of Me,” one of three Dust Brothers-produced tracks in Example 36, Watts played over a recording of a Roland TR-808 drum machine (Janovitz 2013, 363–364). Since 1997, the Stones seem to have largely rejected the use of tempo assistance in recording, with their tempo CVs primarily ranging between 0.5 and 2.0. Nowadays, even with Steve Jordan having taken the late Watts’s place, critics notice the band’s flexible tempos as something rare in popular music, with New York Times critic Jon Pareles writing of the band’s 2023 Hackney Diamonds album: “The songs are unapologetically hand-played and organic, not quantized onto a computer grid; they speed up and slow down with a human pulse” (2023).

VI. Conclusion

Questions regarding whether Charlie Watts’s delayed backbeats had patterns of tempo variability or had a special “feel” that made him an outstanding drummer and a key contributor to the Rolling Stones’ sound have broader resonance for the analysis of music and how listeners mythologize musicians. Our findings suggest that there is some truth to the notion that Watts did subtle things in his drumming that had a significant impact on the sound of the band, but the extent to which these elements made him unique may have been exaggerated. Our study examining a corpus of 81 Rolling Stones recordings and 59 recordings by other artists suggests that Watts delayed backbeats more often than his contemporaries, particularly between 1967 and 1973, when he substantially delayed 45 percent of his second beats. Prior to 1979, Watts substantially delayed 33 percent of his second beats, while other drummers studied delayed only 20 percent. Over the entirety of his career, Watts delayed beat 4 approximately the same amount as beat 2, while other drummers showed no significant tendency to delay beat 4. With respect to tempo variability, we found four recurring patterns of tempo change within Rolling Stones songs. We also determined that while the Stones largely followed mainstream pop’s trends with regard to tempo variability over time, the band tended to accelerate and have greater tempo variability than mainstream pop, particularly in the 1967–71 and 1980–95 periods. The band’s median tempo coefficient of variation between 1967 and 1971 was 2.22, while the Billboard corpus median CV value for 1968–70 was 1.43. And from 1979 on, the Stones’ median CV was 0.90, while the Billboard corpus median was 0.24.

Backbeat delay and tempo variability are particularly associated with the genres embraced by the band between 1968 and 1973, a time when they were produced by Jimmy Miller and their music drew heavily from blues, R&B, soul, gospel, Americana, and country. It is therefore not surprising that this was the time in which we found the most significant evidence of backbeat delay and tempo variability. This era is often cited as the Stones’ “golden era,” when their recordings were most consistently successful from an artistic and commercial point of view, and part of this success may derive from their microtiming and tempo approaches. Despite dalliances with metronomic technology in the 1980s and ’90s, the Stones today can be heard as representatives of an earlier approach to tempo variability that had mostly disappeared from the popular mainstream by the twenty-first century.

It is important to note that, while Watts delayed backbeats in numerous songs, there are many recordings in which he did not use this approach, even during the time period when we found the most delayed backbeats. It is not clear whether Watts consciously changed his approach from song to song based on musical factors, whether changes in approach occurred accidentally, or some combination of these. It is also not clear to what extent backbeat delay or tempo variability on the scale we observed plays an important role in the “feel” or success of a track. The “feel” or “signature” of an individual drummer is the result of many factors besides microtiming and tempo variability, including the specific drumming equipment used and alterations to it, how the drums were recorded, dynamics, and the choice of drum patterns and fills. In addition, Watts’s playing occurred within the complex context of a five-person band (occasionally with additional musicians), and his contributions ultimately must be considered as part of that whole rather than in isolation. Given these factors, it is reasonable to suppose that many of the references to “delayed backbeats” and “playing in the pocket” that we encounter in tributes to Charlie Watts are a romanticization of an earlier generation of musicians and a distrust of technology. The Stones’ Keith Richards himself has lauded Watts’s ability to “innately” push and pull the tempo as an antidote to more modern recording practices: “It’s a bit of expression, instead of people looking at numbers and readouts. That doesn’t constitute rhythm; that just constitutes timing” (Mattingly 1990, 21).

Our research thus contributes to the conversation about “humanity” versus “automation” in music, both in the past and the present. The fact that Rolling Stones fans continue to vigorously debate in online forums whether the band has used click tracks shows the importance of these questions among listeners who view the Stones as icons of spontaneity and rebellion. By using objective methods to measure microtiming and tempo variability, we show that these discussions need not remain an echo chamber of competing rumors. Determining whether microtiming or tempo deviations have occurred will not end the debate over their value, but will allow listeners to better draw their own, more informed conclusions and listen to popular music with increased sensitivity to rhythmic nuance.

Appendix Examples

Works Cited

Attas, Robin. 2015. “Form as Process: The Buildup Introduction in Popular Music.” Music Theory Spectrum 37 (2): 275–296.

Bailes, Freya, Roger T. Dean, and Marcus T. Pearce. 2013. “Music Cognition as Mental Time Travel.” Scientific Reports 3 (1): 2690.

Baume, Chris. 2013. MIREX 2013 Onset Detection Submission: M4 Rhythmic Features. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=7d6b51bb9407e017616c3eae832348c0cd2af288.

Baur, Steven. 2020. “‘And the Drummer, He’s So Shattered . . .’: The Percussive Core of Beggars Banquet.” In Beggars Banquet and the Rolling Stones’ Rock and Roll Revolution, edited by Russell Reising, 26–40. New York: Routledge.

Beaumont-Thomas, Ben. 2021. “‘Not Just a Drummer—a Genre’: Stewart Copeland and Max Weinberg on Charlie Watts.” The Guardian, August 26. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2021/aug/26/stewart-copeland-max-weinberg-on-charlie-watts-rolling-stones#.

Benadon, Fernando. 2006. “Slicing the Beat: Jazz Eighth-Notes as Expressive Microrhythm.” Ethnomusicology 50 (1): 73–98.

Bowman, Rob. 1995. “The Stax Sound: A Musicological Analysis.” Popular Music 14 (3): 285–320.

Butterfield, Matthew W. 2006.(https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.06.12.4/mto.06.12.4.butterfield.php#AUTHORNOTE1) 2006. “The Power of Anacrusis: Engendered Feeling in Groove-Based Musics.” Music Theory Online 12 (4). https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.06.12.4/mto.06.12.4.butterfield.html.

Butterfield, Matthew W. 2007. “Response to Fernando Benadon.” Music Theory Online 13 (3). https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.07.13.3/mto.07.13.3.butterfield.html.

Butterfield, Matthew W. 2010. “Participatory Discrepancies and the Perception of Beats in Jazz.” Music Perception 27 (3): 157–176.

Câmara, Guilherme Schmidt. 2021. “Timing Is Everything . . . Or Is It? Investigating Timing and Sound Interactions in the Performance of Groove-Based Microrhythm.” PhD diss., University of Oslo.

Câmara, Guilherme Schmidt, Kristian Nymoen, Olivier Lartillot, and Anne Danielsen. “Timing Is Everything . . . Or Is It? Effects of Instructed Timing Style, Reference, and Pattern on Drum Kit Sound in Groove-Based Performance.” 2020. Music Perception 38 (1): 1–26.

Coffman, Tim. 2023. “The Classic Nirvana Song That Forced Dave Grohl to Use a Click Track.” Far Out Magazine, May 13.

Condit-Schultz, Nathaniel, and Beach Clark. 2024. “Have We Sold Our Souls to the Drum Machine? A Historical Analysis of Tempo Stability in Western Music Recordings.” Musicae Scientiae 28 (3): 451–477.

Covach, John, and Andrew Flory. 2018. What’s That Sound?: An Introduction to Rock and Its History. Fifth Edition. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Danielsen, Anne. 2006. Presence and Pleasure: The Funk Grooves of James Brown and Parliament. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.

Danielsen, Anne, Carl Haakon Waadeland, Henrik G. Sundt, and Maria AG Witek. 2015. “Effects of Instructed Timing and Tempo on Snare Drum Sound in Drum Kit Performance.” The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 138 (4): 2301–2316.

Danielsen, Anne, Kristian Nymoen, Evan Anderson, Guilherme Schmidt Câmara, Martin Torvik Langerød, Marc R. Thompson, and Justin London. 2019. “Where Is the Beat in That Note? Effects of Attack, Duration and Frequency on the Perceived Timing of Musical and Quasi-Musical Sounds.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 45: 402–418.

Davies, Matthew, Guy Madison, Pedro Silva, and Fabien Gouyon. 2012. “The Effect of Microtiming Deviations on the Perception of Groove in Short Rhythms.” Music Perception 30 (5): 497–510.

Dixon, Simon. 2001. “An Interactive Beat Tracking and Visualisation System.” In Proceedings of the International Computer Music Conference, Havana, Cuba: 215–218.

Dixon, Simon. 2007. “Evaluation of the Audio Beat Tracking System BeatRoot.” Journal of New Music Research 36 (1): 39–50.

Dodson, Alan. 2011. “Expressive Asynchrony in a Recording of Chopin’s Prelude No. 6 in B Minor by Vladimir de Pachmann.” Music Theory Spectrum 33 (1): 59–64.

Frane, Andrew V. 2017. “Swing Rhythm in Classic Drum Breaks from Hip-Hop’s Breakbeat Canon.” Music Perception 34 (3): 291–302.

Frane, Andrew V., and Ladan Shams. 2017. “Effects of Tempo, Swing Density, and Listener’s Drumming Experience, on Swing Detection Thresholds for Drum Rhythms.” The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 141 (6): 4200–4208.

Freeman, Peter, and Lachman Lacey. 2002. “Swing and Groove: Contextual Rhythmic Nuance in Live Performance.” In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Music Perception and Cognition, Sydney, edited by Catherine J. Stevens, Denis K. Burnham, Gary McPherson, Emery Schubert, and James Renwick, 548–550. Adelaide: Causal.

Friberg, Anders, and Johan Sundberg. 1995. “Time Discrimination in a Monotonic, Isochronous Sequence.” The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 98 (5): 2524–2531.

Hellmer, Kahl, and Guy Madison. 2015. “Quantifying Microtiming Patterning and Variability in Drum Kit Recordings: A Method and Some Data.” Music Perception 33 (2): 147–162.

Hennequin, Romain, Anis Khlif, Felix Voituret, and Manuel Moussallam. 2020. “Spleeter: A Fast and Efficient Music Source Separation Tool with Pre-Trained Models.” Journal of Open Source Software 5 (50): 2154.

Hepworth, David. 2021. “Charlie Watts’s Style of Playing Would Make Drum Machines Weep.” The Times, August 25. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/charlie-watts-tribute-the-sort-of-playing-that-would-make-drum-machines-weep-w3rkbcvgs.

Hesselink, Nathan. 2023. Finding the Beat: Entrainment, Rhythmic Play, and Social Meaning in Rock Music. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Hofmann, Alex, Brian C. Wesolowski, and Werner Goebl. 2017. “The Tight-Interlocked Rhythm Section: Production and Perception of Synchronisation in Jazz Trio Performance.” Journal of New Music Research 46 (4): 329–341.

Hosken, Fred. 2021. “Characterizing a Signature Metric ‘Feel’: The Stax Sound.” Presentation at the Society for Music Theory Annual Meeting, held online, November 4. https://osf.io/8apxs.

Hove, Michael J., Peter E. Keller, and Carol L. Krumhansl. 2007. “Sensorimotor Synchronization with Chords Containing Tone-Onset Asynchronies.” Perception & Psychophysics 69 (5): 699–708.

Huron, David. 2006. Sweet Anticipation: Music and the Psychology of Expectation. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Iyer, Vijay. 2002. “Embodied Mind, Situated Cognition, and Expressive Microtiming in African-American Music.” Music Perception 19 (3): 387–414.

Janovitz, Bill. 2013. Rocks Off: 50 Tracks that Tell the Story of the Rolling Stones. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Keil, Charles. 1987. “Participatory Discrepancies and the Power of Music.” Cultural Anthropology 2 (3): 275–283.

Kilchenmann, Lorenz, and Olivier Senn. 2015. “Microtiming in Swing and Funk Affects the Body Movement Behavior of Music Expert Listeners.” Frontiers in Psychology 6: 1232.

LeRoy, Dan. 2023. Dancing to the Drum Machine: How Electronic Percussion Conquered the World. New York: Bloomsbury.

Madison, Guy, and Björn Merker. 2002. “On the Limits of Anisochrony in Pulse Attribution.” Psychological Research 66: 201–207.

Madison, Guy, and Björn Merker. 2004. “Human Sensorimotor Tracking of Continuous Subliminal Deviations from Isochrony.” Neuroscience Letters 370 (1): 69–73.

Madison, Guy, Fabien Gouyon, Fredrik Ullén, and Kalle Hörnström. 2011. “Modeling the Tendency for Music to Induce Movement in Humans: First Correlations with Low-Level Audio Descriptors Across Music Genres.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 37 (5): 1578.

Mattingly, Rick. 1990. “Charlie Watts.” Modern Drummer, February.

McCormick, Neil. 2012. “Rolling Stones: One More Shot, Review.” The Telegraph, November 8. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/music/rolling-stones/9663741/Rolling-Stones-One-More-Shot-review.html.

Merker, Bjorn H., Guy S. Madison, and Patricia Eckerdal. 2009. “On the Role and Origin of Isochrony in Human Rhythmic Entrainment.” Cortex 45 (1): 4–17.

Miller, William F. 1994. “John Robinson: Going for the Throat.” Modern Drummer, November.

Nelias, Corentin, Eva Marit Sturm, Thorsten Albrecht, York Hagmayer, and Theo Geisel. 2022. “Downbeat Delays Are a Key Component of Swing in Jazz.” Communications Physics 5 (1): 237.

Pang, Keagan. 2019. “Deezer’s Spleeter: Deconstructing Music with AI.” Digital Innovation and Transformation: MBA Student Perspectives. Harvard Business School, November 25. https://d3.harvard.edu/platform-digit/submission/deezers-spleeter-deconstructing-music-with-ai/.

Pareles, Jon. 2023. “The Rolling Stones on Starting Up Again.” The New York Times, September 14. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/14/arts/music/rolling-stones-hackney-diamonds.html.

Polfreman, Richard. 2013. “Comparing Onset Detection & Perceptual Attack Time.” In Proceedings of the 14th International Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference (ISMIR 2013), edited by Alceu de Souza Britto Junior, Fabien Gouyon, and Simon Dixon, 523–8. Curitiba: International Society for Music Information Retrieval.