Introduction

Two monographs delving into eighteenth-century sonata forms—L. Poundie Burstein’s Journeys Through Galant Expositions and Yoel Greenberg’s How Sonata Forms: A Bottom-Up Approach to Musical Form—arrive at a time when the majority of new Formenlehre discourse centers Romantic form. This is due, in no small part, to the fact that many of the prominent analysts of musical form today are preoccupied with the long nineteenth century: Julian Horton, Anne Hyland, Janet Schmalfeldt, Benedict Taylor, and Steven Vande Moortele, for example, are primarily concerned with excavating formal processes in music composed during this period. Indeed, all have published at least one monograph and multiple articles that engage predominantly with nineteenth-century music since 2011: for example, Horton (2015, 2017, and 2022); Hyland (2016 and 2023); Schmalfeldt (2011); Taylor (2011 and 2021); Vande Moortele (2017 and 2021). While my own work has largely been situated in the nineteenth century and in dialogue with the work of the aforementioned scholars, I found it refreshing to engage with new (to me) repertoire, much of which predates the advent of a textbook “sonata form,” through Burstein’s and Greenberg’s analyses. My contributions to the new Formenlehre include Martinkus (2017, 2018, 2021). Moreover, I felt a kinship with these scholars of the eighteenth century as they reckoned with the awkward fit between contemporary theories of form and historical practice. For more on issues that arise in applying theories of Classical form to the analysis of Romantic music, see Horton (2017).

In their respective studies, Burstein and Greenberg engage with a large swath of repertoire. In so doing, they implicitly communicate the value of moving beyond the canon—a trend echoed in both scholarship of Romantic form, specifically, and in the discipline of music theory, more broadly. With regards to Romantic form, Horton, Taylor, and Vande Moortele—through their ongoing corpus study, “Theorizing Sonata Form in European Concert Music, 1815–1914”—aim to develop a more nuanced understanding of sonata-form composition in the nineteenth century through analyses of ca. 1300 pieces, including works both canonic and otherwise. As an external collaborator, I have found it gratifying to center composers and pieces previously underrepresented in the discourse. Ultimately, these monographs complement one another quite well: their approach to framing and interpreting analyses paints a more comprehensive picture of compositional thought and practice in the eighteenth century than perhaps either book achieves alone. In what follows, I consider each work in turn and close by placing the two texts in dialogue, considering how these studies impact future contributions to the new Formenlehre.

Journeys Through Galant Expositions

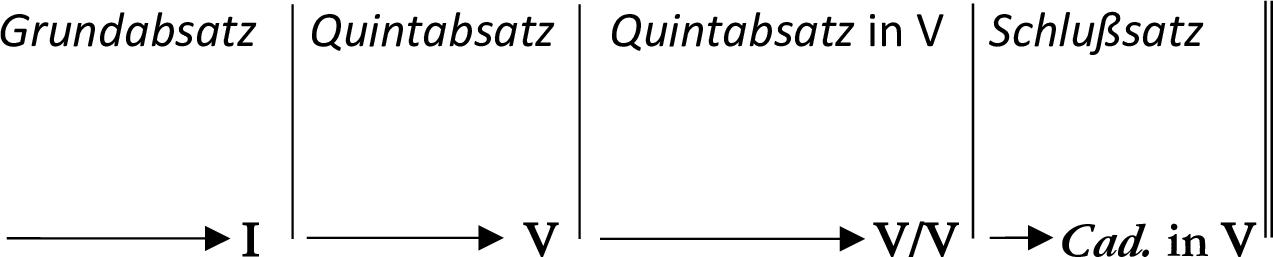

Burstein’s monograph focuses on Galant sonata forms which, for him, means pieces composed between 1750 and 1780 (11). The book has two large-scale parts: chapters 1–6 introduce the reader to historical terms and analytical methods through a thorough review of the writings of multiple eighteenth-century theorists (e.g., Koch, Galeazzi, Kollman, and Neubauer), placing these theories in dialogue with modern terminology, while chapters 7–15 demonstrate theoretical concepts via detailed analysis. There is also a companion website, which is a fantastic resource filled with annotated scores and links to recordings. However, it can be somewhat disappointing when links to recordings no longer work (e.g., examples 7.3f, 7.3k) or measures are missing (e.g., 7.3d). As a primer on theories of form in the eighteenth century—and an especially deep dive into Koch’s formal theory—the first half of this text, and the glossary included in Appendix II, could slot well into any history of theory course. It is clear from Danuta Mirka’s review that she disagrees with some of Burstein’s interpretations of Koch’s theory. For example, she takes issue with Burstein’s explication of the distinction between a Grundabsatz, Cadenz, and förmliche Cadenz (Mirka 2022, 273–79). However, if read in conjunction with Koch, exploring these different interpretations of historical writings could be a useful pedagogical exercise. For analysts of eighteenth-century sonata forms, the standard punctuation sequence, which is formally introduced in chapter 7 and summarized here in Example 1 presents a useful heuristic for understanding the construction of Galant expositions.

Chapter 7 lays the framework for the analyses of expositions presented in chapters 8–13. Chapter 8 illustrates what modern theorists might consider standard, two-part expositions with clearly defined “zones” (136); chapters 9–13 explore different ways of dividing the exposition into two or three parts; and chapters 14–15 look beyond expositions to the last two Theile and full movements, respectively. Throughout chapters 7–13, the punctuation sequence is Burstein’s primary analytical tool. Each exposition analyzed is parsed into “legs” on their respective journeys to resting points on I, V, V of the subordinate key, and a final PAC in the subordinate key. In the text, Burstein comingles the Kochian language of various Sätze with modern terminology drawn from Hepokoski and Darcy’s sonata theory (e.g., “medial caesura” and “secondary theme”). My use of the term “subordinate key” here conveys my alignment with the form-functional analytical perspective of William Caplin (Caplin 1998). This analytical attitude certainly influenced my engagement with Burstein’s analyses, especially the extent to which I am able to hear or privilege the punctuation sequence in my own listening. For Burstein, the benefits of the punctuation sequence stem not only from its seemingly ubiquitous presence in Galant expositions, but also from its ability to cleanly capture motion towards harmonic goals without incurring the baggage associated with modern terminology. The first two examples in chapter 7, and the subsequent form charts provided in ex. 7.3, all serve to illustrate “the underlying punctuation sequence” which is “very vivid” (127). Burstein contrasts this clear articulation of the punctuation sequence with the difficulty one might encounter when approaching these works from a modern perspective: “what is not easy to determine for the expositions cited in Ex. 7.3, however . . . are the locations—even in an approximate, general sense—of the transition vs. a secondary theme group, or which of the half-cadential breaks should be labeled as the medial caesura” (127).

Each form chart in ex. 7.3 offers an overview of the exposition, aligning groups (delineated by measure numbers) with their location in the punctuation sequence. From listening to these examples, my overall impression is that the punctuation sequence offers a way of listening for arrivals that helps parse formal units. Moreover, I am intrigued by the different grouping structures that result from articulating the same punctuation sequence. Burstein acknowledges this possibility—that the overlay of modern terms will vary from piece to piece even though the punctuation sequence is shared—at the beginning of chapter 7. For example, in the case of 7.3d (Antonio Brioschi, Symphony in G Major, op. 2 no. 59, first movement) the Grundabsatz feels self-contained—likely due to the sol-do motion in the bass in mm. 3–4 and the subsequent closing section rhetoric that follows (see Example 2). At other times, I find myself hearing arrivals in the Grundabsatz as subordinate to subsequent cadential articulations at the end of the Quintabsatz, creating one larger unit. For instance, in 7.3g (Anna Amalia of Prussia, Sonata for Flute and Continuo in F Major, third movement) I hear the Grundabsatz and Quintabsatz grouping together, forming a main theme (cbi + continuation) that ends with a half cadence (see Example 3). I offer select examples of the different grouping structures that arise, but there are certainly more. For example, sometimes the Quintabsatz and Quintabsatz in V group together, as in 7.3e (Domenic Alberti, Sonata for Keyboard in F Major, op. 1 no. 2, first movement). Further excavation of how Absätze group and how this impacts the resulting expositional layout would be an interesting line of inquiry, building on Burstein’s work.

As indicated by the title, in Journeys Through Galant Expositions Burstein urges the reader and future analyst to think of formal sections as goal-directed units, motivated by the motion from a starting point towards a specific harmonic goal. Burstein juxtaposes this journey metaphor with the predominant “container” model of form (5–10) and demonstrates through multiple analyses that while the “outlines of distinct first theme, transition, and secondary theme sections” may be “murky,” the punctuation sequence underpinning the construction of many Galant expositions is “unambiguous” (123). This theme—the thorny relationship between contemporary models of form and pieces written in the Galant style—runs throughout the text.

Throughout the analytical chapters, Burstein routinely highlights how Galant expositions thwart facile classification using the terminology of contemporary formal units (especially the distinction between transition and subordinate theme). However, there are instances where, while the distinction between transition and subordinate theme is blurry, a “distinction” (or functional lack thereof) can be drawn if one attends to intrinsic functions within formal units. For example, in 7.3p (Joseph Haydn, Symphony no. 1 in D Major, third movement), I hazard to guess that Burstein would call the boundary between TR and ST hard to distinguish. He identifies the end of the Quintabsatz in m. 15, eliding with a Schlusssatz comprising mm. 15–21. I hear this passage as indicative of transition/subordinate theme fusion: what could have been a standing on the dominant in mm. 15ff, clearly marking the end of the transition, instead initiates a continuation phrase leading to a V: PAC in m. 21 (fusing transition and subordinate theme function, with no clear beginning to the subordinate theme and in retrospect undermining the end of the transition; this entire unit is followed by subordinate theme 2 in mm. 21–32). For more on the concept of transition/subordinate theme fusion, see Caplin and Martin (2016). Much of this is due, in Burstein’s view, to the fact that analysts today simply approach sonata form from a different perspective than Koch et al.: thematic character does not seem to play a large role in theorizing sectional divisions within Galant expositions, and eighteenth-century theorists were more concerned with tonal motion and melodic/harmonic goals than with key areas writ large (87). This can result in two drastically different conceptualizations of, for instance, the division of an exposition into two parts. In an exposition with a modulating transition, as shown in his ex. 4.10, Burstein suggests that what contemporary theorists would call the transition + subordinate theme, Koch would group together in the second half. This stands in stark contrast to a contemporary parsing, in which the transition (by dint of being a transition)—regardless of the key in which it cadences—belongs to the first half of the exposition (76). While in the abstract, Burstein’s parsing makes sense, it does not account for all possible interpretations (especially situations with transition/subordinate theme fusion, as discussed in note 10, which seem to be relatively common in this repertoire).

The discomfort conveyed in Burstein’s prose, describing his experience applying modern terminology, is not relegated to the analysis of Galant sonata forms. I recently encountered a piece by Helene Liebmann (Grand Piano Sonata in C Minor, op. 3, first movement), published in 1811, that does not “play nice” with contemporary formal labels. This is not to say that you cannot make sense of it through a modern lens. However, the parallels between Liebmann’s piece and the standard punctuation sequence struck me: considering the cadences that end large-scale units, we find arrivals on V – V/III – I/III (x2), suggesting perhaps a deeper-level connection to eighteenth-century models of punctuation form. All of this to say, while readers (such as myself) may initially have difficulty hearing genuine points of arrival within the punctuation sequence, it offers another productive mode of listening to pieces from the Galant era and beyond.

How Sonata Forms

The title of Greenberg’s monograph, much like Burstein’s, is apropos. Interested quite literally in how sonata form came to be, Greenberg derives a bottom-up theory of sonata form from a corpus of 732 works composed between 1656–1769, drawing parallels between the evolution of genes and musical form. There are two distinct corpora represented in the book. The first, pertaining directly to sonata form, are the 732 pieces written between 1656–1769; findings from the analysis of this corpus are covered in chapters 4–6. The second corpus comprises 240 concerto movements composed between 1720–1790, and these are addressed in chapter 7. For Greenberg, the medial repeat, double return, and end rhyme are musical/cultural phenomena that, through replication, coalesced into one of the most significant musical-cultural artifacts of the eighteenth century: sonata form. Of note, the double return and end rhyme were more successful at replication in the long run than the medial repeat. Unlike Burstein’s monograph, this book is less about presenting an historical perspective to new readership (although Greenberg does engage with eighteenth-century theorists at times), and more about rethinking our relationship to sonata form as analysts. That is, Greenberg aims to shed new light on the ontological status of the thing itself.

Chapters 1–2 review multiple twentieth-century theorizations of sonata form, such as Ratner (1980), Rosen (1980), Caplin (1998), and Hepokoski and Darcy (2006). Two threads emerge in these opening chapters that set the stage for the remainder of the text. The first concerns fundamental stumbling blocks Greenberg identifies in modern theorizations of sonata form. He refers to these as the synchronic and diachronic problems—for Greenberg, “sonata form is thus the victim of a twofold fuzziness: synchronic fuzziness in our inability to clearly define and delineate it, and diachronic fuzziness in our inability to agree on its advent” (23). The second thread excavates the relationship between parts and wholes, and the general tendency in theorizing to privilege the whole: “we engage with a sonata form without a second theme in the dominant, without a recapitulated second theme, or without a double return as we would engage with a headless man: we must either explain why the part has gone missing or else . . . provide the whole with an entirely different categorization” (37). This monograph aims to solve these problems, theorizing from a position that not only appeals to both synchronic and diachronic concerns, but also works “bottom up” to prioritize parts over wholes.

Chapter 3 introduces the lens of evolutionary biology, and Greenberg situates his bottom-up theory of musical form in within the mid-twentieth-century turn towards a gene-centered theory of natural selection. From a biological perspective, the gene becomes the primary unit of natural selection; humans, animals, and plants are “survival machines” for genes. Thus, sonata form becomes the “survival machine” for independent elements found within (the specific elements are introduced in chapter 4). In both cases, the success of a mutation is measured in statistical terms. Couching his theory of form in terms of evolution, Greenberg appeals frequently to Richard Dawkins’s work, particularly his contributions to reorienting the evolutionary narrative around genes rather than organisms. Notably, Dawkins’s work on the emergence and replication of cultural phenomena (memes) offers a strong grounding for the parallelism Greenberg draws between the evolution, through imitation, of a cultural artifact (sonata form) and the gene’s capacity to propagate (Dawkins 1976, 249). Greenberg engages relatively minimally with the literature on memes; future work, building on this study, could investigate the relationship between cultural context and the medial repeat, double return, and end rhyme.

Chapter 4 gets to the heart of Greenberg’s theory, detailing the current “genes” under consideration: the medial repeat, the double return, and the end rhyme. Summarized here are the analyses of 732 movements composed between 1656–1769 containing binary repeat signs, set in moderate to fast tempi, by eighty-four composers born and active in Germany, Austria, and Italy (67). For more details of the corpus, such as the works included (listed alphabetically and chronologically), the ratio of works to composers, and distribution of composers by decade, one can consult the appendices and companion website. Greenberg concludes that the three aforementioned elements are statistically independent and become more popular over time, supporting his theory of sonata form as an emergent phenomenon. Throughout the chapter Greenberg places his data in dialogue with eighteenth-century theories of sonata form, illustrating a closer relationship between theory and practice in historical compared to modern theories of form. For example, in Greenberg’s corpus the medial repeat peaks in the 1740s and declines through the 1760s. Yet it isn’t until 1739—close to the peak—that the medial repeat is explicitly mentioned in a theoretical text. By 1793, though other options for beginning the second part are discussed, the medial repeat it is still positioned as the “first-level default” (69). By 1796 the medial repeat “is considered tedious and outdated” (71), well after it had started to fall out of favor compositionally. The relationship between roughly contemporaneous theory and practice stands in stark juxtaposition to modern theories of form, where the medial repeat is listed as one of multiple ways to initiate the development section. The narrative presented in this chapter (through data) is convincing—that is, it seems reasonable that what we think of as sonata form arose from a confluence of events and had been around for some time before earning its own name, distinct from other binary or ternary forms.

Chapters 5 and 6 center positive and negative interactions, respectively. Positive interactions occur when two items together are better than they are alone; being paired thus “increases their survival fitness” and leads to a common practice in the realm of musical form (97). Negative interactions occur when two elements compete or contradict one another; in these situations, one element will prevail over the other (116). Chapter 5 is concerned with timelines; specifically, Greenberg uses data to tease apart when a piece that looks like a sonata form is best understood to have arisen out of chance as opposed to belonging to sonata form as a formal category. He considers two structures: those with a “binary rotation”—referred to as a type 2 sonata by Hepokoski and Darcy (2006, 353–87)—and those with recapitulatory rotations, or type 3 sonata forms (Hepokoski and Darcy 2006, 344). Greenberg first explains the rise of the binary rotation, locating its “emergence . . . as a unified, higher-martinkusarchy phenomenon” in the 1720s and 1730s, when the medial repeat and end rhyme occurred frequently together and requoted increasingly more material (100). Following the data, the recapitulatory rotation (as a unit in-and-of itself) emerged between 1740 and 1760. Through a comparison of two keyboard sonatas by C. P. E. Bach, one from 1744 (Sonata in C Major, Wq. 62 no. 7), the other from 1757 (Sonata in B♭ Major, Wq. 62 no. 16), Greenberg illustrates this emergence. The double return in the C Major Sonata is followed by nearly twenty measures not explained vis-à-vis rotational logic before realigning with the exposition, while the B♭ Major Sonata’s “post double-return space” is clearly a recapitulatory rotation. Through his discussion of the recapitulation’s emergence in the late eighteenth century, Greenberg calls attention to the misattribution of terms like “false recapitulation” and “secondary development” when used in the analysis of such Galant sonata forms: doing so frames normative practices ca. 1740 as deviations from a norm that didn’t arise until much later. This stance affirms the work of other eighteenth-century scholars (e.g., Neuwirth 2013, Burstein 2020), and highlights the issues that arise when using a model derived from the high Classical style to analyze Galant music. Chapter 6 illustrates combinations of elements that did not coalesce into a higher-level formal unit. Specifically, Greenberg addresses how composers avoided an abundance of repetition while employing both a medial repeat and double return. While the double return was to become the primary marker of sonata form (eclipsing the early prominence of the medial repeat), this chapter explores compositional solutions to using both a medial repeat and a double return, presented in order from more “binary-oriented structures to ternary-oriented ones” (120). Taken together, these two chapters showcase the dynamic, processual (or, in Greenberg’s terms, emergent or evolutionary) nature of form.

Chapters 7 and 8 move beyond sonata form proper. Chapter 7 tackles the concerto, using data from a similarly large corpus (250 works composed between 1720–1790) to illustrate the transition from a structure based on the alternation of opposing textures (tutti versus solo) to a more sonata-like structure resulting from the form’s gradual expansion accompanied by a shift in agency away from orchestral tutti to the solo instrument. Tracing the same three “genes”—medial repeat, double return, and end rhyme—Greenberg illustrates the convergence of sonata and concerto form over the course of the eighteenth century. Chapter 8 concludes the monograph, summarizing Greenberg’s contribution to unpacking the emergence of sonata form (pp. 184–185, especially), suggesting paths of future study (adopting the genealogical model to study other forms, such as fugue), reinforcing the fuzziness of categories, and reminding the reader how much our analytical models influence the way we think.

Throughout the book, there is ample critique of twentieth-century theories of form and of how contemporary theorists approach formal analysis. These critiques stem from the belief that modern theorists are overly reliant on one model of sonata form that is too narrow. Greenberg is by no means alone in this regard. Indeed, the desire for a theory of Romantic form stems from a similar concern to escape the inherent “negative” theorizing that occurs when comparing individual works against abstract formal models (especially models derived from music composed in a limited time period). For more on “positive” versus “negative” approaches to analyzing nineteenth-century form see Vande Moortele (2013, 408). Greenberg offers a different way to think about how sonata form came to be, and he makes the convincing argument that analysts would do well to think about the context of a piece before engaging in a norms-versus-deformations dialogue. It bears mentioning, however, that Greenberg’s bottom-up theory is not an analytical tool, which might leave the reader who is hoping to duplicate some of Greenberg’s analyses with questions. For example, I would have appreciated more clarity in defining what counts as a medial repeat or double return: how much material needs to return, and how loosely related can it be? That said, Greenberg is not presenting an analytical method; rather, he offers an interpretive framework for historically contextualizing sonata forms.

From How to Now: A Journey Forward

Read together, Journeys Through Galant Expositions and How Sonata Forms offer a robust picture of sonata-form composition in the mid-eighteenth century, introducing the reader to a great deal of new repertoire from complementary perspectives. For example, Burstein focuses primarily on the first part (exposition), while Greenberg highlights the second part (and how it can support a binary or ternary structure). Both present findings from analyzing large swaths of music, moving beyond the typical composers consulted in contemporary theories of form: Burstein’s monograph is invested in reviving an analytical system for the Galant style and offers the reader a slew of examples to engage with, while Greenberg takes a more historically oriented tack, demonstrating how those structures came to be primarily through statistical analysis. For the reader wary of engaging with a potentially math-laden text, it is worth noting that Greenberg does a nice job of commingling the explication of mathematical components/statistical method with digestible descriptions of the results—including the occasional note telling the less math-inclined what to skip. These authors both engage with historical theories of form, but for different reasons: Burstein uses the methods developed by Koch and others to offer a different framework for analysts, while Greenberg compares descriptions of sonata form found in treatises with trends in his data, mapping changes in his findings onto changes in theoretical discourse.

I suggested in the introduction that these studies can impact future contributions to the new Formenlehre and strongly believe this to be true. These texts reinvigorate the conversation surrounding form in the eighteenth-century; future research building on these works could interrogate the relationship between formal functions and the punctuation sequence, or adopt Greenberg’s genetic model to other formal types. They also highlight the risks involved when using contemporary models to analyze historical practice. Burstein reminds us that, while analytical anachronisms can be valid and useful, our analyses stand to benefit when we place our models in dialogue with historically contemporaneous writings. The issue of anachronism manifests in Greenberg’s work as the diachronic problem. Tackling it head-on, as shown in his text, can enrich analyses and help ensure that, in an effort to label musical phenomena, analysts do not conflate musical object with compositional intent. Taken together, these monographs serve as healthy reminders to analysts that sonata form has never been monolithic and should not be treated as such.

Works Cited

Burstein, Poundie L. 2020. Journeys through Galant Expositions. New York: Oxford University Press.

Caplin, William E. 1998. Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. New York: Oxford University Press.

Caplin, William E., and Nathan John Martin. 2016. “The ‘Continuous Exposition’ and the Concept of Subordinate Theme.” Music Analysis 35 (1): 4–43.

Dawkins, Richard. 1976. The Selfish Gene. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Greenberg, Yoel. 2022. How Sonata Forms. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hepokoski, James and Warren Darcy. 2006. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata. New York: Oxford University Press.

Horton, Julian. 2015. “Formal Type and Formal Function in the Postclassical Piano Concerto.” In Formal Functions in Perspective: Essays on Musical Form from Haydn to Adorno, edited by Steven Vande Moortele, Julie Pedneault-Deslauriers, and Nathan Martin, 77–122. Rochester: University of Rochester Press.

Horton, Julian. 2017. “Criteria for a Theory of Nineteenth-Century Sonata Form.” Music Theory and Analysis 4 (2): 147–91.

Horton, Julian. 2022. “First-Theme Syntax in Brahms’s Sonata Forms.” In Rethinking Brahms, edited by Nicole Grimes and Reuben Phillips, 195–228. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hyland, Anne. 2016. “In Search of Liberated Time, or Schubert’s Quartet in G Major, D. 887: Once More Between Sonata and Variation.” Music Theory Spectrum 38 (1): 85–108.

Hyland, Anne. 2023. Schubert’s String Quartets: The Teleology of Lyric Form. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Martinkus, Caitlin. 2017. “The Urge to Vary: Schubert’s Variation Practice from Schubertiades to Sonata Forms.” PhD diss., The University of Toronto.

Martinkus, Caitlin. 2018. “Thematic Expansion and Elements of Variation in Schubert’s C Major Symphony, D. 944/i.” Music Theory and Analysis 5 (2): 190–202.

Martinkus, Caitlin. 2021. “Schubert’s Large-Scale Sentences: Exploring the Function of Repetition in Schubert’s First-Movement Sonata Forms.” Music Theory Online 27 (3).

Mirka, Danuta. 2022. Review of Journeys Through Galant Expositions by L. Poundie Burstein. Journal of Music Theory 66 (2): 273–79.

Neuwirth, Markus. 2013. “Surprise Without a Cause.” Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Musiktheorie 2: 259–91.

Ratner, Leonard G. 1980. Classic Music: Expression, Form, and Style. New York: Schirmer Books.

Rose, Charles. 1980. Sonata Forms. New York: W. W. Norton.

Schmalfeldt, Janet. 2011. In the Process of Becoming: Analytic and Philosophical Perspectives on Form in Early Nineteenth-Century Music. New York: Oxford University Press.

Taylor, Benedict. 2011. Mendelssohn, Time and Memory: The Romantic Conception of Cyclic Form. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Taylor, Benedict. 2021. “Clara Wieck’s A Minor Piano Concerto: Formal Innovation and the Problem of Parametric Disconnect in Early Romantic Music.” Music Theory and Analysis 8 (2): 215–43.

Vande Moortele, Steven. 2013. “In Search of Romantic Form.” Music Analysis 32 (3): 404–31.

Vande Moortele, Steven. 2017. The Romantic Overture and Musical Form from Rossini to Wagner. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vande Moortele, Steven. 2021. “Apparent Type 2 Sonatas and Reversed Recapitulations in the Nineteenth Century.” Music Analysis 40 (3): 501–33.