الحركة بركة [Movement is a blessing]

When the National Arab Orchestra (NAO) took the stage in November 2019 at the Ithra Theater in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, the energy was equally palpable on stage and off. The seated audience, wearing pressed suits and lavish gowns, were active participants throughout the night’s event. A YouTube video, even through its small and restricted frame, leaves us a digital trace of their affective engagement. For those reading this article in print, the performance here, as well as all other video and audio examples referenced throughout the article, can be found on my website: https://www.issaaji.com. This particular performance serves as the basis for my analysis of the song’s rhythmic-temporal disruptions, specifically the one occurring at 0:25.

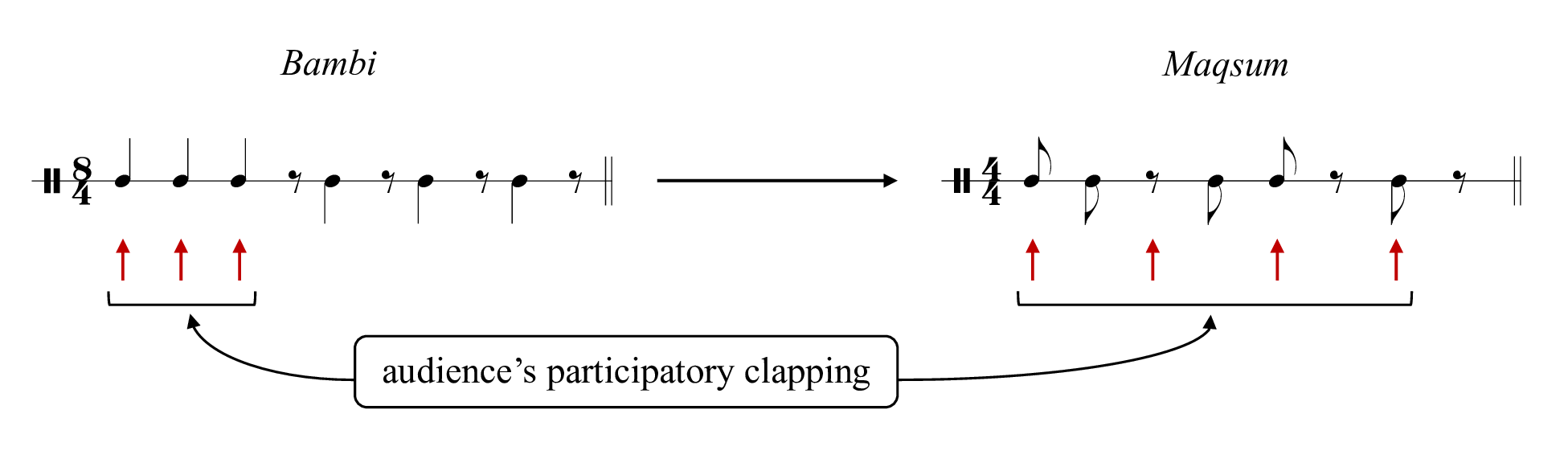

This concert featured canonical selections from two of Arab music’s most revered female vocalists (muṭribāt) of the twentieth century: Asmahān (1912–1944) and Umm Kulthūm (ca. 1904–1975). At the start of one of Umm Kulthūm’s most popular songs, “Alf Leila wi Leila” (1969, “A Thousand and One Nights”), Michael Ibrahim, the orchestra’s founder and conductor, calls the audience into participatory action. With his back turned toward his own orchestra, Ibrahim faces the audience (0:08, 0:13, and 0:17) to invite listeners to mimic three large clapping gestures, each one landing on the first three quarter notes of the song’s opening rhythmic mode (īqāʿ) called the Bambi. After cycling through the rhythm six times for around 25 seconds, the music abruptly switches to another īqāʿ called the Maqsum; listeners reorient to the new rhythm by clapping on every quarter-note beat of its 4/4 cycle. Example 1 illustrates the move between the two īqāʿāt (plural of īqāʿ) in basic notation. This rhythmic shift and others like it, which I call “rhythmic-temporal disruptions,” alter the trajectory of the music’s temporal structure, prompting listeners to engage and entrain (through participatory clapping) to the new rhythmic mode. Following Hasty (1997), I describe listeners’ embodied experience of meter and rhythm as a form of engaging with music’s temporal unfolding. For more on the body’s engagement with musical time, see also Kozak (2020). More than just a ubiquitous practice in Arab performance settings, they facilitate a direct engagement with musical time in a way that orients listeners’ minds and bodies toward a state of musical ecstasy known as ṭarab, illuminating affect and the emergence of temporality as two prominent aspects of Arab musicking.

This article develops an analytical model that addresses the association between perceived transformations of musical time and the Arab concept of ṭarab. By describing the interrelation of rhythm, temporality, and feeling in ṭarab performance, I argue that rhythmic-temporal disruptions function as a sonic resource (Shelley 2019, 185) for experiencing ṭarab. I also show that as rhythmic-temporal disruptions fracture the linear flow of musical time, they leave openings in the musical surface that invite listeners to affectively engage with the music’s temporal structure. Integrating Toussaint’s (2013) method of mapping cyclical rhythms with De Souza’s (2017) notion of consistency and displacement, my analytical model elucidates the degree of rhythmic-temporal distance traversed in the movement from one īqāʿ to the next. I then use this model to provide a close reading of the rhythmic-temporal disruption described above. De Souza’s (2017, 89) use of the terms “consistency” and “displacement” originates with Straus (2003). As it applies to voice leading, consistency measures general uniformity, counting the number of voices moving by the same interval (Straus 2003, 315). Displacement, by contrast, measures the total number of semitones traversed (ibid., 320). My application of the terms is described below. Revealing the proximity between changing rhythmic modes in this way not only quantifies the disruptive force created by rhythmic-temporal disruptions, but also sheds light on how these sonic disturbances correlate with the feeling of ṭarab.

I begin with a brief primer on ṭarab, establishing the connection between altered senses of musical time and affective experience. I then move to an analysis of the opening of the NAO’s rendition of “Alf Leila wi Leila,” introducing my analytical model to shed light on rhythmic-temporal disruptions and how their perceived transformations of musical time afford salient opportunities for experiencing ṭarab. Finally, I grapple with issues of physicality and phenomenology to discuss listeners’ relationship to rhythmic-temporal disruptions in experiential terms.

The feeling of musical ecstasy, participation, and "time splitting away from time"

Ṭarab, a term that resists direct English translation, generally denotes two interrelated concepts. First, the term refers to a state of heightened emotionality that is often described in English as a form of musical “ecstasy,” “rapture,” or “enchantment” (Shannon 2006, 161). Like other forms of musical affect such as Turkish keyif or Spanish duende, experiential descriptions of ṭarab tend to elude the specificity that the term “emotion” typically implies. Scholars adhering to this view tend to follow a version of the intellectual tradition put forth by affect theory, where emotions are seen as rigid linguistic fixings of affect’s immediate, corporeal, and asignifying “intensities,” which cannot be adequately captured with the tools of language. According to Brian Massumi (2002, 61), who is arguably the most influential affect theorist today, emotions are “a contamination of empirical space by affect, which belongs to the body without an image.” For insightful critiques of affect theory and its sharp bifurcation of emotion and affect, see Leys (2011), Brinkema (2014), Garcia (2020), and Grant (2020). “It would be misleading,” writes ethnomusicologist and preeminent scholar of Arab music Ali Jihad Racy, “to explain the ecstatic state itself in plain sentiment-related terms” (2003, 203). For this reason, Racy (1991; 2003) centers his discussion of ṭarab around the Arabic word iḥsās (meaning “feeling”) to avoid commitment to any one emotional or sentimental profile. Second, ṭarab is also used in reference to the essentially secular style of mid-to-late-twentieth-century “art music” of Near-Eastern Arab cities (including Cairo, Damascus, and Aleppo), where the experiencing of the ecstatic state serves as primary criterion for a successful performance. The music of Egyptian Umm Kulthūm continues to occupy a central position within “ṭarab culture,” a term used by some scholars (Danielson 1997; Racy 2003) to refer to the shared set of cultural practices, affects, and discourses that accompany ṭarab as a musical and aesthetic style.

In the context of performance, the efficacy of ṭarab—understood as both a mode of affective engagement and a musical style—hinges on human interaction, where the shared exchange of various bodily gestures and vocal exclamations is interpreted as a sign of approval and reassurance of an effective performance. As Racy notes, ṭarab “derives its momentum, emotional efficacy, and aesthetic consistency from human interplay, through a feedback process involving active and direct communication between the artist and the initiated listener” (1991, 11). As such, performers and listeners alike enact aspects of “human interplay” by responding to the performance with certain idiomatic gestures, both kinesthetic and vocal, which in turn lead to “feedback processes” that heighten the affectivity of the musical discourse. For a systematic account of this process within the context of ṭarab, see Racy’s discussion of the “ecstatic feedback model” (1991). Highlighting the importance of this expressive interplay, anthropologist Jonathan H. Shannon goes so far as to suggest that “the shouts and gestures that occur within the context of a performance may come to stand for the performance itself” (2006, 171). Like many other musical traditions, where expressive exchanges between performers and listeners are central to the process of music-making—from jazz (Berliner 1994; Monson 1996) to electronic dance music (Butler 2006; Garcia 2020)—ṭarab performances thrive on the immediacy of human interaction. My understanding of the participatory dynamics of ṭarab performance is informed by Thomas Turino’s (2008, 28) conception of participation, the “sense of actively contributing to the sound and motion of a musical event through dancing, singing, clapping, and playing musical instruments when each of these activities is considered integral to the performance.” Emphasizing this point in a 1990 interview, celebrated ṭarab vocalist Ṣabāḥ Fakhrī (1933–2021) states:

Of course I sense people’s reactions from their movements and by observing their inner emotional tribulations and their responses (tajāwub) to what I am singing. […] It is the audience that plays the most significant role in bringing the performance to a higher plateau of creativity (ibdāʿ). I like the light in the performance hall to remain on so that I can see the listeners and interact with them. If they respond I become inspired to give more. As such we become reflections of one another. I consider the audience to be me and myself to be the audience (quoted in Racy 1991, 8).

Fakhrī’s description of performers and listeners becoming “reflections of one another” is a particularly telling characterization of the experiential and participatory dynamics of ṭarab performance. His preference for keeping the lights on so that he can sense people’s “movements” and observe their “inner emotional tribulations” works to dissolve the boundary between Fakhrī and his audience, providing an emic illustration of what Alfred Schutz (1977) described as a “mutual tuning-in relationship,” or what Émile Durkheim (1915) called “collective effervescence.” To this end, moments of communal entrainment, as exemplified in the participatory clapping described in the opening vignette, allow listeners to engage and entrain not only to each other, but to the music’s rhythmic structure in shared movement. As I described at the outset, the shift from one īqāʿ to the next (from Bambi to Maqsum) was met with a stylistically appropriate shift in the placement of the audience’s participatory clapping (see Example 1), altering the music’s temporal structure and the audience’s experience of it. Alluding to the expressivity of such moments, one of the experiential descriptors of ṭarab shared among performers and listeners is that of an altered sense of time (Racy 2003, 125). This bears witness to the claim that “ṭarab, like similar states of heightened emotionality experienced in the course of performance, arises as a result of perceptions of transformations in time” (Shannon 2006, 177). Similar sentiments are echoed by Racy, though in metaphorical terms, where he describes the feeling (iḥsās) of ṭarab as “time splitting away from time,” which “appears to imply the existence of two alternate modes of temporal awareness, one pertaining to ecstatic time and the other to non-ecstatic time, or time proper” (2003, 125; emphasis added). I suggest that these temporal transformations manifest musically as rhythmic-temporal disruptions. Occurring at various degrees—from a complete loss of musical time to more subtle shifts in temporal awareness—they act as sonic mechanisms for the experiencing of ṭarab. That is to say, audiences experience these rhythmic disruptions, and it is the disruption itself—the altered sense of time—that facilitates in part the sense of musical ecstasy associated with ṭarab. The analytical model presented next will shed light on these claims.

Analyzing īqāʿāt and rhythmic-temporal disruptions in ṭarab performance

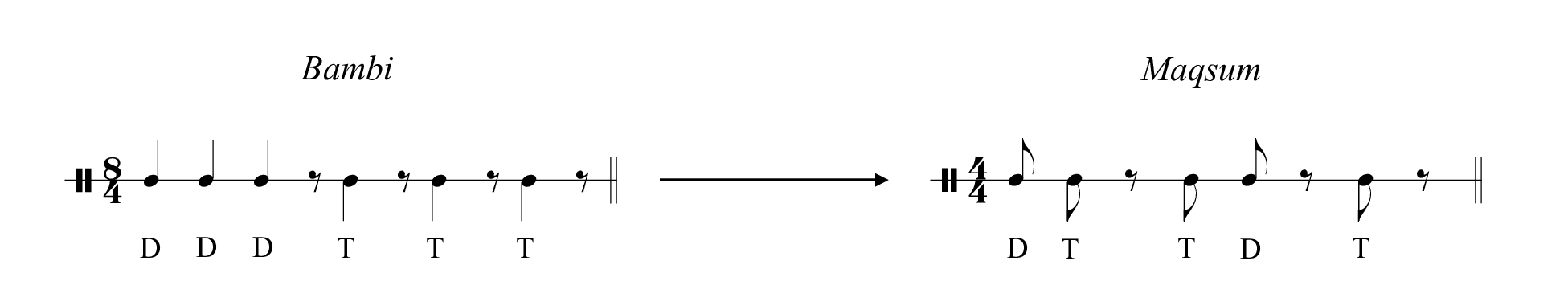

Arab īqāʿāt, which are typically played on membranophonic percussion instruments, are characterized by two distinct types of percussive attacks that constitute what I refer to as the “timbre/pitch” content of a given īqāʿ. This is indicated by the Ds and Ts shown underneath each rhythm in Example 2, where “D” stands for what is called a dumm beat—a deep, emphatic sound played with the palm (shown with stems pointing upward)—and “T” stands for what is called a takk beat—a light, crisp sound played with the fingers (shown with stems pointing downward). Each īqāʿ may thus be understood along two separate parameters: 1) its basic underlying rhythmic structure, and 2) its timbre/pitch content. This framework generally applies to all percussion instruments comprising a given percussion section within a particular performance setting. In the case of the NAO’s performance of “Alf Leila wi Leila,” the percussion section consists of two ṭablah-s (a vase-shaped single-headed drum), a riqq (a small, handheld tambourine), a set of bongos, and a katim (a large frame drum). For an image of these instruments, refer to 0:13 in the video above. During live performance, it is rare for īqāʿāt to be performed as simply as portrayed in Example 2; in practice, they are typically embellished with a wide variety of improvisatory grace notes and muted percussive hits. To hear each īqāʿ shown in Example 2 in isolation, refer to the website cited in note 1. Notwithstanding these improvisational nuances, īqāʿāt are still understood and identified as “self-contained structures,” each representing a unique and recognizable musical unit (Racy 2003, 113).

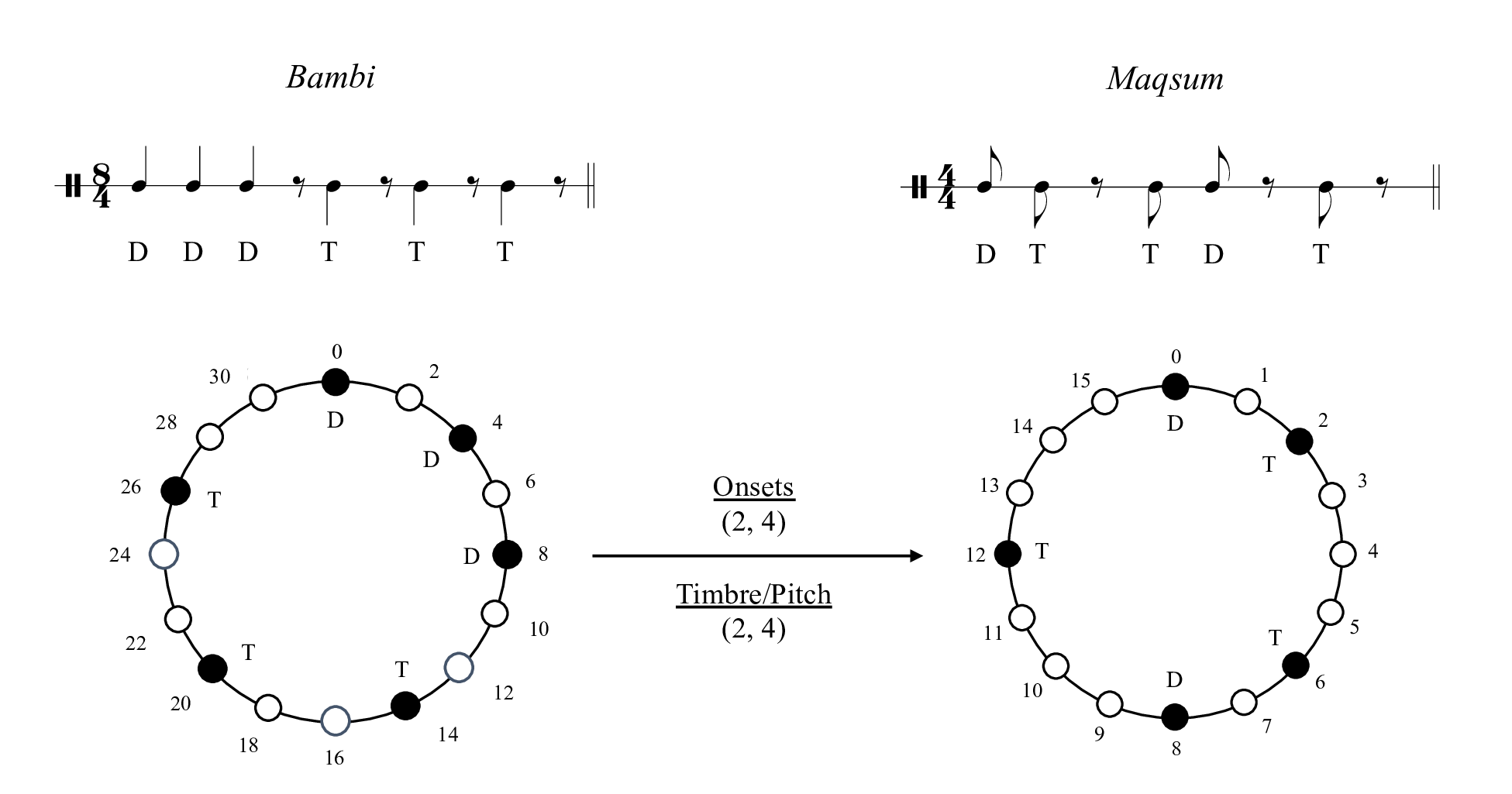

With this preliminary understanding of īqāʿāt in place, how might we now account for the movement between them, the crux of rhythmic-temporal disruptions? Following Toussaint’s method of mapping cyclical rhythms, Example 3 shows the mapping of the Bambi and Maqsum onto their respective rhythmic timelines. Both timelines divide each īqāʿ at the sixteenth-note level. Note here that the Bambi, notated in 8/4, following notation provided by Johnny Farraj and Sami Abu Shumays (2019, 114), doubles the length of the Maqsum, keeping its characteristic three-dumm-beat pattern on the first three quarter notes of each bar. To reflect the 8/4 meter in the Bambi-s rhythmic cycle, the numbers beside each of its nodes are doubled in order to keep both cycles numerically proportionate to one another, allowing for an accurate comparison between the two īqāʿāt. When the transliteration of Arabic nouns in their plural or possessive forms prove unnecessary or awkward, I use the English ending “-s” to end the word (e.g., Bambi-s and ṭablah-s). Whereas the Bambi contains six onsets, the Maqsum contains five. When accounting for the move from the Bambi to the Maqsum, two onsets remain “consistent” [0 and 8], while four have been “displaced” [4, 14, 20, and 26]. I represent this relationship of similarity and difference numerically as an ordered pair (x, y), following De Souza’s notion of consistency and displacement, where x equals the number of elements that stay consistent between the two rhythms (i.e., two onsets at pulse numbers 0 and 8) and y equals the number of elements that have been displaced (i.e., four onsets at pulse numbers 4, 14, 20, and 26). As shown in Example 3, this yields the ordered pair (2, 4) as it pertains to the placement of onsets. I apply the same logic to the timbre/pitch content. Because each of the two consistent pulse numbers (i.e., 0 and 8) retain their timbre/pitch content—that is, two dumm beats—the ordered pair pertaining to timbre/pitch yields the same result, (2, 4). Nuancing our understanding of the rhythmic-temporal disruption under discussion, what these two ordered pairs reveal is the degree of proximity between the two īqāʿāt along two separate parameters—placement of onsets and timbre/pitch content.

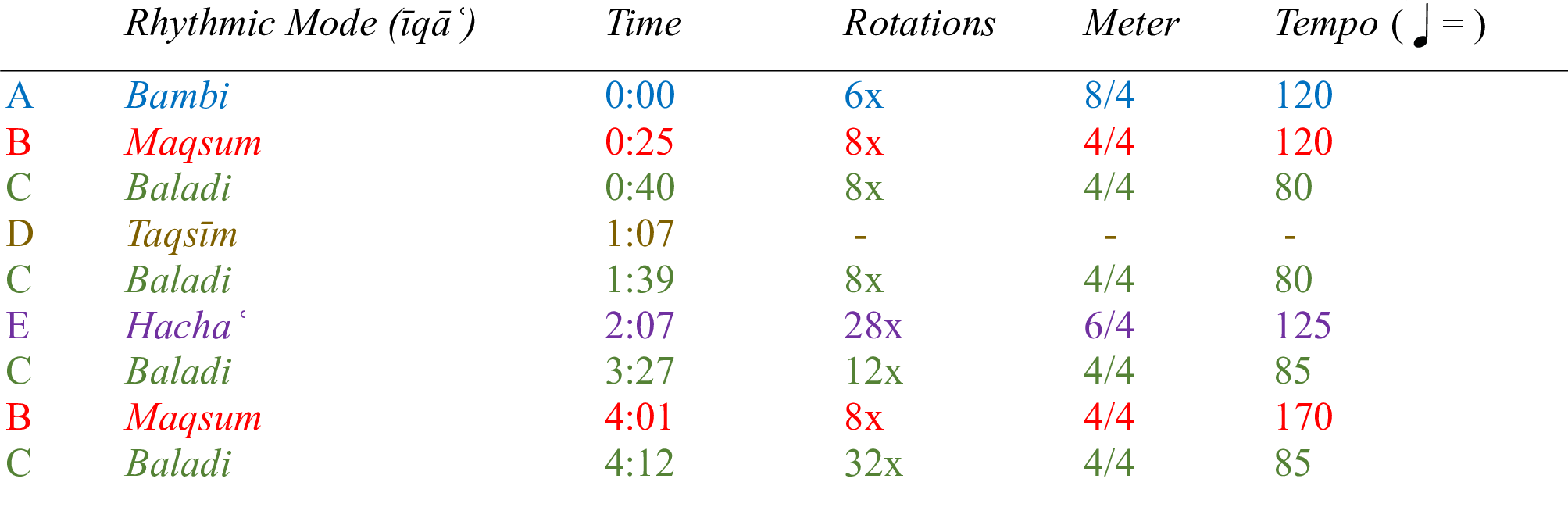

To better understand the relevance of these ordered pairs, let us consider two other instances of rhythmic-temporal disruption in the NAO’s rendition of “Alf Leila wi Leila.” Example 4 shows the formal progression of īqāʿāt throughout the song’s orchestral introduction (muqaddima), which includes (moving from left to right) the formal letter, name, timestamp, number of rotations, meter, and tempo of each īqāʿ. Note that while the opening move from Bambi to Maqsum (i.e., the move from A to B in Example 4) does not involve a change in tempo—both īqāʿāt occur at roughly 120 beats per minute—the second rhythmic shift moving from the Maqsum to the Baladi (i.e., the move from B to C in Example 4) involves not only a change in īqāʿ, but also a notable change in tempo from 120 to 80 beats per minute. If, for the time being, we artificially ignore this tempo change and assume a consistent tempo between the two rhythms, two ordered pairs (5, 0) and (4, 1) would result from their shift, as shown in Example 5a. Even without mapping the two rhythms, we can observe their close proximity and low degree of rhythmic-temporal displacement; the two īqāʿāt share identical rhythmic structures, differing only in timbre/pitch content on the second eighth note—where the Maqsum plays a takk beat, the Baladi plays a dumm. But this is an incomplete portrayal of what happens in the song. Example 5b, which accounts for the tempo change, considers the Maqsum-s moving at a rate 1.5 times faster than the Baladi, a ratio of 3:2. Multiplying each onset of the Maqsum (as represented in Example 5a) by 1.5 yields an entirely different, more accurate set of ordered pairs: (3, 2) and (1, 4). In this case, and in rhythmic-temporal disruptions more generally, tempo changes typically reveal higher degrees of displacement, enhancing the notion of “time splitting away from time” through pronounced changes to the music’s temporal structure. For a related discussion on tempo changes (specifically, tempo escalation) in Sufi music of North India and Pakistan, see Qureshi (1986, 204–5).

The issue of altering one’s temporal perceptions is made most apparent in rhythmic-temporal disruptions involving shifts to a taqsīm (labeled as D in Example 4). Derived from the verb qassama-yuqassimu, meaning “to divide,” a taqsīm is not a rhythmic mode, but a (typically) unmetered moment of instrumental improvisation. As shown in Example 4, the taqsīm occurring at 1:07 is preceded by the Baladi (the move from C to D). Rhythmic-temporal disruptions involving shifts to taqāsīm (plural of taqsīm) represent complete departures away from the normal flow of musical time, where the move from metered to unmetered time marks a clear-cut division in the music’s temporal organization. In describing the experiential characteristics of taqāsīm, Shannon notes that they feature a “detemporalizing” effect that brings listeners to a margin “between the temporalities of everyday life and those of transcendent experience” (2003, 87). Here, the taqsīm serves as his primary exemplar for illustrating the claim that states of ṭarab rely on perceived temporal transformations. Yet, what my analytical perspective makes clear is that Shannon’s claim need not be bound to rhythmic-temporal disruptions involving only the taqsīm. By extending it to include changes between various (metered) īqāʿāt, my contribution accounts for more subtle manifestations of temporal transformation.

But how can we use the insights gleaned from my analytical model to rethink rhythmic-temporal disruptions in experiential terms? To begin, we might first consider the physicality involved. By altering the music’s temporal structure in the ways described thus far, listeners are invited to respond to the rhythmic event with their bodies in affective ways. Maria A. G. Witek’s (2017) discussion of syncopation and embodiment in groove-based musics provides a useful starting point. For Witek, syncopation “opens up empty spaces in the rhythmic surface” to which the body then responds by “filling in” the gaps through processes of entrainment (2017, 138). “By filling in temporal gaps,” Witek explains, “bodies extend into the musical structure, and the desire to fill the gaps and complete the groove affords a participatory pleasure” (ibid.). While certainly not the kinds of “syncopation” that Witek had in mind, I suggest that rhythmic-temporal disruptions function similarly: their ability to fracture the music’s rhythmic surface provides a disruptive force that opens up space for listeners to extend themselves into the musical structure in participatory ways. When viewed in this light, higher degrees of rhythmic displacement create more space for the participatory pleasures of kinesthetic action.

Therefore, the two ordered pairs resulting from my analytical model reflect not only the degree of proximity between changing īqāʿāt but also the degree of physicality involved when experiencing rhythmic-temporal disruptions. To visualize this potential physicality, let us return to where we began. In Example 3, I showed that the opening rhythmic-temporal disruption of “Alf Leila wi Leila” produced the two ordered pairs (2, 4) and (2, 4). Building on this example, Example 6 connects the dumm and takk beats of each cycle. Note here that the dumm and takk beats of the Bambi are siloed to the northeast and southwest corners of its cycle respectively. By contrast, the Maqsum-s more evenly dispersed layout of dumm and takk beats lends to its symmetrical construction. Reading the Maqsum as more symmetrical than the Bambi relies, of course, on where one draws their axis of symmetry. My interpretation is based on the meaning of the Arabic word maqsum (meaning “divided” or “distributed”), which refers to the rhythm’s simple division into two halves (see the vertical line connecting the two dumm beats at pulse numbers 0 and 8 in Example 6). For more on the Maqsum-s symmetrical division, see Farraj and Abu Shumays (2019, 107–8). Revealing a notable difference in geometrical layout, I read this rhythmic-temporal disruption as akin to what Racy calls the shift from “ecstatic time” to “time proper.” I correlate the Bambi-s rhythmic asymmetry (or irregularity) with ecstatic time, whereas time proper correlates with the symmetry (or regularity) of the Maqsum. Noting also the open circles that surround certain nodes in Example 6, which represent the audience’s participatory clapping, further illustrates the experiential dynamics of this rhythmic-temporal disruption; the move from the asymmetrical Bambi to the symmetrical Maqsum calls for a certain physicality that loosens listeners’ relationship with musical time. This observation suggests what Braxton D. Shelley calls a “paradoxical phenomenology.” As it pertains to gospel performance, Shelley explains that “intensified physicality actually loosens the believer’s relation to the material world, enhancing his or her connection to what is often called the ‘spiritual realm’” (2019, 186). The experiential dynamics of rhythmic-temporal disruptions create a similar paradox: the intensified physicality needed in rhythmic-temporal disruptions loosens listeners’ relation to musical time in a way that enhances their connection to the ecstatic state that ṭarab performances seek to achieve. Moreover, the communal participation that often results from such processes allows for bodies to be drawn together in the same place, at the same time, where shared conceptions of temporality tend to blur the boundary between self and other. This phenomenon can help explain why ṭarab is sometimes described as a “unity of feeling” (wahdat al-shu’ur), or the “affective melting” (dhawb) of many into one (Frishkopf 2001, 234).

Conclusions

Imagine yourself there, seated alongside the rest of the audience, watching the NAO’s performance of “Alf Leila wi Leila.” It is only a few seconds into the song that the orchestra’s conductor invites you and the rest of the audience to clap in unison on the first three quarter notes of the Bambi. Clap, clap, clap. Now imagine feeling the gradual accumulation of intensity that builds on each repetition of the rhythmic cycle. Then, shortly after, a change—an abrupt shift to Maqsum. The disruptive force enacted by this rhythmic shift fractures the musical surface, leaving behind a liminal space that heightens your awareness of the music, yet loosens your relationship to the flow of musical time. Following the audience’s lead, you adjust to the Maqsum by clapping on each of its four quarter-note pulses. At this point, you have become an active participant in the performance. Your mind and body extend into the musical structure and those around you. The feeling of being lifted out of everyday temporality moves you away from the material world and into the invisible domain of ecstatic experience. This is the function of rhythmic-temporal disruptions in ṭarab performance.

This article has provided further musical evidence for the established association between altered senses of time and the Arab concept of ṭarab. We have seen how rhythmic-temporal disruptions function as a sonic resource for experiencing the ecstatic state by materializing altered senses of time in sound. Examples of rhythmic-temporal disruptions are widespread throughout the ṭarab repertoire. Some notable examples include the NAO’s rendition of Umm Kulthūm’s “Ghanni li Shwayya Shwayya” (2:52), ʿAbd al-Ḥalīm Ḥāfiẓ’s “Zayy il-Hawa” (1:49), Ṣabāḥ Fakhrī’s “Yā Māl al-Shām” (3:20), and Sayyid Darwīsh’s “Yā Bahjat al-Rūh” (0:30). These performances can be found on the website cited in note 1. Timestamps apply only to those specific recordings, which are also referenced in the “Works Cited” list. Applying my analytical model to the opening rhythmic-temporal disruption of the NAO’s rendition of Umm Kulthūm’s “Alf Leila wi Leila,” I have also illustrated how listeners incarnate rhythmic-temporal disruptions with an intensified physicality, creating shared conceptions of time and place. Blurring the boundary between self and other, rhythmic-temporal disruptions also grant participants a palpable sense of kinesthetic empathy, as evidenced by Fakhrī when he states, “I consider the audience to be me and myself to be the audience.” While my analytical model may serve useful for music scholars wishing to track rhythmic-temporal proximities across cyclical rhythms, I should emphasize that relegating understandings of ṭarab to sonic properties alone is only part of a much larger, more complex affective process. Because ṭarab centers, in part, on forms of bodily empathy (as do many other musics), what is needed is an understanding of how these sonic properties mobilize bodies in shared styles of movement and feeling. While this discussion has made strides toward this aim, further studies on these embodied musical processes and the affects they create will be an especially valuable undertaking.

Works Cited

Berliner, Paul F. 1994. Thinking in Jazz: The Infinite Art of Improvisation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Brinkema, Eugenie. 2014. The Forms of the Affects. Durham: Duke University Press.

Butler, Mark J. 2006. Unlocking the Groove: Rhythm, Meter, and Musical Design in Electronic Dance Music. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Danielson, Virginia. 1997. The Voice of Egypt: Umm Kulthūm, Arabic Song, and Egyptian Society in the Twentieth Century. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

De Souza, Jonathan. 2017. Music at Hand: Instruments, Bodies, and Cognition. New York: Oxford University Press.

Durkheim, Émile. 1915. The Elementary Forms of Religious Life: A Study in Religious Sociology. Translated by Joseph Ward Swain. London: G. Allen & Unwin/Macmillan.

Farraj, Johnny, and Sami Abu Shumays. 2019. Inside Arabic Music: Arabic Maqam Performance and Theory in the 20th Century. New York: Oxford University Press.

Frishkopf, Michael. 2001. “Tarab (“Enchantment”) in the Mystic Sufi Chant of Egypt.” In Colors of Enchantment: Theater, Dance, Music, and the Visual Arts of the Middle East, edited by Sherifa Zuhur, 233–69. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press.

Garcia, Luis-Manuel. 2020. “Feeling the Vibe: Sound, Vibration, and Affective Attunement in Electronic Dance Music Scenes.” Ethnomusicology Forum 29 (1): 21–39.

Grant, Roger Mathew. 2020. Peculiar Attunements: How Affect Theory Turned Musical. New York: Fordham University Press.

Hasty, Christopher F. 1997. Meter as Rhythm. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kozak, Mariusz. 2020. Enacting Musical Time: The Bodily Experience of New Music. New York: Oxford University Press.

Leys, Ruth. 2011. “The Turn to Affect: A Critique.” Critical Inquiry 37 (3): 434–72.

Massumi, Brian. 2002. Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation. Durham: Duke University Press.

Monson, Ingrid. 1996. Saying Something: Jazz Improvisation and Interaction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Qureshi, Regula Burckhardt. 1986. Sufi Music of India and Pakistan: Sound, Context and Meaning in Qawwali. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Racy, Ali Jihad. 1991. “Creativity and Ambience: An Ecstatic Feedback Model from Arab Music.” The World of Music 33 (3): 7–28.

Racy, Ali Jihad. 2003. Making Music in the Arab World: The Culture and Artistry of Ṭarab. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schutz, Alfred. 1977. “Making Music Together: A Study in Social Relationship.” In Symbolic Anthropology: A Reader in the Study of Symbols and Meanings, edited by Janet L. Dolgin, David S. Kemnitzer, and David M. Schneider, 106–19. New York: Columbia University Press.

Shannon, Jonathan H. 2003. “Emotion, Performance, and Temporality in Arab Music: Reflections on Tarab.” Cultural Anthropology 18 (1): 72–98.

Shannon, Jonathan H. 2006. Among the Jasmine Trees: Music and Modernity in Contemporary Syria. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.

Shelley, Braxton D. 2019. “Analyzing Gospel.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 72 (1): 181–243.

Straus, Joseph N. 2003. “Uniformity, Balance, and Smoothness in Atonal Voice Leading.” Music Theory Spectrum 25 (2): 305–52.

Toussaint, Godfried T. 2013. The Geometry of Musical Rhythm: What Makes a “Good” Rhythm Good? Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Turino, Thomas. 2008. Music as Social Life: The Politics of Participation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Witek, Maria A. G. 2017. “Filling In: Syncopation, Pleasure and Distributed Embodiment in Groove.” Music Analysis 36 (1): 138–60.

Media Sources

Abdel Halim Hafez - [عبد الحليم حافظ]. “Abdel Halim Hafez - Zay El Hawa[عبد الحليم حافظ - زى الهوا] .” YouTube. August 12, 2015. Video, 38:35. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ARaIrRuxXdA.

Al-Safi, Fakhri, Shaheen - Topic. “Ya Maali [']sh-Shaam.” YouTube. March 2, 2014. Video, 6:40. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lxrcDOqL3Io.

National Arab Orchestra. “National Arab Orchestra - Alf Leila wi Leila / [الف ليلة وليلى] – Mai Farouk / [مي فاروق].” YouTube. June 12, 2020. Video, 16:28. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q_HoGYhk4x8.

National Arab Orchestra. “National Arab Orchestra - Ghanili Shway - Mai Farouk & Lubana Al Quntar / [القنطار] [مي فاروق و لبنة].” YouTube. February 26, 2021. Video, 9:06. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JAFTuss-Ekw.

Sayed Darwish - Topic. “Ya Bahjet Errouh.” YouTube. April 15, 2016. Video, 1:14. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XlhKY1ivRlo.