Few composers can lay a stronger claim to be among the fathers of American art music than William Grant Still. His music’s enormous popularity in the 1930s and 1940s, in combination with its consummate craftsmanship, cemented his lasting reputation as not only the “Dean of Afro-American Composers” but as one of America’s greatest musical minds. It is unfortunate that his music has not received more thorough analysis, but perhaps one reason for this, among others, is the music’s optimistic pluralism, which confounds facile musical (and extra-musical) analysis. In Still’s music reside three desires: to follow in the tradition of European art music; to produce a distinctly African-American art music; and to engage, however ambivalently, with the growing international modernist movement. His 1947 Fourth Symphony—titled “Autochthonous” by Still—grapples meaningfully with these three impulses, revealing hidden affinities while attempting to produce what Still called a “universal” style. In order to demonstrate how Still’s mature style combines the three key influences—European art music tradition, African-American tradition, and modernism—I will examine the first movement of the Fourth Symphony. Still’s music and writings demonstrate a devotion to European art music and the Black experience. To illustrate this, I provide a musical and social context for Still’s late style and stylistic evolution, and I propose musical features that represent the three influences and document their roles in the first movement of the Fourth Symphony. By considering the movement and its narrative as a whole, I will conclude by reflecting on the music’s combination of diverse influences, its supposed universality, and its relationship to the music of Still’s contemporaries.

Still's Music: Musical and Social Contexts

Still’s music has often been cited as being conspicuously “American.” Verna Arvey, Still’s wife and collaborator, considered his music to exemplify American pluralism:

More than a quarter of a century ago, North Americans were busily engaged in a search for a serious composer whose works would most accurately reflect their country in music . . . It seemed to some searchers that perhaps a blend of all types of music would best represent the melting pot that is the U.S.A. . . . Small wonder that when audiences abroad hear [Still’s] music, they are apt to recognize it immediately as being a product of the North American continent. Some European critics have described it as the most “indigenous” music to come out of North America. (1972, 82)

Robert Bartlett Haas, the well-known educator and specialist in American modernist literature, similarly sees Still’s music as an influential contribution that synthesizes Black and White musical cultures: “The militants claim he is writing ‘Eur-American,’ not ‘Afro-American’ music, but this is not an historically accurate statement. Hale Smith, Ulysses Kay, Arthur Cunningham, Olly Wilson, and others, Black composers, avant-garde to a greater or lesser degree, all recognize Still as a pioneer” (1972, 2). Still’s music has been widely recognized as sounding specifically American while also laying the foundation for generations of more experimental Black composers who followed.

More recently, scholars have sought to contextualize Still’s pioneering musical efforts within the world of American music in the first half of the twentieth century. Gayle Murchison groups Still’s output—following his own analysis—into three periods: an early “ultramodern” period, a period dominated by a “racial idiom,” and a period dominated by a “universal idiom,” which is a synthesis of the two previous styles combined with European common-practice elements Still developed while studying at Oberlin (2000, 48). Catherine Parsons Smith similarly sees Still’s career as an expression of a characteristically American pluralism: “[Still’s] identification as an African American who confounded a range of sometimes conflicting popular stereotypes—raised in an urban Southern environment in a tight-knit family with aspirations to uplift the race; active and successful in the separate, culturally opposed worlds of commercial and concert music; more the modernist and Harlem Renaissance man than he would have cared to admit, self-exile notwithstanding—assured that his aesthetic synthesis would be a unique and valuable contribution to American culture.” (2000, 204). Still’s professional background and aesthetics owe much to balancing different musical, financial, and political demands, and the success with which he did so early in his career informed the development of his musical style.

Still’s compositional style evolved gradually until he settled into a more universalist mature style. After initial forays into music, Still studied at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music, where he absorbed common-practice European compositional practice. It was his move to New York in 1919, however, that would unveil new musical horizons. Working at first primarily as a jazz arranger, Still gained access to larger orchestras and experimented with novel arrangements. The popularity of the shows to which he contributed— including Rain or Shine, Dixie to Broadway, and The Earl Carroll Vanities—provided him with recognition and what he may have considered to be lucre, since he remained determined to escape the world of commercial music. According to Griffith Edwards: “Still was too conscious of the vernacular music not being recognized to see early jazz as Afro-America’s ultimate identity in music. Jazz ‘is not our most important contribution,’ he maintained. ‘It simply happens to be the one fortunate enough to have secured the most extensive financial backing’” (1987, 70, emphasis in the original). His early exposure and mastery of popular music forms, however, were certainly formative.

It was Still’s two-year apprenticeship with Edgar Varèse beginning in 1923 that would fundamentally alter his compositional destiny. Though Still was deeply critical of the musical avant-garde later in life, Varèse opened compositional and professional doors previously closed to him. Through Varèse, Still met Leopold Stokowski, Howard Hanson, Arnold Schoenberg, Ottorino Respighi and others (Edwards 1987, 75). Still composed several pieces under the influence of Varèse’s modernist aesthetics, but according to Edwards, Varèse’s ultimate influence was “to help him find for himself the artistic abilities and the personal mission with which he could balance and shape the lessons of his youth.” (1987, 78). Nevertheless, Still’s early brush with musical modernism cannot be easily dismissed: as we shall see, modernist techniques exist alongside others in Still’s mature work. Smith argues that Still’s eventual break with Varèse, and by extension the major modernist figures of the day, was motivated by his desire to create “a ‘serious’ African American Style [that] could not, by its nature, use much of the ultramodern dissonance to which Varèse had introduced him and at the same time reach the audience with which he sought to communicate . . . Still was clearly influenced . . . by the New Negro movement, even though his association with it was often more a matter of geographic and social proximity than direct, self-conscious intellectual participation.” (2000, 71-72)

Alongside his study of modernist techniques developed primarily by white composers in New York, Still encountered the nascent, burgeoning Harlem Renaissance. The publication of Alain Locke’s The New Negro in 1925 spurred a determination in Black America and throughout the African diaspora to create a new, authentic artistic culture that assimilated the totality of Black experience, from nineteenth-century African-American nationalism to slavery and liberation, along with the exodus out of the agrarian South to the boisterous urban North (1997 [1925], 256). But Locke’s seminal work capped what had already been decades of internal debate amongst scholars, artists, and political leaders. Belying the concerted front that desired political reform and new artistic expression, those with competing visions for what African-American art should look like engaged in heady debate. Informing one perspective was W.E.B. Du Bois’s vision for Black education, which would unlock new artistic vistas and social opportunity by combining training in common-practice European techniques with Black experience:

Above our modern socialism, and out of worship of the mass, must persist and evolve that higher individualism which the centres of culture protect; there must come a loftier respect for the sovereign human soul that seeks to know itself and the world about it; that seeks a freedom for expansion and self-development; that will love and labor in its own way, untrammeled alike by old and new . . . Herein the longing of black men must have respect: the rich and bitter depth of their experience, the unknown treasures of their inner life, the strange rendings of nature they have seen, may give the world new points of view . . . I sit with Shakespeare and he winces not. Across the color line I move arm in arm with Balzac and Dumas, where smiling men and welcoming women glide in gilded halls . . . So, wed with Truth, I dwell above the Veil. Is this the life you grudge us, O knightly America? (2018 [1903], 85–86)

Du Bois’s perspective blends the need to educate Black youths using the same classical materials and techniques, though not exclusively, that served their white peers and that they were outrageously denied.

In contrast, Langston Hughes later famously approached the problem of Black cultural identity by arguing that Black artists need be proud of their own history, experience, and institutions:

I am ashamed for the black poet who says, “I want to be a poet, not a Negro poet,” as though his own racial world were not as interesting as any other world. I am ashamed, too, for the colored artist who runs from the painting of Negro faces to the painting of sunsets after the manner of the academicians because he fears the strange unwhiteness of his own features. An artist must be free to choose what he does, certainly, but he must also never be afraid to do what he must choose. (1999 [1926], 56)

Caught in the middle, Still had experimented with these two sides of the multifaceted debate, having been a student at Oberlin—the ne plus ultra of a musical academy—and an active and highly successful jazz musician, and having left Arkansas for New York and Boston. According to Murchison, Still exemplified the Harlem Renaissance’s search for the new man:

Music was central to Locke’s beliefs about the cultural strivings of the New Negro. Locke concurred with Du Bois that the spirituals were truly American, the gift of the Negro to American music, and were expressive of African American life, culture, history, and condition . . . Although Locke acknowledged that the masses were on the vanguard of change in African American life (e.g., migrations, vernacular music such as folk traditions, jazz and blues, and other vernacular culture), it was not folk music or popular music that would be redemptive in his vision of artistic culture. Rather, it was genius . . . who should use the spirituals and other black vernacular musical idioms as a resource to create the foundation for an African American art music. Locke cast Still in this role. (2000, 47)

Still produced overtly “racial” pieces in the late 1920s and early ’30s, but he ultimately became dissatisfied with the limitations of producing such music. Carol Oja characterizes the conflict facing Still as one common to many Black artists in the 1920s:

For Black artists this strong interest in Negro culture resulted in a tension between devising work that was identifiably African-American and following their own artistic vision. Sometimes the two coexisted comfortably, sometimes they did not . . . The conflict between a more dissonant—or “ultramodern”—musical style and an identifiably black one became central to Still’s music in the years ahead. If his works leaned too far in the first direction, he faced the same kinds of criticisms hurled at all the young American modernists . . . if Still incorporated all aspects of a given African-American idiom—melodic, formal, and especially harmonic—he risked having his music viewed as “simple” or “filled with naïveté” . . . Fusing the modernist with the racial, his pieces continued to be promoted by new music organizations. (1992, 154–55)

Still’s solution to the problem was to attempt to define a more universal musical language that combined common-practice, modernist, and non-Western (in his case, specifically Black) elements to produce a musical whole readily understood by the public. And his refusal to choose between a common-practice informed style and explicitly racial music is perhaps also echoed in his move to and final settlement in Los Angeles in the 1930s—a westward peregrination that itself mythically characterizes American individualism and enterprise. For much more on the socio-political and musical motivations for Still’s move to Los Angeles, see DjeDje 2000. Still was likely motivated to move there because of growing disillusionment with musical life in New York and because of the high concentration of diverse and talented musicians working in Hollywood. At the time, however, it was still a risky adventure, and so the echoes of Greeley’s famous advice, “Go west, young man,” despite Still’s more advanced age, are impossible to ignore.

Still’s vision for Black musical education combines Du Bois’s esteem for Euro-American art music tradition with Hughes’s desire for sincere study of Black contributions to American music, as he wrote:

In the first place, I would suggest that students who want to learn about Negro music should undertake it in all sincerity, not with the idea that they are taking a snap course, or that they will be permitted to sit and listen to jazz recordings during every class period. This may be enjoyable, but it is not genuine study. The latter in my opinion should be historical, analytical, comparative, and should be undertaken above all with an open mind . . . Along with this, the Negro student of music should learn Bach, “that old, dead punk,” and all the other composers who have made valuable contributions to music. (Spencer 1992, 223)

His reflections on being a composer similarly call for the need for Black composers to achieve individuality:

I had chosen a definite goal, namely, to elevate Negro musical idioms to a position of dignity and effectiveness in the fields of symphonic and operatic music . . . American music is a composite of all the idioms of all the people comprising this nation, just as most Afro-Americans who are ‘officially’ classed as Negroes are products of the mingling of several bloods. This makes us individuals, and that is how we should function, musically and otherwise. (Spencer, 1992, 225–6, emphasis in the original)

It is abundantly clear that Still and his many interpreters see his music as embodying American music’s pluralism and its ability to foster novelty by synthesizing received traditions. Still’s own words attest to his vision for his music’s place in American culture. He waxes prophetic while imagining the future of American music: “We have in the United States a great many idioms, some aboriginal, some springing from the people who came here from other lands. Someday probably the separate idioms in America may merge, or a composer will come along who will make an overall use of them and we will then have a distinctly native idiom, recognizable as such” (Spencer 1992, 120). For Still, the ideal of producing a distinctly “native” idiom lies in the future, and his role was to act as a contributor to its creation. The Fourth Symphony is a particularly exemplary work of Still’s universalist style. Its subtitle, “autochthonous,” immediately establishes the work’s aim: to produce a music that emerges from and could only emerge from American soil. The word “autochthonous” comes to us from Ancient Greece where it applied to the indigenous inhabitants of a territory as opposed to colonists or settlers and their descendants—autochthonous individuals are products of the soil itself. Still’s use of the term suggests a metaphorical autochthony as opposed to a literal one, since, while he alludes to the truly autochthonous music of American aboriginals, his artistic vision combines it with the music of the descendants of colonists, immigrants, and slaves. While “autochthony” also had darker, proto-nationalistic connotations, it is clear that Still intends for the word to connote inclusivity and pluralism. For more on the term and its Athenian roots, see Blok 2009. Still was surely not oblivious to the apparent paradoxes: the conflict between a “native” music and a “universalist” idiom, and between an already-extant “aboriginal” idiom and a “distinctly native idiom” that has yet to be born. As we examine the piece in greater detail below, we will see how Still reconciles the two, often by implying or arguing that an autochthonous American music is by nature universal since it interweaves seemingly disparate cultural threads into a complete tapestry.

European Art-Music Tradition, Modernism, and African(-American) Elements

Still’s success at creating a uniquely pluralist American art music derives from his triangulation of three stylistic elements: European art-music tradition, modernism, and African-American elements. All three elements are present in the Fourth Symphony. I will briefly describe and define these three elements before pursuing them analytically in greater detail in the next section.

Several features bind Still’s work to the European art-music tradition: its form, genre, motivic construction, and use of common-practice tonality. Still titles the work a “symphony,” and the work contains the traditional four movements: sonata-allegro, adagio, dance movement, and finale. The first movement, which forms the focus of my analysis, adheres closely to sonata form: the work is thoroughly tonal and can be analyzed from a tonal-functional point of view with relative ease.

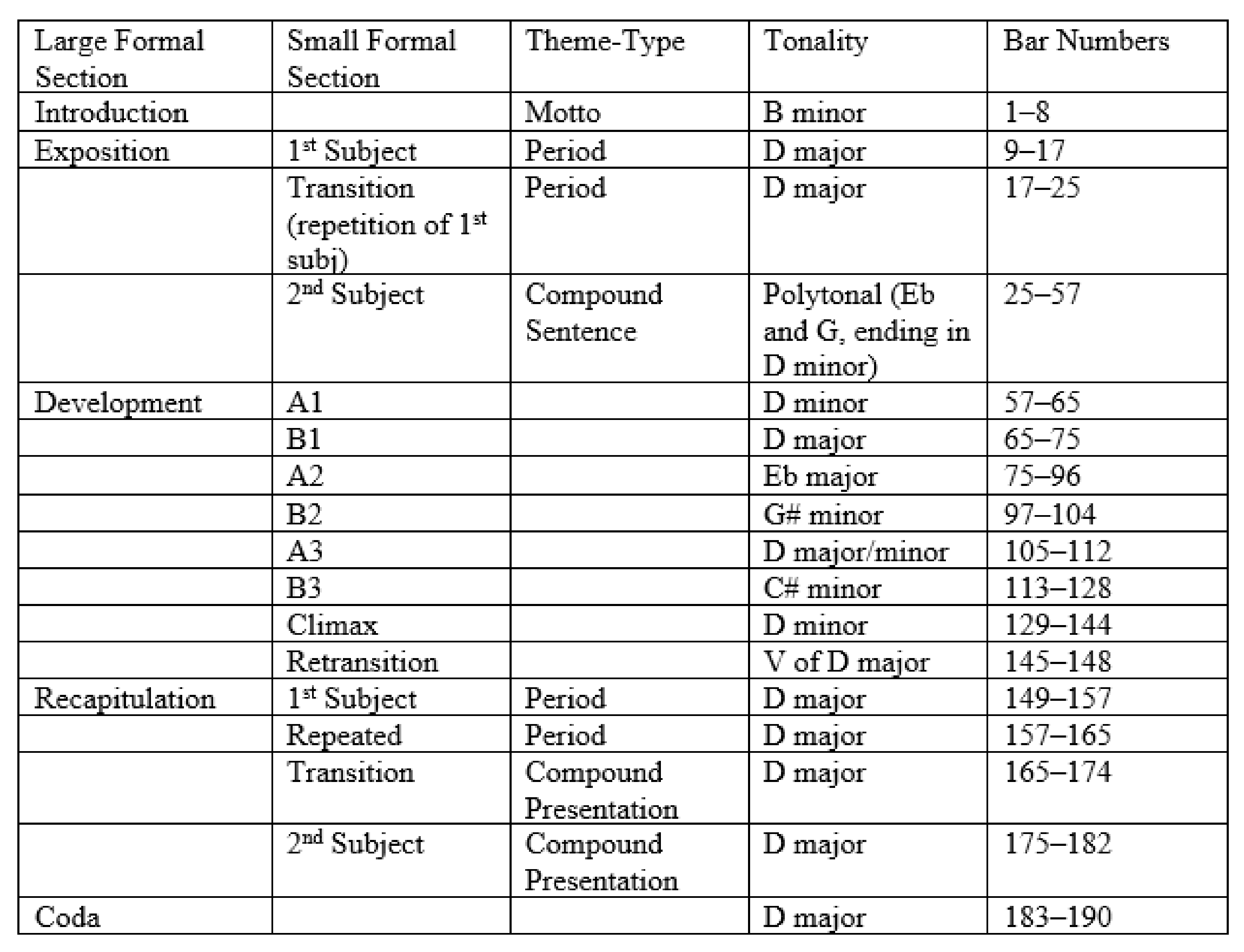

Example 1 provides a reading of the piece’s form. The movement’s first subject is a classical period in D major; its repetition functions as a transition to the second subject; the second subject contrasts tonally and thematically with the first; the development section contrasts the exposition’s thematic ideas with newer material while exploring keys related more distantly to the global tonic; and the recapitulation, while mightily compressed, restates both subjects in the home key. Haas describes the movement as being formally “free” while alluding to sonata-allegro form (1987, 43) and somewhat mystifyingly claims that the piece proceeds from D major to C major to D major. I believe the piece adheres rather closely to sonata form. Still himself wrote that while sketching a new piece “my usual practice is to map out a plan which conforms loosely to the established rules of musical form, and then deviate from it as I see fit.” (1987a, 109). His statement implies that he uses sonata form as a generic backdrop for his music despite superficial deviations from established norms. I will return to a closer reading of the piece’s form below.

The piece also engages with familiar organicist traits long identified with the aesthetics of analysts and composers of Western music, particularly beginning in the nineteenth century and climaxing in the early twentieth century. For more on organicism in music and its relationship to philosophy and the arts, see Solie 1980 and Neubauer 2009. While organicism is frequently described in Western philosophical terms—where it begins with Aristotle, passes through German romanticism to Spengler, and continues to influence contemporary thought—what Thorsten Botz-Bornstein describes as “micro-macro” thought is common also to non-Western culture. Botz-Bornstein interprets organicist thought in Chinese, Japanese, Russian, Arab, and Bantu cultures: the Bantu concept of ugumwe—roughly, “oneness”—denotes a political, collective solidarity between members of families, clans, and tribes (127). Still acknowledges the influence of an “organicist” approach to manipulating thematic material:

There must be a recurrence of thematic material in any musical composition before any listener, trained or untrained, can detect the form, or plan, that underlies the work. This recurrence of theme brings a well-defined unity . . . The classic masters believed that they had to hammer away at a theme in order to drive it into people’s consciousness. I agree with them, except I do not believe in exact repetitions . . . In composing, I prefer to have shorter themes than the masters usually employed, so as not to tax the memory, and to repeat these shorter themes often, with alterations.” (Spencer 1992, 175–176)

Still’s need to vary material echoes the symphonic forms of Brahms and Mahler whose music Ruth A. Solie describes as typical of romantic organicist thought. Still’s variation process also reflects Samuel Coleridge Taylor’s view that “a work of art considered as a living being, then, will be evaluated, similarly, in terms of multiplicity-in-unity” (Solie 1980, 148). Example 2 provides the primary thematic material for the whole movement. Its opening motto contains three motives—x, y, and z—which are used to build the first and second subjects. My approach to thematic transformation is indebted to Rudolph Reti’s (1951) method in which the motives comprising a larger theme may be freely rearranged (“interverted”) and varied. Reti contends that thematic transformations and relationships of this sort are central to the aesthetics of post-Beethovenian organic form, in which small motives mutate and grow across a work—a thematic conception eerily similar to Still’s own above. Solie (1980) argues that Reti’s method exemplifies organicist conceptualization and analysis of music. More recent motivic theories similarly consider permutation and more distant motivic relationships; see for example Auerbach 2021. The first subject begins with motive z (without the note E and rhythmically varied), continues with a rhythmic variation of motive x transposed to D, and ends with a loose augmentation of motive y. The second subject begins with motive x transposed to G followed by a variation of motive y, in which the initial descending interval is changed from a whole tone to a major third and in which the final note enters an eighth note earlier.

Still’s evocation of African and African-American music manifests in four critical domains: modality, thematic material, harmonic parallelism, and rhythm. The motto, first subject, and second subject are all drawn from the major pentatonic scale. Musicologists and ethnomusicologists working in the first half of the twentieth century identified the pentatonic scale as an African contribution to African-American music. The pentatonic collection can also be found in other American music from the first half of the twentieth century, for example in the music of Aaron Copland, see Heertderks (2011). The music likely borrows from or alludes to African contributions to American music. More recently, Christopher Jenkins has traced the use of the pentatonic scale in Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson’s chamber music, where he argues that it evokes African-American musical practice. Jenkins defines “signifyin(g) broadly as “a mode of indirect and/or coded communication, intended to convey multiple meanings specific to various in-groups with access to specialized information . . . repetition is a key aspect of signifyin(g), often (but not always) through the repeated presentation of a representation figure alluding to source material in an original context but overlaid by a shifting accompaniment. Through the presentation of representational material in difference contexts, our understanding of its meaning changes” (2019, 392). In Jenkins’ analysis of Perkinson’s Lament for viola and piano, he observes that a syncopated, pentatonic viola line is set against a rhythmically regular piano accompaniment which frequently supports the tune with chromatic, at times dissonant harmonies: “Given the emphasis . . . on repetition as a central trope within the constellation of signifyin(g) practices, it seems clear that through his repetition of the D minor pentatonic scale in a constantly syncopated solo line, Perkinson is signifyin(g) upon both the pentatonic scale as a building block in African American music and the concept of syncopation, as the viola remains rhythmically disjunct from the regular eighth notes of the piano” (2019, 398). Still’s symphony similarly contrasts syncopated pentatonic material with metrically regular chromatic accompaniments, and he achieves a similar effect: the pentatonic source material coexists with the traditional symphonic and modernist elements in the piece, and their relationship to one another becomes one of the focal points of the piece.

Still also references harmonic and voice-leading qualities common to African music and jazz. Gerhard Kubik (1994) describes the widespread practice of “homophonic multi-part singing” in sub-Saharan Africa, both in the western and eastern parts of the continent. Scales vary by location, ranging from the major pentatonic to more extended scales whose pitches relate closely to the harmonic series. See for instance Kubik’s discussion of the Gogo tone system which includes at least seven pitches corresponding closely to the harmonic series (1994, 179) as well as hexatonic and heptatonic scales found in Cameroon, Angola, and Zambia (1994, 174). In many of these cultures, singers sing in parallel dyads or trichords such that two scale degrees separate each voice—the size of the intervallic spacing of the voices depends on the particular scale used. A pentatonic scale will produce dyads of a third or fourth when two voices traverse the scale. Vertical intervals include thirds, fourths, fifths, tritones, and mixtures of these intervals. Still’s music frequently makes use of parallel harmony, and his employ of different scales—whether diatonic, blues, or polytonal—produces different vertical intervals.

The symphony’s modernist traits are less conspicuous but nonetheless central to Still’s aesthetic. Still may have ultimately rejected Varèse’s tutelage, but his music retains an expanded harmonic palette. While the first movement of the Fourth Symphony is tonal, it avails itself of harmonic innovations associated with modernist tonal and post-tonal repertories. Still alternates, as we shall see, between passages exhibiting relatively clear tonal functions and those dominated by polytonality. Other passages contain discordant sonorities whose tonal meanings hinge on chromatic voice-leading techniques. Still also adjusts the symphony’s form: within the traditional sonata-allegro exposition, he diminishes the tonal contrast in the exposition in favor of harmonic, rhythmic, and orchestration contrasts—in other words, the three stylistic influences themselves become the focus of the sonata form’s dialectics instead of simple themes and motives.

Still’s project, which combines European art-music tradition, African-American, and more contemporary compositional techniques, is itself modernist in conception. Modernist works, especially in literature, have long been considered to contain multiple voices, producing a stylistic polyphony that captures the experience of a wide range of characters and perspectives. Writing about the modernist novel, Stephen Kern argues that “modernists also developed a range of voices to tell the many ways their narrators knew, or did not know, what their characters were doing and why. Thus, the polyvision and polyphony of modernist narrators aligned with their multiple ways of knowing . . . [modernists] devised a variety of restricted and multiple ways of viewing characters and events through singular, serial, parallel, and embedded focalizations” (2011, 179–180). In Still’s symphony, the voices of European symphonists from Beethoven to Bruckner, the voices of Black musicians from New York City jazz musicians to traditional West African musicians upon whose contributions jazz is founded, and the voices of city and country blend in superimposition, develop serially in separation, and eventually merge to produce Still’s portrait of what he envisioned to be a distinctly American music throughout the course of the symphony’s first movement.

Finally, the three elements are not entirely discrete—there is significant overlap between them, and Still’s style owes some of its success and his generally optimistic perspective owes some of its power to his ability to blur the perhaps too rigid boundaries separating seemingly different artistic worlds. In Still’s music, we hear the connections between the common-practice tradition and modernism, between White and Black, and between the high-minded, “cerebral” (to use Still’s word) world of modernist experimentation and commercial and folk music in several musical domains. Complex, layered polyrhythms allude to sub-Saharan drumming and late nineteenth-century ragtime music but also to the hemiolas of Brahms. David Temperley has noted that syncopations, especially anticipatory ones, are commonly found in late 19^th^-century ragtime music and in recordings made contemporaneously by African-American singers (2021). Kubik (1994) similarly traces syncopation practices in a wide variety of sub-Saharan African cultures. Harmonic planing evokes faux-bourdon as well as African harmonic parallelism, and Still’s use of this technique further references the European art music tradition, African tradition, and modernism by employing parallel harmonies in both functional and polytonal settings. The small set of melodic cells undergoing “genetic” mutation recalls romantic organicism but also the improvisatory foundation of jazz and central African music, Numerous sources describe both variation techniques in jazz, West African, and sub-Saharan music, see William Austin (1966), Gunther Schuller (1968), Gerhard Kubik (1994), and especially Simha Arom (1993), who argues that sub-Saharan music is frequently characterized by a “cyclic structure that generates numerous improvised variations: repetition and variation is one of the most fundamental principles of all Central African musics, as indeed of many other musics in Black Africa” (134). Clearly, the “unity-in-diversity” principle of organicism does not belong solely to Europe. The symphonic form is the ideal canvas upon which Still can paint his vision for a new music assembled from the old.

The First Movement of the Fourth Symphony as a Whole

a) Overview

The three facets of Still’s style discussed above intermingle and develop in the first movement of the Fourth Symphony. Still’s pluralistic compositional approach necessarily requires a pluralistic analytical attitude, and so, in the following analysis, I will make use of many different analytical techniques, tools, and techniques. While some of these techniques are not often presented simultaneously in analysis, the varied nature of Still’s writing requires a similarly flexible analytical attitude. I hope that the analysis will illustrate how comprehensively Still’s music engages with different aesthetics and how successfully they blend into a coherent and rewarding musical experience.

Returning to Example 1, let us consider the large-scale narrative structure of the work. The introduction provides the foundation for the movement as a whole. Its D major–B minor tonality, pentatonic motives, and consistent quarter-note and later eighth-note motion become omnipresent features of the whole piece. The exposition separates the three motives and shapes them into contrasting thematic areas that are defined by the predominance of common-practice, modernist, or African-American techniques. The first subject—with its pentatonic melody, syncopations, harmonic parallelism, and functional harmony—contains primarily common-practice tonal and African-American elements. The second subject is much more chromatic, exhibits polytonality and non-functional chord progressions, and contains a high degree of orchestral stratification with little doubling.

The development further striates the stylistic elements and explores them more independently of one another and in new combinations. The development also introduces new thematic ideas and pitch relationships, emphasizing primarily the new role of a tritone. Its climax attains a negativity in which the movement achieves its thickest, loudest, most motivically saturated moment but is marked as a problem by virtue of its minor mode and the presence of melodic and harmonic dissonances that demands resolution in the recapitulation and coda. Still’s solution, as we shall see, is to increase the influence each musical style and theme has on the others, so that the dissonant tritone material from the development supports progressions in what was formerly a mostly diatonic first subject and transition, while the polytonality of the second subject is largely ironed out. The coda brings all the instrumental families together for a massive tutti whose D-major superimposition of themes and syncopated ostinati answers the development’s D-minor climax optimistically.

b) First Subject and Transition

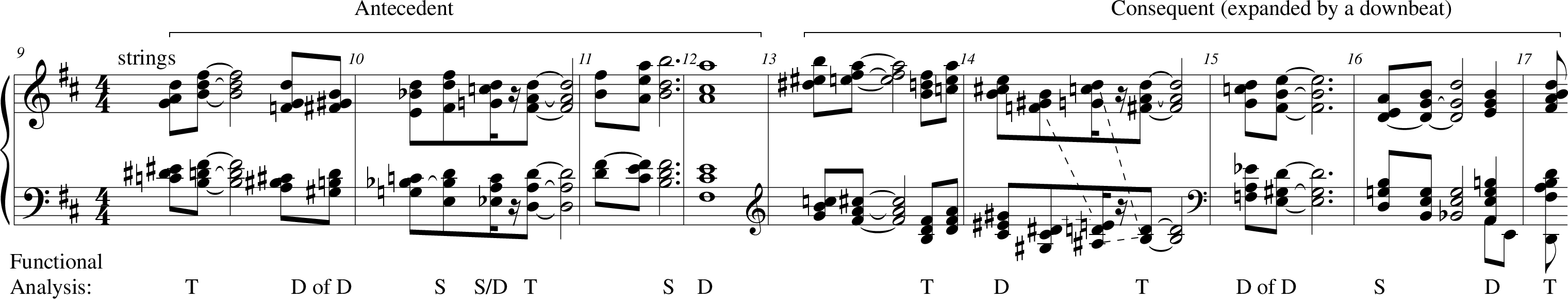

Example 3 provides a piano reduction of the first subject, mm. 9–17, and annotates its form and harmony. While the theme is in most respects a conventional period, its harmonic language— which is tonal-functional, adhering closely to the Riemannian cadence T–S–D–T—introduces some subtle dissonances that will develop further in the second subject and development section. The example labels the harmonies from a functional perspective—the presence of more complex chords makes applying simple Roman numerals more difficult, though not impossible. The antecedent phrase ends with a iii7 chord that functions as a varied dominant in D major, and the opening vi chord stands in for the tonic. Dissonant sonorities often precede the more readily identifiable functional ones. Still produces dissonant harmonies by preceding most consonant chords with sonorities formed by incomplete chromatic neighbor tones and emphasizes the dissonances by placing them in strong metrical positions. The sonority that precedes the B-minor triad on the second eighth note of beat 1 contains {C, D♯, E♯, G, A, D}. The meaning of the sonority is clarified through the stepwise resolution of its literal and implied voice leading: C–B, D♯–D, E♯–F♯, G–F♯, and A–B. The first and last pairs of pitches listed together suggest a Phrygian cadence, which is replicated halfway through m. 10, now applied to a D-major triad, and at the beginning of m. 13, now applied to a F♯-minor seventh chord. While such stepwise displacements of more concordant sonorities are hardly new, the discordant sonorities formed by them introduce a piquant harmonic twist that enriches the otherwise diatonic harmony, while also providing fodder for the more dissonant, strident development section (discussed below). Simultaneous appoggiaturas may be found, for example, in Mozart’s G-minor Symphony and elsewhere, as shown by Schoenberg in his Harmonielehre (1911, 368). The dissonant neighbors also recall common features of African-American voice leading. According to Burton Peretti, stepwise voice leading has been common in African-American music since the nineteenth century. It was inherited from “African and Caribbean musical qualities such as pentatonic scales and melismatic sliding between notes” (2009, 25). The music thus combines classical phrase structure, pentatonicism, functional harmony, dissonance, and melismatic inner voice leading.

The consequent phrase enrichens the dissonance further. The dissonant dominant function is expanded into m. 13 and tonic only returns solidly at the end of m. 14. Measure 14 introduces functional mixtures that anticipate the polytonality of the second subject: the downbeat of the measure contains C♯7 (D) with an added E-natural in the melody, producing a combination of major and minor qualities. The dissonant second eighth note does not lead to a more consonant chord but to another dissonance: the diminished third {D♯, F} resolves implicitly to E, dovetailing with the resolution of {A♯, C} to B that follows, shown by the dashed lines in the example. The combination of a pentatonic melody with chromatic voice leading and dissonant harmony establishes the pluralistic nature of Still’s style.

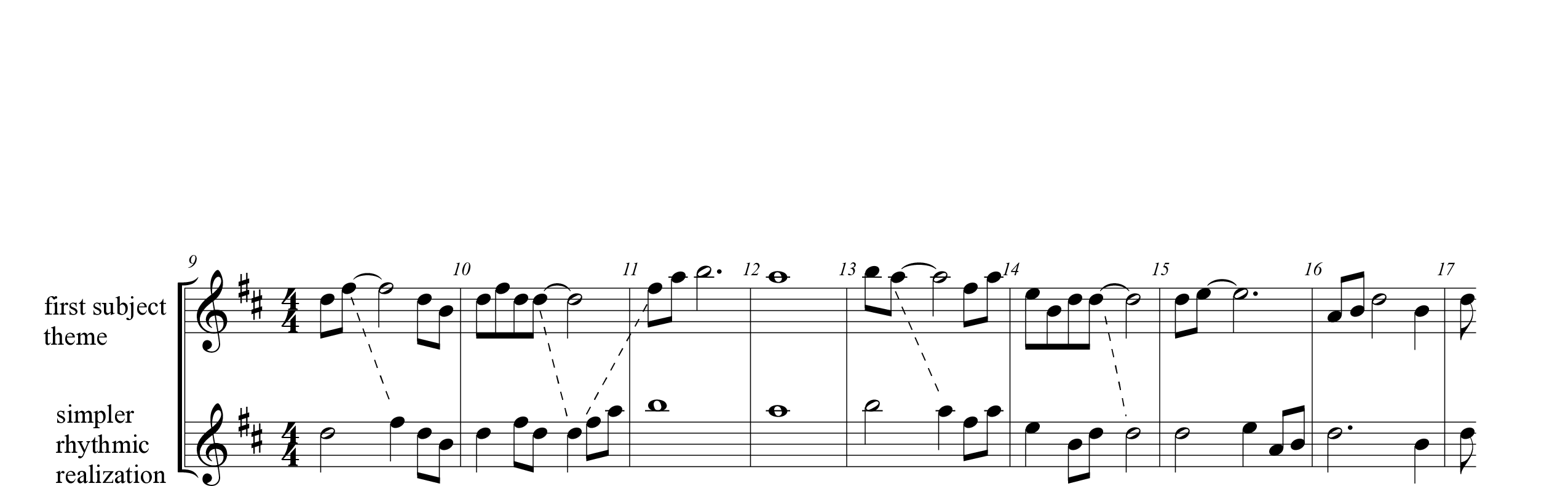

The first subject also combines the metrical squareness of the classical period with rousing syncopations associated with jazz. Example 4 provides a rhythmic analysis of the syncopations. The second eighth note in m. 9 enters “early” anticipating beat 2 of the measure and has the effect of a double syncopation since the stress given to beat 2 displaces the metrical accent by a beat and the eighth note anticipation itself displaces the stress. The second measure is a loose rhythmic retrograde of the first: half–quarter–eighth–eighth in m. 1 becomes eighth–eighth–quarter–half (where the half is shortened to a quarter to normalize the rhythm in m. 3) in m. 2. Measure 2 thus also contains two levels of rhythmic displacement, since beat 3 is stressed more than beat 1 and is also anticipated by an eighth note. My rather sterile recomposition illustrates how much interest the syncopation brings to the melody: the syncopation “signifies” what would otherwise be a hymn-like classical period.

One immediately noticeable quality of the piece is its perpetuum mobile of steady eighths, often supplied by the background winds. The movement’s steady rhythm—with its evocation of tireless industry, the steady flow of people and machines across the land—combines within it the syncopations of African-American music and the more rigid harmonic rhythm of European art music. There is nary a moment in the movement when some instrument is not chugging along, ensuring the piece’s forward momentum. Still’s use of African-American thematic and rhythmic materials in the service of European form might elicit worry or surprise if we accept this interpretation. Combined with the piece’s sunny, D-major disposition, the perpetuum mobile is undoubtedly meant to convey positivity belying the darker side of sprawling industry. But the upbeat, Time Forward!-like momentum of the piece must surely have been conscious: Still rejected both the aesthetics of avant-garde music and what he perceived to be the darker, confrontational role given to politics by some artists of his time. Discussing the role of politics in art, Still writes “In my humble opinion, politics as such should not enter into the consciousness of a true artist when his work is concerned. He should, however, be interested in the human problems that are a part of our lives, and should balance this with his interest in the abstract elements of his art form. It was the human need that impelled me to write such a composition as ‘In Memoriam: The Colored Soldiers Who Died for Democracy,’ rather than any political consideration, for whatever my political views or however I vote in the little curtained booth, these things have nothing whatever to do with the music I write” (Spencer 1992, 149). It could of course be argued, however, that Still’s music reflects the political context of his time, whether consciously or not. Still’s optimism stands in contrast to more pessimistic strains of thoughts current today, and though we might hear in Still’s music vestiges of oppression, he quite clearly intended his composition to look forward to a more universal harmony. I will consider the success of Still’s project in the conclusion below.

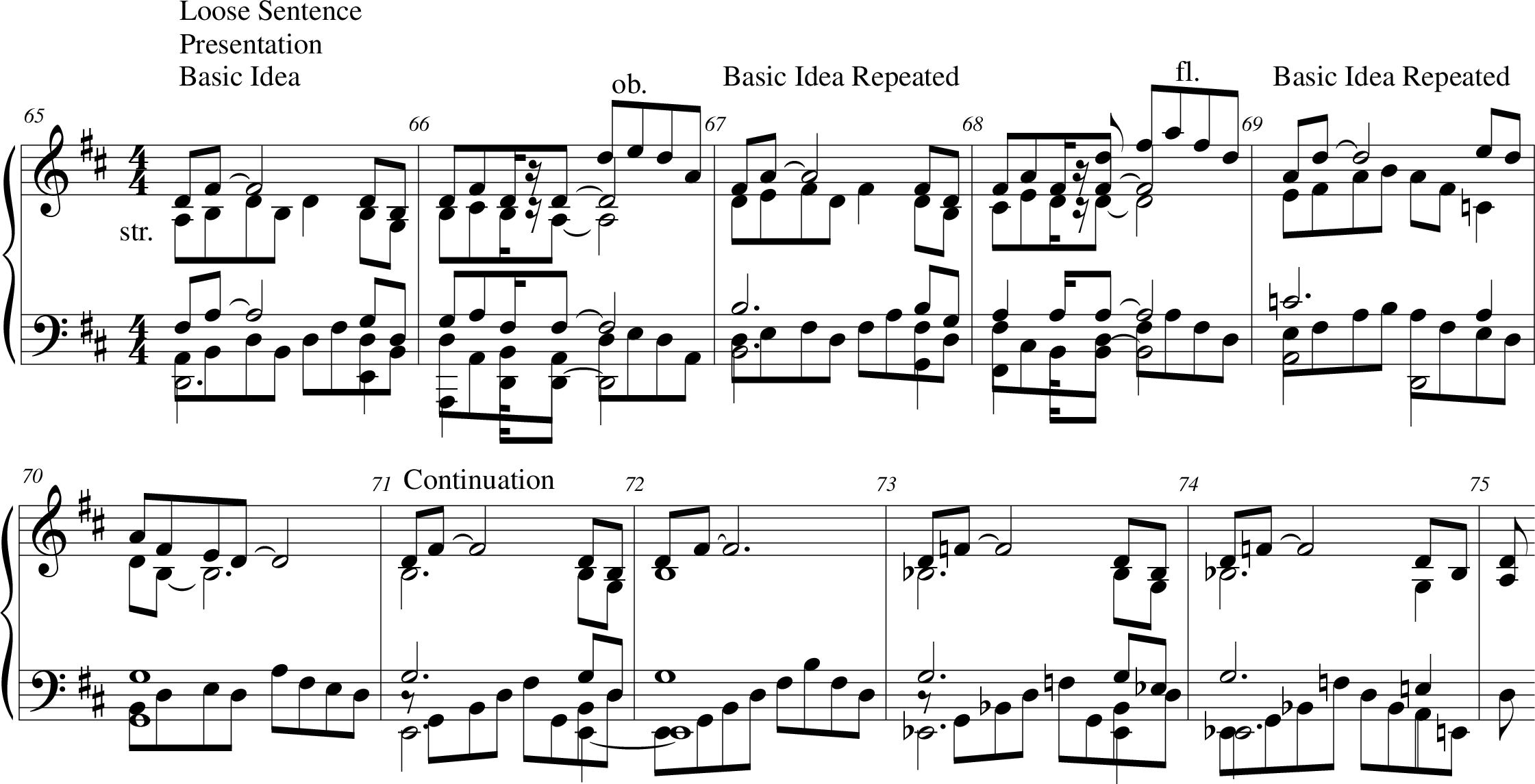

From the point of view of form, the first subject owes much to European art music. Its thematic conventionality, symmetry, limited thematic materials, and tonal stability make it what William Caplin (1998) calls “tight-knit.” Its formal stability will contrast with the instability of later thematic sections. The sole presence of strings imbues the passage with an intimacy and timbral homogeneity that effectively introduce the piece while leaving open the possibility for greater development and larger gestures to follow.

c) Second Subject

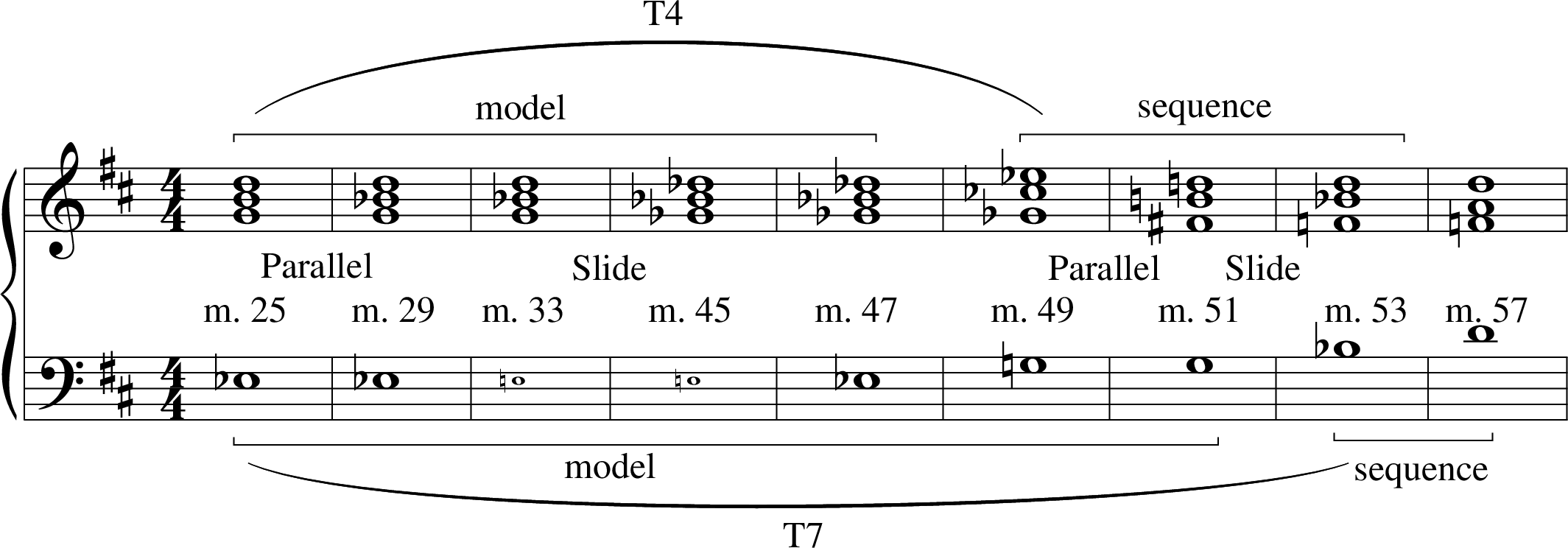

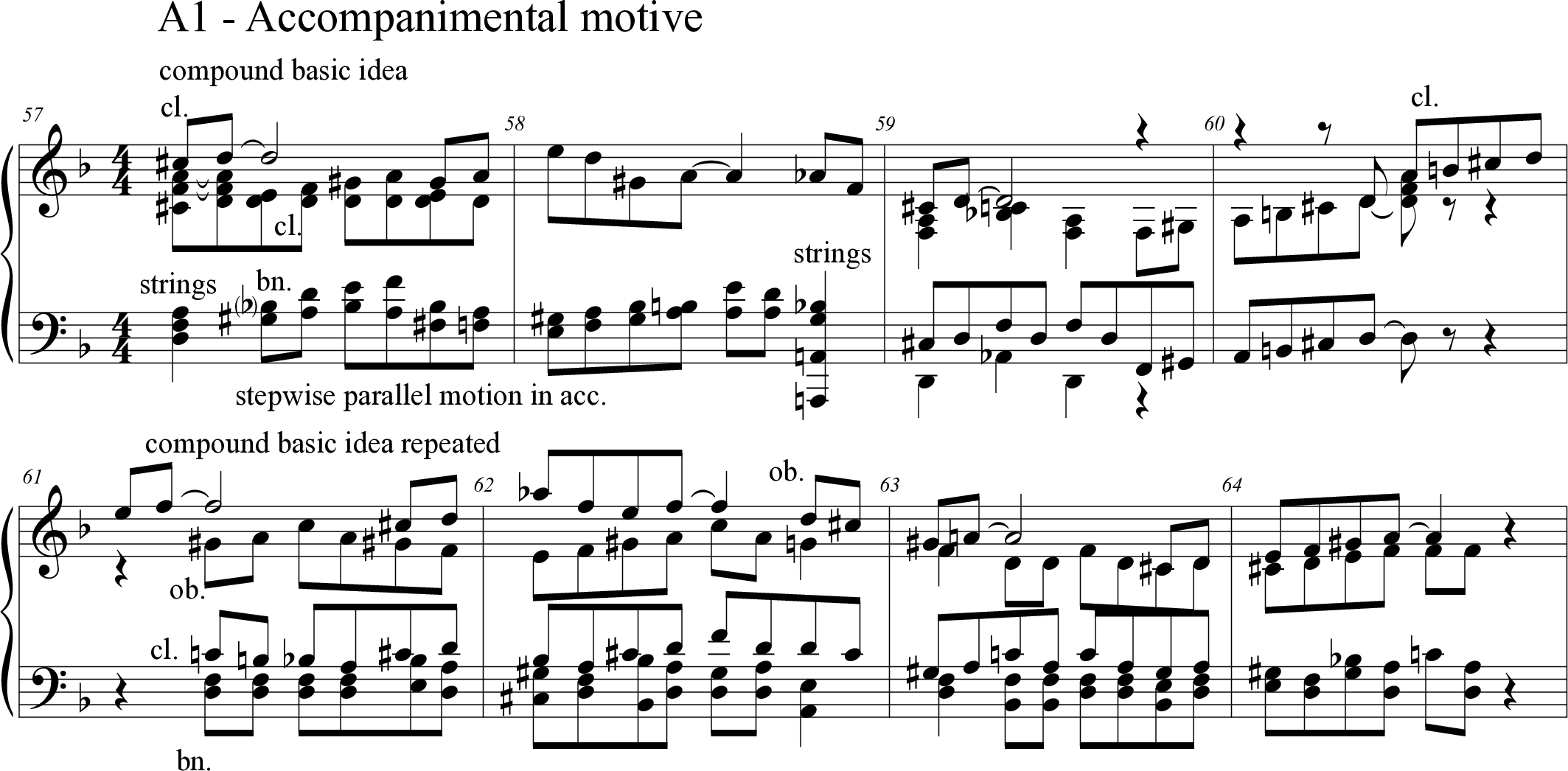

The second subject contrasts substantially with the first in its harmony, tonality, degree of formal stability, and orchestration. Example 5 provides a piano reduction of the second subject. The theme is an extended compound sentence, in keeping with the typically looser construction of second subjects. Still states the initial compound basic idea four times before fragmenting it and leading it to a final cadence in D minor. The theme is loosened by virtue of these repetitions, thematic extensions, and its auxiliary progression (since the theme lacks a convincing initial tonic or else modulates from E♭ to D). The cadence in the parallel mode of the home key is unusual, since the second subject normally brings tonal contrast, but the dissonant polytonal harmonies and the sequential underlying motion from G major and G minor over E♭ in mm. 25–32 to C♭ major and B minor over G in mm. 49–52 bring sufficient contrast to the exposition.

The entirety of the second subject is founded upon a major thirds sequence. Example 6 provides a brief transformational analysis of the second subject, emphasizing the sequential repetitions of the bassline motion and the chord progressions in the upper voices. The melodic chords outlined in the passage progress from G major in m. 25, to G minor in m. 29 (the neo-Riemannian “parallel” transformation), to G♭ major in m. 45 (the neo-Riemannian “slide” transformation). For more on these transformations, see Cohn 2012. While Riemannian and neo-Riemannian analysis rarely coexist, I have opted to include both here in order to illustrate how Still’s piece engages with different aesthetics simultaneously: the first subject is tonal-functional but includes the extended harmonies captured well by Riemannian functional theory, while the second subject draws on a sequential logic better described by transformational (or neo-Riemannian) analysis. For more on the distinction between the two approaches, see Rings 2011. In my analysis, the local transformations serve to expand the subdominant function, since in D major/minor, Eß, G, and B function as ^o^Sp, S^+^, and S^+^ of , respectively. The entire progression repeats under transformation T4 in mm. 49–53. The bass follows the upper voices by rising four semitones from E♭ in m. 25 to G in m. 49, preserving the dissonant, polytonal (0148) sonority: {E♭, G, B, D} becomes {G, C♭, E♭, G♭}. The bass’s large-scale motion depicted in Example 6 is supported by formal articulations: the first eight measures sustain Eß, the next two repetitions of the compound basic idea sustain E as an upper neighbor, and the continuation phrase reintroduces Eß in m. 47, initiating an increase in harmonic rhythm: G in mm. 49–52, Bß in 53–57, and the goal D in 58. Since m. 49 brings back the initial (0148) sonority, I hear the Eß–G motion as one unit. The Bß–D motion in the bass in mm. 53–58 has a transformational/motivic function, in that it repeats the earlier bass motion Eß–G, but it also forms part of a functional tonal cadence that ends the second subject, VI–ii–V–I in D minor. But the bass also contains its own T7 sequence: bass motion E♭–G in mm. 25–49 is then repeated B♭–D from mm. 53–57: a “composing-out” of the E♭ major seventh sonority sustained in mm. 29–32. The bass’s underlying T7 transformation is independent of the upper voices, reinforcing the polytonal textural dimension. On a large-scale tonal level, the progression serves to expand the subdominant function in D major/minor, but it also operates according to its own transformational or sequential logic. In contrast to the first subject, which was governed primarily by tonal-functional relationships, the second subject is more immediately concerned with a transformational logic common to many twentieth-century styles.

A reduction of the harmony in the first eight measures of the second subject is provided in Example 7. On a local level, the sonorities that arise throughout the passage are polytonal in that they are stratified registrally to form pairs of tertian sonorities and diatonic melodic fragments: G major against E♭ in m. 25, followed by F major against A♭ major on the downbeats of mm. 26 and 27, etc. The reduction provides a tonal functional analysis of the progressions in both keys and then sounding together: the result of the polyphonic combination is a succession of functional mixtures in the key of E♭ major, though since G major sounds prominently above, one might also hear the progression primarily in G. The harmonic logic of the passage is largely linear in that the specific verticalities result from combination of melodic lines: the contour of the soprano’s melody in mm. 25–27 (D–C–D–C–A–C–D) is inverted by the bass (E♭–A♭–E♭–A♭–C♭–A♭–E♭). The soprano line is the chordal fifth of a series of parallel major triads, while the bass line supports a series of parallel perfect fifths. Together, the harmonic sonority is dissonant.

Overall, the passage tends toward consonance as illustrated by the chords’ interval vectors. Each four-measure phrase is bookended by chords with prominent thirds and fifths. Intermediary chords contain higher numbers of semitones, whole tones, and tritones. The change in mm. 29–32 from G major to G minor in the upper voices reduces the number of semitones and increases the prominence of fifths. Later portions of the second subject mostly contain conventional seventh chords: the sustained E half-diminished seventh chord in mm. 33–44, the G♭ dominant seventh chord in mm. 45–48, etc. But the striking cross-relation of G/G♭ in mm. 49–52 and the major chords in m. 50 that lie a semitone away from each other—D against D♭ in m. 50.2 and B against B♭ in m. 50.4—restore the earlier dissonances heard at the beginning of the second subject.

Still structures the second subject around numerous logics: tonal functions, sequential repetitions (transformations), progression from intervallic dissonance to consonance, and loose melodic inversion. The combination of structuring principles reflects multiple musical influences: the planing of African practice, the polytonality and inversional relationships of modernist styles, and the tonal prolongation of the subdominant in D minor. But since the passage ends in the global tonic’s parallel minor, it is marked as unsatisfactory; it is as if the idealized, autochthonous music Still is grasping for will require further dissection and reassembly before it achieves the right proportions, and where better to experiment than in the development?

d) Development

The development section is formally complex: it separates and recombines material in a way typical of classical developments but also bears the extra meaning resulting from Still’s pluralistic combination of styles. The form chart in Example 1 documents what James Hepokoski and Warren Darcy (2006, 611) describe as a “rotational structure,” which “extend[s] through musical space by recycling one or more times—with appropriate alterations and adjustments—a referential thematic pattern established as an ordered succession at the piece’s outset”—in this case, the development’s outset. Sections labeled A, which contain motivic fragments drawn from the second subject, alternate with those labeled B, which contain reworkings of the first subject’s theme. While the A sections remain mostly in D major/minor, the B sections explore key areas remote from the global tonic, including C♯ minor and G♯ minor. The A sections also have a preparatory character because they contain short fragments that precede fuller statements of thematic material more completely drawn from the exposition.

Examples 8 and 9 provide piano reductions of the A sections, and Examples 10, 11, and 12 provide piano reductions of the B sections. The A sections are unified through the emphasis on a new recurring, bustling accompanimental figure that often outlines a half-diminished seventh chord. Gradually, the A sections introduce more new rhythmic figures that are motivically related to the opening motto, including new syncopations and diminutions of the motto in sixteenth notes. The B sections recast the first subject in the minor mode while fragmenting and reworking it harmonically. As the music progresses, it becomes darker, thicker, and more dissonant until a D-minor climax recedes and prepares the onset of the recapitulation with a dominant.

A Sections

The A sections gradually become more complex. The first rotation, provided in Example 8, contains an eight-measure compound basic idea followed by another compound basic idea. This passage draws primarily on a new scale related to the common blues scales, D–E–F–G♯/A♭ –A–B♭–C♯, whose tritone G♯ above the tonic introduces a dissonance that will characterize the darker development section as a whole and which will be developed in further rotations of the A sections (see below). Blues scales typically feature scale-degree ƒ4/ß5 in addition to a minor third above the tonic. For more on blues scales see Chodos 2018, which summarizes different theoretical approaches to the blues scale and questions its validity as a theoretical construct. Most theories of the scale include \^ß3, \^∂3, \^ƒ4, \^ß7, and \^∂7 without \^ß6. In the passage cited, Still combines the sound of the blue scale with passages that correspond more closely to the minor mode, for example the inclusion of \^ß6 and short melodic-minor scale-fragments, A–B–Cƒ–D. Harmonies arise from the mostly stepwise parallel motion of multiple voices through the scale, though oblique motion against a repeated D pedal arise frequently, too. It is interesting that Still contrasts a blues-like scale in the development section with the more diatonic and major-pentatonic scales of the exposition. The blues scale, long considered to be a mixture of received African scales and Western diatonic scales, provides both a new color but also evokes, perhaps, a potential musical problem that will require resolution in the recapitulation and coda: how to balance and blend European and African traditions. Paul Oliver (1991) also charts the history of the blues and of pioneering musicological studies of it by Rudi Blesh, Gunther Schuller and others. One common thread among the many different theories provided for the origin of blues is its combination of African and European elements, though historians disagree about its relationship to jazz, when and where it originated, etc.

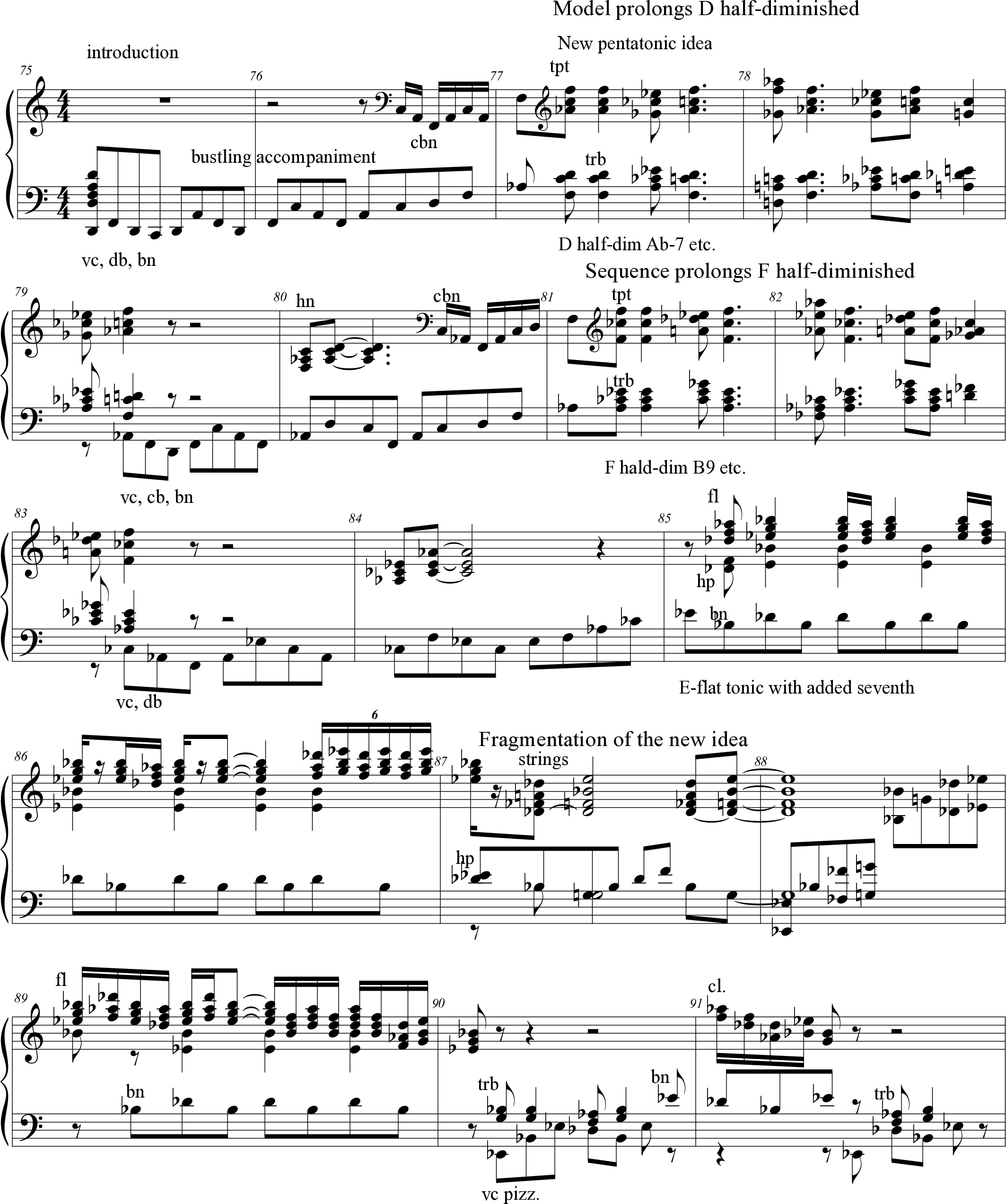

The second rotation of the A section, provided in Example 9, contains the same bustling accompaniment but introduces a new syncopated idea in mm. 77–79 derived from the F minor pentatonic collection. The passage is then harmonically sequenced up a minor third in mm. 81–83, contributing to a mild core-like effect. The music then fragments the idea while sustaining an E♭-dominant seventh chord that at first sounds like a tonic with a lowered seventh before it functions as the enharmonic dominant in G♯ minor, which arrives in the following passage (rotation B2). One of the more distinctive features of the passage is the alternation of different instrumental families: low strings in mm. 75–76, brass with pizzicato strings in mm. 77–84, winds and harp in mm. 85–86, strings in mm. 87–88, and so on. The avoidance of doublings between families produces a thinner sound but also differentiates the development from the exposition: the spotlight thrown onto the different families mirrors the intensified application of one of the three stylistic elements—the bluesy quality of rotation A1 compared to the more modernist dissonances in A2, etc. The development section isolates these elements slightly before allowing them to join together in the recapitulation and coda (see below).

B Sections

The B sections draw primarily on first-subject material, but instead of presenting the entirety of the theme’s period, the B sections fragment the theme. The first rotation of the B section, B1, is provided in Example 10. Still transforms the subject from a period into an extended sentence, loosening the structure—a relatively simple alteration that prepares the more complex ones to follow.

Example 11 provides the second rotation of the B section, B2, which contains five layers: the first violins, the violas, the bassoon, the cellos, and the trombones and tubas. In the first layer, the violins play fragments from the first subject with the syncopations discussed above, resulting in one of the piece’s few grouping dissonances in mm. 103–104. The four-eighth-note figure in m. 103 is repeated but extended by two eighths into m. 104, after which it fragments into two three-eighth units. The additive and subtractive rhythm contributes to the developmental nature of the passage: Still plays with the lengths of the theme’s units departing from the exposition’s consistent four-measure phrasing. The chordal attacks in the brass emphasize the beat while the violas emphasize the third and sixth eighths of the measure and the bassoons occasionally enter to emphasize beat 2. More subtly, the cello’s low G♯s in the first six measures provide a hint of syncopation since, as the lowest pitches of their line, they do not occur on strong metrical positions. The sophisticated layering of different ostinati creates a complex rhythmic fabric that recalls the circular cross-rhythms of sub-Saharan music and its influence on American music. See, for instance, the rhythmic-set structure of sub-Saharan drumming in Anku (2000) and Kubik (1994). Layered ostinati are common to many different African cultures.

Still combines melodic features of the first subject with harmonic features of the second in rotation B2. The first subject’s theme returns recognizably in the minor mode, but the accompaniment punctuates it with new harmonic support. In mm. 97–98, Still introduces whole-tone chords on beat 4 that function locally as D of D (a varied augmented sixth chord). The basslines in these two measures, with its emphasis on G♯–E–C, recalls the T4 transformations of the second subject. Still intensifies the harmonic dissonance in mm. 100–102: an F-major chord follows the G♯-minor chord in m.100, and a D-major-seventh chord follows the G♯-minor chord in mm.101–102. The bassline motion now outlines a loose T3 progression, G♯–F–D, and the tritone, G♯–D, will come to have a growing role in the development that follows. The combination of these materials serves to problematize the first subject material: will the first subject withstand the dissonances and sequences of the second subject, and can the two subjects coexist?

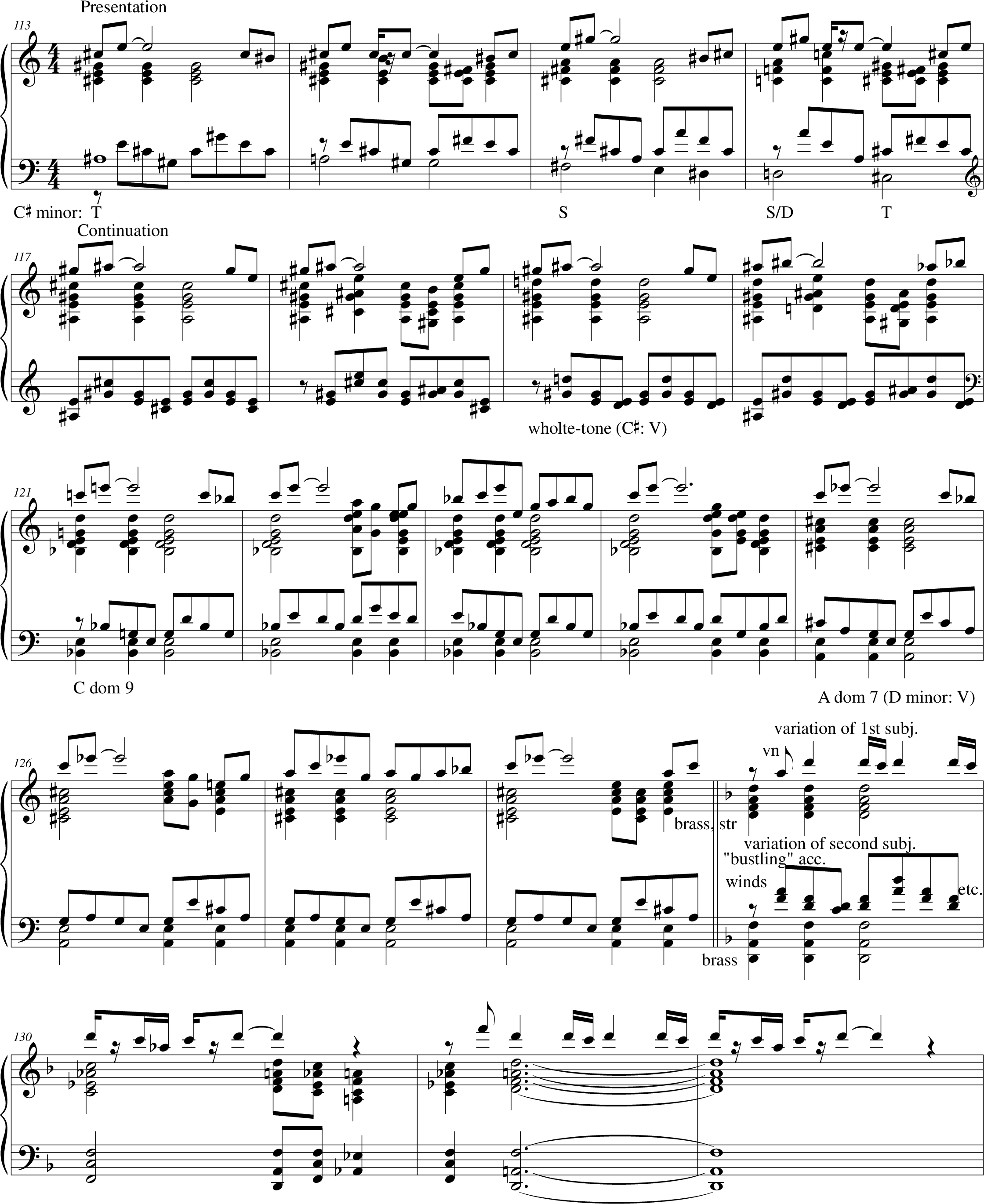

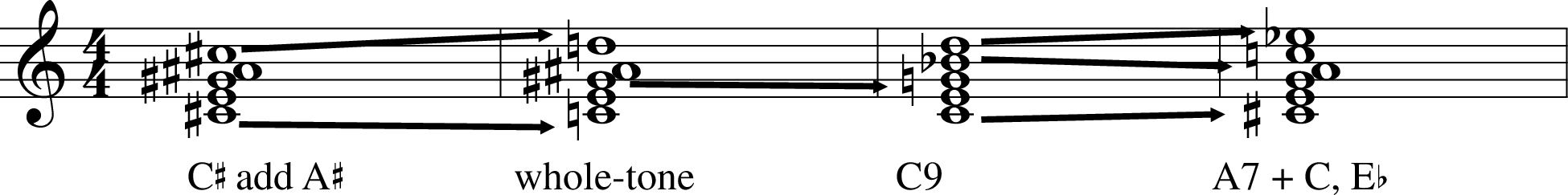

The third rotation of the development’s B section, provided in Example 12, includes some of the most dissonant harmony and extended process of fragmentation in the whole movement. After the initial statement of the first subject’s presentation in C♯ minor in mm. 113–116, to which a lament-bass-like countermelody is added in the cellos, Still fragments the theme’s basic idea for twelve measures. The continuation phrase passes from a C♯-minor chord with added A♯, {C♯, E, G♯, A♯}, to a whole-tone chord, {B♯/C, E, G♯, A♯, D}, to a C-dominant-ninth chord, {C, E, G, B♭, D}, to a combination of A-dominant-seventh chord with added C and E♭ in the violins, {C♯, E, G, A, C, E♭}—which could be read as a combination of A7 and A half-diminished, or A♯9♭5, a chord common to the world of jazz. Example 13 provides a reduction of the harmony in the continuation phrase. The gradual semitone voice leading indicated by the solid arrows echoes at a much slower pace the semitone voice leading of the harmony in the first subject. While in the first subject, the chromatic voice leading ultimately supported a functional progression in D major, in the development, the passage serves to modulate from C♯ minor to D minor and culminates in a sustained, dissonant sonority.

The development’s climax in mm. 129–136 combine the first and second subject together with the bustling eighth note figure that characterizes the A rotations of the development. The contrapuntal sophistication of the passages contrasts with the breezier homophony of the exposition. The harmonic motion is also non-diatonic, moving from a D-minor chord in m. 129 to an F-minor-seventh chord in m. 130, to a combination of A♭ and F-major chords on beat 4 of the same measure. Taken all together the themes returning in the minor mode, the non-diatonic harmony, the presence of the tritone melodically and in the dissonant combination of F major with A♭ major, and the thick, loud tutti-like texture establish the passage as the problematic crux of the movement that the recapitulation will solve. Similar crises may be found in passages from major nineteenth-century symphonies. Famous examples include dissonant minor-mode passages in the third movement of Bruckner’s Ninth Symphony, the first movement of Mahler’s Tenth Symphony, the finales of Beethoven’s Eighth and Ninth Symphonies among others. The “negative climax” in Still’s Fourth is perhaps less dramatic and extreme than some of these examples, but the effect is similar.

The development section as a whole is unified not just through the presence of repeating accompaniment figures and expository materials, but also through the tritone, both as an interval within a chord and as a melodic interval. The discordant interval makes increasing appearances with each rotation of the A section. Its initial appearance in the bassline in m. 59 (Example 8) is dwarfed by its emphasis in the half-diminished chords in mm. 77–79 (Example 9) that move by minor third, D half-diminished to F half-diminished, and in the bustling accompaniment figures in the lower instruments in the measures that follow: A♭–F–D, etc., which outlines a tritone. In m. 87, juxtapositions of chords separated by tritone when respelled first appear: {A, C♯, E} with added B♭ resolves to {E♭, G, B♭, D♭, F}. At first, the two chords function as dominant of the B section’s G♯ minor in m. 97 (Example 11), but when the combination of an A-major chord with the pitch E♭ reappears in mm. 125–128, the chord functions as dominant of the next B rotation’s D minor tonality, beginning in m. 129. The tonal scheme of the development section itself thus follows a tritone transposition: it begins in D minor in mm. 57–65, proceeds to G♯ minor in mm. 97–104, and culminates with D minor in mm. 129–144: a loose “composing-out” of the D–G♯ tritone introduced in the development’s allusion to the blues scale. Once the climactic section begins in m. 129, local progressions with roots separated by a tritone come to dominate the harmony: D minor to A♭ major and back in m. 129 (the progression is repeated several times); D♭ major seventh to G dominant seventh in m. 139; D minor to A♭ major with added sixth in m. 142, etc. The dissonances produced by the progressions and superimpositions recall and develop the polytonal combinations of the second subject while also introducing an element of conflict common to the rhetoric of the classical development section.

e) Recapitulation

The recapitulation synthesizes the contradictions of the development section. Still achieves an optimistic synthesis by combining the elements together harmoniously and by limiting the scope of the dissonance found in the exposition and development. The first subject eschews the semitone voice leading of the exposition, and the melody is given to the flute with rich doublings and countermelodies in the winds and strings followed by a second statement in the strings with accompaniment in the strings, harp, and celesta. The short transition from mm. 169–174 re-introduces chord progressions by tritone and minor third: D major alternates with F minor and F major in quick succession.

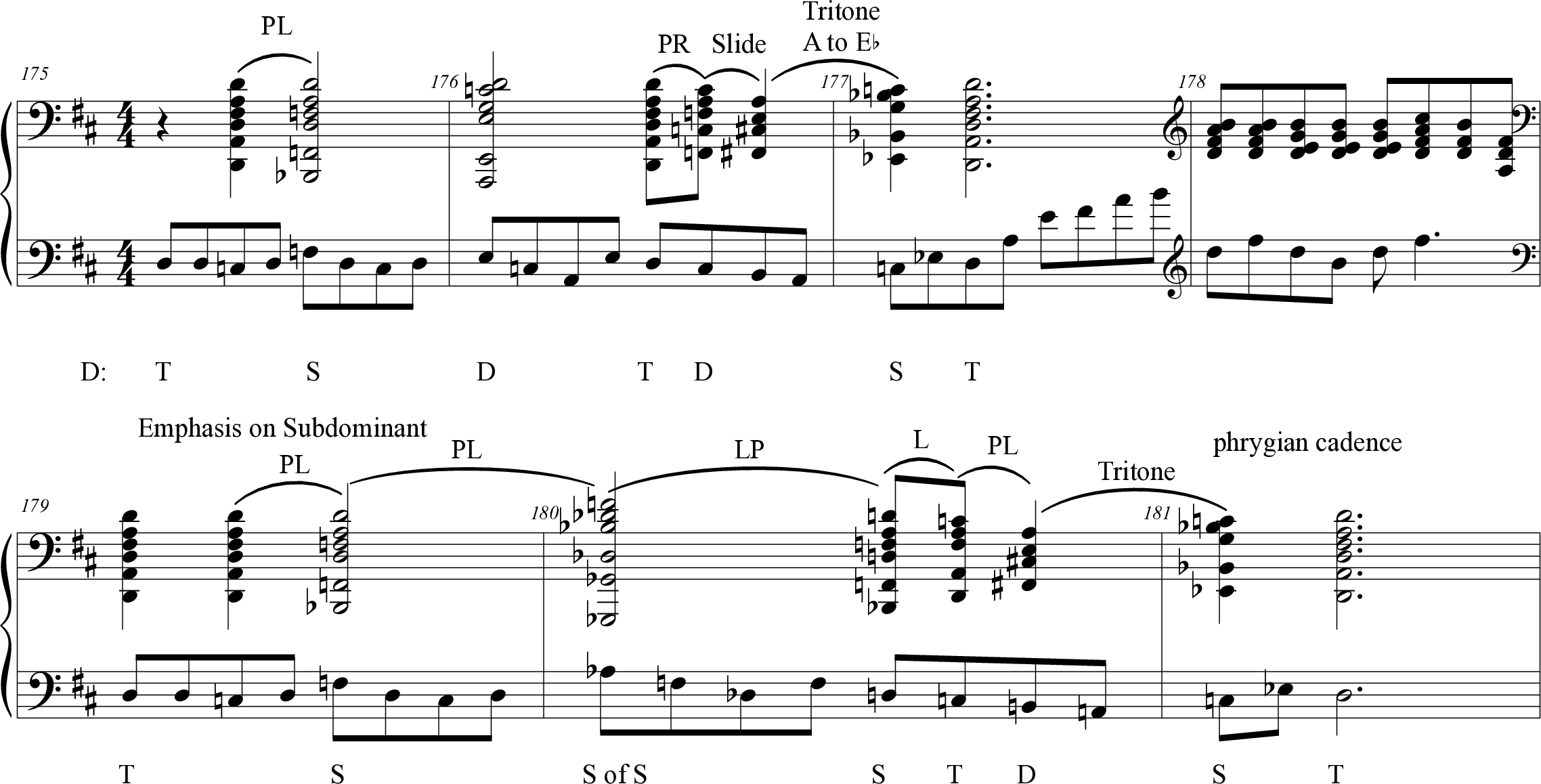

Example 14 provides a reduction of the recapitulation of the second subject. Still synthesizes harmonic elements from the exposition’s first and second subjects and from the development. The passage is in the key of D major, the global tonic. Its harmonies function tonally within D major, but extra weight is given to the subdominant—a common feature of recapitulations and codas in sonata form—by including Phrygian cadences and an emphasis on the flat side of D major: ♭VI, ♭III, and ♭II. The chord progressions also recall the movement by third that characterized the harmony of the second subject in the exposition. Finally, the progression F♯-minor seventh to C-minor seventh in mm. 2 and 3 and again in mm. 6 and 7 show the influence of the tritone progression that came to dominate the development section. By bringing each element—the global tonic, the non-functional triadic progressions, and the tritone—into a cohesive whole, Still provides a nearly conclusive solution to the problem posed by their conflict earlier in the piece. Still reserves the final, incontrovertible cadence for the coda.

f) Coda

The coda, as shown in Example 15, resolves many of the conflicting stylistic impulses established earlier in the piece left unresolved by the recapitulation: the conflict between diatonic and chromatic harmony, rhythmic stability and syncopation, and orchestral stratification and blending. A final I–vi–IV–ii–V–I progression solidifies the D-major tonic and recalls Caplin’s (2021) “iconic cadence”—a tonally normative and rhetorically emphasized cadence that sometimes ironically evokes the definitiveness of cadences from earlier repertories in late-romantic and early modern music in which such cadences more rarely arise. (I will return to the discussion of this cadence in the next section.) The bass in mm. 183–190 moves entirely on the beat, and the harmonic rhythm quickens in mm. 187–188. The brass instruments, which had been emphasizing beats 2 and 3, liquidate to a simpler, steady quarter note pulse in mm. 188–189. The violins similarly cease their syncopated quarters in m. 189. The ensemble has seemingly liquidated to steady eighths and quarters in the final measure, but the piece surprisingly ends on the weak fourth quarter of the measure, and the violins play one last syncopated rhythm, evoking the first subject. Like the second subject, which combined harmonic elements from the piece’s different sections and stylistic sources, the coda smooths out the syncopations in order to signal the approaching formal closure, but it ultimately gives syncopation the last, triumphant word. The dissonances and polytonality of the second subject are here erased, and the forward march of the glorious, ringing D major sweeps past any objections raised by earlier problems.

Hermeneutics and Concluding Remarks

It is a testament to Still’s considerable imagination that he so effortlessly combines musical styles and aesthetics seemingly at odds with one another. Though the Fourth Symphony prizes simplicity, it is by no means simplistic: the above analysis highlights the minute details of the work and demonstrates how Still creates local and large-scale contrasts in a variety of musical domains in order to construct its meaning. The atmosphere is one of infectious optimism that unifies diverse styles and approaches in a pluralistic whole: tonal function combined with polytonality and pentatonicism; diatonicism with unconventional chromaticism; classical phrase structure with jazz rhythms; the dialectics of sonata form with the immutable perpetuum mobile and ostinato.

But does the music (too) successfully fuse and anneal, like pieces of scrap metal into a strengthened whole, diverse musical styles? Is this music truly “autochthonous”? While Still does include modernist and African-American elements in the symphony, it is clearly weighted in favor of European art-music practices. Smith argues that “Still composed (for whatever reason) conservative, less dissonant music and was himself politically conservative.” (2000, 200). One might question the degree of the piece’s conservatism, however. Compared to Varèse, Schoenberg, or Ives, Still’s music clearly retains more harmonic and formal features typical of the common-practice period. But Still’s music also contributed to a return to simplicity that defined not only much American music of the time, but art as well—for instance, the Urban and Social Realists of the 1930s who similarly spurned avant-garde developments in favor of portraying the complexities of American rural and urban life. Aaron Copland’s “imposed simplicity” defined his output in the 1930s and early ’40s (Crist 2005) and Virgil Thomson, whose return to simplicity in the 1930s coincided with a greater interest in African-American music making. Like Still’s symphony, Lisa Barg describes Thomson’s opera Four Saints as “a beguiling map of sonic memories, a cartography of musical styles encompassing the old and new, vernacular and cultivated, sacred and secular.” (2000, 126). In addition to its combination of “Baptist hymns, parlor dances, and sentimental ballads . . . drinking songs, marches, fanfares, and operetta,” the opera also includes portrayals of African-American music. The complexity of racialization in Thomson’s work is fraught but underscores a growing awareness of the centrality of Black contributions to American musical culture. A poet friend of Thomson’s “liken[ed] the effect of Thomson’s music to the healing power of sunlight on the skin, restoring color back to the lifeless pallor of a European musical body ravaged by the bloodless scourge of (Germanic?) modernist dissonance.” (Barg 2000, 125). Whatever one might think of such an appraisal, it does resonate with Still’s similar rejection of some of the most stringent aspects of modernism as learned during his study with Varèse and with his desire to reintroduce to art music a simplicity tinged with African-American (musical) experience. By the mid-1940s, however, the simpler American style was changing. Composers whose music belonged squarely to the tonal-symphonic tradition began increasingly to include new compositional devices. Roger Sessions’s Second Symphony of 1947 retains the galloping forward momentum of his earlier music, but ladens it with dissonances and hints of his use of the twelve-tone technique to come. Howard Hanson’s Fourth Symphony of 1943 —a requiem with modal materials that recall earlier European music more than living American folk styles—contains diatonic passages of romantic splendor alongside intense, dissonant climaxes. Samuel Barber’s Second Symphony of 1944 makes use of an electronic tone generator. In this context, Still’s symphony and the solutions his music provides to the problems it establishes seem perhaps conventional or backward-looking.

Jacqueline DjeDje argues that while the overall aesthetic of the symphony was conservative for 1947, Still’s “fusion of both the neoromantic and modernist styles…[reflects] his desire to integrate the idioms of other cultures to create a ‘universal’” (2011, 20). Djedje compares Still’s desire for universality to Cynthia Kimberlin and Akin Euba’s concept of “intercultural music,” which Djedje defines as music whose “composers, regardless of their ethnic or cultural origin, integrate elements from two or more cultures” (2). She argues that

In the midst of Los Angeles’s population shifts and ethnic tensions, caused in part by restrictive covenants and the economic activity surrounding World War II, Still’s use of intercultural elements in the forties and later was prophetic and significant because this may have been his way of proposing solutions to social problems. By embracing and integrating musical elements of different ethnic groups (Africans, African Americans, American Indians, Latinos), Still was calling for interhuman understanding. (2011, 21)

Many of Still’s most universalist pieces would follow the Fourth Symphony: DjeDje lists Carmela (1949), Four Indigenous Portraits (1956) and Minorities and Majorities (1971) as pieces that make especial use of pluralist materials. In the Fourth Symphony itself, the interpenetration of different styles is deep and sincere: there are no token or stereotypical evocations of folk or jazz idioms in Still’s symphony, rather elements from these sources form part of the symphony’s structure and its manipulation of the material. Passages are imbued with combinations of elements: syncopation, tonal-functional harmony, displacements of chords by semitone, and polytonality. Still attempts to resolve the conflict between autochthony and universalism by appealing musically to the mythical American “melting pot,” in which diverse experiences and backgrounds fuse into a new alloy. In the Fourth Symphony, classical form and phrase structure, tonality, polytonality, freer dissonance handling, harmonic parallelism, jazz rhythm and harmony, and pentatonicism—a musical pluralism that aims at universality—combine together in a specifically American way: American pluralism as autochthony.

The result, though, remains somehow sanitized: Still’s solution to the diverse compositional styles that sometimes uncomfortably rub elbows in the exposition and development is to provide a mostly diatonic recapitulation and a gigantic, affirmative ii–V–I cadence at the end of the symphony. The polytonality and rhythmic dissonances explored in the second subject and development section are treated as problems, since they lead to the enormous D-minor climax and are subsequently restrained in the recapitulation, except for brief nods. Still’s symphonic movement addresses modernist techniques but, like a microcosm of his own career, ultimately rejects them. In so doing, Still seems to suggest that a euphonious synthesis of the diversity of music and social experience in the modern world can only be achieved in the idealized realm of the imagination. In order to create his style, Still relegates the discords—not just of musical modernism, but of the chaotic, embattled, at times anarchic world modernism seeks to represent—to a less prominent position in the piece’s structural hierarchy. And the music of other American cultures—both transplanted and genuinely native—are conspicuously absent. The symphony’s scope is too narrow to be truly universal, and yet too far removed from the musical roots of any one tradition to be autochthonous.

Viewed in this way, Still’s symphony is not a vision of the world or of America as it is, but as he imagined it to be. If his quest was to produce a “universal” music, or a universally accessible American music, I believe he failed. But if we discard the utopian idealism and consider the music’s technical achievements and compositional subtlety, the symphony reveals itself to be, beyond well-crafted, a highly individual work and one that is genuinely “autochthonous,” in that it could only have evolved from the catalysis instigated by the mixture of numerous American influences and the personal expression of Still’s unique compositional genius.

For much more on the socio-political and musical motivations for Still’s move to Los Angeles, see DjeDje 2000. Still was likely motivated to move there because of growing disillusionment with musical life in New York and because of the high concentration of diverse and talented musicians working in Hollywood. At the time, however, it was still a risky adventure, and so the echoes of Greeley’s famous advice, “Go west, young man,” despite Still’s more advanced age, are impossible to ignore. : For much more on the socio-political and musical motivations for Still’s move to Los Angeles, see DjeDje 2000. Still was likely motivated to move there because of growing disillusionment with musical life in New York and because of the high concentration of diverse and talented musicians working in Hollywood. At the time, however, it was still a risky adventure, and so the echoes of Greeley’s famous advice, “Go west, young man,” despite Still’s more advanced age, are impossible to ignore.

The word “autochthonous” comes to us from Ancient Greece where it applied to the indigenous inhabitants of a territory as opposed to colonists or settlers and their descendants—autochthonous individuals are products of the soil itself. Still’s use of the term suggests a metaphorical autochthony as opposed to a literal one, since, while he alludes to the truly autochthonous music of American aboriginals, his artistic vision combines it with the music of the descendants of colonists, immigrants, and slaves. While “autochthony” also had darker, proto-nationalistic connotations, it is clear that Still intends for the word to connote inclusivity and pluralism. For more on the term and its Athenian roots, see Blok 2009. : The word “autochthonous” comes to us from Ancient Greece where it applied to the indigenous inhabitants of a territory as opposed to colonists or settlers and their descendants—autochthonous individuals are products of the soil itself. Still’s use of the term suggests a metaphorical autochthony as opposed to a literal one, since, while he alludes to the truly autochthonous music of American aboriginals, his artistic vision combines it with the music of the descendants of colonists, immigrants, and slaves. While “autochthony” also had darker, proto-nationalistic connotations, it is clear that Still intends for the word to connote inclusivity and pluralism. For more on the term and its Athenian roots, see Blok 2009.

Haas describes the movement as being formally “free” while alluding to sonata-allegro form (1987, 43) and somewhat mystifyingly claims that the piece proceeds from D major to C major to D major. I believe the piece adheres rather closely to sonata form. Still himself wrote that while sketching a new piece “my usual practice is to map out a plan which conforms loosely to the established rules of musical form, and then deviate from it as I see fit.” (1987a, 109). His statement implies that he uses sonata form as a generic backdrop for his music despite superficial deviations from established norms. : Haas describes the movement as being formally “free” while alluding to sonata-allegro form (1987, 43) and somewhat mystifyingly claims that the piece proceeds from D major to C major to D major. I believe the piece adheres rather closely to sonata form. Still himself wrote that while sketching a new piece “my usual practice is to map out a plan which conforms loosely to the established rules of musical form, and then deviate from it as I see fit.” (1987a, 109). His statement implies that he uses sonata form as a generic backdrop for his music despite superficial deviations from established norms.

For more on organicism in music and its relationship to philosophy and the arts, see Solie 1980 and Neubauer 2009. While organicism is frequently described in Western philosophical terms—where it begins with Aristotle, passes through German romanticism to Spengler, and continues to influence contemporary thought—what Thorsten Botz-Bornstein describes as “micro-macro” thought is common also to non-Western culture. Botz-Bornstein interprets organicist thought in Chinese, Japanese, Russian, Arab, and Bantu cultures: the Bantu concept of ugumwe—roughly, “oneness”—denotes a political, collective solidarity between members of families, clans, and tribes (127). : For more on organicism in music and its relationship to philosophy and the arts, see Solie 1980 and Neubauer 2009. While organicism is frequently described in Western philosophical terms—where it begins with Aristotle, passes through German romanticism to Spengler, and continues to influence contemporary thought—what Thorsten Botz-Bornstein describes as “micro-macro” thought is common also to non-Western culture. Botz-Bornstein interprets organicist thought in Chinese, Japanese, Russian, Arab, and Bantu cultures: the Bantu concept of ugumwe—roughly, “oneness”—denotes a political, collective solidarity between members of families, clans, and tribes (127).

My approach to thematic transformation is indebted to Rudolph Reti’s (1951) method in which the motives comprising a larger theme may be freely rearranged (“interverted”) and varied. Reti contends that thematic transformations and relationships of this sort are central to the aesthetics of post-Beethovenian organic form, in which small motives mutate and grow across a work—a thematic conception eerily similar to Still’s own above. Solie (1980) argues that Reti’s method exemplifies organicist conceptualization and analysis of music. More recent motivic theories similarly consider permutation and more distant motivic relationships; see for example Auerbach 2021. : My approach to thematic transformation is indebted to Rudolph Reti’s (1951) method in which the motives comprising a larger theme may be freely rearranged (“interverted”) and varied. Reti contends that thematic transformations and relationships of this sort are central to the aesthetics of post-Beethovenian organic form, in which small motives mutate and grow across a work—a thematic conception eerily similar to Still’s own above. Solie (1980) argues that Reti’s method exemplifies organicist conceptualization and analysis of music. More recent motivic theories similarly consider permutation and more distant motivic relationships; see for example Auerbach 2021.

The pentatonic collection can also be found in other American music from the first half of the twentieth century, for example in the music of Aaron Copland, see Heertderks (2011). The music likely borrows from or alludes to African contributions to American music. : The pentatonic collection can also be found in other American music from the first half of the twentieth century, for example in the music of Aaron Copland, see Heertderks (2011). The music likely borrows from or alludes to African contributions to American music.

See for instance Kubik’s discussion of the Gogo tone system which includes at least seven pitches corresponding closely to the harmonic series (1994, 179) as well as hexatonic and heptatonic scales found in Cameroon, Angola, and Zambia (1994, 174). : See for instance Kubik’s discussion of the Gogo tone system which includes at least seven pitches corresponding closely to the harmonic series (1994, 179) as well as hexatonic and heptatonic scales found in Cameroon, Angola, and Zambia (1994, 174).

David Temperley has noted that syncopations, especially anticipatory ones, are commonly found in late 19^th^-century ragtime music and in recordings made contemporaneously by African-American singers (2021). Kubik (1994) similarly traces syncopation practices in a wide variety of sub-Saharan African cultures. : David Temperley has noted that syncopations, especially anticipatory ones, are commonly found in late 19^th^-century ragtime music and in recordings made contemporaneously by African-American singers (2021). Kubik (1994) similarly traces syncopation practices in a wide variety of sub-Saharan African cultures.