In an article recently published in this journal, I surveyed Osmin’s arias from Die Entführung aus dem Serail to demonstrate the ways in which Mozart used dramaturgically irregular phrase structures and text-setting to support that prickly caretaker’s recurrent bouts of discomposure (Bastone Barrettara 2022–2023). I also proposed that Osmin’s three solo numbers formed the nucleus of a network that could be expanded to encompass arias of similar character types, musical makeup, and dramatic circumstance, and that the network thus enlarged could be probed to reveal more about the dramaturgic implications of Mozart’s phrasing and rhythm. I borrow the “aria network” concept from Webster (1991).

This essay begins the expansion and exploration of that network with the arias of two other Singspiel servants: the like-named Osmin’s “Wer hungrig bei der Tafel sitzt” (Zaide, 1779–1780) and Monostatos’s “Alles fühlt der Liebe Freude” (Die Zauberflöte, 1791). As the German-language strophic offerings of secondary characters whose texts bespeak, albeit in different ways, the cultural confrontations of their East-meets-West Singspiels, these arias make for obvious first additions to Osmin’s network. The following analyses do not presume a lineage of Mozart’s dramaturgic techniques; rather, they simply explore how Mozart used text-setting and phrase structure as dramaturgic components of similar characterizations in similar musico-dramatic environments. In “Wer hungrig,” two different barring styles complement Osmin’s juxtaposition of sensible self-gratification and nonsensical self-denial; in “Alles fühlt,” a pattern-avoidant phrase structure exudes the frenzy of Monostatos’s desperation. Both arias recall, in different ways and to different degrees, the text-rhythmic and metric idiosyncrasies that I previously identified in the arias of the Entführung Osmin (Bastone Barrettara 2022–2023).

"Wer hungrig bei der Tafel sitzt"

A brief terminological review will help prepare the reader for the analysis ahead. For the first three quarters of the eighteenth century, theorists held sacrosanct that cadences should fall on strong beats. In 4/4, specifically, the first and third beats proved equally suitable, since those beat locations were considered equally strong. But in the century’s closing decades, German musicians began to reevaluate the anatomy of the 4/4 measure, newly asserting that the third beat was actually weaker than the first. For an expert account of this reevaluation and the nuanced views of the theorists who undertook it (including Kirnberger, Vogler, and Türk), see Rothstein (2008). On the eighteenth-century compound measure, see Grave (1985). This recalibration held major implications for text-setting. In settings of Italian text, the accento comune—the penultimate, most heavily accented syllable of a poetic line, for which only the most heavily accented musical beats were appropriate—was now confined to the downbeat, ensuring the convergence of the strongest syllable with the strongest beat (and oftentimes, a cadence). On the accento comune and Italian prosody, see Rothstein (2011, 92–93); on setting the accento comune in the eighteenth century, see Rothstein (2008, 122–23); on Mozart’s Italian text-setting, specifically, see Webster (1991, 133–37). In settings of German text, however, the lack of the accento comune allowed composers to entertain more flexible settings that privileged textual meaning over prosodic or cadential structure. End-accented phrases were not compulsory; mid-measure cadences (on beat 3) were not foul play. By 1800, German-language settings routinely cadenced mid-measure in all of the meters in which the second half of the bar could be subordinate to the first (commonly 4/4, 6/8, and 12/8). As we will see, this newfound latitude was especially handy for setting iambic tetrameter, a verse type so ubiquitous in eighteenth-century German libretti that Friedrich Lippmann called it the “beliebtesten deutschen Verse” (1978, 129). (Italian poetry shares no correlate type.)

In identifying this metric reconceptualization and its consequent national divergences, William Rothstein codified three styles of barring (2008, 116): “Italian” (comprising upbeats of a half-measure or longer and with downbeat cadences occurring more frequently than not); “neutral” (comprising a short upbeat, or none at all, with downbeat cadences); and “German” (comprising a short upbeat, or none at all, with weak-beat cadences). Rothstein contends that by recognizing these barring types, we may beneficially encourage or discourage certain interpretive choices, whether as analysts, listeners, or performers (150). I agree, and I would further argue that barring styles can assume dramatic functions that may influence the way we understand the semantic meaning of a texted work. The potential for such expression seems especially ripe in German-language music of the late eighteenth century, which benefitted from an increasingly pliable and nuanced approach to text-setting. In what follows, I will propose that there is a dramaturgically motivated shift from Italian to neutral barring in each verse of Osmin’s aria.

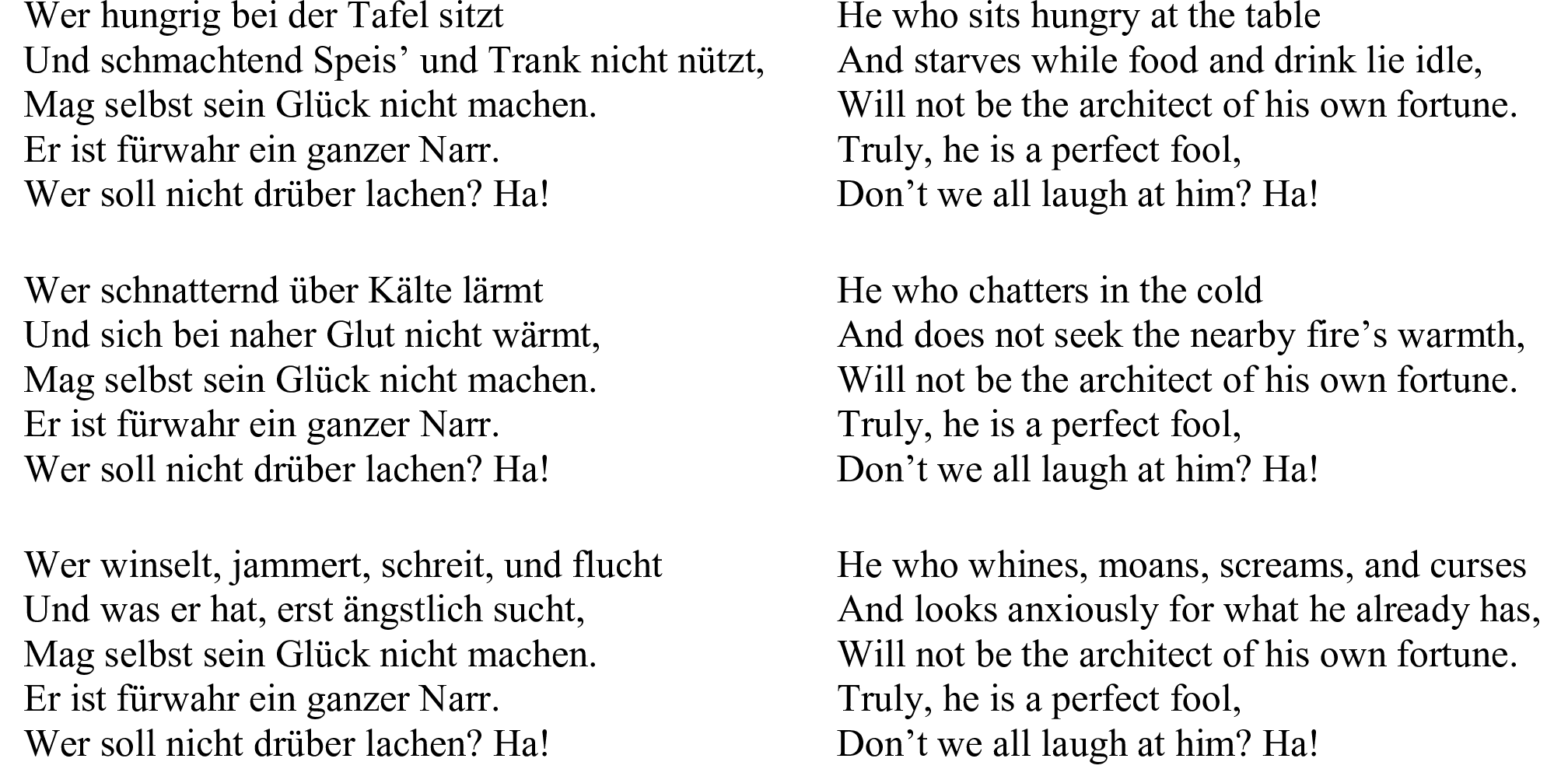

Mozart began intermittent work on Zaide in Salzburg in 1779. Extant from his unfinished score, which he abandoned to compose Idomeneo and the Entführung, are the first two acts; lost are all designs for the third and all of the dialogue. Like many Turkish operas of the time (including the Entführung), the plot of Zaide concerns two Europeans held captive in an Oriental harem and counts among its personage an overseer named Osmin who humorously shows little patience for his sultan’s Western vulnerabilities. For a full reconstruction of the plot, see Berke (2003). Osmin offers his only aria, “Wer hungrig bei der Tafel sitzt,” near the close of Act 2, after Sultan Soliman bemoans his unrequited affection for Zaide. Osmin derides the Sultan’s monogamous inclinations, boldly proclaiming through a metaphoric text that only an abstemious fool would forgo a harem brimming with women to gain the love of just one. The aria is in F major, 6/8 time, and marked Allegro assai; its text and translation are provided with an outline of its varied strophic form in Examples 1a and 1b.

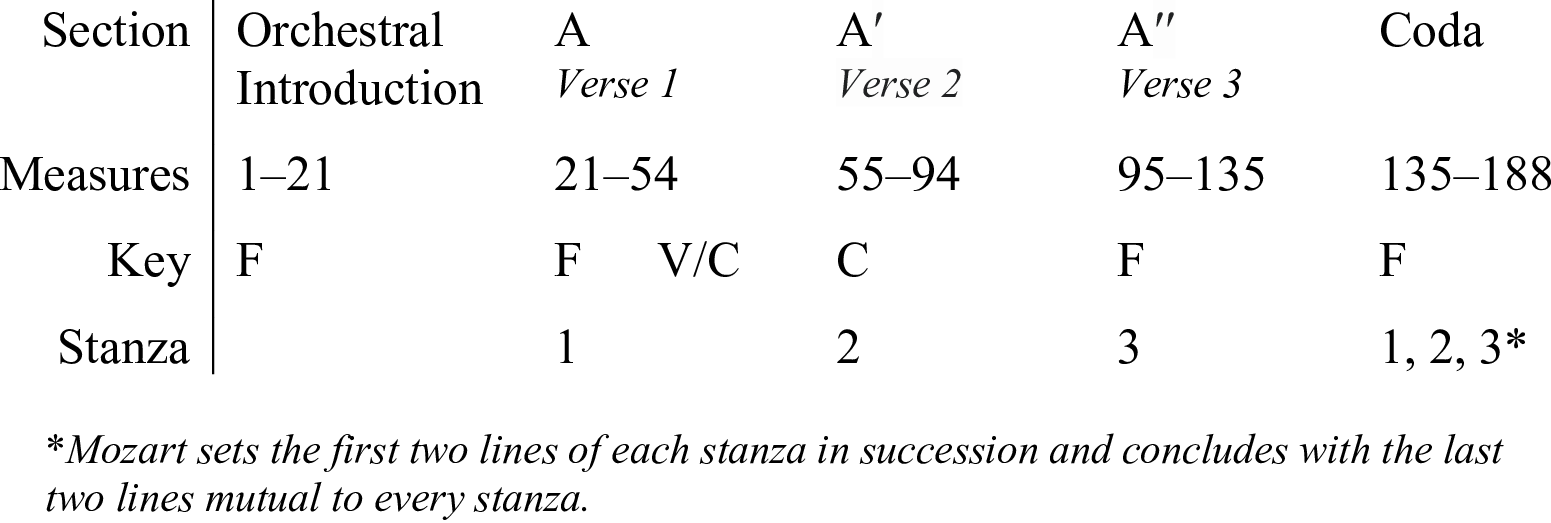

Each of the three five-line stanzas comprises two (sometimes rhyming) couplets of iambic tetrameter separated by a line of iambic trimeter. A line of iambic tetrameter contains four iambs (each containing an unaccented syllable followed by an accented syllable). A line of iambic trimeter contains three. (Recall from above that iambic tetrameter was the predominant verse type of late-eighteenth-century Singspiel libretti.) Mozart sets the first four lines of each stanza using the same sequence of rhythmic profiles across every verse. Rhythmic profiles are the rhythmic patterns suitable for each verse type owing to their arrangements of stressed and unstressed beats; see Webster (1991) and Lippmann (1978). He also sets the fifth and final line, the same in all three stanzas, with the same profile throughout, but variously casts its final syllable (“Ha!”) in phrase extensions that emulate a mocking laughter. This being the case, the first verse, which is provided in Example 2, can represent all three for the purposes of this text-setting analysis. For the sake of space, the orchestral introduction and coda will not receive special attention here. The introduction previews the rhythmic profiles of the first three vocal phrases of each verse; the coda recycles vocal phrases from the verses, respecting the order in which they were first presented. Brackets above the staff in the example delineate the aria’s regular quadruple hypermeasures, the discussion of which I will reserve for the conclusion of this study.

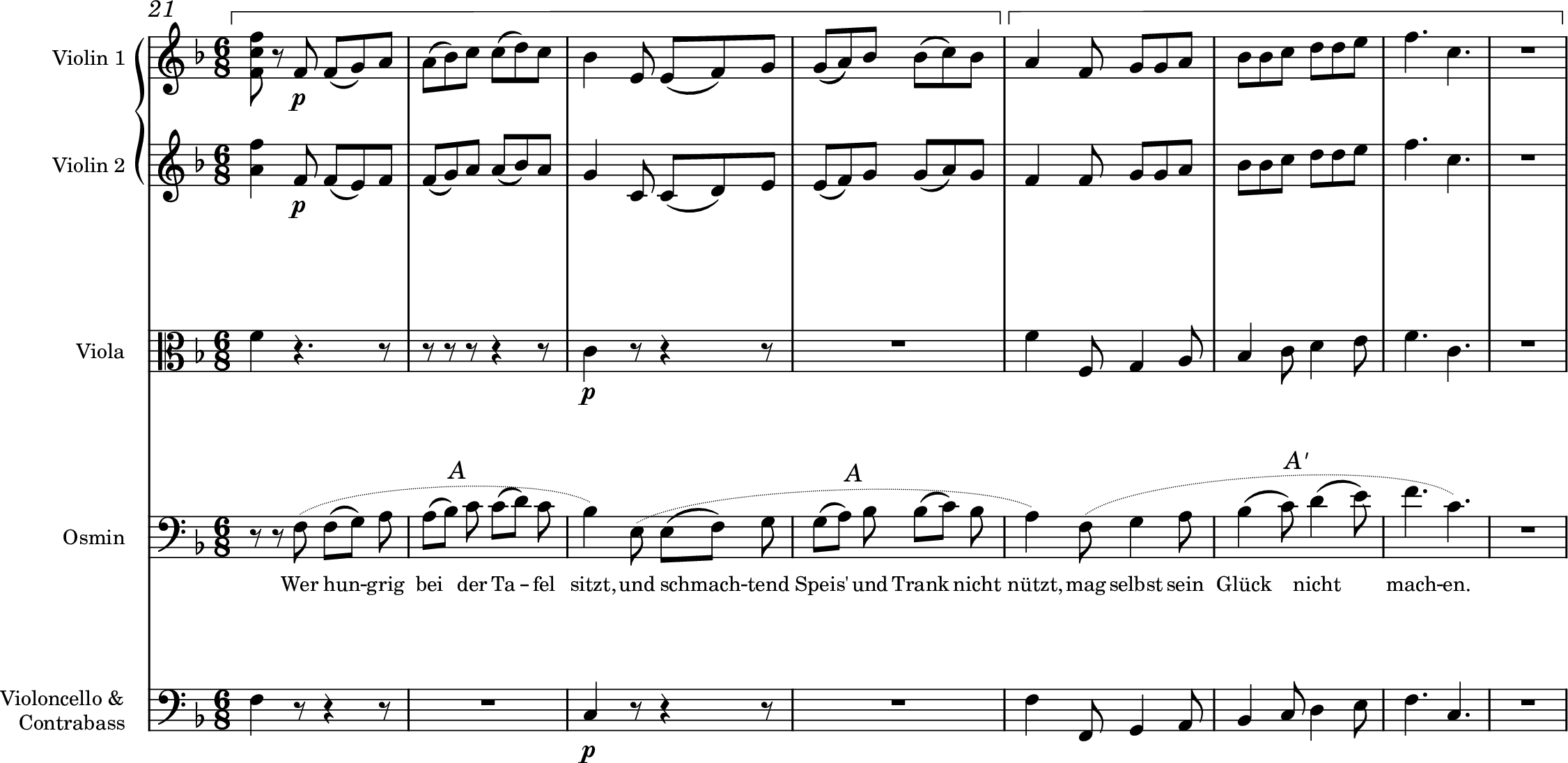

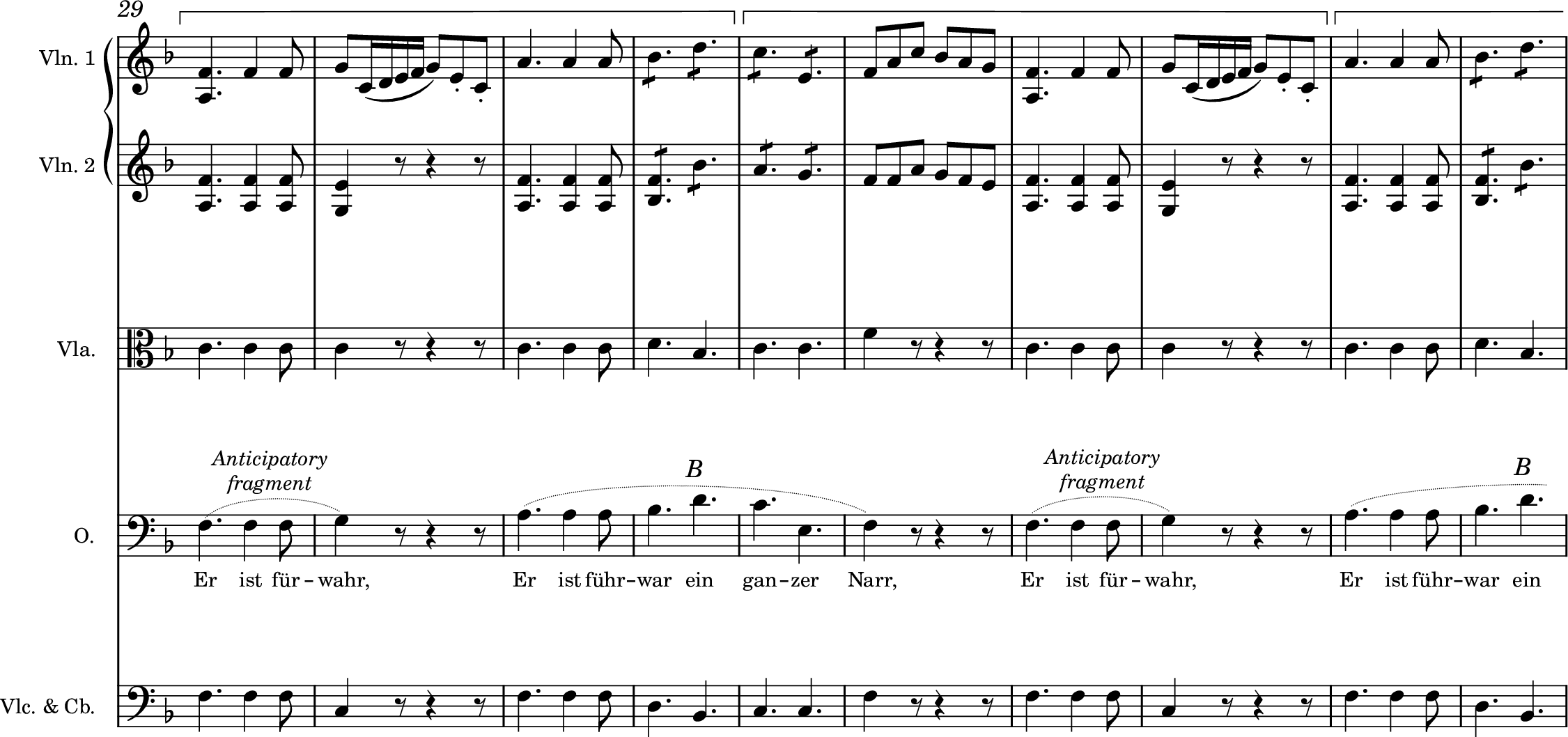

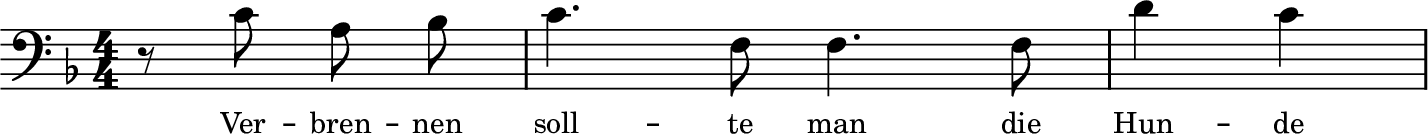

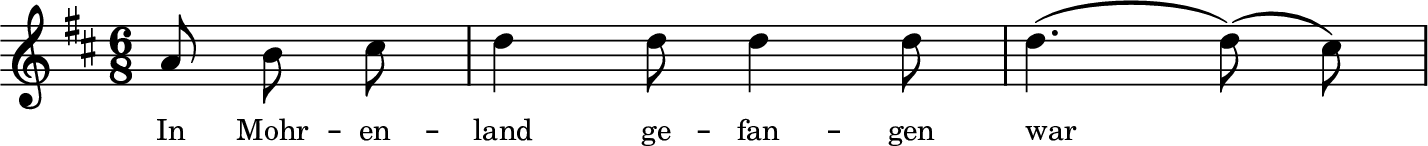

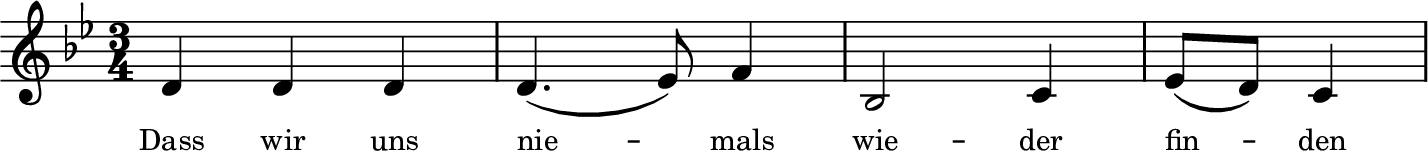

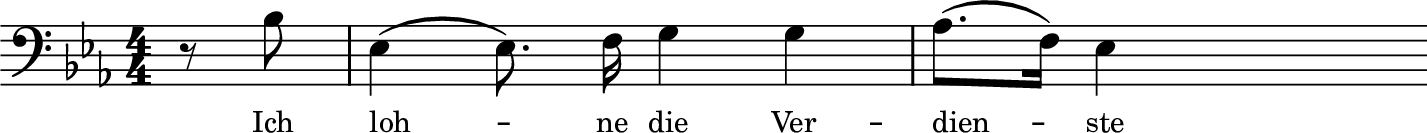

The first two lines of text are set in two vocal phrases, which Mozart bars in the Italian manner. As in my article on the Entführung Osmin (Bastone Barrettara 2022–2023), the term “vocal phrase” refers to a melodic segment circumscribed primarily by the poetic text and the pauses necessitated by the singer’s breathing and secondarily by melodic, harmonic, and cadential rhythmic content. Because Mozart uses the same rhythmic profile for each phrase, both are labeled “A” in Example 2. The first phrase begins in m. 21 with an extended upbeat that places the first textual stress on the second accented beat of the 6/8 measure and concludes with the fourth textual stress on the downbeat of m. 23; the second phrase proceeds with the same distribution across mm. 23–25. The third vocal phrase sets the stanza’s only line of iambic trimeter using a similar rhythmic profile; labeled “A′,” it begins with the same upbeat (m. 25) as had the previous phrases, but it concludes mid-measure with an unaccented syllable (m. 27). Mozart rarely wrote such extended upbeats when setting iambic verse. On this rarity and Mozart’s iambic habits (especially as pertains to my discussion of Example 3), see Lippmann (1978), Schmid (2003), and Bastone (2017). For lines of iambic tetrameter, especially in Zaide and the Entführung, he typically began with: (1) a single upbeat eighth or quarter note (as shown in Examples 3a–b); (2) a three-note pickup that prioritizes the strong fourth syllable with downbeat placement (Examples 3c–e); or (3) on the downbeat (Examples 3f–g). For iambic trimeter, a single upbeat eighth or quarter note was his customary default (Examples h–i). As Example 3 demonstrates, Mozart heavily favored neutral barring for both verse types. German barring was his regular second choice.

Zaide, “Ihr Mächtigen seht ungerührt,” mm. 11–13.

Die Entführung, “Ich baue ganz auf deine Stärke,” mm. 41–44.

Die Entführung, “Nie wird ich deine Huld verkennen,” mm. 64–66.

Zaide, “Ruhe sanft, mein holdes Leben,” mm. 79–82.

Die Entführung, “In Mohrenland gefangen war,” mm. 5–7.

Zaide, “Der stolze Löw’ läßt sich zwar zähmen,” mm. 33–35.

Die Entführung, “Wenn der Freude Thränen fliessen,” mm. 65–68.

Zaide, “Ich bin so bös’als gut,” mm. 33–35.

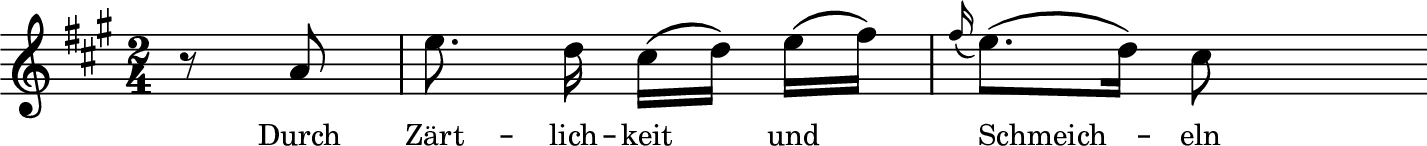

Die Entführung, “Durch Zärtlichkeit und Schmeichlen,” mm. 8–10.

Mozart’s common rhythmic profiles for single lines of iambic tetrameter (a–g) and iambic trimeter (h–i), taken from Zaide and Die Entführung aus dem Serail.

It is curious, then, that the opera’s lowest-born character adopts Italian barring to begin a number conspicuously more folk-like than any other in the Singspiel. Hermann Abert described Osmin’s comic strophic aria as “completely sui generis” and “loosely grafted onto the rest” of the otherwise serious opera ([1919–1921] 2007, 587). Indeed, German barring would have been more befitting of the character type, aria type, and indigenously German verse type, as shown in my alternate setting of mm. 21–27 in Example 4. The most familiar Mozartian example of such folksy German barring is that of Papageno’s “Der Vogelfänger bin ich ja” (assuming a compound 4/4 measure, as does Lippmann [1978]). (This example also includes the third phrase recast with Mozart’s customary neutrally barred profile for iambic trimeter, as presented in Examples 3h–i.) The first accented syllable of Osmin’s iambic lines beckons for such downbeat precedence. Even in Mozart’s Italian-barred setting, its perceived emphasis is so strong that a discriminating listener might, without benefit of the score, forgivably hear the opening three vocal phrases as they are barred in Example 4. The exercise of rebarring music, as I have done in Example 4, is a useful tool for hypothesizing what a listener might hear, wants to hear, or is unlikely to hear. I present Example 4 to demonstrate the plausibility of an alternate barring; there is surely no right or wrong way to hear these phrases. Proponents of Lerdahl and Jackendoff’s “strong beat early” preference rule (1983, 76) will be more inclined to hear the barring of Example 4. Proponents of end-accented phrases in the Riemannian tradition will gravitate toward Mozart’s original setting. (Riemann, of course, was a notorious and unabashed rebarrer; for a succinct overview of his metric theories, see Caplin 2011.) One is reminded of the similarly deceptive Italian barring of “Bei Männern, welche Liebe fühlen,” in which Mozart repeatedly emphasizes the first stressed syllable of iambic tetrameter on the second beat of the 6/8 measure, gradually inducing the listener, as Laskowski (1991) observes, to mistake those second beats for downbeats.

But whereas in “Bei Männern” Mozart delays the metric resolution until the duet’s conclusion, he does not leave the disoriented listener of “Wer hungrig” long adrift. To return to Example 2: a full measure of rest in m. 28 resets the metric order and enables Osmin to reenter on the downbeat of m. 29. Offering the line “Er ist fürwahr ein ganzer Narr,” he begins with a fragment (mm. 29–30) that rhythmically anticipates the complete presentation that follows in mm. 31–34. Labeled “B,” this phrase uses a neutrally barred rhythmic profile common for iambic tetrameter (cf. Example 3f–g), emphasizing the first weak syllable on the downbeat of m. 31: an over-correction of sorts that makes the barline’s position unequivocal. A repetition of this passage across mm. 35–40 reinforces that position. Osmin then concludes the verse with the final line, “Wer soll nicht drüber lachen? Ha!,” which he thrice casts in a pair of neutrally barred question-and-answer phrases across mm. 41–44, 45–48, and 49–54. The questions, which all take the same rhythmic profile and are labeled “C,” emphasize the first accented syllable with downbeat placement (cf. Examples 3a–b). The answers, which all take the same three-note upbeat profile and are labeled “D” and “D′,” diffuse the terminal exclamation across fits of laughter (cf. the upbeats to mm. 43, 47, and 51 with the three-note upbeat of Example 3e). Although Mozart treats Osmin’s “Ha!” differently with each verse, all but one of its elaborations are neutrally barred. The single exception is a sputtering passage at the close of the second verse (mm. 82–90), which cannot be categorized as a complete vocal phrase. Note, too, that the violins accompany these fits with a melodic contour similar to that of the first two vocal phrases (in which Osmin describes the foolish man’s sacrifices), conjuring a reminder of the reason for his laughter (compare the violins’ mm. 21–23 and 42–44).

The shift from Italian to neutral barring across Osmin’s verse has dramaturgic purpose. The first three lines of each stanza detail the men who, in Osmin’s estimation, unnaturally deny themselves easily accessible pleasures; in much the same way, Mozart’s Italian barring of those lines denies the iambic verse a more natural alignment with the downbeat—to the point that some listeners might misidentify the location of that primary pulse. Just as Osmin’s nincompoops needlessly eschew more comfortable situations, so too does the text-setting he uses while describing them. Conversely, Mozart selects neutrally barred rhythmic profiles idiomatic to iambic tetrameter for each stanza’s final two lines. Beginning on, or with an upbeat to, an unmistakable downbeat, Osmin aligns commensurate textual and musical stresses to matter-of-factly express what he believes is a matter of fact: these men are idiots and deserving of our ridicule.

"Alles fühlt der Liebe Freude"

Moving on a decade to the more familiar Die Zauberflöte, we find compelling dramatic and musical grounds for the inclusion of Monostatos’s “Alles fühlt der Liebe Freude” in the Entführung Osmin’s aria network. Every mention of Osmin in this paragraph refers to the Entführung character. Monostatos is the chief slave at Sarastro’s temple and, like Osmin, navigates a difficult relationship with a master whose hallmark benevolence does not extend so liberally to the servant class as it does to others. Both Osmin and Monostatos struggle to understand and to be understood by their (Western) interlocutors; Mozart fills their music with inflections of the alla turca patois to musically represent this unbridgeable divide. Moreover, both men loutishly and unsuccessfully pursue a woman of a race and culture different from their own. Monostatos’s wounds must sting more sharply than Osmin’s, though, as he regrets that Pamina and women like her reject him for the color of his skin and takes for granted a dismal future bereft of conjugal happiness. Regarding the racial stereotyping of Monostatos, see Cole (2005) and Scott (2007).

The primary concerns of my analysis are the aria’s irregular vocal phrase structure and deferment of normative hypermeter, since I believe these dramaturgically underscore both Monostatos’s freneticism and his outsider status. As in my previous study of the Entführung Osmin’s arias (Bastone Barrettara 2022–2023), I will identify metrically strong and weak measures based on a variety of parameters (harmonic progressions, melodic segments, repetitions, entry points, accents, etc.) guided by metrical preference rules (chiefly those defined by Lerdahl and Jackendoff [1983] and Temperley [2001]). I assume that duple-based phrase structures and hypermeters of regularly alternating strong/weak measures are normative. Arrows above the staff throughout the examples indicate measure strength (↓ = strong; ↑ = weak); brackets indicate hypermeasures where hypermeter is entrained. (Where hypermeter is not entrained, there are no brackets.)

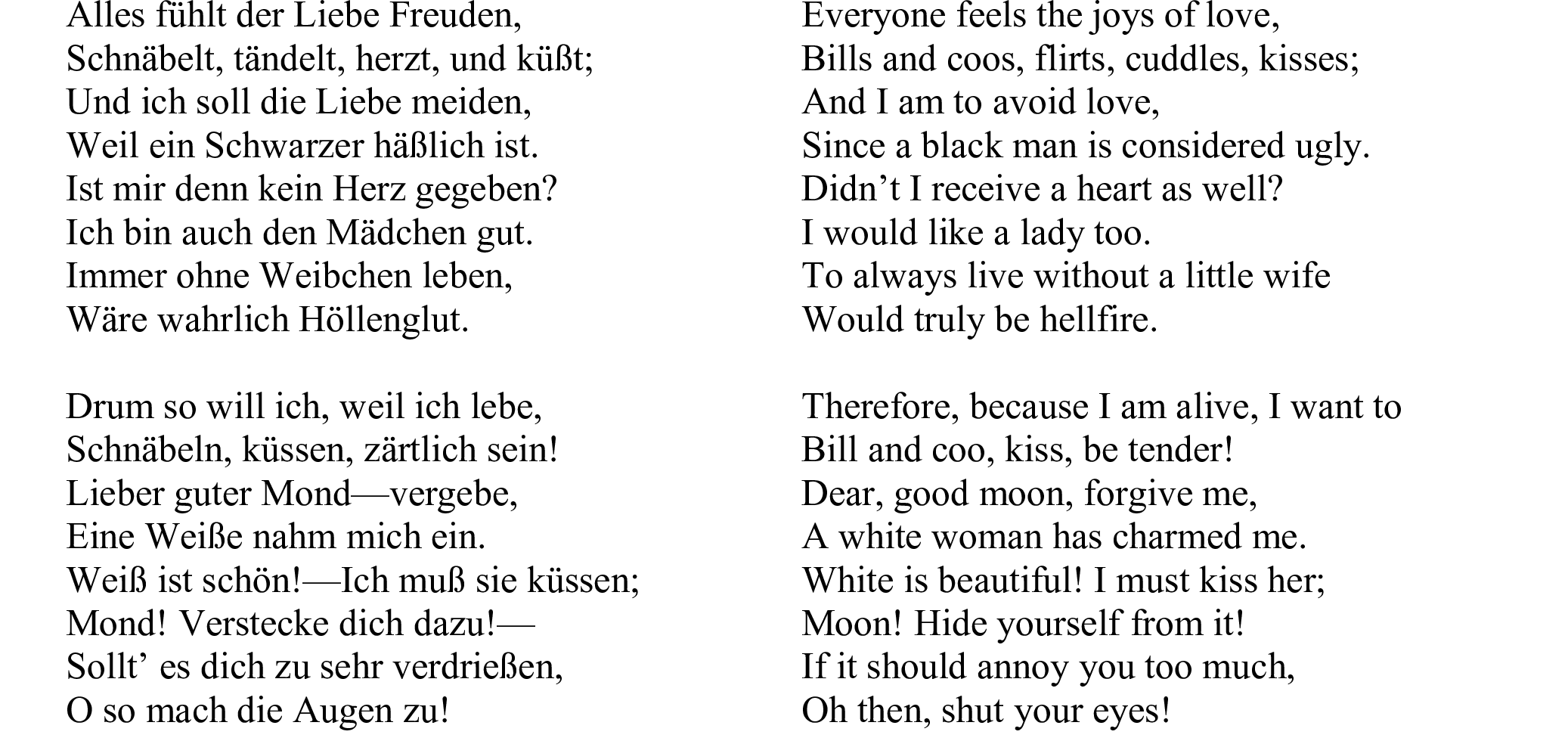

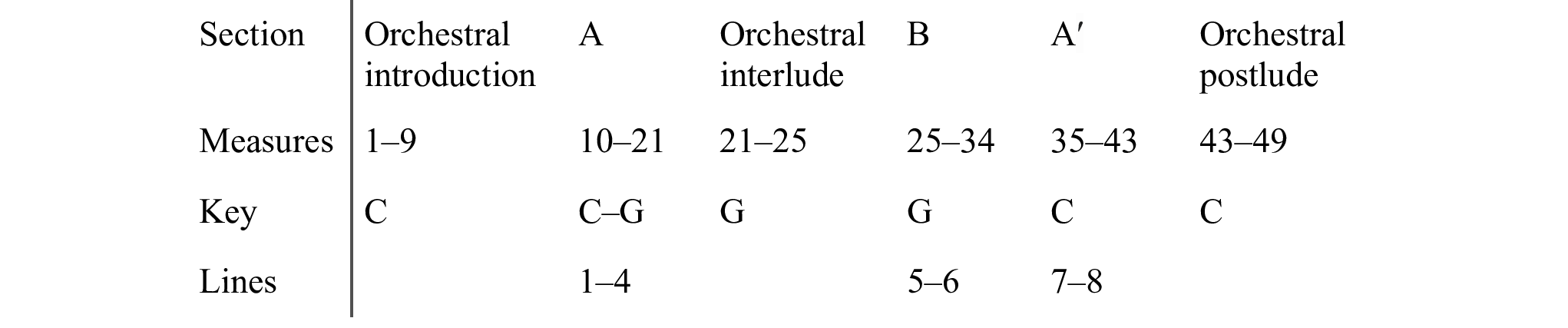

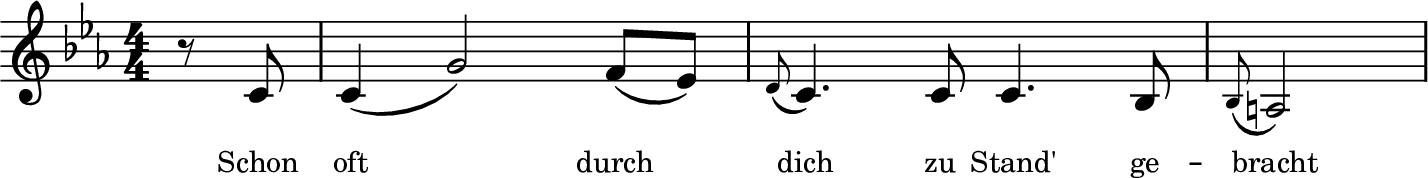

Monostatos delivers the strophic aria “Alles fühlt der Liebe Freuden” upon encountering Pamina alone and asleep in the garden at the beginning of Act 2. The two-stanza strophic setting is in C major, 2/4 time, and marked Allegro. The text is provided in Example 5a and a formal outline, which shows the ternary form of the strophic verses, is provided in Example 5b. In the first stanza, Monostatos bewails his loneliness and the prejudice that perpetuates it; in the second stanza, he plots to gain Pamina’s (physical) affection by force rather than by consent. We might note that the nine-measure orchestral introduction, comprising two phrases of five and four measures, previews the imbalanced phrase structures that will permeate the aria. It also incorporates a prominent piccolo and recurring raised fourth scale degree, both highly characteristic elements of the alla turca style.

As shown in Example 6, Monostatos enters in m. 10 and offers a series of five-, three-, and four-measure phrases on his way to the dominant, the junctures between which are marked by consecutive strong measures (mm. 14–15, 17–18). I hear m. 15 as strong because it assumes the precedent of the nearly identical m. 10. (If anything, the addition of the winds on the downbeat, not shown in the example, renders it even stronger.) I hear m. 18 as strong because it contains the first significant departure from the tonic since the vocal entrance and is emphasized by Monostatos’s agogic accent. The two vocal subphrases of mm. 18–21, then, together constitute Monostatos’s first normative four-measure phrase of regularly alternating strong and weak measures. Monostatos’s textual repetition in mm. 19–21 enables this normalization. It recalls Osmin’s use of the textual fragment “schnüren zu” as a hypermetrically normalizing element in the refrain of “O! wie will ich triumphieren” (Bastone Barrettara 2022–2023, 21–24). This regularity, however, is not a harbinger of structure: the orchestra interjects to reinterpret m. 21 as strong and concludes section A with a five-measure interlude, taking its metric cues from the opening vocal phrase on which it is based. I should note that in interpreting m. 18 as strong and as the start of a new vocal phrase, I privilege the harmony, linguistic stress, and length preference rules as defined by Temperley (2001, 357–8). Doing so also allows Tetzel’s parallelism rule (see Rothstein 2011, 96) to apply to mm. 18–19 and 20–21. One could, however, hear the phrase beginning in m. 15 as extending to the downbeat of m. 19, resulting in a five-measure unit that corresponds in length to the preceding vocal phrase (mm. 10–14). Such a hearing, which may especially strike the ear of a first-time listener, privileges the parallelism rule. Both interpretations are possible; neither projects a normative phrase structure. I favor the interpretation shown in Example 6, in part because it emphasizes the revelatory nature of the text: “weil ein Schwarzer häßlich ist.”

Section B (mm. 26–34) makes an eccentric attempt at phrase-structural and metrical patterning by way of three-measure vocal phrases that establish a triple hypermeter, the hypermeasures of which are delineated by brackets labeled “I,” “II,” and “III” in Example 6. These hypermeasures adopt the most common metric configuration of a three-measure unit: outer strong measures and a weak central measure. My interpretation of the latter two warrants explanation: I hear m. 29 as strong because of Monostatos’s initial agogic accent, the new dominant harmony, and the orchestra’s downbeat mfp; m. 30 as weak owing to Monostatos’s repeated D and the dominant prolongation by the orchestra, achieved by half notes tied over the barline; and m. 31 as strong because of the harmonic change. (The same reasoning applies to the repetition of this phrase in mm. 32–34). Although the hypermeter provides a pattern onto which Monostatos—and the listener—can belatedly latch, there arises an odd stop-and-go quality from the consecutive strong measures that bookend each hypermeasure. On the abnormality of triple hypermeters, see Rodgers (2011), De Souza and Lokan (2019), and Rothstein (1989).

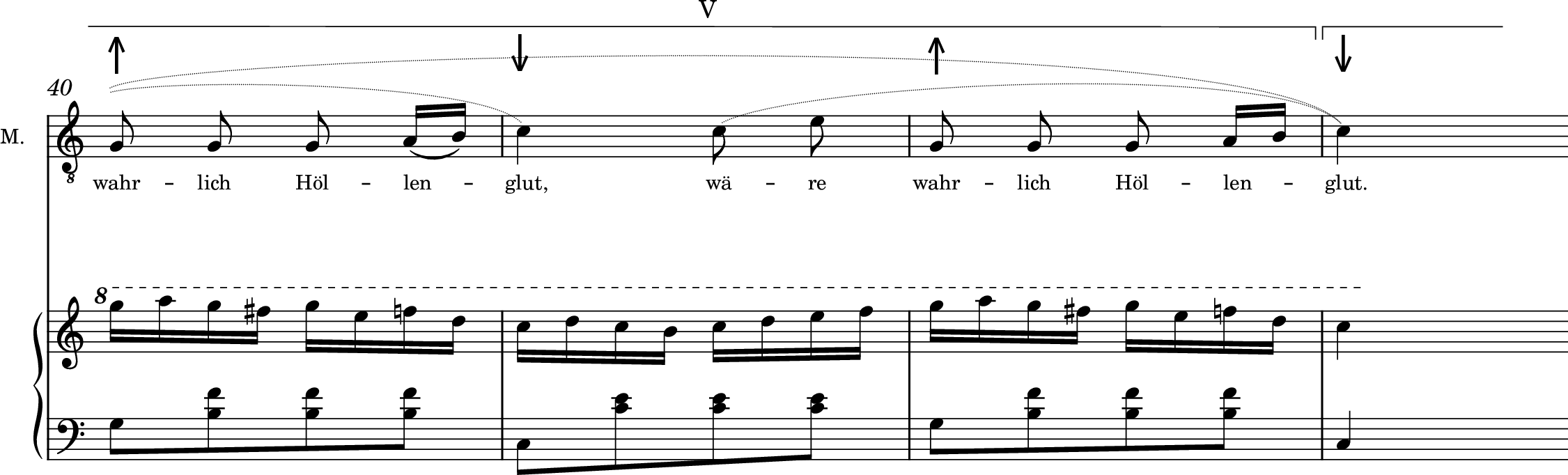

Section A′ reinstates the key of C major upon its arrival in m. 35; Example 6 identifies a regular alternation of strong and weak measures throughout, allowing a normative quadruple hypermeter to (finally) take root. Its hypermeasures are indicated by the brackets labeled “IV” and “V” above the staff. Closing areas like section A′ typically adopt (or maintain) metric stability to induce a sense of finality, and Monostatos’s phrases do their part by supporting the strong-weak alternation. Yet their end-accented structures resist total conformity: unbalanced at five and four measures apiece (mm. 35–39; 40–43), they both conclude in the first strong measure of a hypermeasure (mm. 39, 43), and the second begins in a weak second measure (m. 40). Monostatos does not (or perhaps cannot) align his vocal phrases with the metric groupings. Closing areas often contain end-accented phrases (see Temperley 2003), but I still think it reasonable, in the context of this metrically capricious aria, to hear Monostatos’s end accents as another quirk of his metric characterization. (The Entführung Osmin produces a similar effect, though not in a closing section, with his asynchronous phrases across mm. 87–111 of “O! wie will ich triumphieren” [Bastone Barrettara 2022–2023, 24–28].)

Between the phrase structural irregularity of section A, the triple hypermeter of section B, and the offset vocal phrases of section A′, Monostatos never quite settles into his own aria. This musical unease, exacerbated by the delayed hypermetric entrainment, dramaturgically reinforces two harsh realities for Monostatos: first, that his smoldering desperation—from which he seeks respite by iniquitous means in the second verse—has driven him to think and communicate frenetically; second, that just as he cannot physically conform to those who reject him, neither can he do so expressively. (The opera’s protagonists adopt balanced phrase structures by default.) Monostatos also strongly evokes the idiomatic phrase language that I identified in the Entführung Osmin’s arias, which similarly evades hypermetric entrainment, misaligns vocal phrase structures with hypermetric patterns, and projects consecutive measures of equal weight when Osmin is addled by strong emotion (Bastone Barrettara 2022–2023).

***

What can we deduce from a comparison of these two arias, and what can be said of their place in the wider aria network of the Entführung Osmin? To start, we might note that where the Zaide Osmin’s aria adopts irregular barring and metric stability, Monostatos’s adopts regular barring and metric instability. “Wer hungrig” establishes a quadruple hypermeter from the start, as shown by brackets above the staff in Example 2. The shift from Italian to neutral barring does not affect this pattern, owing at least in part to the silent m. 28, which is the fourth weak measure of a hypermeasure. “Alles fühlt,” on the other hand, contains only neutrally barred vocal phrases—a simple style to express a simple desire—but does not establish a normal hypermeter until its end. Dramaturgy can account for these contrary features. Mozart underpins Osmin’s surety of self and speech with a level metric foundation atop which the meaningful nuances of his barring are made more readily perceptible. He casts Monostatos’s plainer message in phrases that, though uniformly barred, are largely incompatible with normative hypermetric entrainment for the reasons I noted earlier (e.g., his befuddlement and nonconformity). Where metric stability expresses Osmin’s confidence, metric instability expresses Monostatos’s lack thereof.

Widening our lens, we cannot yet claim any broad compositional trends for the Entführung Osmin’s aria network, having explored but a small cross section of its potentially vast lattice. But an interesting consistency does begin to emerge. In the arias I have considered, Mozart dramaturgically calls upon irregular phrase structures or text-setting whenever either one of the Osmins, Monostatos, or those they reference exercise poor judgement: the Entführung Osmin threatens unprovoked violence in unhinged outbursts; Monostatos indignantly prepares to force himself on Pamina; the men at whom the Zaide Osmin laughs sacrifice satisfaction in a manner wholly illogical. Of course, these three characters are Eastern caricatures, their stereotypical vices exploited for easy laughs and Western moralization. A modern sensibility does not blame Monostatos for resenting the prejudice that precludes his contentment.

It is significant, though, that at the beginning and end of his operatic maturity, Mozart manipulated certain time-based musical parameters to portray irrationality in the characterizations of his non-Western male servants. By preventing or disrupting what tend, in late-eighteenth-century music, to be more reliably stable elements (e.g., an easily identifiable downbeat or recurring duple-based phrase structures), Mozart conveys that something—both psychologically and musically—is fundamentally amiss.

Works Cited

Abert, Hermann. [1919–1921] 2007. W.A. Mozart. Translated by Stewart Spencer. Edited by Cliff Eisen. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Bastone, Danielle. 2017. “The Analysis of Musical Dramaturgy in Mozart’s Die Entführung aus dem Serail.” PhD diss., The Graduate Center of the City University of New York.

Bastone Barrettara, Danielle. 2022–2023. “Mozart’s Osmin and the Phrasing of Discomposure.” Theory and Practice 47–48: 1–34.

Bent, Ian. 1994. Music Analysis in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Berke, Dietrich. 2003. “Vorwort.” In Zaide (Das Serail), KV 344 (336b), composed by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Vocal score based on the NMA Urtext (edited by Heinz Moehn). Kassel: Bärenreiter.

Caplin, William. 2011. “Criteria for Analysis: Perspectives on Riemann’s Mature Theory of Meter.” In The Oxford Handbook of Neo-Riemannian Music Theories, edited by Edward Gollin and Alexander Rehding, 419–39. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cole, Malcolm S. 2005. “Monostatos and his ‘Sister’: Racial Stereotype in Die Zauberflöte and its Sequel.” The Opera Quarterly 21: 2–26.

De Souza, Jonathan and David Lokan. 2019. “Hypermetrical Irregularity in Sonata Form: A Corpus Study.” Empirical Musicology Review 14 (3–4): 138–43.

Grave, Floyd K. 1985. “Metrical Displacement and the Compound Measure in Eighteenth-Century Theory and Practice.” Theoria 1: 25–60.

Laskowski, Larry. 1991. “Voice Leading and Meter: An Unusual Mozart Autograph.” In Trends in Schenkerian Research, edited by Allen Cadwallader, 41–49. New York: G. Schirmer.

Lerdahl, Fred and Ray Jackendoff. 1983. A Generative Theory of Tonal Music. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Lippmann, Friedrich. 1978. “Mozart und der Vers.” In Analecta Musicologica, Vol. 18: Colloquium Mozart und Italien (1974: Rom), edited by Friedrich Lippmann, 107–37. Cologne: A. Volk.

Riemann, Hugo. [1903] 2000. System der musikalischen Rhythmik und Metrik. Translated by Bradley C. Hunnicutt in “Hugo Reimann’s System der Musikalischen Rhythmik und Metrik, Part Two: A Translation Preceded by Commentary.” PhD diss., University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Riemann, Hugo. 1912. Vademecum der Phrasierung. Dritte Auflage. Leipzig: Max Hesses Verlag.

Rodgers, Stephen. 2011. “Thinking (and Singing) in Threes: Triple Hypermeter and the Songs of Fanny Hensel.” Music Theory Online 17 (1).

Rothstein, William. 1989. Phrase Rhythm in Tonal Music. New York: Schirmer Books.

Rothstein, William. 2008. “National Metrical Types in Music of the Eighteenth and Early-Nineteenth Centuries.” In Communication in Eighteenth-Century Music, edited by Danuta Mirka and Kofi Agawu, 112–59. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rothstein, William. 2011. “Metrical Theory and Verdi’s Midcentury Operas.” Dutch Journal of Music Theory 16: 93–111.

Schaubhut Smith, Judyth, et al., translators. 1991. The Metropolitan Opera Book of Mozart Operas. New York: Harper Collins.

Schmid, Manfred Hermann. 2003. “Deutscher Vers, Taktstrich und Strophenschluss Notationstechnik und ihre Konsequenzen in Mozarts Zauberflöte.” Mozart Studien 12: 115–45.

Scott, Derek B. 2007. “A Problem of Race in Directing Die Zauberflöte.” In “Regietheater”: Konzeption und Praxis am Beispiel der Bühnenwerke Mozarts. Series: Wort und Musik: Salzburger akademische Beiträge, No. 65. Austria: Müller-Speiser, Anif-Salzburg: 338–44.

Temperley, David. 2001. The Cognition of Basic Musical Structures. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Temperley, David. 2003. “End-Accented Phrases: An Analytical Exploration.” Journal of Music Theory 47 (1): 125–54.

Tyler, Linda. 1991. “‘Zaide’ in the Development of Mozart’s Operatic Language.” Music & Letters 72 (2): 214–35.

Webster, James. 1991. “The Analysis of Mozart’s Arias.” In Mozart Studies, edited by Cliff Eisen, 101–99. New York: Oxford University Press.

Williams, Clive. 2014. English translation of Zaide libretto included in pamphlet of Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus. Zaide. Concentus Musicus Wien, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, with Tobias Moretti, Diana Damrau, and Michael Schade. Recorded 2006. Deutsche Harmonia Mundi. Compact disc.