Introduction

Tonal contemporary art music has received little attention from music theorists despite its popularity with performers and audiences. Even notable exceptions such as Harrison 2016 and Lam 2019 focus on the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth, leaving much room for work on more recent repertoire. This category includes works by Eric Ewazen (b. 1954), an American based in New York City praised for his “approachable, cosmopolitan style” (Brown 2009, 140). Ewazen’s popularity partially stems from his emphasis on accessibility for performer and audience, his concern for using each instrument to its best advantage, and his attention to instruments that welcome new repertoire, particularly winds and brass; see Pettit (2003, 34–35) and Brown (2009, 137). While writings on his music include a handful of DMA documents and abundant interviews, analyses of his works have yet to appear in professional music theory venues. This paucity of analyses may partially stem from the fact that, as Ryan Anthony observes, “[m]uch of Ewazen’s music looks easy and less sophisticated than it proves to be” (Pettit 2003, 38). His output divides almost evenly into programmatic and non-programmatic works. The latter includes compositions in traditional genres such as concertos and sonatas. HipBoneMusic (2017, 24:00–24:55). For a works list, see the “Music” page of Ewazen’s website: https://www.ericewazen.com/themusic.php. Much of the fascination of his music stems from deft interweaving of techniques garnered from a wide array of nineteenth- and twentieth-century styles into his own recognizable voice.

Selecting one work as a case study, this article examines influences on form and tonality in Ewazen’s Sonata No. 1 for Flute and Piano. Borrowing Ian Bates’ general definition, “tonality” in this article denotes “a scale with identifiable tonic from which melodic and harmonic materials are derived” (2012, 35, fn 9). The composition was written for Marya Martin in 2010 and premiered in 2011. In his preface, Ewazen (2011) notes the piece is “designed in the great tradition of late 19th century instrumental sonatas.” Motivic development plays a large role in this work, in keeping with that legacy. Some aspects of large-scale form likewise reflect classical and romantic models: the three movements are in sonata, ternary, and five-part rondo form respectively. The tonal designs within these frameworks, however, reflect more recent models. Modal mixture pervades the work, invoking not only major and minor but also many diatonic modes. His harmonic language reflects the influence of folksong, impressionism, film, and pop/rock. Sections and even movements no longer rely on principles of tonal closure, forging other means of crafting tonal narrative.

Such convergence of diverse elements demands an eclectic analytic approach. Part I of this article establishes context, identifying Ewazen’s main influences and the corresponding tools for analysis. Part II of this article analyzes each movement of Sonata No. 1 for Flute and Piano in turn. The attraction of Ewazen’s music—as with other contemporary tonal music—partially stems from the expressive interweaving of multiple nineteenth- and twentieth-century influences, as Ewazen’s style in general and this sonata in particular illustrate.

Part I: Context and Approach

I have really embraced tonality as my main voice. I always have tonal centers, and somewhat traditional harmonic progressions, although this is filtered through a world of modal music, and the utilization of all those early 20th century scales such as the pentatonic and octatonic. I don’t use key signatures, which allows a freedom of movement from key to key, but there is always a tonal center to my music. . . . I have used atonality, but I use it more for effect or for passages that require a certain amount of intensity. . . . My meters tend to be along the lines of the early 20th century composers—often stable, but sometimes using mixed meters as well (Ewazen in Madden 2002, 139–140).

Ewazen’s summary above highlights several characteristics of his writing. First, his conception of tonality entails hierarchic stability around a single local pitch within a scale. This may or may not entail functional progressions and may or may not venture beyond major and minor scales to include diatonic modes and other recognized collections including pentatonic, octatonic, and whole tone. Thus, Ewazen’s view of “tonality” aligns with Ian Bates’ (2012) definition mentioned above. For a summary of the numerous other ways the term has been used over the centuries, see Hyer (2001). Second, forgoing the use of key signatures facilitates rapid and frequent changes between tonalities, which may alter the tonic pitch, the collection of pitches, and/or the rotation of the pitch collection. Third, truly atonal passages, which obscure any sense of a reference pitch, rarely surface in his music. Fourth, meter is nearly always clearly articulated, regardless of whether the passage features only a simple or compound meter or entails complex or changing meters. Fast movements frequently feature shifting meters and a rhythmic vitality Ewazen attributes to the Eastern European folk tunes he learned as a child from his immigrant parents. His mother was Polish, and his father was Ukrainian. References to his father’s interest in Ukrainian dancing are ubiquitous in Ewazen’s interviews, including Brown (2009, 138) and HipBoneMusic (2017, 3:35–4:28).

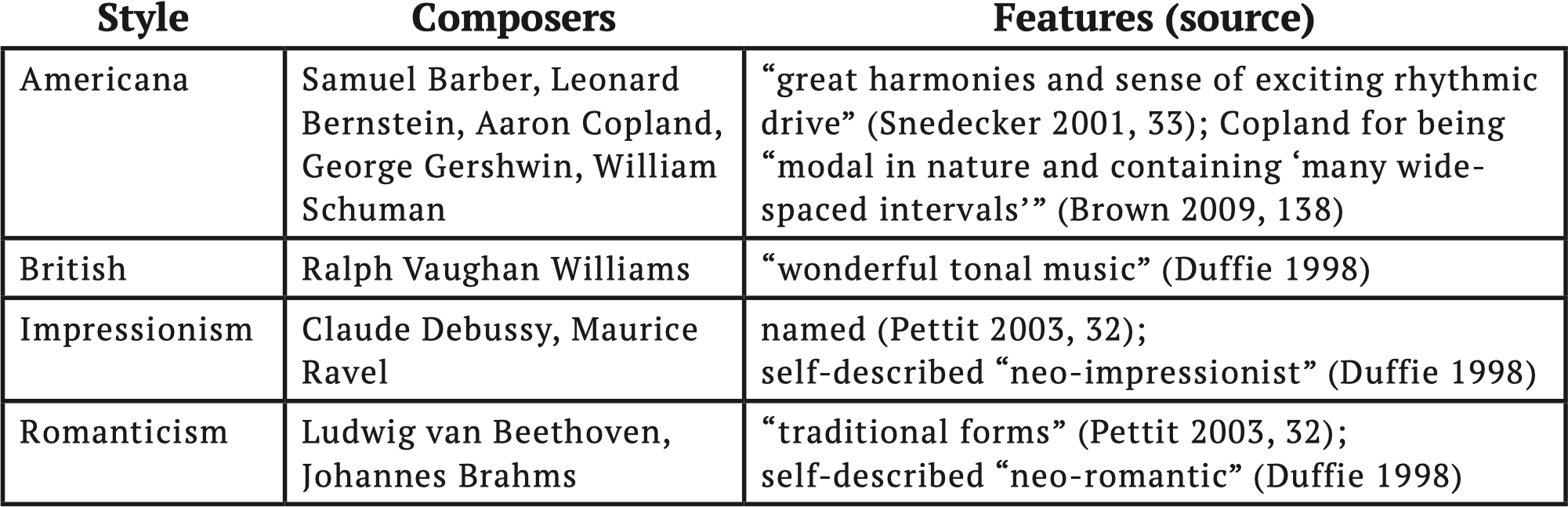

Most of these musical traits appear in the works of composers from decades or even centuries prior, as Ewazen has readily acknowledged in numerous interviews. As Sigrun B. Heinzelmann (2011, 143) observes of Ravel, Ewazen seems to be a “composer arguably with little overt ‘anxiety of influence.’” Example 1 sorts some of the specific nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century composers Ewazen admires based on style. Ewazen also frequently mentions his teachers as major influences. These include professors Joseph Schwanter, Samuel Adler, Warren Benson, and Eugene Kurtz at Eastman; Gunther Schuller at Tanglewood; and Milton Babbitt at Juilliard. See McNally (2008, 2–10) for a discussion of Ewazen’s formative years. The remainder of this section considers portions of this list as well as the additional contributions of rock and film. The diverse influences on Ewazen’s approach to form, tonality, and harmony require equally diverse analytic tools to highlight the joyous subtleties of his music.

Many aspects of Ewazen’s style reference the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, including elements of form, melody, and motivic development. As Evan Feldman (2015) observes, Ewazen’s “neo-classical sensibilities are reflected in a fondness for symmetrical forms, sonata-allegro movements, and classical titles. He expresses his neo-romanticism in rich harmonies and a theatrical sense of pacing.” While indebted to Beethoven, Ewazen identifies Brahms as his favorite composer, preferring some of the same traits. Interestingly, Ewazen mentions this when discussing the admiration of Brahms held by Milton Babbitt, one of Ewazen’s teachers (HipBoneMusic 2017, 11:33–12:10). Occasionally, the emulation extends past general features. For example, Ewazen consciously modeled his Trio for Trumpet, Violin, and Piano after Brahms’ Horn Trio (Altman 2005, 88). References to traditional forms are common in Ewazen’s music, including the practice of setting the first movement in a multi-movement work as a sonata (Arnone 2016, 32). Ewazen “is especially gifted in the area of writing memorable melodies that unfold organically,” often with tight motivic cohesion (Brown 2009, 137). As Timothy Altman (2005, 136) highlights, “Ewazen’s music is often cyclical. Tonalities, melodies, motives, and rhythms often recur later in the subsequent movements of the same work, giving the listener a sense of unity.”

Given the neo-romantic and/or neo-classical bent of Ewazen’s sonatas, recent Formenlehre provides applicable analytic tools. William Caplin’s (1998; 2009) ideas of formal functions, temporal functions, and the continuum of tight-knit versus loose thematic design prove particularly useful. Occasionally, concepts from James Hepokoski and Warren Darcy’s (2006) Sonata Theory apply, though to a lesser degree due to the modest role of thematic rotation and cadences (especially PACs) in Ewazen’s sonata-form movements. Both sets of tools require flexible implementation, as Ewazen’s approach to form exceeds classical and romantic models in straying from what Edward T. Cone (1968, 76–77) calls the “Sonata principle,” which “requires that important statements made in a key other than the tonic must either be re-stated in the tonic, or brought into a closer relation with the tonic, before the movement ends.” To be fair, not even eighteenth-century works always follow this fuzzy principle, as Hepokoski (2002) illustrates. The point remains that the twentieth and twenty-first centuries illustrate widely divergent ideas of what can constitute a sonata. For instance, Thomas Schmidt-Beste (2011, 157–172) identifies multiple streams in the twentieth century: neo-romanticist, neo-classicist, a return to a “generic piece for instrument(s),” and the eclectic sonata. Even each general category envelops divergent features that resist tidy generalizations.

One of the largest differences in common-practice sonatas and Ewazen’s sonatas revolves around large-scale tonal closure. Both Caplin and Sonata Theory assume tonal closure typical of eighteenth-century works. In Ewazen’s output, however, neither individual movements nor entire works are obligated to start and end in the same tonality, though they may occasionally. For instance, Altman (2005, 18) notes that while each of the eight movements of the chamber work . . . to cast a shadow again starts and ends in different tonalities, the complete work starts and ends in C♯ minor. The fourth movement of that work constitutes a modified ternary, placing the A′ in a different key from that of A (Altman 2005, 51). Joseph McNally III (2008, 34) identifies one motivation for this design: Ewazen “stated that he often does not end in the same key the work or movement begins to hold the interest of the audience.” Naturally, this requires radical adjustments to understanding the role tonality plays in the narrative of Ewazen’s compositions.

Such aspects of Ewazen’s large-scale tonal design find precedent in works by Maurice Ravel. Heinzelmann provides detailed analyses of two applicable examples. In the first movement of the String Quartet (1902–1903), the setting of the secondary theme in the submediant key softens any sense of conflict with the main theme, as in the older precedents in Schubert (2011, 144–159). For further information on Schubert’s approach to sonata form, see Webster (1978). Ravel’s Piano Trio (1914) departs more radically from tonal norms (2011, 160–172). The exposition starts and ends in the same key, introducing both the primary and secondary themes in A minor. Conversely, the movement ends in C major, thus drastically delaying the most typical secondary key to avoid large-scale tonal closure. As Heinzelmann (2011, 173) summarizes, “Ravel entices us to hear and accept the movement as a (double-rotational) sonata form when at the same time he withholds the most central tenet of the sonata principle: the tonic return.” Similarly, Ewazen often evokes sonata form while avoiding tonal norms, most often impacting the movement’s end.

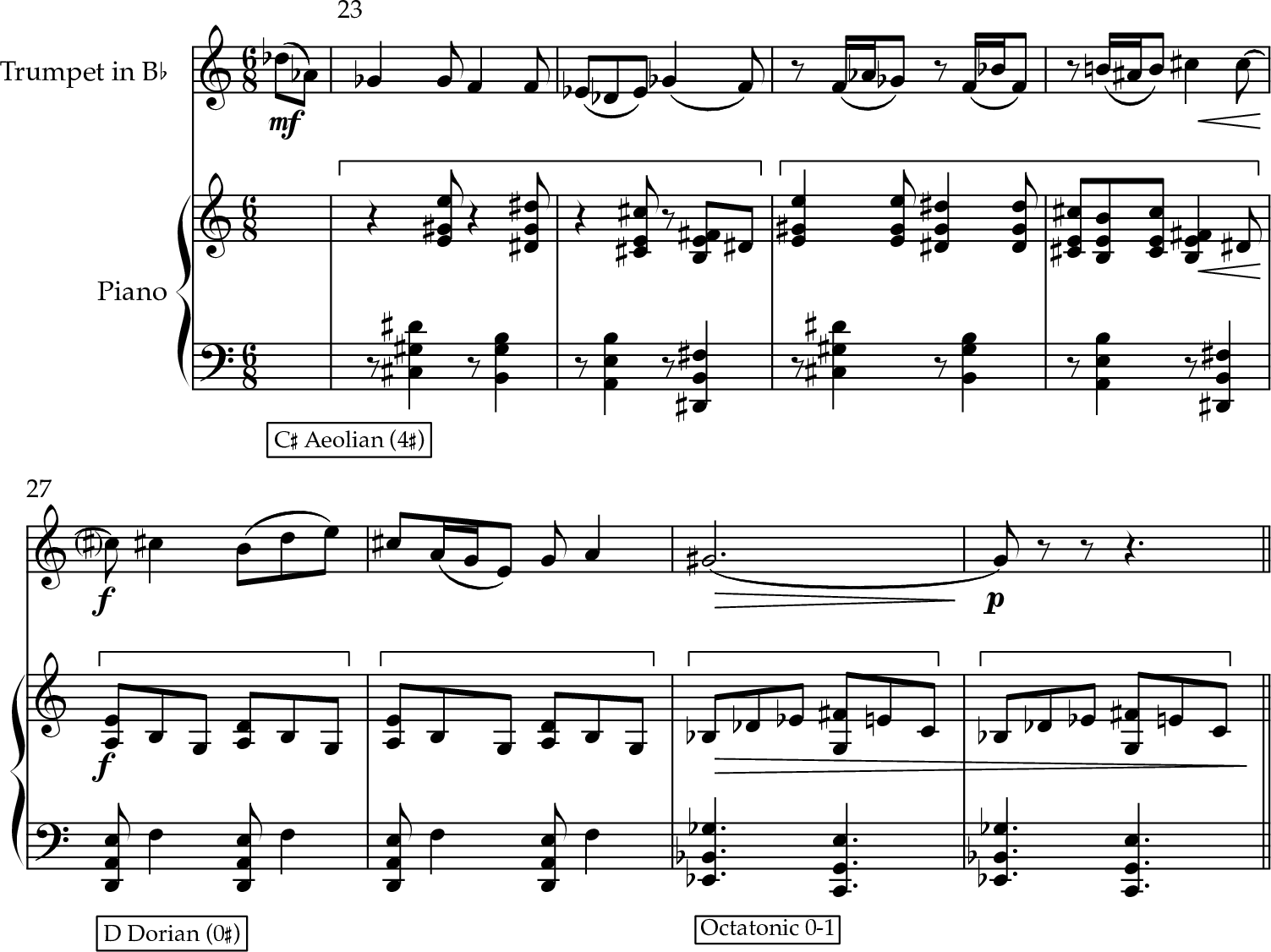

On a smaller scale, Ewazen’s ephemeral shifts between scalar collections recall those of the impressionists, including Ravel as well as Claude Debussy. Most local passages are based on a particular scale or blend of two scales with the same starting pitch, most frequently two modes with adjacent key signatures (like Dorian and Phrygian) or a more thorough mixture of major and minor. Diatonic collections are most frequent, though other collections surface occasionally. For a discussion of octatonic passages in Ewazen’s Sonata for Trumpet and Piano, see McNally (2008, 37–54). Example 2 shows a phrase from the second movement of Ewazen’s Sonata for Trumpet and Piano, which moves through two different diatonic collections and an octatonic collection. Precedents for this appear throughout impressionist compositions, including select movements in sonata form. Resembling aspects of Ravel’s String Quartet mentioned above, the first movement of Ewazen’s trumpet sonata navigates F major, its relative D minor, both whole-tone collections, and all three octatonic collections. Transformations of themes p1 and p2 emphasize some of these scalar shifts (2011, 144–59). This serves as a particular example of what Peter Kaminsky (2011, 108) describes as Ravel’s penchant for “minimal compositional materials serving in maximal formal/structural contexts.” Andrew Aziz (2020) likewise notes scalar shifts in numerous French sonata-form works, including En blanc et noir and L’Isle joyeuse by Debussy as well as the third movement of the Sonatine and “Ondine” from Gaspard de la nuit by Ravel. Such French models prove influential on Ewazen.

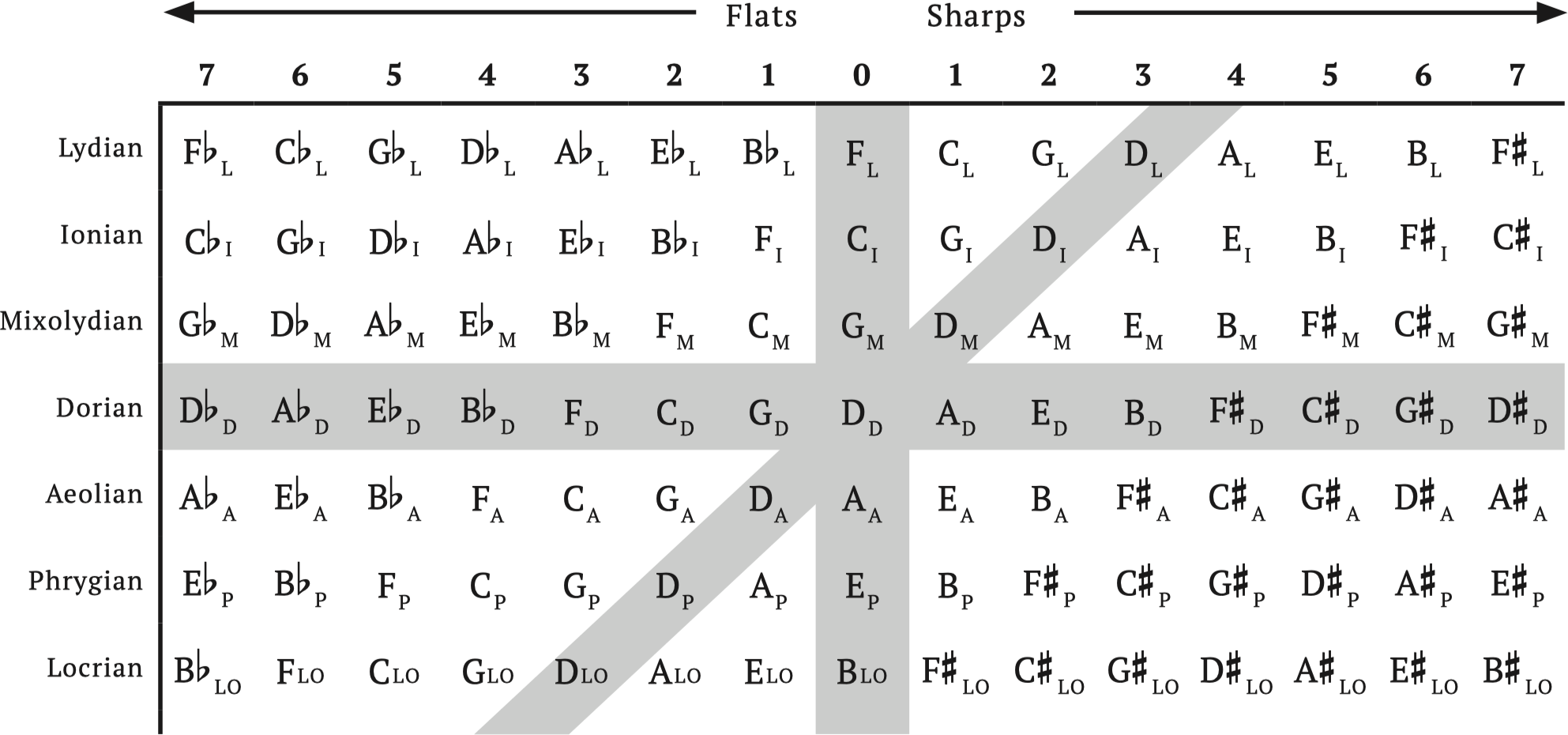

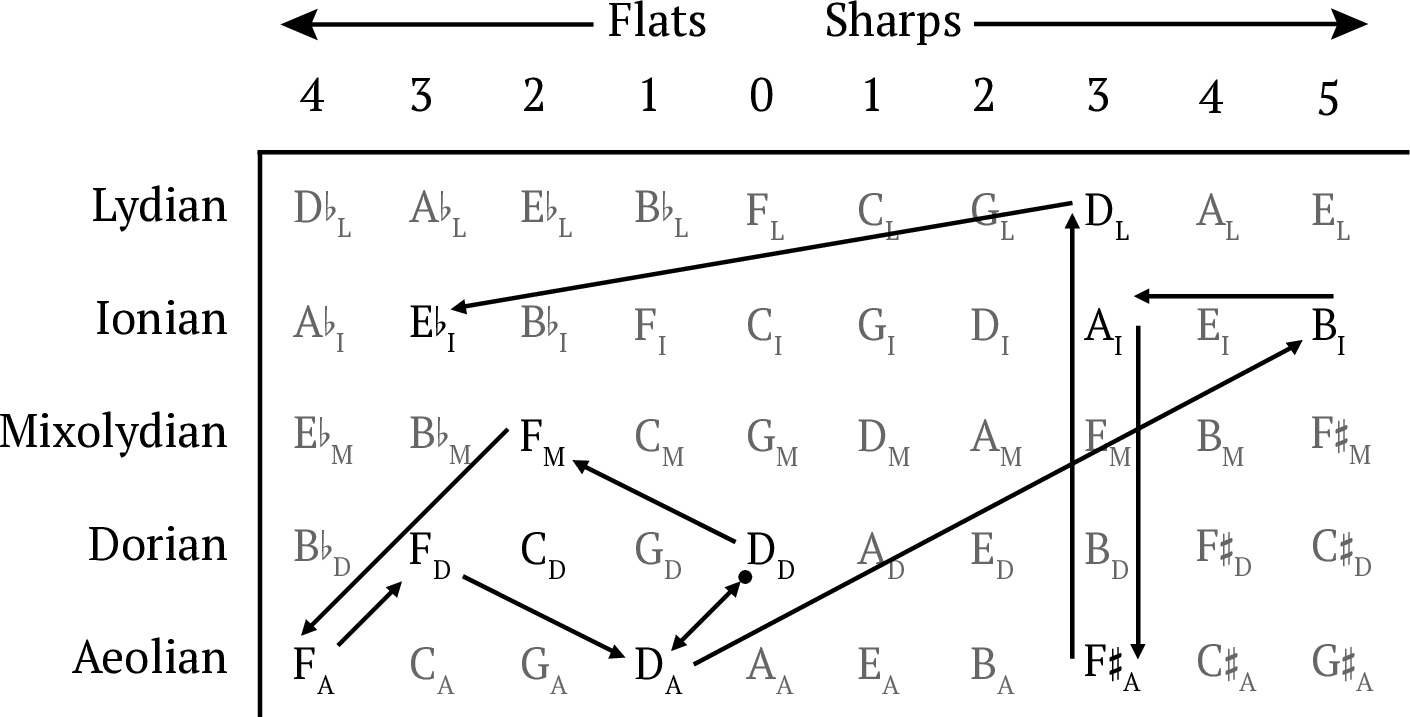

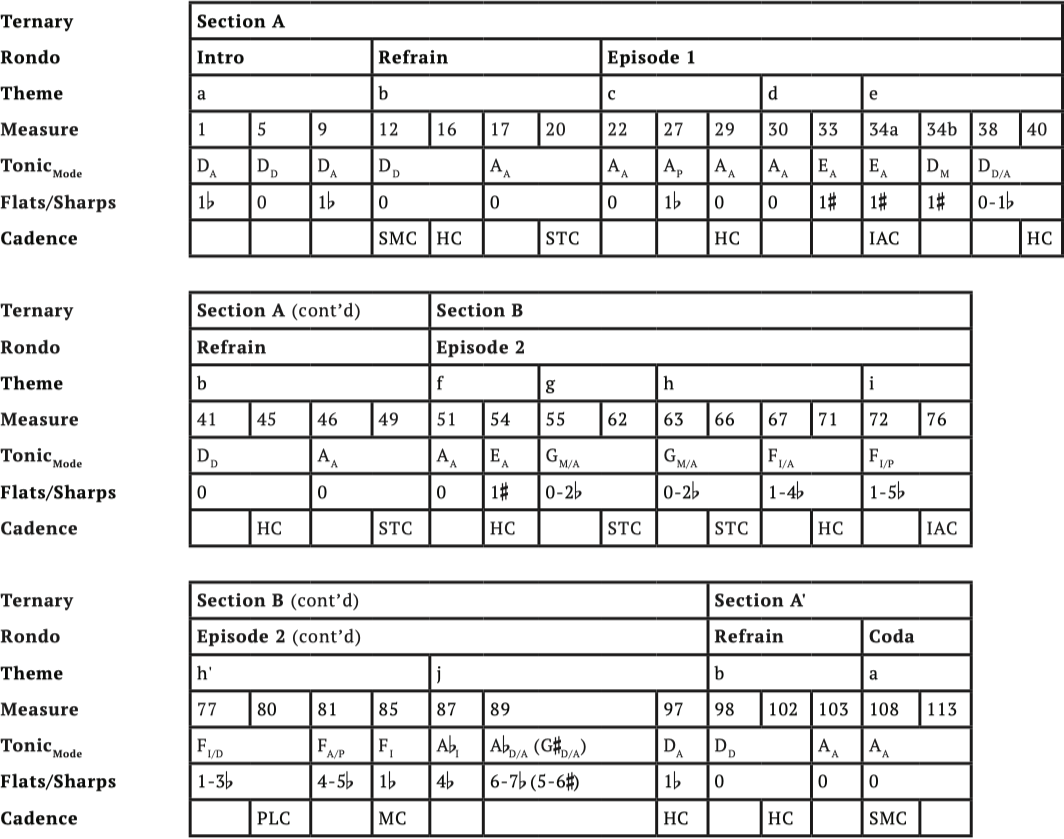

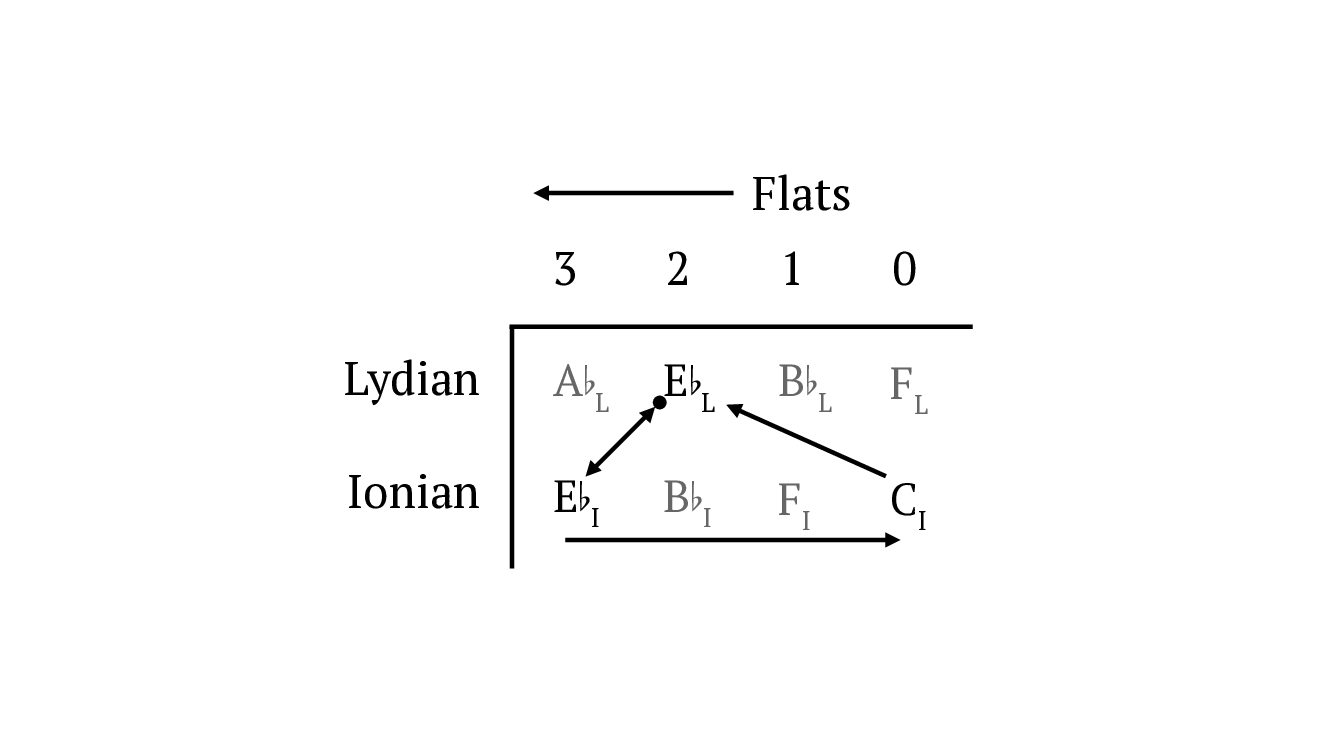

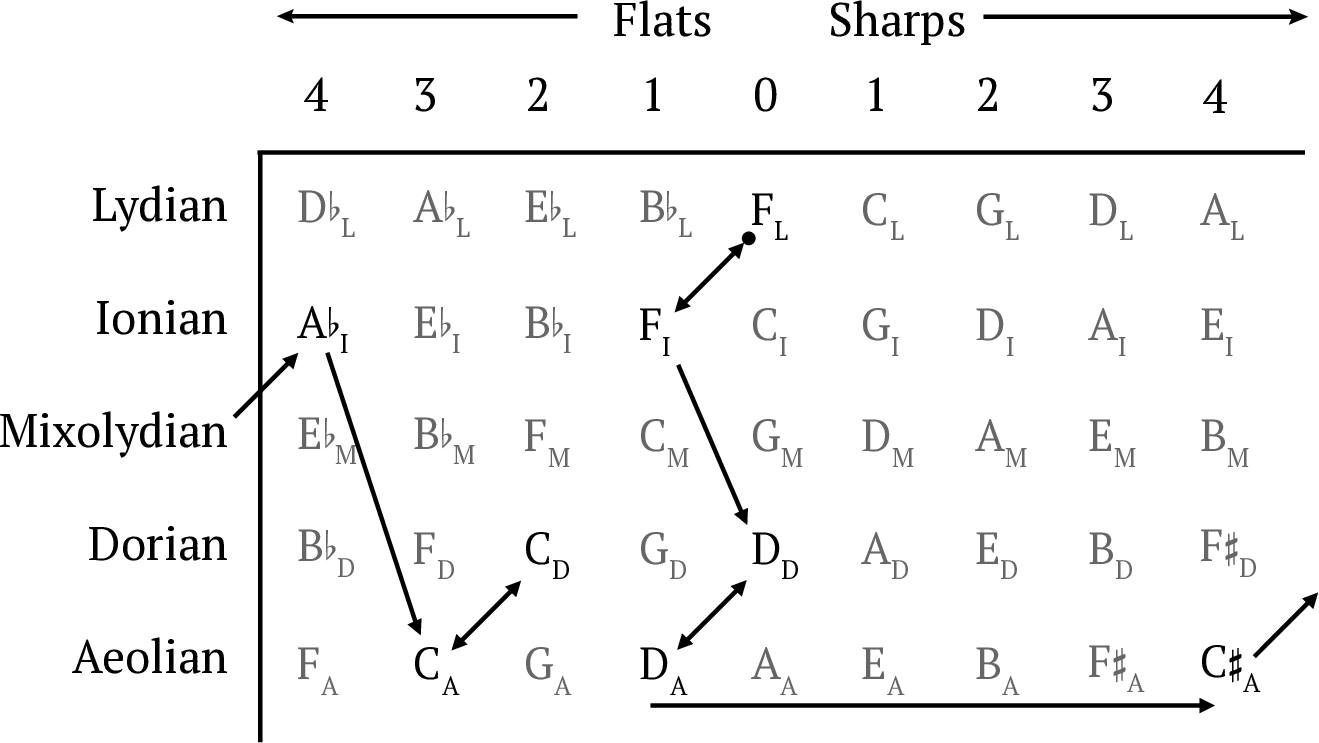

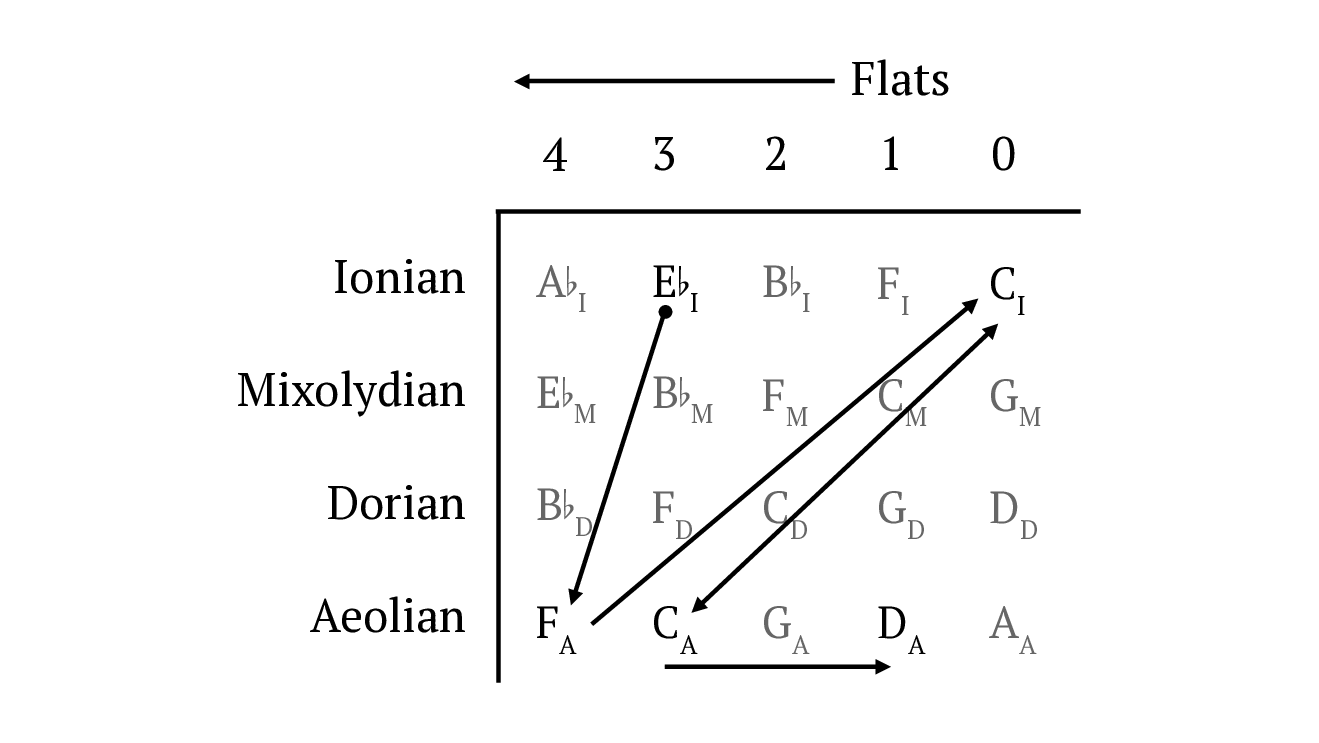

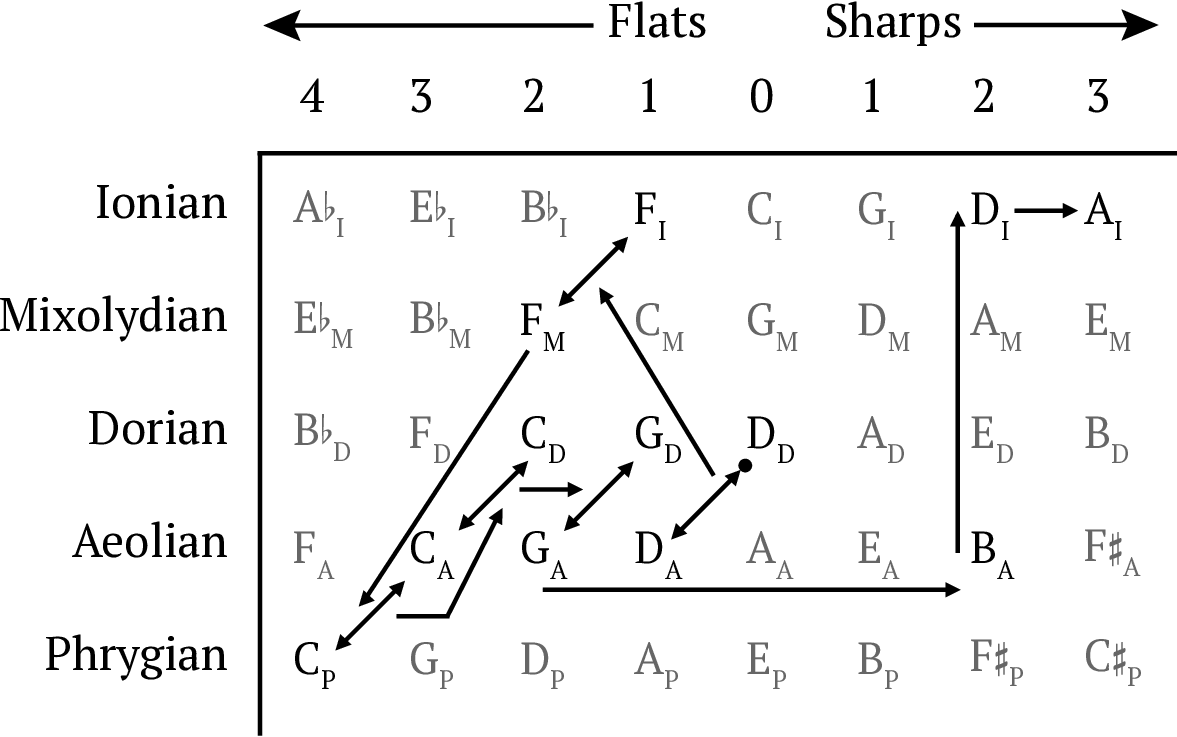

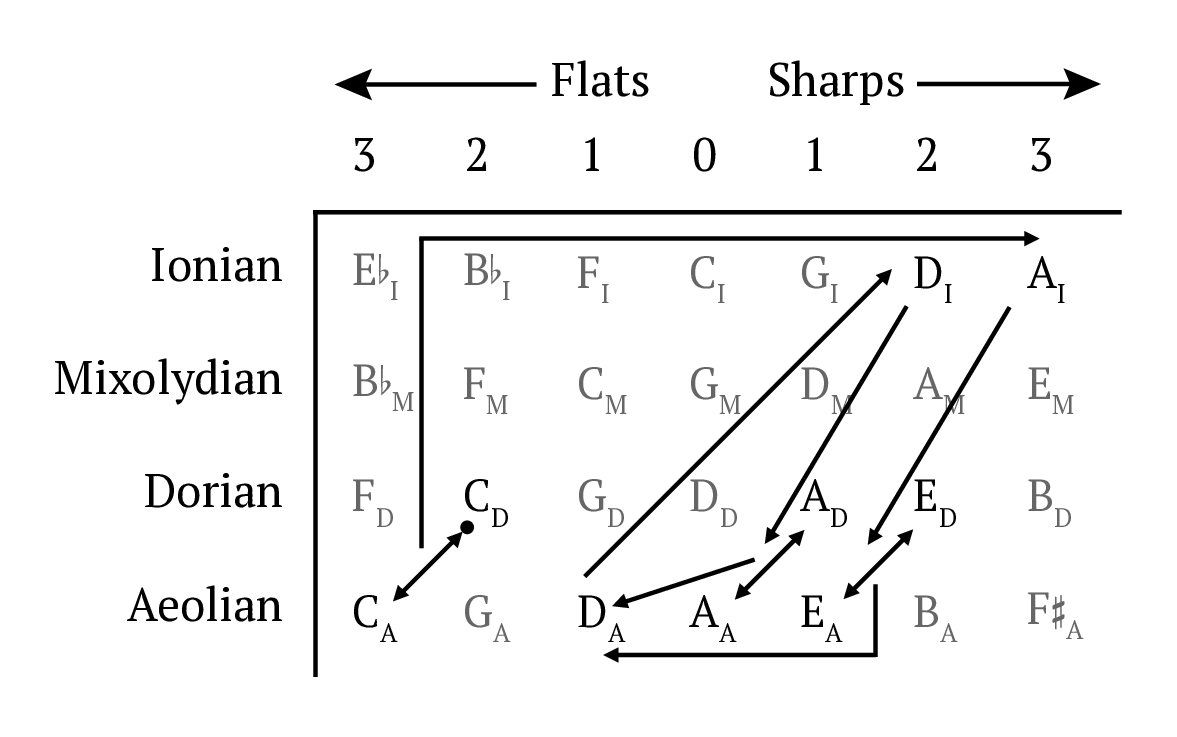

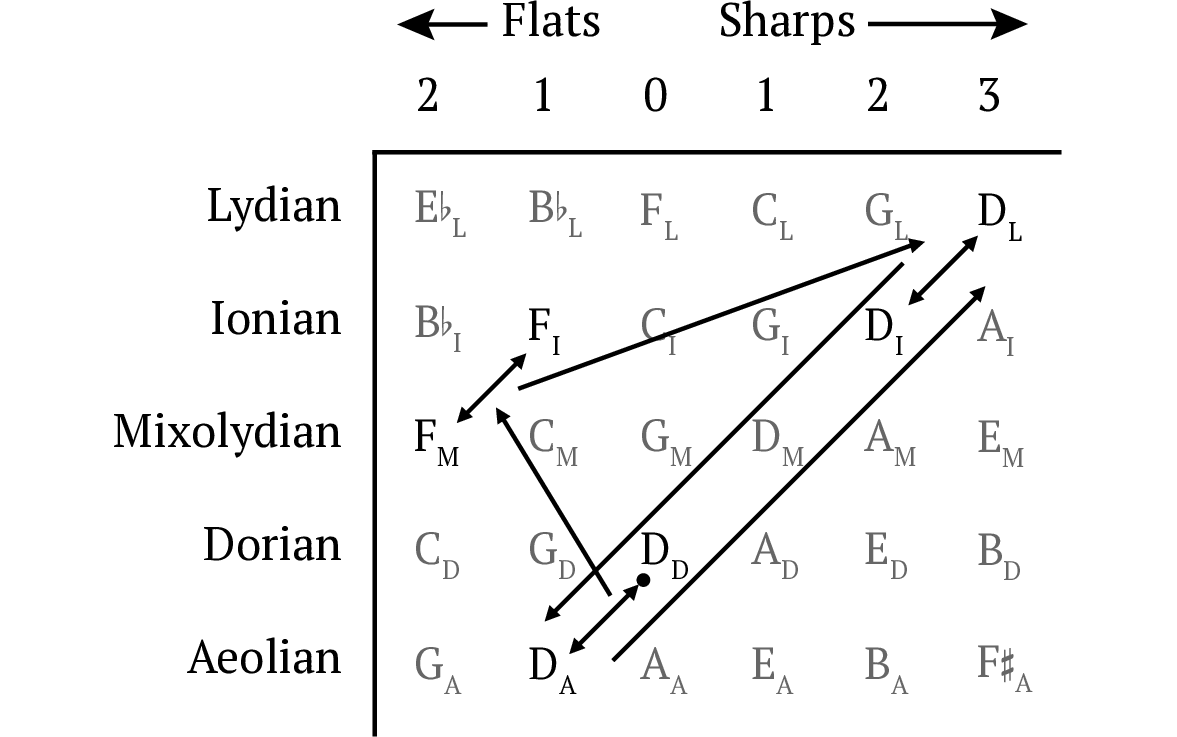

Given Ewazen’s “folkish, Vaughan-Williams-like use of modes,” Page (1986, 14), as quoted in McNally (2008, 13). scholarly work on Ralph Vaughan Williams is also relevant. In his analyses of multiple modal works by Vaughan Williams, Ian Bates introduces both definitions and visual representations useful for approaching music that entails frequent tonal shifts involving more than one mode. As he notes, tonality entails “three diatonic domains: key signature, scale type, and tonic . . . . [A]ny diatonic relationships within a work always require variation in at least two of the three domains” (2012, 35). Example 3 shows his Table of Diatonic Relations, which elegantly represents relations between the three domains. Members of a column share a key signature, members of a row share a mode, and members of a rising diagonal line share a tonic pitch. The shaded regions show all “diatonic tonalities related by fixed domain to D~D~” (D Dorian). Bates (2012, Examples 9–10, 39). Subsequent charts in this article adopt Bates’s practice of indicating a tonality based on a capital letter representing tonic and a subscript letter indicating mode. This requires using Ionian instead of major and Aeolian rather than minor (regardless of the presence of the leading tone). In subsequent analyses in the article, Bates marks the starting tonality of a passage with a dot, traces “trajectories” using arrows, and shades “trajectory systems.” Diatonic trajectories are “directed relationships between tonalities immediately following one another in a given passage of music” (Bates 2012, 37). A trajectory system arises “[w]hen two or more trajectories are related to one another by fixed domain because they share a particular domain conflict” (Bates 2012, 40). Tracing relationships on such a table proves useful in examining the fluctuations of tonality that pervade much of Ewazen’s music.

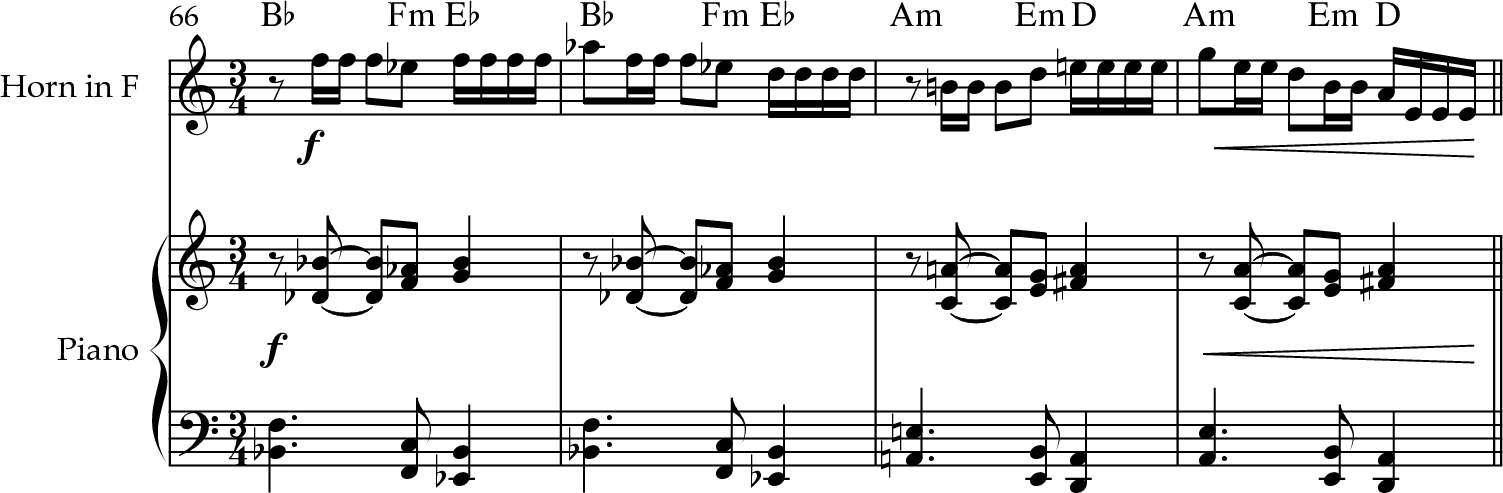

Rock music has also influenced Ewazen’s approach to modes and sonorities. His interest in the genre dates to at least his high school years when he composed a rock musical entitled Apocalypse (McNally 2008, 4). He notes, “the modality of rock music is something that attracted me to it” (Altman 2005, 100). Indeed, rock commonly features both changes of mode between sections as well as modal mixture within a section, as has been well documented by Walter Everett (2004), Nicole Biamonte (2010), Brett Clement (2013, 2019), Brad Osborn (2017), and David Temperley (2018), among others. Ewazen’s music contains numerous similar passages blending or juxtaposing modes. As David Temperley (2018, 43) notes, rock overwhelmingly features root-position chords. Ewazen’s chords likewise tend to be in root position, which clarifies the role of added tones when present and lends a rock quality to some passages. For Ewazen’s account of his early exposure to rock, see Altman (2005, 164–166). For example, the passage from the Sonata for Horn and Piano in Example 4 contains exclusively root-position major and minor triads voiced with parallel fifths in the left hand of the piano.

Ewazen’s sonorities also reflect elements associated with twentieth-century American composers. His preference for wide spacing and textural clarity reflects “the ‘Americana’ sound of composers such as Copland, Barber, Schuman, Bernstein, and Gershwin.” Snedecker (2001, 33) is quoting Ewazen here. For further comments on how Ewazen’s wide voicing recalls that of Aaron Copland, see Pettit (2003, 32) and Brown (2009, 138). For a comparison of the opening trumpet lines of Copland’s Quiet City and Ewazen’s …to cast a shadow again, see Altman (2005, 23). Sonorities are often, but not always, tertian. Chords built from fifths appear with some frequency. For example, Ewazen’s Sonata No. 2 for Flute and Piano opens with quartal/quintal harmony as shown in Example 5. Ewazen’s Sonata for Trumpet and Piano similarly opens with quartal/quintal harmony (McNally 2008, 19). This passage also exemplifies the tonic pedal common in Ewazen’s opening passages, here anchoring C Aeolian. Even chords that are basically tertian frequently feature added tones. As Altman (2005, 135) notes, “added seconds, fourths, and sixths are used in addition to dyads, triads, seventh chords, and other extended chords.”

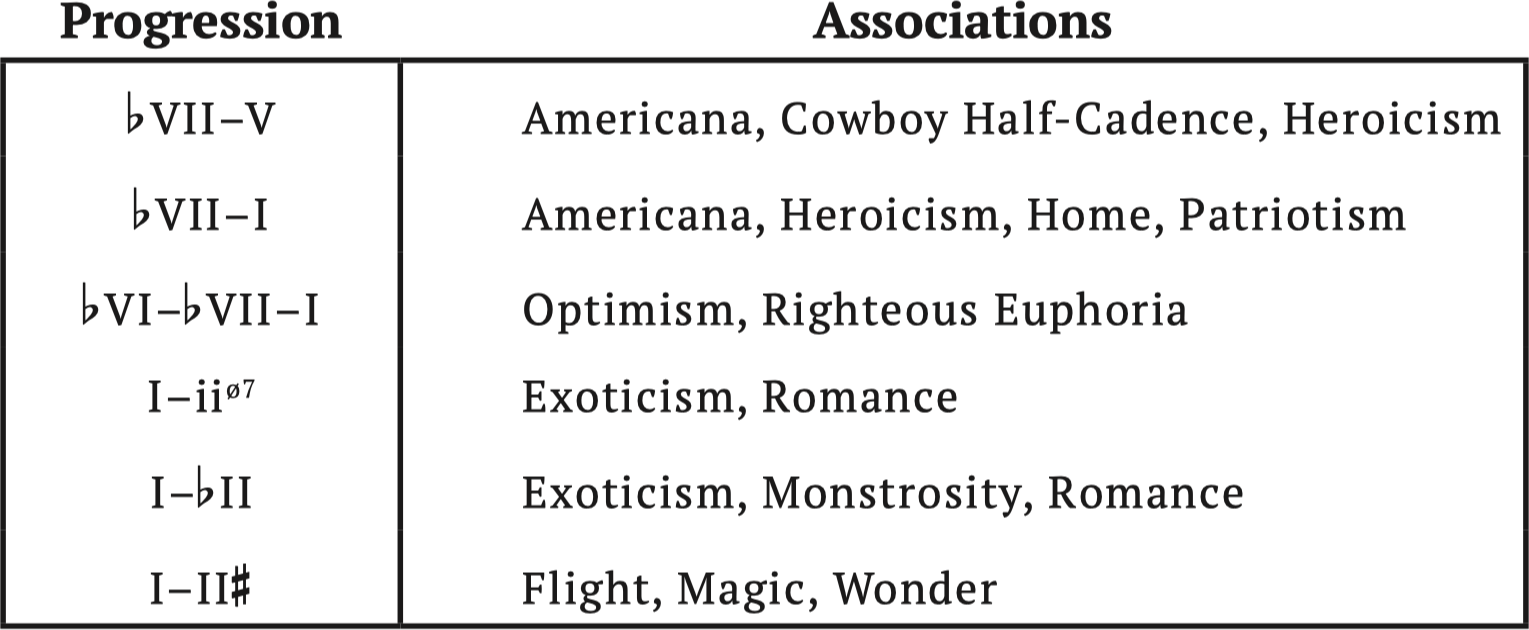

While Ewazen does not cite specific film or video game composers, aspects of Ewazen’s use of modes and cadential structure embrace techniques common in those genres. Indeed, music from film and video games colors associations of specific modes and modal harmonies, some of which influence Ewazen’s music. Focusing on John Williams, Tom Schneller (2015, 51–52) identifies mixture progressions that entail diatonic modes beyond major and minor:

In major keys, Williams frequently replaces diatonic minor and diminished chords with major triads borrowed from the Aeolian, Mixolydian, Lydian, or Phrygian modes . . . . The elimination of minor and diminished triads results in a major key on steroids—a simple but effective procedure in heroic passages of Williams’ film and ceremonial music.

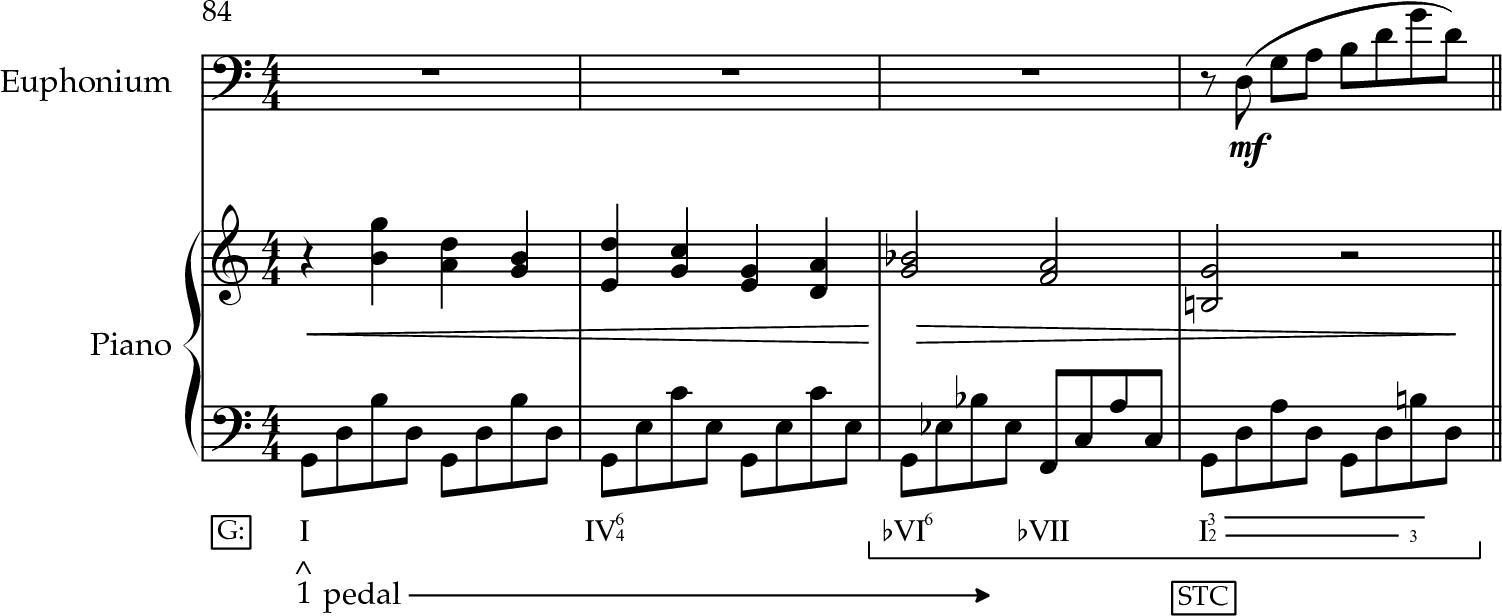

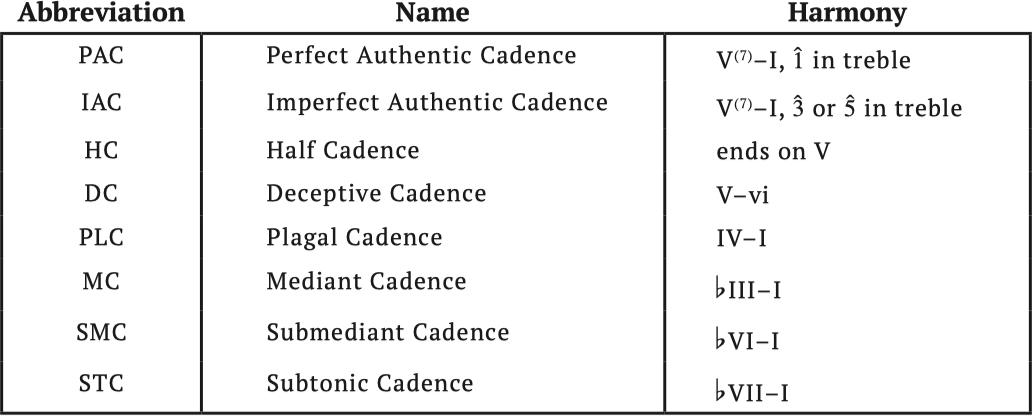

Providing numerous examples from Williams and earlier film composers as well as Aaron Copland, Schneller unpacks the extramusical associations of specific progressions as summarized in Example 6. Ewazen employs saturation of major triads and some of these specific progressions. Example 7 illustrates both with an excerpt from the third movement of Ewazen’s Sonata for Euphonium and Piano: the phrase uses exclusively major triads and ends with one of the progressions from Example 6. Building on Schneller’s work, Sean Atkinson (2019) highlights the association of Lydian mode with the idea of soaring in film and video game music. This sense of exuberant flight inhabits Ewazen’s Lydian passages as well, including the opening of the first movement of Sonata No. 1 for Flute and Piano discussed in Part II. Frank Lehman notes that the expanded harmonic palate of film music requires an expansion of allowable cadence types. While differing in detail, Example 8 loosely adapts Lehman’s chart (2018, xiv) to catalogue conventional and unconventional cadences appearing in the analysis of Ewazen’s music below. Lehman’s list (2018, xiv) includes categories such as modal cadence, chromatic cadence, and chromatically modulating cadence.

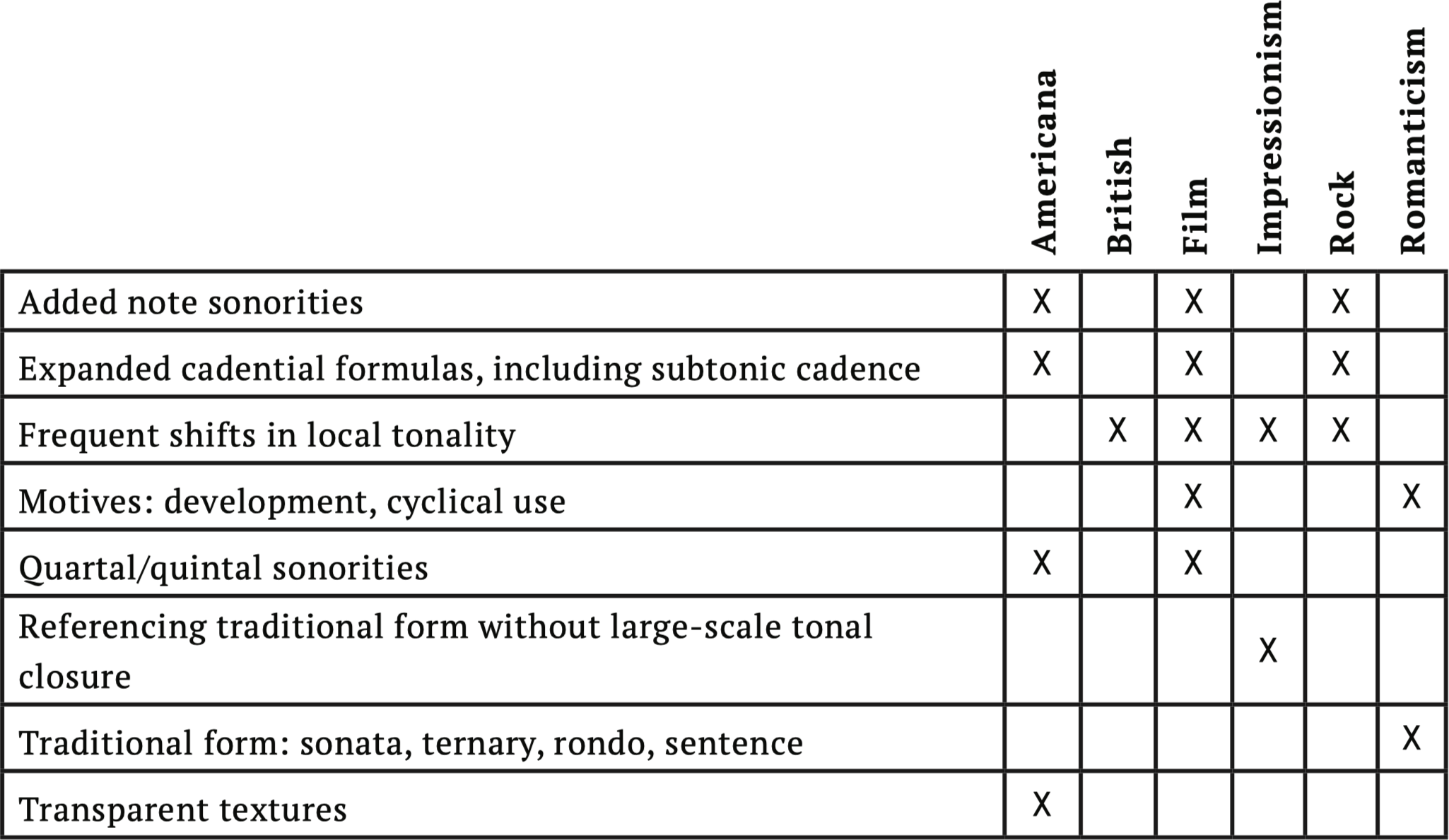

As this section has shown, Ewazen’s music draws on aspects of classicism, romanticism, impressionism, folk song, Americana, rock, and even film. Consequently, analyzing his music requires a similarly eclectic array of analytic tools. Terminology from Caplin and Sonata Theory proves useful when examining some aspects of form. Bates’ Table of Diatonic Relations aids in tracking Ewazen’s frequent tonal shifts that traverse some combination of tonal centers, modes, and collections. Analyzing phrase structure requires considering an expanded list of cadence types drawn from idioms common in film, among other genres. Each of these tools plays a role in the analysis of Ewazen’s Sonata No. 1 for Flute and Piano in Part II.

Before delving into the analytical details of that work, it might also be worth asking why today’s composers continue to write sonatas. Plausible answers range from the pragmatic to the artistic. One reason may simply be the nature of commissions, as some performers and organizations are still interested in new sonatas featuring a particular instrument. Indeed, the vast majority of Ewazen’s sonatas were written for a specific person. For descriptions of his collaborative process, see Brown (2009, 141–142). Another reason might be the influence of training, as the typical music curriculum (including that of Eastman and Juilliard, the schools Ewazen attended) includes extensive consideration of formal processes and specific examples of sonata cycle works. McNally (2008, 7) provides an example from Ewazen’s composition lessons: “While teaching in a contemporary style, Adler would use analysis of traditional scores of Haydn and others to demonstrate compositional structure.” Remaking traditional forms in an updated musical language combines the convenience of models with the weight of connecting to an extended historical tradition. Some motivation might be due to the attractive musical resources built into the sonata cycle itself, which balances unity and contrast both within and between movements. Each of these appears to motivate aspects of Ewazen’s Sonata No. 1 for Flute and Piano, as the analysis of individual movements below illustrates.

Part II: Analysis of Sonata No. 1 for Flute and Piano

Movement I: Allegro leggiero

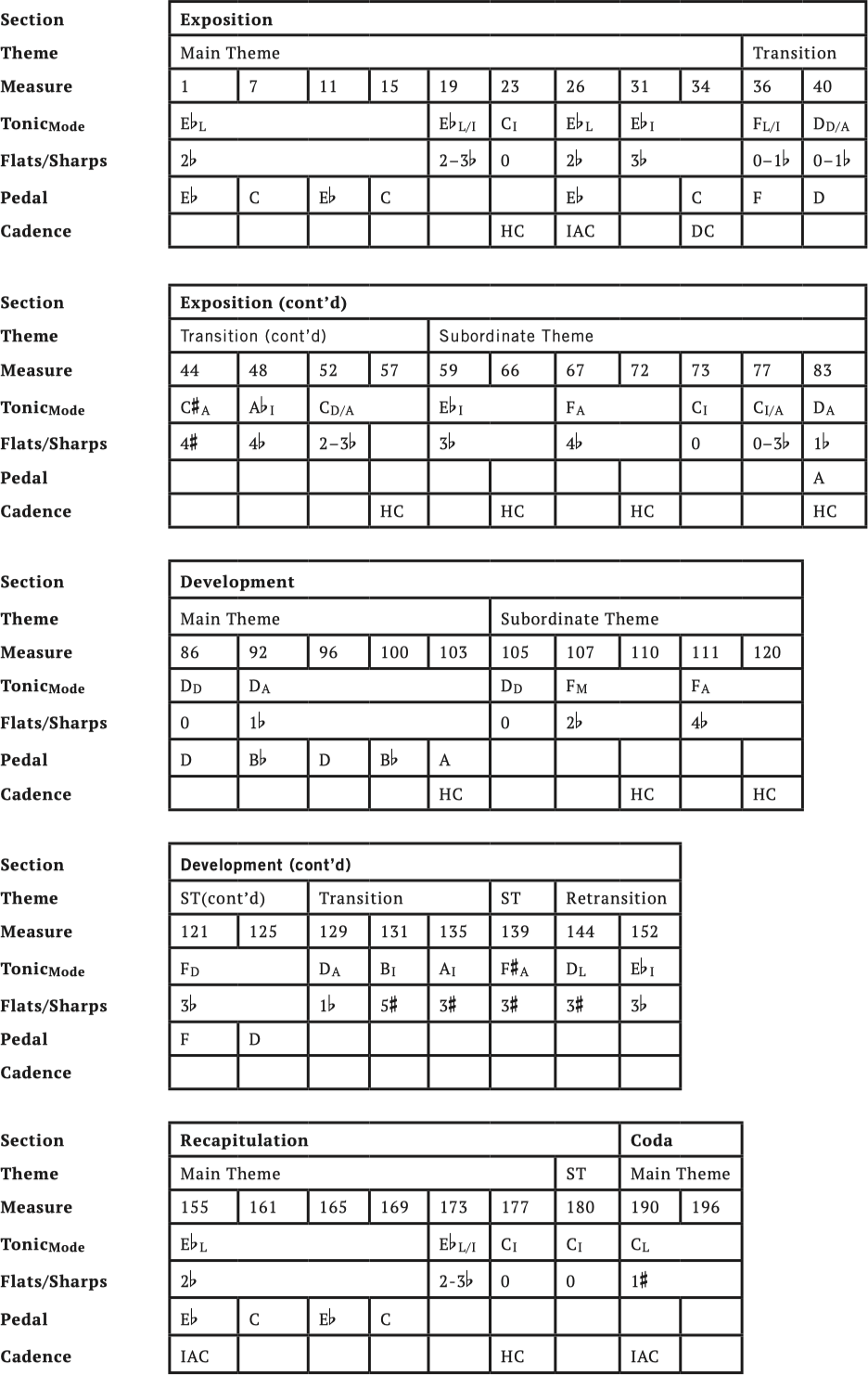

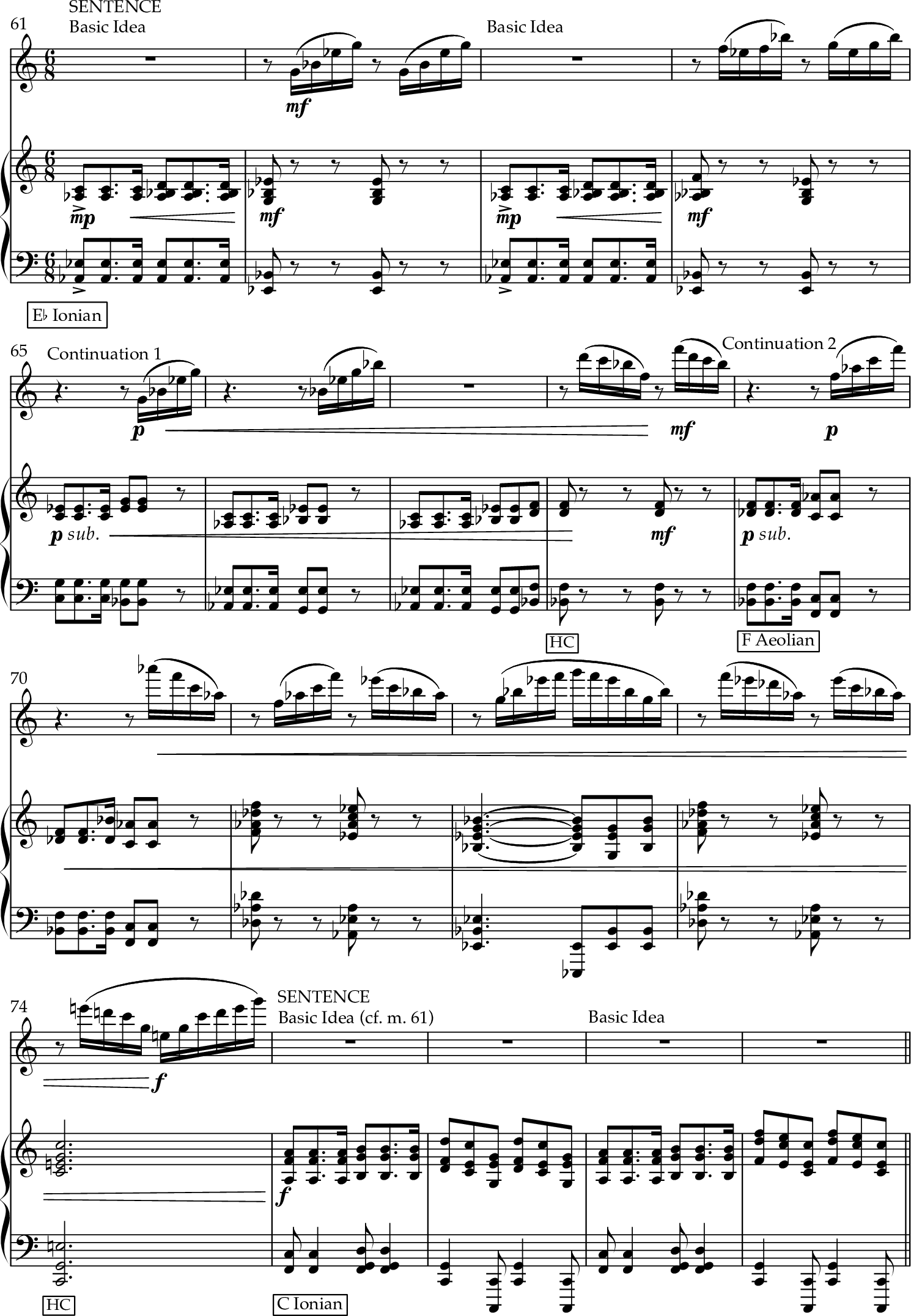

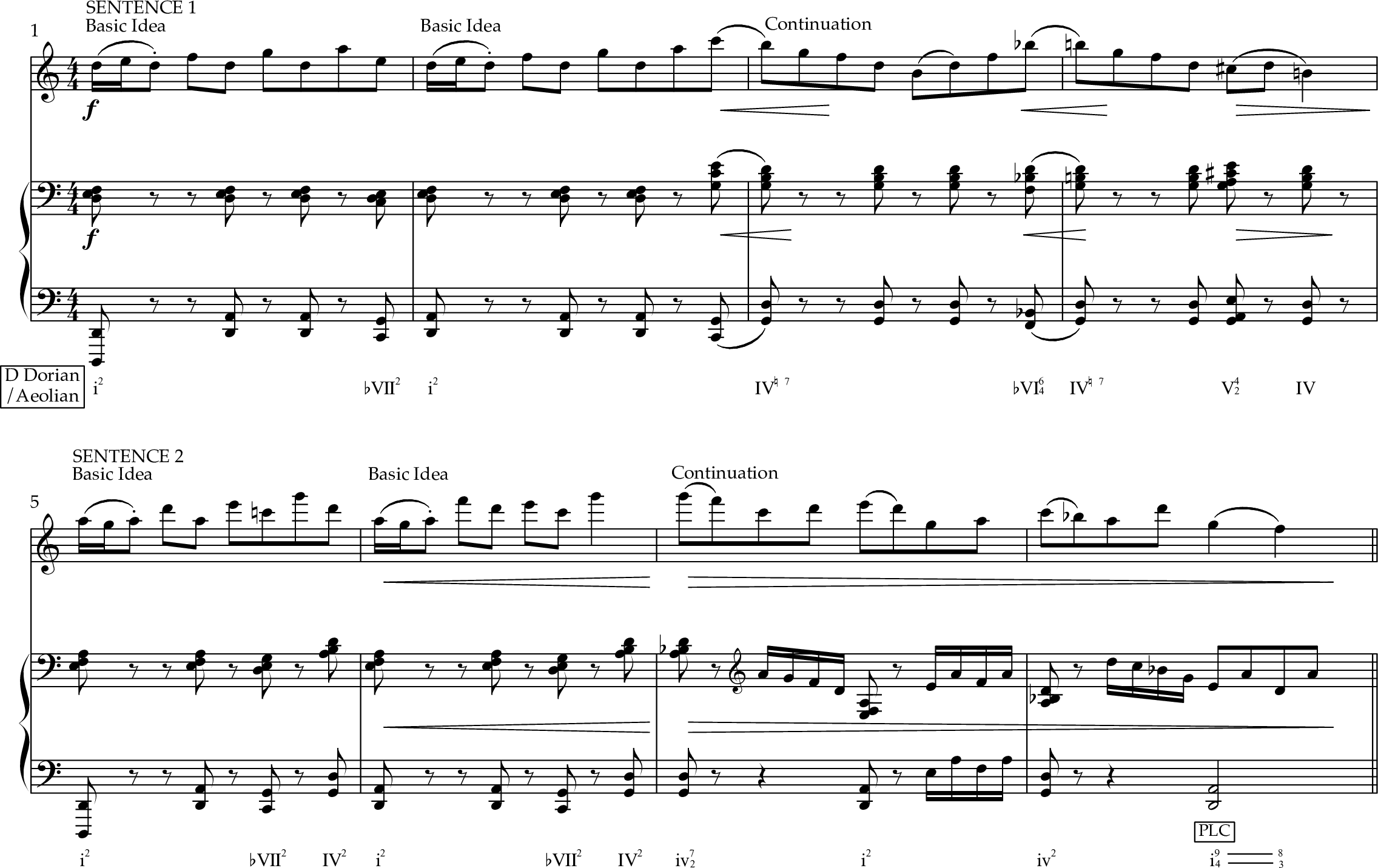

In the sonata-form first movement, modes and motives surpass conventional means of providing coherence and closure. Themes, instrumentation, and degrees of stability anchor the abundant shifts in tonality. Example 9 provides a form diagram of the movement. Conventional cadences are infrequent and relatively weak, including mainly half and imperfect authentic types. Thematic return articulates major boundaries in the form, as the main theme marks the beginning of the exposition, development, recapitulation, and coda. The exposition introduces three themes, all of which resurface in the development. In contrast, the brief recapitulation excises the entire transition and parts of the subordinate theme for a focused path toward the coda.

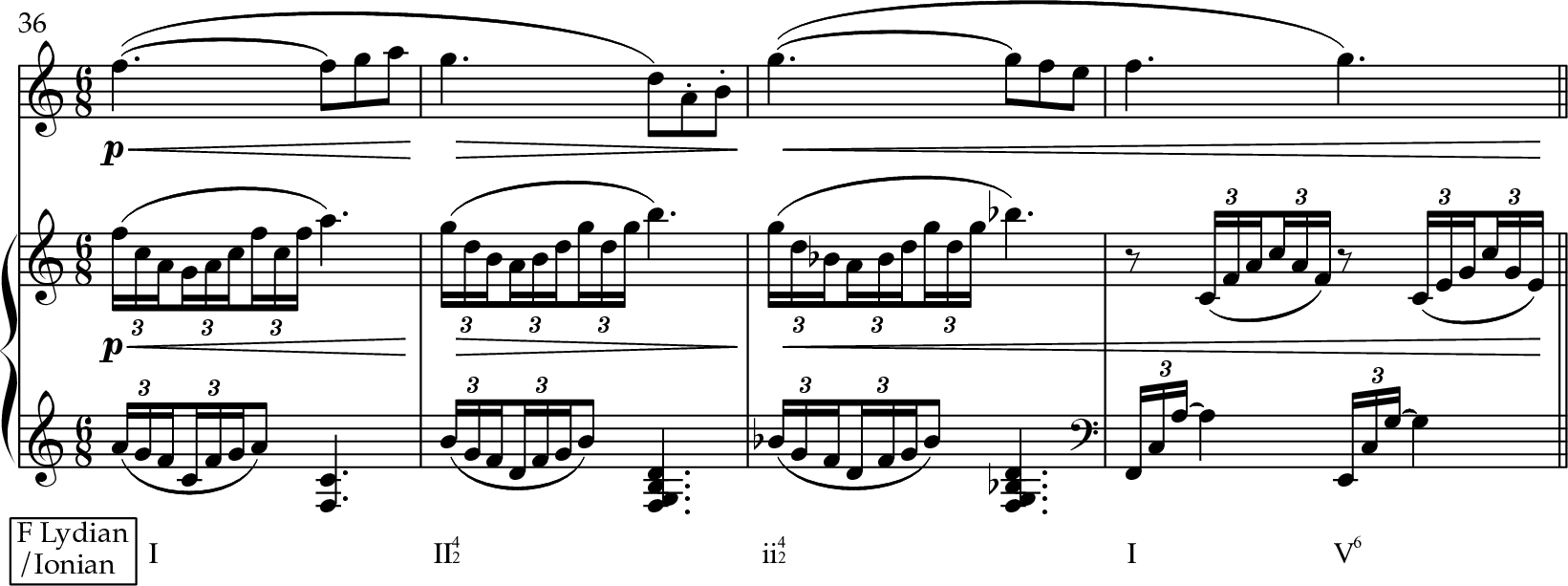

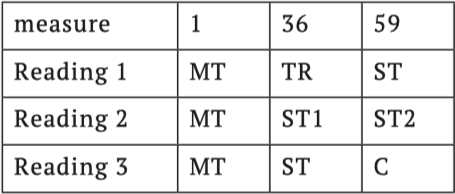

The three portions of the exposition allow for three viable interpretations in function. Instrumentation and texture assist in articulating the beginning of each segment. The flute leads in the first (Example 10) and second (Example 11) portions, whereas the piano emerges as the leading voice at the start of the third (Example 12). All three sections feature different patterns in the piano part. Example 13 compares three possible interpretations of these sections. The question is whether there is a transition, a closing theme, or neither. Following Caplin, the first two readings in Example 13 are plausible, but the third is unlikely given the nature of the third segment (given the restriction of C to codetta rhetoric). From a Sonata Theory perspective, the first or the third readings are possible, though cadence types pose problems to the third. Measure 34 could be read as a medial caesura (MC) given the drop in energy immediately following the cadence, but the deceptive cadence here would be an odd choice to articulate this boundary (Example 9). The boundary between the second and third segments functions even less convincingly as an EEC given the lack of PAC and the change of key at the start of the third section. Tonal stability in the exposition and thematic return in the recapitulation support the first reading in Example 13, which corresponds to the more detailed reading in Example 9.

The tonal stability of the three themes aligns with typical expectations for tight-knit and loose passages, as demonstrated in Example 14. These examples adopt the nomenclature and presentation of Bates 2012. The main theme (Example 14a) is by far the most stable, exploring only three tonalities, two sharing E♭ as tonic and two sharing the Ionian mode. All three are present both in the first pass through the theme starting in m. 1 and the compressed repeat starting in m. 26. The transition (Example 14b) is far more mercurial, weaving between distant tonalities roughly every four measures. This passage loosens all three aspects of tonal relations with four modes, five tonics, and five collections ranging from four flats to four sharps. The subordinate theme (Example 14c) lies between these extremes, looser than the main theme and tighter than the transition. Figure 1.5 of Caplin (2009, 38) contains a useful chart summarizing the tight-knit versus loose continuum. For more detailed discussion, see Chapter 8 (“Subordinate Theme”) and Chapter 9 (“Transition”) of Caplin (1998). While the subordinate theme contains internal repetition like the main theme, it places the second pass at m. 73 in a different tonality. Rather than breaking from the tonalities of the main theme as would be typical for older sonatas, this subordinate theme highlights two of the three tonalities from the main theme. They even appear in the same order, featuring E♭ Ionian at the subordinate theme’s opening in m. 59 and C Ionian at the repetition in m. 73.

Main theme (tightest).

Transition (loosest).

Subordinate theme.

Tonal trajectories in the exposition, Ewazen, Sonata No. 1 for Flute and Piano/I.

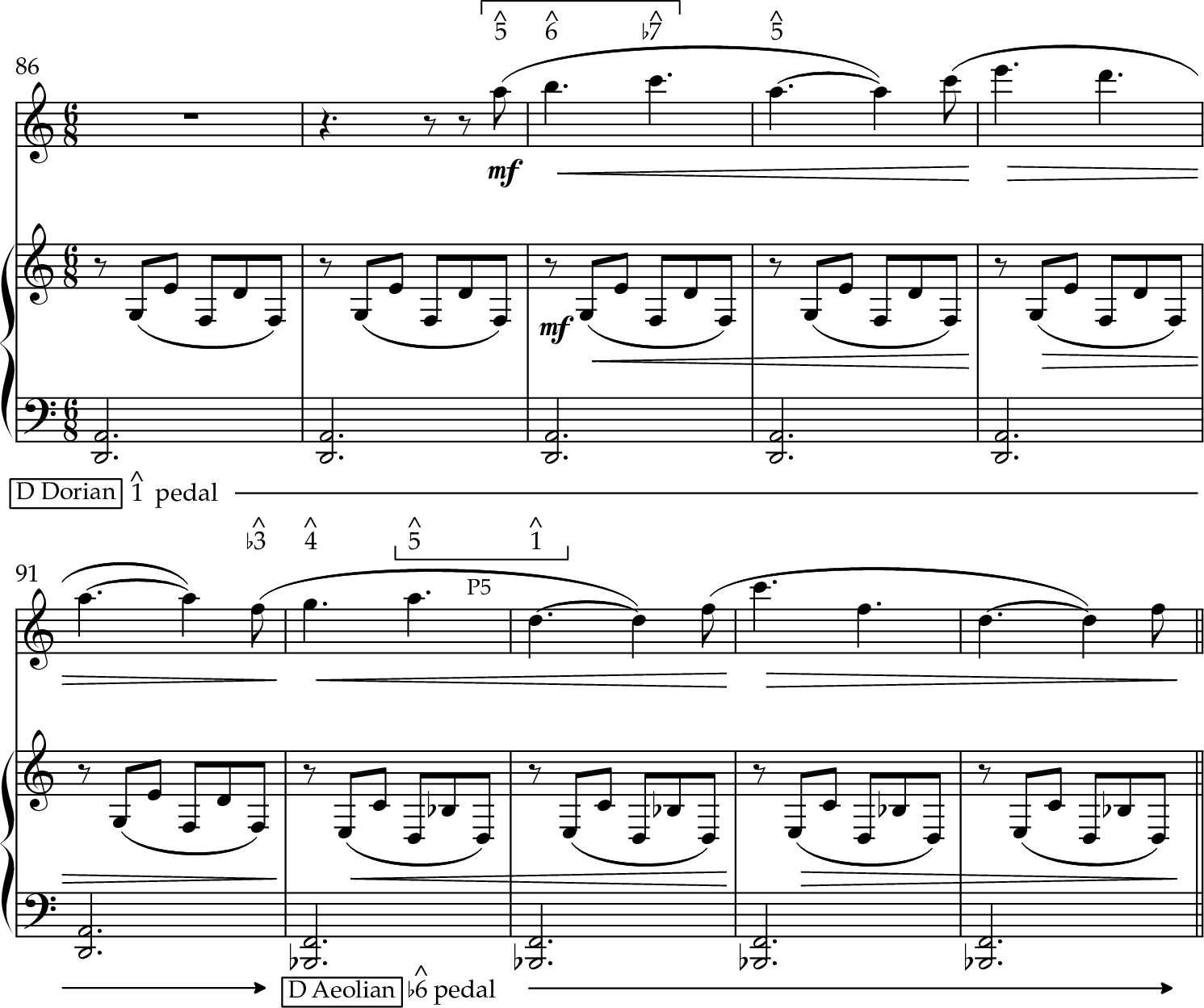

The development, as expected, considerably loosens materials from the exposition. All three thematic zones return, though not in a strict rotation: most of the material derived from the subordinate theme enters before material drawn from the transition. The first movement of Ewazen’s Sonata for Trumpet and Piano similarly develops all themes from the exposition (McNally 2008, 30). In contrast to the major modes emphasized at the start of the exposition, the first two-thirds of the development emphasizes minor modes. Example 15 shows the tonal trajectories of the development, highlighting the presence of five modes, five pitch centers, and seven different collections. Each individual tonality, however, relates to at least two others through shared tonic, mode, or implied key signature, thus balancing variety and cohesion.

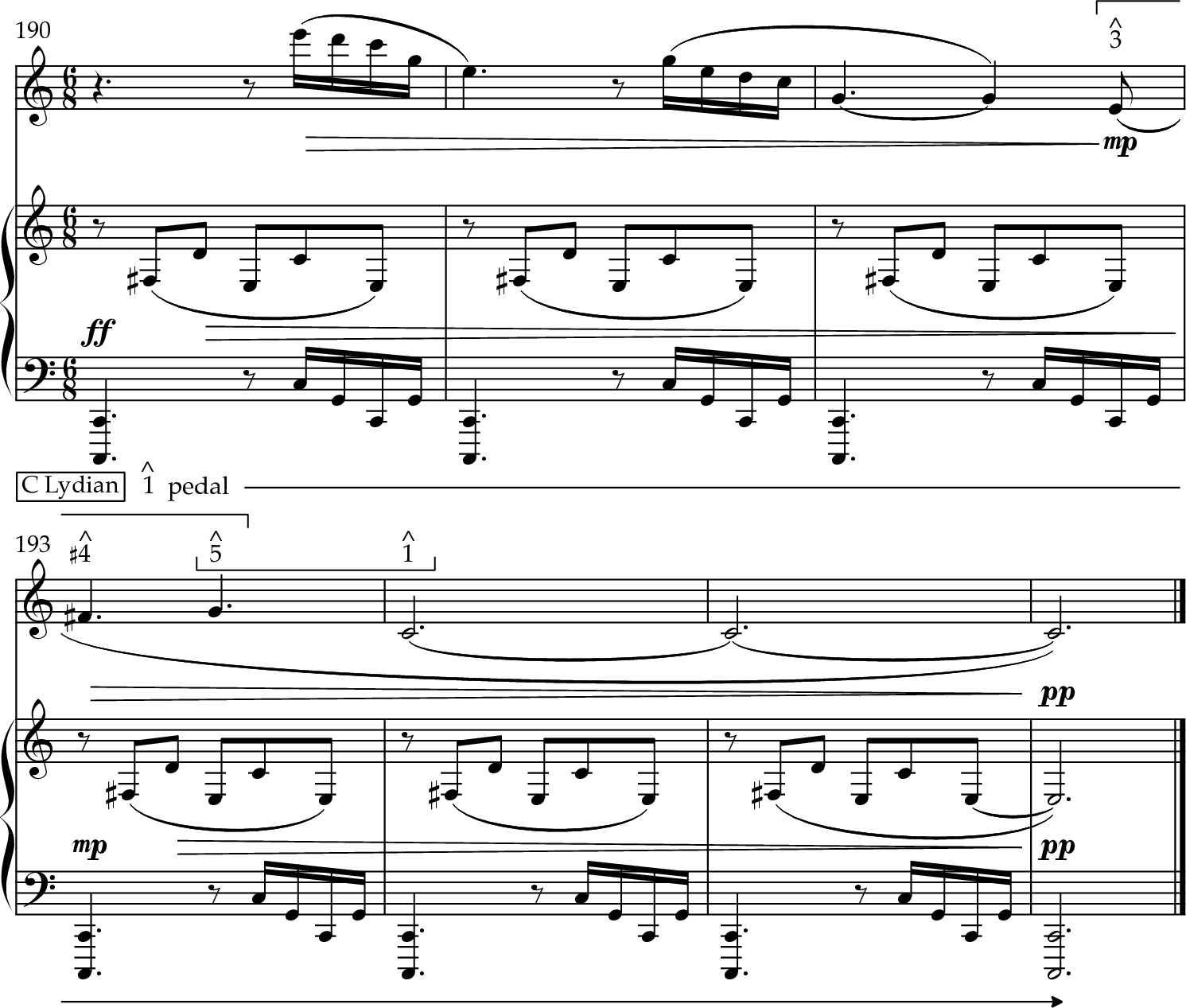

When considering the movement as whole, the main and subordinate themes articulate and ultimately resolve the central conflict, which revolves around the pitches E♭ and C. The soaring main theme opens the work in E♭ Lydian, with later passages shading into Ionian (Example 10). The bass line alternates pedal tones on E♭ with those on C without seriously challenging E♭ as the clear tonal center. In contrast, Example 12 shows how the subordinate theme in the exposition intensifies the competition between these two pitches through scalar shifts. The passage opens in E♭ Ionian with a sentence that arrives on a half cadence in m. 68. The second, longer continuation in F Aeolian ends with a half cadence on a C major triad in m. 74. Measure 75 marks the climax of the theme with a forte restatement of the basic idea in C Ionian. The subordinate theme thus reaffirms the importance of E♭, elevates the role of C, and balances the main theme’s Lydian pull with longer stretches in major. The drastic shortening of the recapitulation focuses the tonal narrative of the movement. As noted in Example 9, the slightly abbreviated main theme is reworked to conclude in C Ionian. The compressed subordinate theme remains in C Ionian throughout. The coda further affirms C through one final modal shift, concluding in C Lydian.

The satisfying nature of this coda stems partially from transformations of the main theme that span the entire movement. As introduced earlier, Example 10 compares three significant iterations. The piano ostinato is similar throughout, diatonically transposed for the development, and transposed and embellished with sixteenths for the coda. Changes in the flute are more subtle. Scale degree annotations above the flute part highlight recurrences of a four-note motive (two ascending steps and a downward leap). The exposition and development transpose at least the first part of the motive down by two diatonic steps but involve different starting scale degrees: to in the exposition and to ♭3 in the development. The second iteration in the development widens the last interval to a fifth rather than the expected third, as the upward bracket indicates. Downward brackets highlight the ascending major second followed by minor second melodic opening to all three sections, regardless of scale degrees. Significantly, the final statement of this motive in the coda combines this major-second/minor-second ascent from the exposition with the descending perfect fifth from to of the development. The flute adds its tonic pedal to that of the piano, reaching the final stage of closure. This motivic synthesis thus brings the piece to rest in C Lydian, combining the opening mode type with the pitch of the second pedal tone. Example 16 highlights how the loop from the exposition’s main theme is transformed into the directed motion from two modes on E♭ to the same two modes on C in the recapitulation and coda. The first movement of the Sonata for Trumpet and Piano provide a different strategy towards recapitulatory design by combining the tonality and harmonies from the main theme with the rhythmic motive from the subordinate theme (McNally 2008, 33).

All in all, this movement jettisons older conventions of sonata form while crafting a compelling narrative reliant on pitch, modes, and motives. Rather than introducing a new and crisp tonal contrast as in a conventional exposition, the subordinate theme exaggerates and transforms qualities already present in the main theme. Delicate shifts in mode serve to color and shape transpositions of motives. The recapitulation neither revisits most previous thematic material nor concludes in the opening key, defying the traditional sonata principle. Ewazen avoids tonal closure without connoting the negative valance of what Sonata Theory describes as “failed” recapitulations (Hepokosi and Darcy 2006, 242–249). The movement starts and ends in different tonalities, but the specific choice of ending tonal center and mode nevertheless contributes to unity.

Movement II: Andante teneramente

The gorgeous slow movement exemplifies composing out in a modal context. Much of the second movement derives from its opening motive, an ascending fifth followed by a descending fourth. The innocuous gesture immediately develops into the opening phrase. This influences the melody and added-note harmony of subsequent sections, including the only theme stated thrice in the movement. The pitches of the opening motive even inform the large-scale tonal organization, determining the specific pitch centers of the outer sections. The perfect fifth infiltrates motive, harmony, and mode with only modest evocation of functional norms.

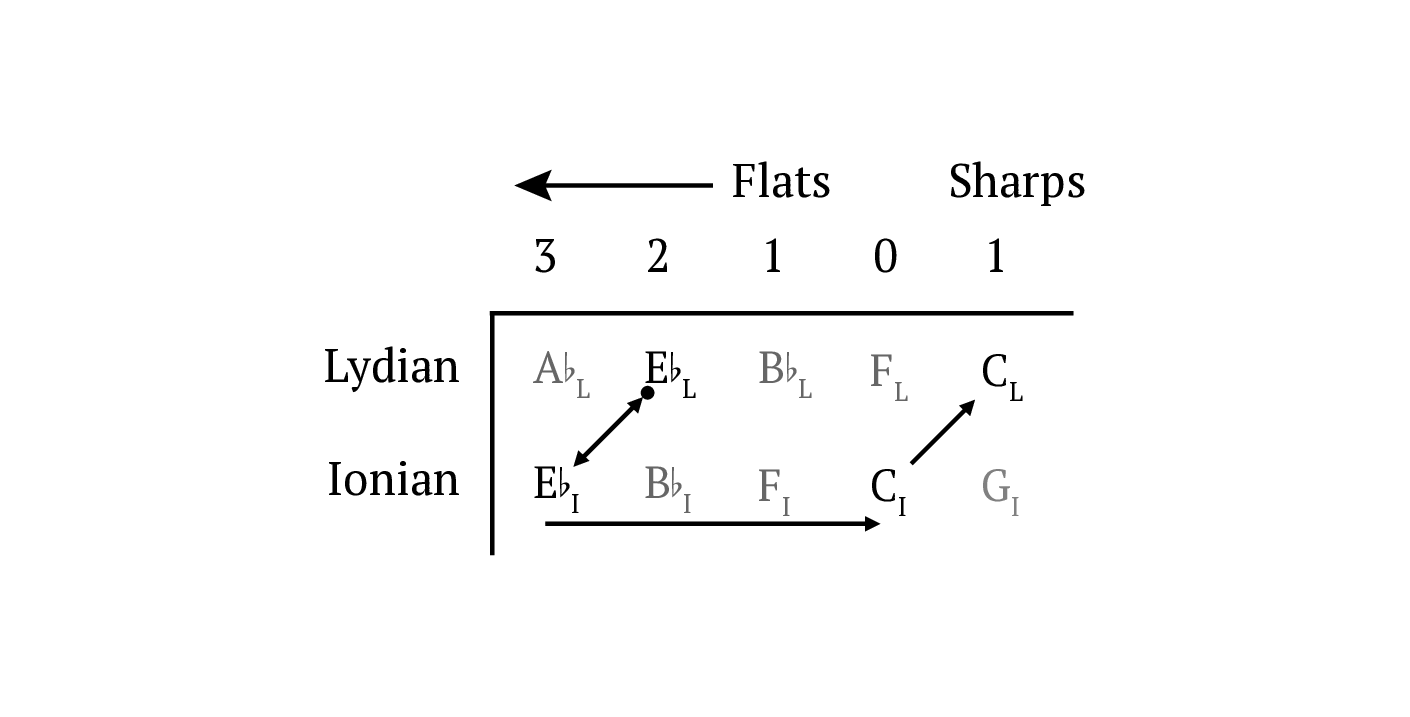

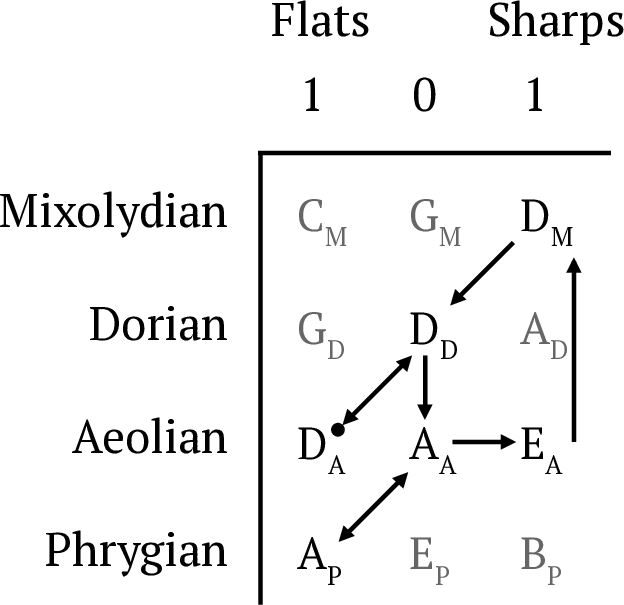

Example 17 shows how the hauntingly beautiful theme a is largely generated from the pitches and contour of the first three notes: D–A–E. Solid boxes mark the original and transposed version of the motive, which involves set class (027) presented with the contour <021>. The notations follow common practice: parentheses indicate set classes, angle brackets mark contour segments, and square brackets mark interval vectors. For lists of relevant sources, see Straus (2016, 93–94 and 157). Some modified restatements preserve set class while changing contour. Sideways brackets show how the bass line of mm. 5–9 uses contour <012>, overtly stacking perfect fifths. Measures 7 and 9 preserve the pitch classes of the original, while the other iterations involve transposition. Other instances of the motive preserve contour but not set class: these include E–A–F, member of set class (015), marked with dotted boxes and B–F–C, member of set class (016), marked with upward brackets. Significantly, the pitches of the first two statements of the motive, D–A–E and E–A–F, combine in m. 12, which concludes the theme with a submediant cadence and establishes one of the piano figurations that recurs frequently throughout the movement.

Example 18 summarizes the relationships between these cells. Comparing the interval vectors highlights how (015) and (016) share ic1, and all four sets contain at least one instance of ic5. The original (027) contains two instances, distilling the quartal/quintal sound to a single trichord. The superset serving as the goal of the introduction basically functions as a minor triad with an added second, reflecting Ewazen’s practice of adding subtle dissonance to basically triadic structures.

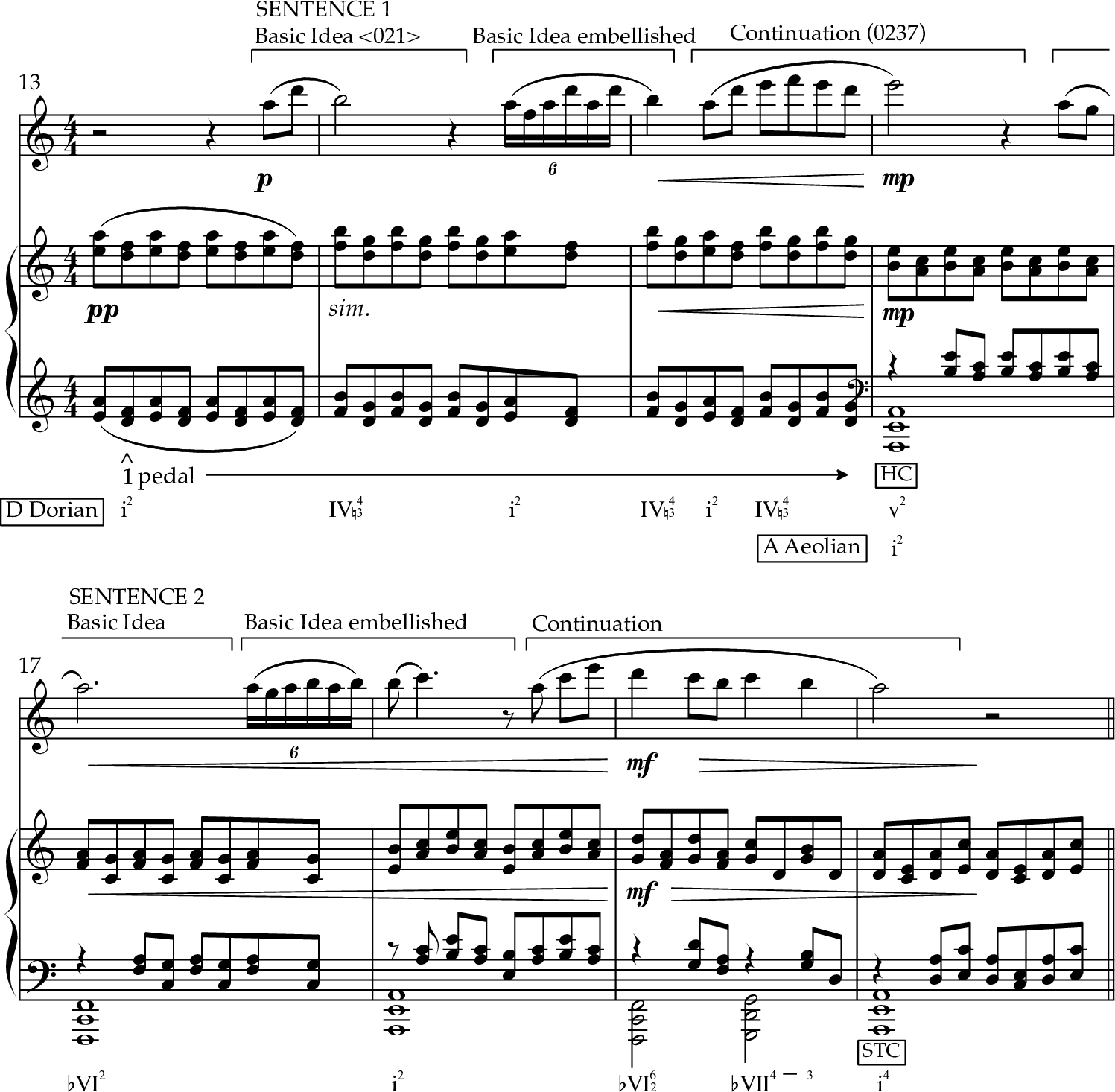

Trading the delicate counterpoint of the opening for homophony, theme b adopts aspects of the opening motive. The passage is fairly tight-knit, containing two four-bar sentences as indicated in Example 19. The loosest aspect involves the shift in tonality from D Dorian to A Aeolian. The first sentence opens with a basic idea featuring the motive’s original <021> contour, with the flute beautifully lingering on the B-natural functioning as the Dorian color tone on the downbeat of m. 14. The continuation melodicizes all four pitches from the end of the introduction: D–E–F–A. The second sentence lacks such specific motivic references but organically follows the same general outline as the first sentence: a minimal basic idea, an embellished basic idea, and a continuation leading to a clear cadence. The harmony throughout the passage frequently features added note chords. These include major and minor triads with an added second and a minor triad with an added fourth. Significantly, each of these harmonies contains (027). The figuration in the piano further emphasizes this saturation of fourths, frequently isolating a fourth or fifth on a given half beat. This passage thus solidifies the significance of the opening motive as well as the general emphasis on fourths and fifths. Theme b returns twice more in the work, serving as a significant anchor in this narrative.

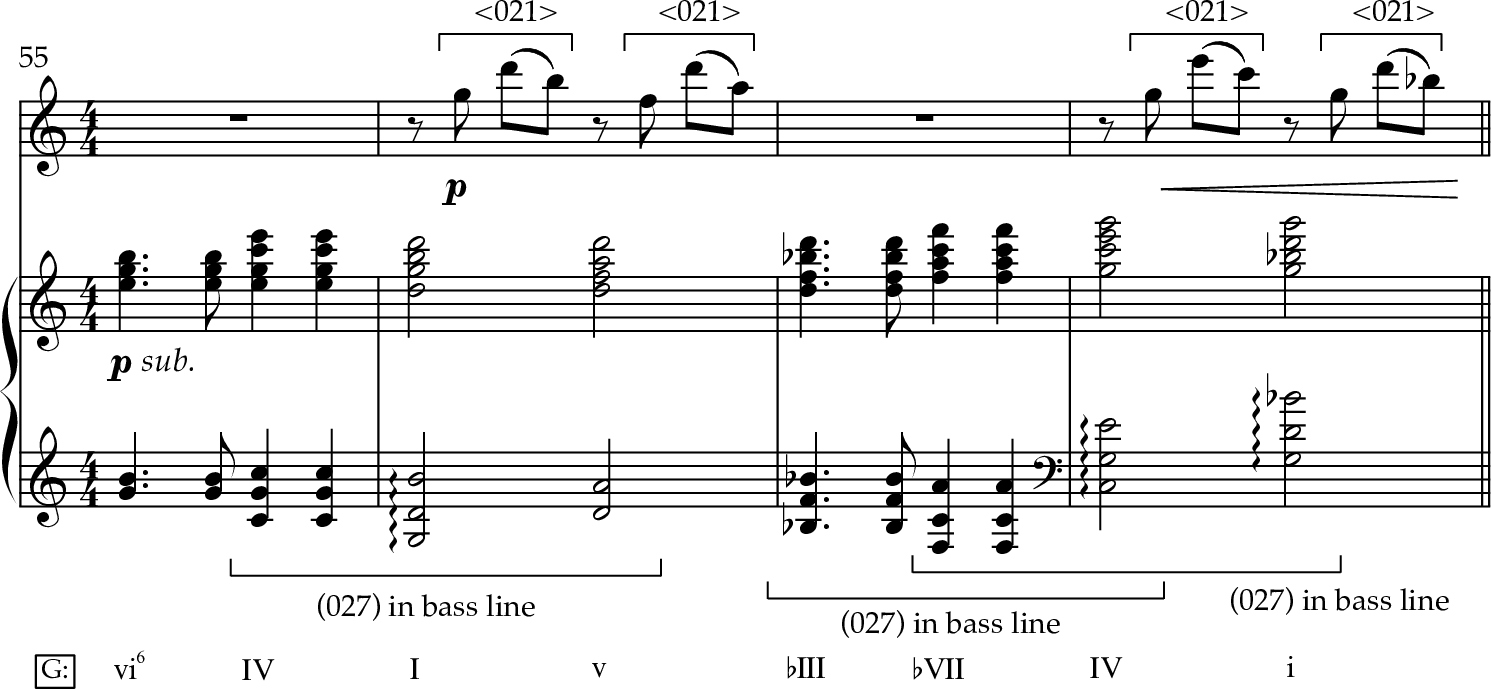

The diagram in Example 20 compares two readings of the large-scale form. Both the ternary and the five-part rondo interpretations involve unusual proportions. In the ternary reading, sections A and B are roughly fifty measures each, while the A′ section is drastically shortened to sixteen measures. The five-part rondo reading likewise seems lopsided, with episode 2 double the length of episode 1 and nearly five times the length of the refrain.

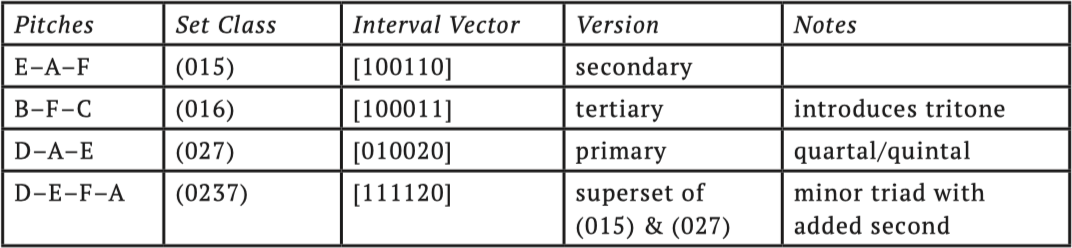

The balance might tip in favor of the ternary reading when considering tonal centers, particularly in relation to the opening motive. As shown in Example 20, the tonal centers of mm. 1–54 unfold two complete cycles through the pitches of the opening motive D–A–E. Most pitch centers mix different flavors of minor modes, briefly brightening to Mixolydian within theme e. Example 21 highlights the proximity of the tonalities; collections only range from one flat to one sharp, and all tonalities are a single direct move away from either D Dorian or A Aeolian (which are a single move from each other). The reversed restatement of theme b and theme a at the end of the movement returns to pitch centers D and A, though not E. Thus, all of the tonalities within sections A and A′ center on one of the pitches from the opening D–A–E motive. Section B touches on these centers at the beginning and end. Furthermore, theme h and theme i are largely built on F, the note added by the first variation of the opening motive: E–A–F. Section B features pervasive, rapid mixture entailing more flats, with fleeting implications of F Phrygian (5 flats) and a more extended passage in A-flat Dorian and Aeolian (6–7 flats).

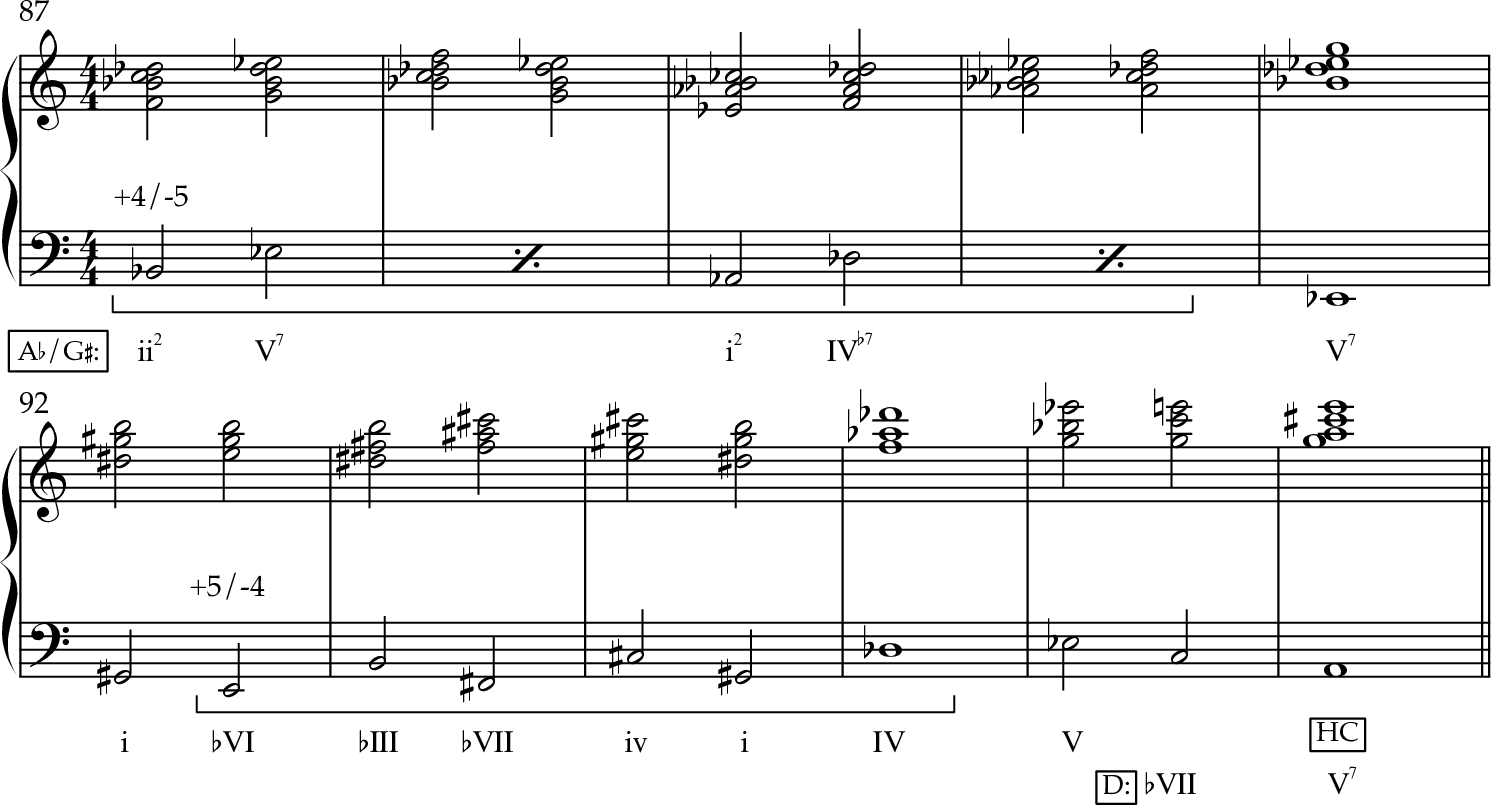

Even the two portions of section B that are not built on a pitch from m. 1 allude to the opening motive. Example 22 shows the opening of theme g, featuring extensive modal mixture ranging from G Mixolydian to G Aeolian. The bass line moves primarily by fifths or fourths in yet another presentation of (027) from theme a. While departing from the original set classes, the flute embraces the original <021> contour for its commentary within each triad. Theme j similarly revolves around motion by fifths, this time mixing modes with spellings traversing A♭ and G♯. As the reduction in Example 23 shows, mm. 87–90 move by descending fifths, while mm. 92–95 reverse to ascending fifths. Added notes, extensive mixture, and the sudden shift to the dominant of D at the end of the phrase separate this passage from a typical sequence in the common-practice period.

The fascination of this movement stems from its exploration of interlocking perfect fifths in a modal landscape. Most passages feature a minor mode or extensive mixture of major and minor. Phrase endings rely more often on note length, dynamics, harmonic rhythm, and change of figuration than on conventional progressions, substituting motion from mediant, submediant, or subtonic to the dominant at many cadences, as shown in Example 20. This avoidance of V–I at phrase endings is particularly noticeable given the saturation of root motion by fifth elsewhere, both in local progressions and between pitch centers. Thus, this movement brings a fresh sound to an old idea, unpacking three notes a fifth apart through motive, harmony, and mode.

Movement III: Allegro giocoso

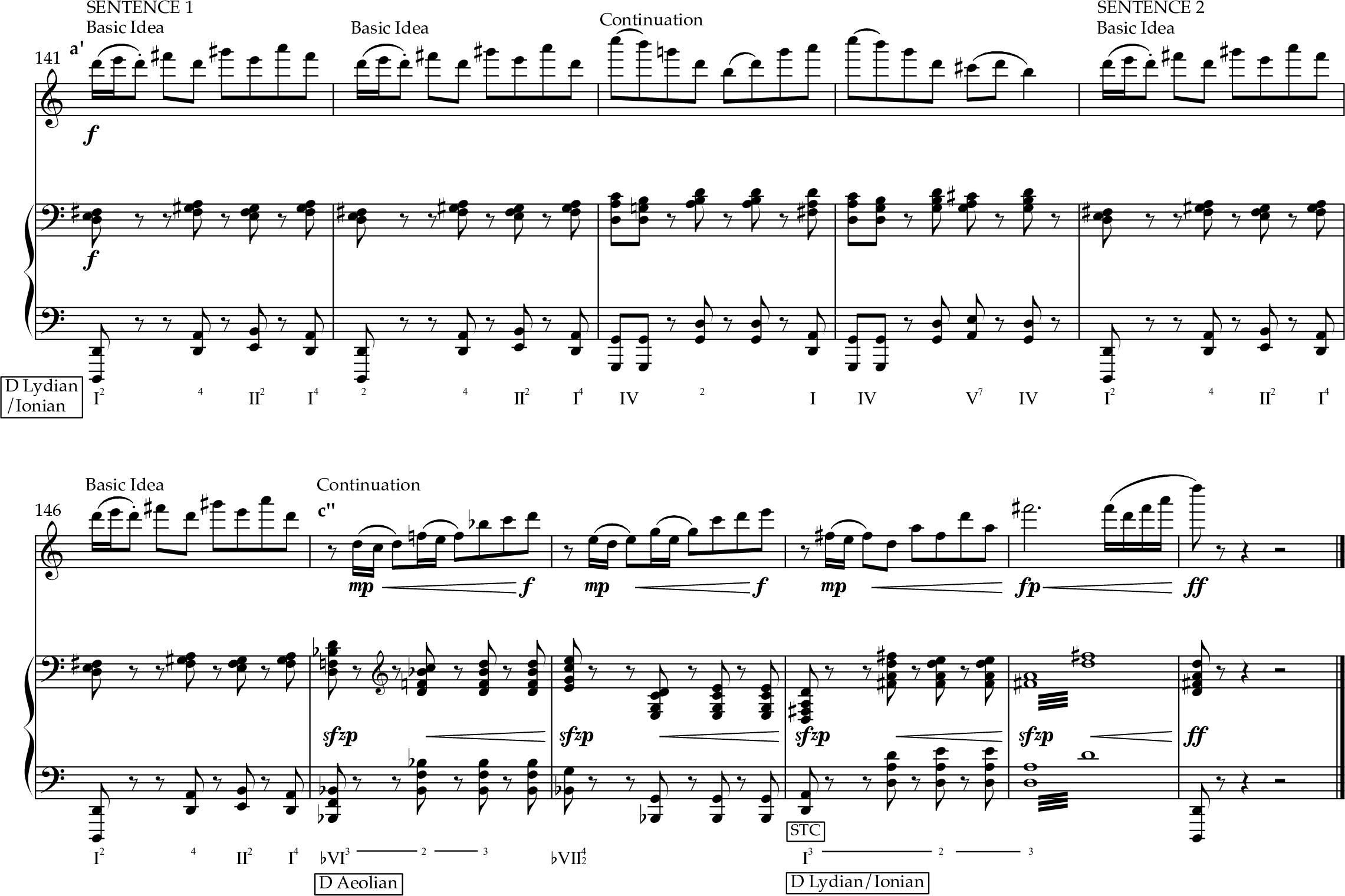

The third movement concludes the work with a fast rondo showcasing the colors of the two instruments. Like the rest of the work, the movement features repetition at the section, theme, and phrase levels as well as pervasive modal mixture. Treatment of large-scale tonality garners particular significance in light of the first movement. Local mixture, sonorities, and motives grow out of the second movement. Together, these features bring the sonata to a satisfying close.

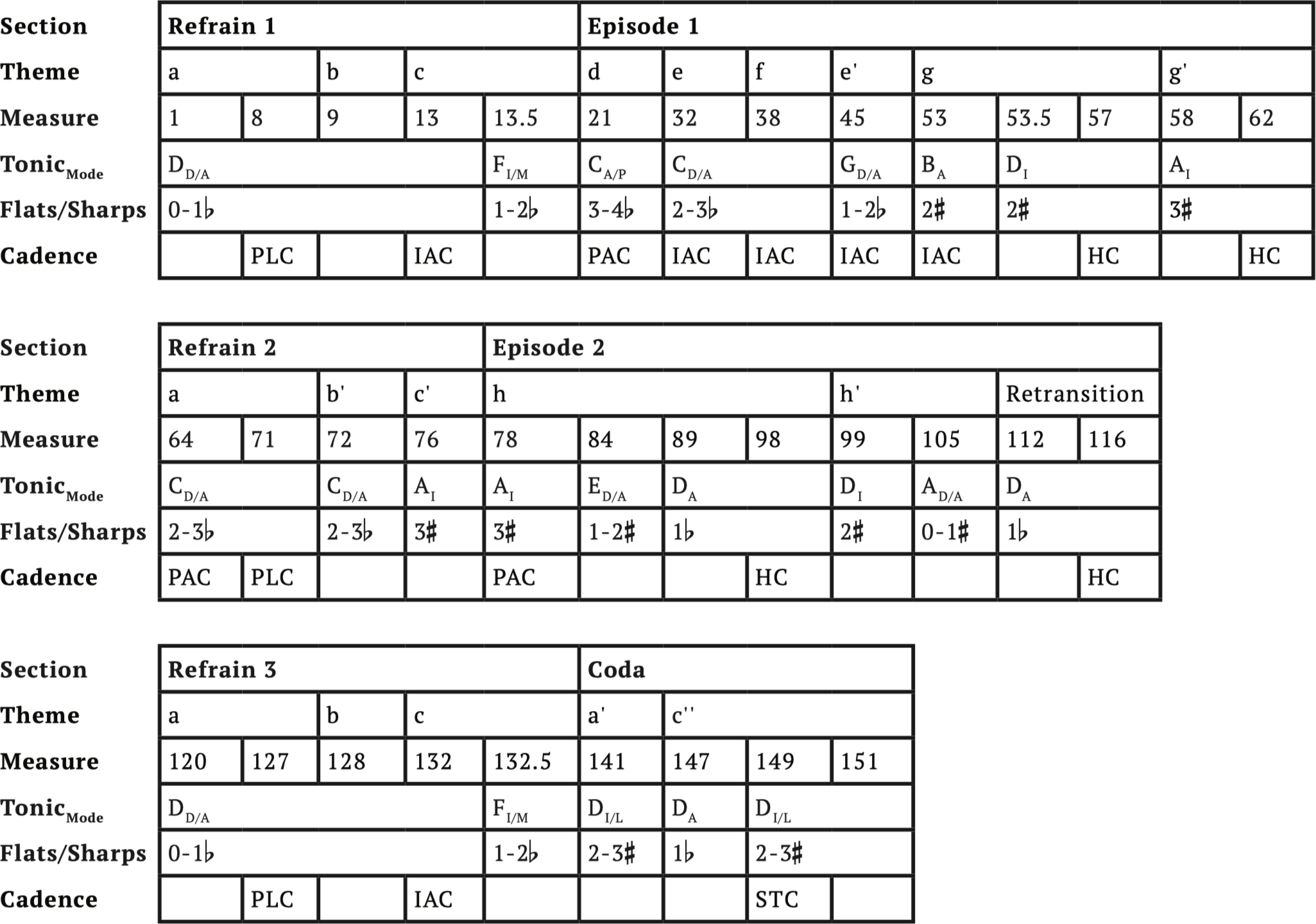

As shown in Example 24, this finale is a five-part rondo with a coda. Section articulations and proportions are more straightforward in this movement than in the second. The three refrains are roughly equal in length. Theme a opens each with a pair of sentences, recalling similar phrase structures in both prior movements. The episodes are roughly the same duration as each other, both more than doubling the number of measures of the refrain. Both episodes contain internal thematic repetition. Episode 1 preserves instrumentation in these repeats, emphasizing the flute in e and e′ and the piano in g and g′. Episode 2 features both instruments in turn in the lyrical heart of the movement, placing the melody in the flute at h and in the piano at h′.

All refrains and episodes feature internal shifts in tonality. The practice of mixing two adjacent modes on the same tonic within a single phrase, which surfaces occasionally in the first movement and more often in the second, increases in the third movement. As Example 24 notes, most passages feature Aeolian mixed with Dorian or Phrygian or, less frequently, Ionian mixed with Mixolydian or Lydian. Double-headed arrows represent this mixture in the tonal trajectories shown in Examples 25, 26, and 27. Comparing the three sections reveals a slight brightening over the course of the movement. Example 25 shows how the first refrain and episode have the greatest variety of collections, ranging from four flats to three sharps. Theme d in episode 1 is the only portion of the piece to touch on Phrygian. The second large section shown in Example 26, the second refrain and episode, keeps A Ionian and its neighbor D Ionian as the scales with the most sharps. This portion only reaches three flats and features more tonalities in sharps. The third refrain with coda further narrows the range of collections to two flats through three sharps, as shown in Example 27. Interestingly, D Lydian substitutes for A Ionian as the three-sharp representative in the coda, combining the opening tonic pitch with the brighter collection.

Tonal trajectories in refrain 1 and episode 1, Ewazen, Sonata No. 1 for Flute and Piano/III.

Tonal trajectories in refrain 2 and episode 2, Ewazen, Sonata No. 1 for Flute and Piano/III.

Tonal trajectories in refrain 3 and coda, Ewazen, Sonata No. 1 for Flute and Piano/III.

The treatment of refrain material in the third movement bears some similarities to the treatment of the main theme in the first movement. The first and third refrains are essentially identical, with the latter ending with a one-bar extension. As shown in Example 24, both pair D Dorian/Aeolian (minor modes) with F Ionian/Mixolydian (major modes). The beginning of refrain 2, like the main theme at the start of the development in the first movement, is transposed down in relation to refrain 1, this time by a whole step. Instead of ascending a minor third as in refrain 1, refrain 2 descends a minor third to A Ionian, the tonality also used at the end of episode 1 and the beginning of episode 2. Like the first movement, the finale announces the coda with a striking change in mode. Example 28 compares the opening of refrain 1 in D Dorian/Aeolian to the coda in D Ionian/Lydian. Moving the flute into its upper octave further accentuates this brightening of mode, driving towards the end of the movement. In general, this move connects to the well-known tradition of minor-to-major narratives in sonatas. See chapter 14 of Hepokoski and Darcy (2006, 306–317). In particular, though, this choice garners significance from its context. The finale is the only of the three movements in this sonata to start and end with the same tonic pitch. Furthermore, by retaining the opening tonic pitch while transforming the mode in the coda, the finale reverses the closing strategy of the first movement. These aspects emphasize completion of this movement as well as the work as a whole.

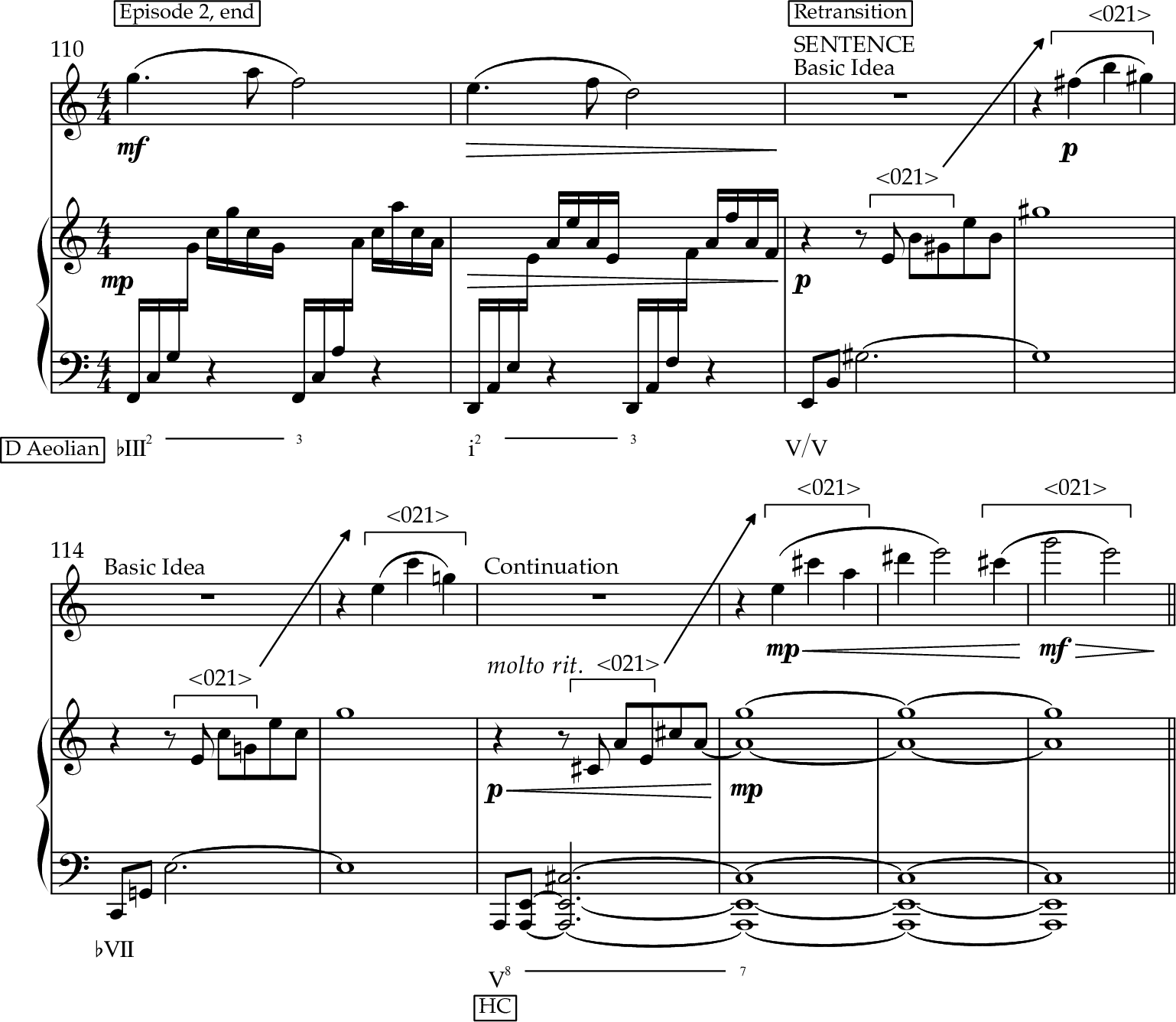

Sonorities and motives connect the second and third movements. As is common in Ewazen’s style, figurations in the second movement occasionally involve a triad with an added second. Examples include m. 12 (Example 17), mm. 87–90 (Example 23), as well as all statements of theme b (Example 19) and the end of the coda. The third movement leans more heavily on such sonorities, including the block chords of theme a shown in Example 28. The voicing and emphasis on parallel motion suggest that the dissonance is derived as an added second rather than a ninth topping a tertian chord. Added seconds also season the harmony of episode 2 in the third movement. Most of those resolve up by step to the third of the triad, as illustrated by the first two measures of Example 29. The remainder of Example 29 shows the retransition preparing for the third statement of the refrain. Built as a sentence, this passage references the three-note motive from the second movement through contour. Brackets mark how the subtle statements in the middle of the piano’s arpeggios are answered by more overt statements in the flute in longer note values. The middle two statements in the flute use the same three pitches as the piano, strengthening the connection between the lines in this passage and solidifying the reference to the second movement.

Working within the traditional rondo framework, the finale interweaves multiple threads from the previous two movements. General characteristics include melodicism, clarity of form at the phrase, theme, and sectional levels, and the care to showcase both instruments. More specific elements include the fluid motion between tonalities within and between phrases and the manner of modal mixture. Tonal transformations in the coda comment on the closing strategy of the first movement, and added-note sonorities and the motivic design of the retransition reference the second movement. The third movement thus continues and concludes strategies introduced in the two prior movements, synthesizing multiple dimensions into a strong conclusion to the work.

Conclusion

Sonata No. 1 for Flute and Piano presents multiple facets of Ewazen’s general compositional approach, documenting the style of one significant living composer popular with both performers and audiences. As Altman (2005, 14) notes, “Ewazen’s music deserves to be studied because it has been of great interest to so many performers and listeners.” As with many of his non-programmatic works, this sonata employs aspects of traditional design that impact motivic development, phrase structure, and large-scale form. Other aspects of the musical language draw from a multitude of twentieth-century influences. Example 30 lists the styles from Part I that likely influenced specific features of this work explored in Part II. As Philip Brown (2009, 137) observes, “Ewazen’s music is remarkably accessible for both the performer and the listener, and his compositions challenge the notion that music has to be obtuse in order to be profound.”

This analysis of Ewazen’s Sonata No. 1 for Flute and Piano documents synthesis of diverse elements into an artistically effective whole. While all three movements invoke traditional formal types, each embraces a fluid approach to tonality at the small and large scales. The first and third movements resolve the main conflict through modal transformation in the coda. The second embraces the simple idea of two perfect fifths as the generator of motive, progression, and key structure in a modal framework. The second and the third share sonorities and motives. These interrelations create an artistically unified and satisfying whole that is effective in performance.

The attraction of contemporary tonal music partially stems from the expressive interweaving of multiple nineteenth- and twentieth-century influences, as Ewazen’s style in general and this sonata in particular illustrate. Unpacking the characteristics of such music as well as their chain of influence deserves greater attention in the field of music theory. Artistry often entails creative recombination of inherited elements, and much remains to be explored in the form and tonality of art music of today.

Works Cited

Altman, Timothy Meyer. 2005. “An Analysis for Performance of Two Chamber Works with Trumpet by Eric Ewazen: . . . to cast a shadow again (a song cycle for voice, trumpet and piano) and Trio for Trumpet, Violin and Piano.” DMA diss., University of Kentucky.

Arnone, Francesca. 2016. “A Sampling of Compelling Flute-Centered Composers.” The Flutist Quarterly 41 (3): 30–36.

Atkinson, Sean E. 2019. “Soaring Through the Sky: Topics and Tropes in Video Game Music.” Music Theory Online 25 (2). https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.19.25.2/mto.19.25.2.atkinson.html.

Aziz, Andrew. 2020. “Temporal Disruptions in Debussy’s and Ravel’s Programmatic Sonata.” Music Analysis 39 (3): 314–58.

Bates, Ian. 2012. “Vaughan Williams’s Five Variants of ‘Dives and Lazarus’: A Study of the Composer’s Approach to Diatonic Organization.” Music Theory Spectrum 34 (1): 34–50.

Biamonte, Nicole. 2010. “Triadic Modal and Pentatonic Patterns in Rock Music.” Music Theory Spectrum 32 (2): 95–110.

Brown, Philip. 2009. “Eric Ewazen.” In A Composer’s Insight: Thoughts, Analysis, and Commentary on Contemporary Masterpieces for Wind Band, Vol. 4, edited by Timothy Salzman, 137–60. Galesville, MD: Meredith Music Publications.

Caplin, William E. 1998. Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. New York: Oxford University Press.

Caplin, William E 2009. “What are Formal Functions?” In Musical Form, Forms, and Formenlehre: Three Methodological Reflections, edited by Pieter Bergé, 21–40. Leuven: Leuven University Press.

Clement, Brett. 2013. “Modal Tonicization in Rock: The Special Case of the Lydian Scale.” Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic 6 (1): 95–141. https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut/vol6/iss1/4.

Clement, Brett. 2019. “Diatonic and Chromatic Tonicization in Rock Music.” Journal of Music Theory 63 (1): 1–33.

Cone, Edward T. 1968. Musical Form and Musical Performance. New York: W. W. Norton.

Duffie, Bruce. 1998. “Composer Eric Ewazen: A Conversation with Bruce Duffie.” https://www.bruceduffie.com/ewazen2.html.

Everett, Walter. 2004. “Making Sense of Rock’s Tonal Systems.” Music Theory Online 10 (4). https://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.04.10.4/mto.04.10.4.w_everett.html.

Ewazen, Eric. 1997. Sonata for Trumpet and Piano. Southern Music Company.

Ewazen, Eric. 1998. Sonata for Horn and Piano. Southern Music Company.

Ewazen, Eric. 2011. Sonata No. 1 for Flute and Piano. Theodore Presser Company.

Ewazen, Eric. 2013. Sonata No. 2 for Flute and Piano. Theodore Presser Company.

Ewazen, Eric. 2016. Sonata for Euphonium and Piano. Theodore Presser Company.

Ewazen, Eric. n.d. “Music.” The Music of Eric Ewazen. https://www.ericewazen.com/themusic.php.

Feldman, Evan. 2015. “Ewazen, Eric.” Grove Music Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.A2284315.

Harrison, Daniel. 2016. Pieces of Tradition: An Analysis of Contemporary Tonal Music. New York: Oxford University Press.

Heinzelmann, Sigrun B. 2011. “Playing with Models: Sonata Form in Ravel’s String Quartet and Piano Trio.” In Unmasking Ravel: New Perspectives on the Music, edited by Peter Kaminsky, 143–79. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

Hepokoski, James. 2002. “Beyond the Sonata Principle.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 55: 91–154.

Hepokoski, James and Warren Darcy. 2006. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata. New York: Oxford University Press.

HipBoneMusic. 2017. “Bone2Pick: Eric Ewazen Interview.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I6xGmv8SZy0.

Hook, Julian. 2008. “Signature Transformations.” In Music Theory and Mathematics: Chords, Collections, and Transformations, edited by Jack Douthett, Martha M. Hyde, and Charles J. Smith, 137–160. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

Hyer, Brian. 2001. “Tonality.” Grove Music Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.28102.

Kaminsky, Peter. 2011. “Ravel’s Approach to Formal Process: Comparisons and Contexts.” In Unmasking Ravel: New Perspectives on the Music, edited by Peter Kaminsky, 85–110. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

Lam, Nathan L. 2019. “Relative Diatonic Modality in Extended Common-Practice Music.” PhD diss., Indiana University.

Lehman, Frank. 2018. Hollywood Harmony: Musical Wonder and the Sound of the Cinema. New York: Oxford University Press.

Madden, John T. 2002. “An Interview with Eric Ewazen.” Journal of the World Association for Symphonic Bands and Ensembles 9: 135–41.

McNally III, Joseph Daniel. 2008. “A Performer’s Analysis of Eric Ewazen’s Sonata for Trumpet and Piano.” DMA diss., University of Southern Mississippi.

Osborn, Brad. 2017. “Rock Harmony Reconsidered: Tonal, Modal, and Contrapuntal Voice-Leading Systems in Radiohead.” Music Analysis 36 (1): 59–93.

Page, Tim. 1986. “Music: Works by Ewazen.” New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1986/10/02/arts/music-works-by-ewazen.html.

Pettit, Heather. 2003. “With Band Music Eric Ewazen is Like a Child in a Candy Store.” Instrumentalist 57 (9): 32–39.

Schmidt-Best, Thomas. 2011. The Sonata. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schneller, Tom. 2013. “Modal Interchange and Semantic Resonance in Themes by John Williams.” Journal of Film Music 6 (1): 49–74.

Snedecker, Jeffrey. 2001. “The Color of Brass: An Interview with Eric Ewazen.” The Horn Call: Journal of the International Horn Society 32 (1): 33–34.

Straus, Joseph N. 2016. Introduction to Post-Tonal Theory. 4th edition. New York: W. W. Norton.

Temperley, David. 2018. The Musical Language of Rock. New York: Oxford University Press.

Webster, James. 1978. “Schubert’s Sonata Form and Brahms’s First Maturity.” 19th-Century Music 2 (1): 18–35.