I am grateful to Mark Anson-Cartwright, Loretta Terrigno, and Allan W. Atlas for comments and insights that strengthened every draft of this article. When Mozart wrote to his father on September 26, 1781, about the composition of Die Entführung aus dem Serail, he could hardly have known that his letter would rouse so much interest among readers other than its addressee. And he might have been pleased at the fuss we have made, centuries later, over his proud justification of the unconventional second coda in Osmin’s first-act aria, “Solche hergelauf’ne Laffen”:

[A]s Osmin’s rage gradually increases, there comes (just when the aria seems to be at an end) the allegro assai, which is in a totally different meter and in a different key; this is bound to be very effective. For just as a man in such a towering rage oversteps all the bounds of order, moderation, and propriety and completely forgets himself, so must the music too forget itself. But since passions must never offend the ear, but must please the listener, or in other words never cease to be music, so I have not chosen [for the second coda] a key foreign to F (in which the aria is written) but one related to it—not the nearest, D minor, but the more remote A minor.

Mozart knew that “Solche hergelauf’ne Laffen” presented a highly individual and dramatically sensitive musical characterization while remaining coherent within the harmonic-structural syntax of late-eighteenth-century music. He also seems to have known that he really “outdid” himself with the portrayal.

The above quotation has long served as a critical tool for the identification of musical tokens of rage throughout “Solche hergelauf’ne Laffen” and the six other numbers in which Osmin sings, an analytical endeavor that accounts for much of the literature on his character. The letter’s emphasis on tonal relationships, in particular, has prompted us to privilege matters of pitch, contrast, and extremes as symptoms of that rage. Thus many insightful commentaries observe the wide vocal leaps, chromatic coloratura, cavernously low passages, and alternating paces of declamation that frequently punctuate Osmin’s vocal lines, the fluctuating dynamic and varied expressive markings that lend volatility to his accompaniments, and the “Turkish” orchestration that distinguishes him from his Western interlocutors. Important studies among these include Melamed (2010) on the use of Osmin’s low register in contrapuntal settings, Gruber (1994) on musical heterogeneity in “Solche hergelauf’ne Laffen,” and both Bauman (1987, 62–71) and Mahling (1973) on the dramaturgic use of the eighteenth-century alla turca style in Osmin’s music. For more general considerations of Osmin’s character, see Abert ([1919–1921] 2007, 658–85), Betzwieser (1991), and Fábián (1989). For a concise and eloquent account of the syntactical musical challenge that Osmin’s rage presented Mozart, see Kivy (1999, 59–61). Taken together, studies of this sort have demonstrated the consistency of Mozart’s musical approach to Osmin’s hostility across the opera. It should be noted that the distinctive low notes and broad leaps of Osmin’s vocal lines, though often employed dramaturgically by Mozart, were included in no small part to exploit the particular abilities of Ludwig Fischer (1745–1825), the star bass-baritone who premiered the role. Fischer was known for his exceptionally wide range as well as for the fluidity with which he traversed it. For more on his life, voice, and Viennese popularity, see Fischer (2016) and Bauman (1987).

It is thus curious, given the bounty to which Mozart’s treasure map of a letter has led us, that we have largely ignored his plain statement that meter also contributes to the depiction of Osmin’s unbridled expression. In fact, it would seem that Mozart considered the change of meter an integral component of the musical characterization, asserting as he does that it is the combination of harmonic and metrical shifts together that are “bound to be very effective.” The possibility therefore exists that meter plays a more central dramaturgic function in Osmin’s music than we have previously acknowledged. And if we broaden our conception of meter to encompass a variety of metric and rhythmic phenomena (as we have similarly allowed Mozart’s description of remote key relationships to inspire a more general inquiry of musical contrasts), we will be well positioned to identify new ways in which the music of a man in such a towering rage might assume dramatic significance. For broader reflections on the relationship between rhythm and meter, see Rothstein (1989; 2008; 2011) and Hasty (1997); on this relationship in Mozart’s music, see Mirka (2009) and Klorman (2016).

Accordingly, this study examines how Mozart uses variable vocal phrase structures, hypermetric deferment, and text-setting as dramaturgic tools in the depiction of Osmin’s discomposure. As the analyses will demonstrate, Osmin struggles to deliver balanced phrases or adopt a regular hypermeter whenever his emotions intensify throughout his arias “Solche hergelauf’ne Laffen” and “O! wie will ich triumphieren.” The resulting metric, rhythmic, and textual tensions evoke in both numbers a musico-dramatic disorientation similar to the “forgetfulness” described by Mozart in his letter. This study will also observe how Osmin’s introductory aria, “Wer ein Liebchen hat gefunden,” previews his propensity for metric irregularity.

Before delving into the analyses, I shall set down some basic definitions. By “hypermeter,” I refer to recurring groups of three or four measures called hypermeasures that can be perceived by the listener as metric units. The constituent measures of a hypermeasure are alternatingly “strong” and “weak” based on their relative positions. In a quadruple hypermeasure, for instance, the first measure is strong, the second weak, the third slightly less strong than the first, and the fourth weakest of all. The term “hypermeasure” originates in Cone (1968). Irregularities of different sorts can occur within an established hypermeter: the music may switch between duple and triple groups, for instance, or a pattern may be interrupted by the interpolation of a measure of unexpected strength. For analyses that probe the expressive potential of irregular hypermeter, see Cohn (1992) and Rodgers (2011). On types of metric dissonances beyond the hypermetric, see Krebs (1987). The emergence of hypermeter cannot be taken for granted, even in the highly structured music of the late eighteenth century; indeed, I will argue that an erratic projection of strong and weak measures at the start of Osmin’s second aria delays hypermetric entrainment. Rothstein observes that pieces which intentionally invoke improvisation, such as the Baroque toccata or Classical fantasia, “avoid forming hypermeasures in order to preserve a rhapsodic or capricious quality” (1989, 13). To assess how and when hypermeter does or does not emerge, we can identify strong and weak measures based on a variety of parameters: harmonic departures and arrivals, melodic segments, repetitions, contour, the entries and (sub)phrases of participating voices, and accents of any kind (agogic, dynamic, registral, syllabic, textural, ornamentation, harmonic/melodic dissonance, etc.). Such accents, as Malin importantly qualifies, are not the type dependent upon the interpretation of the performer but rather those that inherently “draw attention to themselves” (2010, 41); Krebs further notes that they can represent “any perceptible deviation from an established pattern” (1999, 23). Regarding the assessment of strong and weak measures, see also Lerdahl and Jackendoff (1983) and Rothstein (2011); for more on the determination of metric hierarchy within and outside of hypermeter, see Malin (2010, 35–66).

By “vocal phrase,” I refer to a melodic segment circumscribed primarily by the poetic text and the pauses necessitated by the singer’s breathing and secondarily by melodic, harmonic, cadential, and rhythmic content. Vocal phrases and the phrase structures they comprise are distinct from the phrases and phrase structures conveyed by harmonic progressions or the orchestral accompaniment. Vocal phrase structures therefore may or may not coincide with other phrase structures or with the hypermeter. In fact, the “agreement or conflict” of phrase structure and hypermeter “represents a basic compositional resource” (Rothstein 1989, 13) that can be used toward dramaturgic ends.

The majority of Osmin’s vocal phrases exhibit what William Rothstein calls “neutral barring,” or phrases that cadence on downbeats and begin with either a short upbeat or none at all (2008, 116). This organization derives in part from the structure of the libretto: German verse lacks an accento comune, so the principal stress of a line is determined by textual meaning rather than accentual pattern. The accento comune is the accented penultimate syllable typical of Italian verse. Phrases do not, then, need to move toward an aligned textual accent and cadence, as Italian verse routinely demands. When prioritizing the metrical preference rules that will guide my analyses, I will thus generally privilege the “Grouping Rule,” or “the preference to locate strong beats near the beginning of groups” (Temperley 2001, 357); Lerdahl and Jackendoff (1983, 76) identify this as the “Strong Beat Early” rule. As summarized by Rothstein, metrical preference rules (MPRs) “provide criteria for deciding which of the possible structures is preferred by a listener in a given instance” (2011, 94). These include, for example, the “Harmony Rule” (aligning strong beats with harmonic changes) and the “Linguistic Stress Rule” (aligning strong beats with stressed syllables). For more on MPRs see Lerdahl and Jackendoff (1983), Temperley (2001), and Rothstein (2011). Indeed, Rothstein recommends the precedence of the Grouping Rule in the analysis of German vocal music only “unless other metrical preference rules strongly contradict it” (2011, 97). It should be noted that despite this recommendation, Rothstein (2008; 2011) encourages flexibility in metric analysis, cautioning against the blanket application of theories with “German bias” to Italian- and French-language music and exploring how poetic accent can render measures strong and weak (and especially so at phrase endings). (Of course, there arise such exceptional cases in Osmin’s music and due sensitivity will be afforded them throughout.)

To be clear, the dramaturgic application of hypermetric and phrasal irregularity in Mozart’s operas is by no means limited to the characterization of Osmin, to instances of discomposure, to the German-language works, or to the mature operas. One readily finds examples across Mozart’s operatic oeuvre in which metric imbalances and asymmetrical phrase structures bear the burden of storytelling. To note only a salient few: the alternating phrase lengths that correspond to infidelity and constancy in Bastien’s aria “Geh! du sagst mir eine Fabel” (Tyler 1990, 547); the conflicting hypermeter between singer and orchestra at the outset of Donna Anna’s “Or sai chi l’onore” to help portray that heroine’s steeliness (Schachter 1980, 12); the fluctuating phrase lengths and irregular hypermeter of “Là ci darem la mano” to underscore the Don’s methodical seduction of Zerlina (Burkart 1991); the offset phrasing of Idamante and the orchestra to amplify his lonely plight at the opening of the Idomeneo quartet (Heartz 1980); the odd-numbered vocal phrase structures of “Alles fühlt der Liebe Freuden” that capture Monostatos’s emotional distress (Bastone 2017, 183); and, in another example from the Entführung, Konstanze’s weak-measure entrances in “Ach, Belmonte! ach mein Leben” and subsequent shift from German to Franco-Italian phrasing to convey her assertiveness and strength (Rumph 2005, 184). Another important example, though a bit more modest than those cited above, is Elvira’s offset entrance in “Ah, chi mi dice mai” as a symptom of her bewilderment (Allanbrook 1986, 234). For an additional analysis of meter and text-setting in “Ach, Belmonte! ach mein Leben,” see Bastone (2017, 199–224).

These examples highlight the powerful and varied dramaturgic potential of meter and phrasing in Mozart’s hands. By and large, past studies have probed this potential through analyses of individual numbers; my goal here is to take a step toward broader considerations by engaging a full “network” of arias. This handy term of James Webster’s denotes a group of arias that share any number of dramatic resemblances (character type, dramatic content, operatic genre, language, etc.) and musical resemblances (voice type, aria type, instrumentation, key, meter, form, etc.) (Webster 1991). The full set of a character’s solo numbers can also constitute a network, or even just part of one. In taking up the network of Osmin’s solo offerings, we can explore Mozart’s strategic use of meter and phrase structure across a complete characterization. It is my hope that this study lays the groundwork for similar analyses of even larger networks toward wide-ranging comparisons and conclusions. It is worth noting that Die Entführung aus dem Serail premiered on July 16, 1782, at Vienna’s Burgtheater. Mozart set a libretto adapted especially for him by Gottlieb Stephanie der Jüngere (director of Joseph II’s National Singspiel) from an original by Christoph Friedrich Bretzner titled Belmont und Constanze.

Osmin's Introduction

Osmin sings about the fickle fidelities of women and the capitalizing designs of men who would lure them from their partners throughout his cautionary introductory Lied, “Wer ein Liebchen hat gefunden.” It is a diegetic song, or one that would be sung in real life, and derives in part from two operatic traditions. Strophic folk-like songs of the sort were popular in opéra comique and subsequently in the Singspiel, the older French genre having served as a frequent blueprint in the early development of its German counterpart. For a thorough account of the indebtedness of the Singspiel to French and other international models, see Reiber (1994). Abert’s commentary on this topic also endures ([1919–1921] 2007, 643–57). (Pedrillo’s “In Mohrenland gefangen war” [No. 18], the strophic and enchantingly modal Romanze that initiates the abduction scene in Act 3, belongs to the same class.) Osmin’s griping about feminine inconstancy, though, is typical of his own Turkish servant character type (which itself betrays some influence of the buffo tradition, with such complaining being customary for middle- and lower-class men of the opera buffa stage). We will have occasion to revisit the roots of Osmin’s character type below, but on its crudeness and prevalence in the Oriental Singspiel, see Baron-Woods (2008, 72–74) and Hunter (1998); on musical and dramatic norms for buffo roles in opera buffa, see Platoff (1990) and Hunter (1999, 95–155); and on Osmin’s links to the buffo tradition, see Abert ([1919–1921] 2007, 659–61). Yet with its trudging tempo, chromatically inflected minor mode, and slithering accompanimental winds, “Wer ein Liebchen hat gefunden” forebodes in a manner atypical of its models. There are two dramatically motivated reasons for this. First, Osmin’s text suggests that infidelity is the likely outcome of all romantic relationships, and Mozart’s gloomy setting reflects (what Osmin believes to be) that unfortunate inevitability. Second, the Lied exposes the wariness with which Osmin navigates the world, a misgiving that will prompt and guide virtually all of his behavior throughout the opera. This little Lied—which Hermann Abert praised as “the first time in the history of the German Singspiel [that] an entirely simple song is adapted to the character” ([1919–1921] 2007, 670)—thus establishes the motivation behind all of the grief Osmin will cause the Western protagonists in the acts to come.

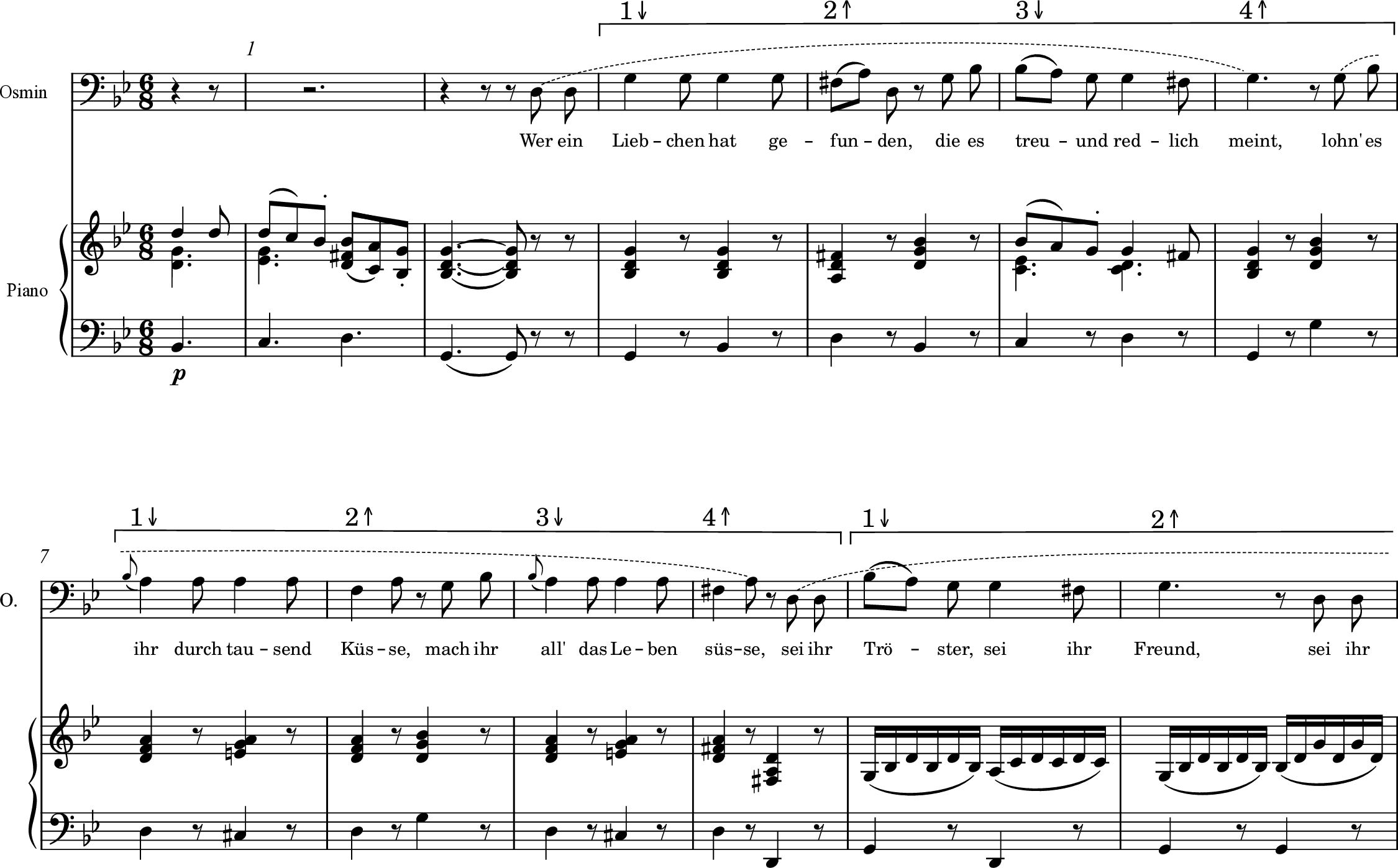

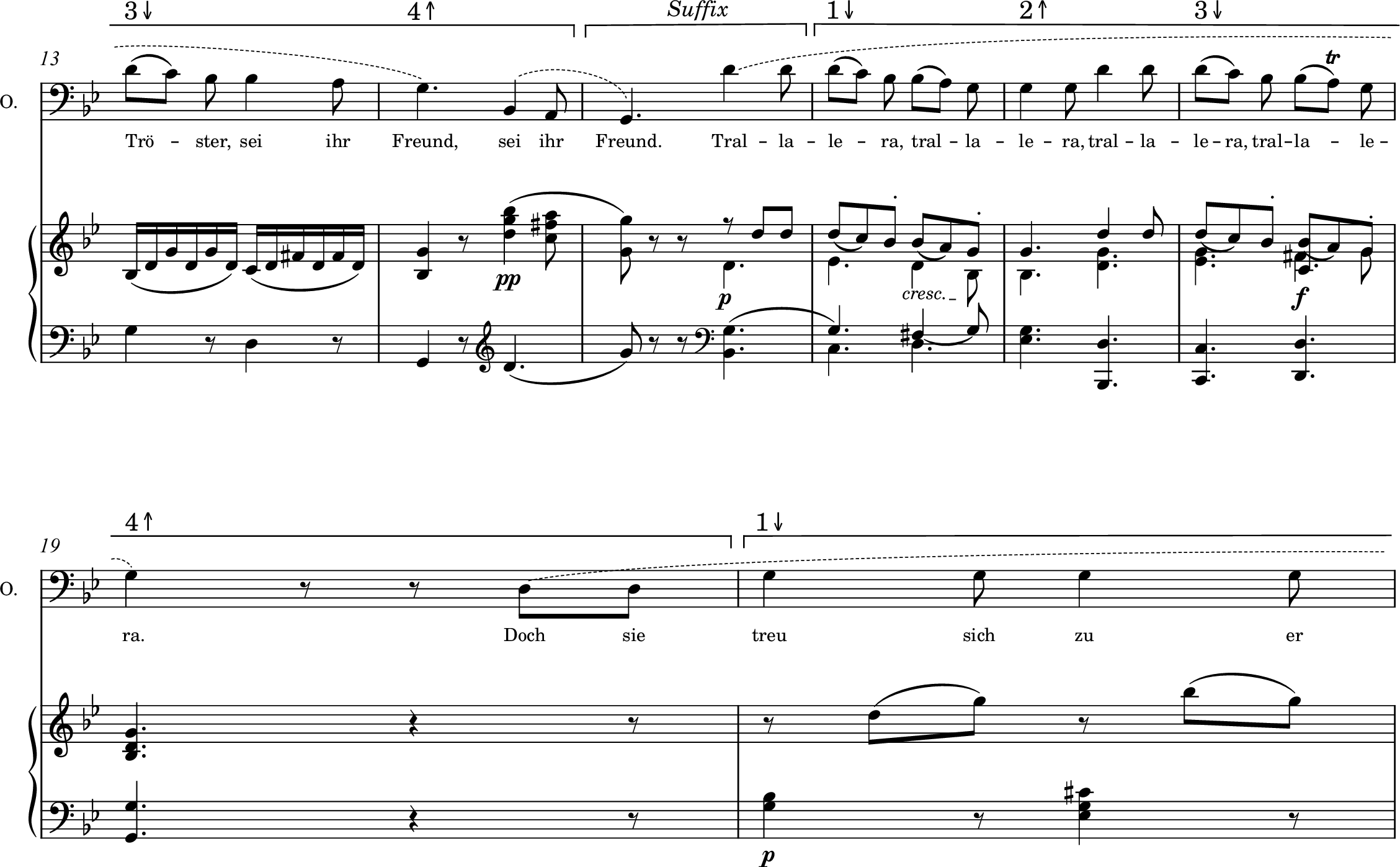

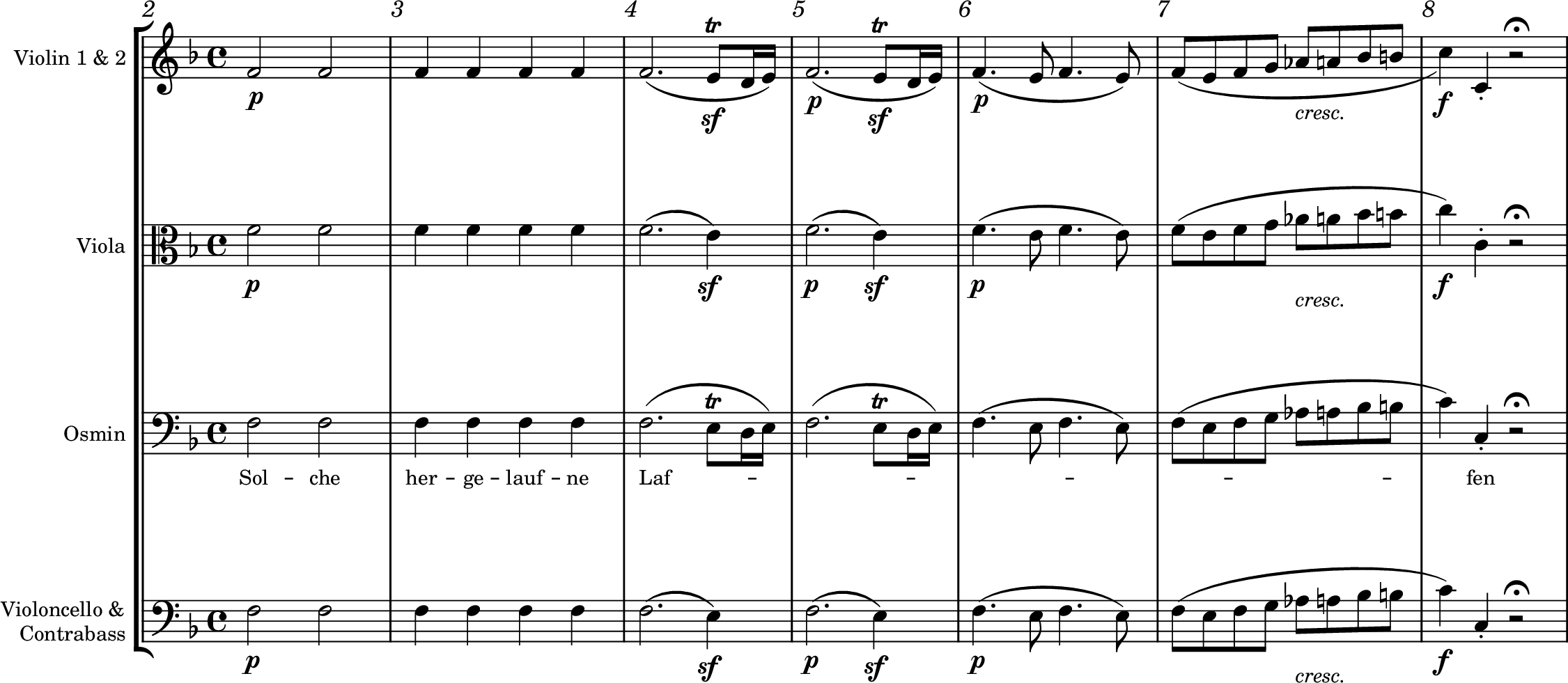

“Wer ein Liebchen hat gefunden” also anticipates the irregularities of vocal phrase structure and hypermeter that will pervade Osmin’s later arias. The Lied is in G minor, 6/8 meter, and varied strophic form, although the accompaniment changes more substantially than does the vocal part as the song unfolds. Three six-line stanzas of trochaic tetrameter comprise the text, which is provided in Example 1. Mozart sets each stanza as a verse with the same phrase structure, so we can take the first verse, which is provided in Example 2, to represent all three. Osmin’s small outburst midway through the third stanza (mm. 40–44) poses a melodic but not structural change to that verse. In this example as well as in those that follow, arrows indicate measure strength (↓ = strong; ↑ = weak); horizontal brackets with Arabic numbers, placed above the staves, indicate hypermeasures; and dotted lines above the vocal part delineate vocal phrase lengths, which represent my own hearing of phrase structure without any necessary correspondence to slurs in Mozart’s score.

The first two couplets each outfit a four-measure vocal phrase (comprised of two two-measure subphrases) that aligns with a hypermeasure (see mm. 3–6, 7–10). Mozart next fashions a couplet out of line five (“sei ihr Tröster, sei ihr Freund”) by similarly setting it twice in a four-measure vocal phrase (and hypermeasure) in mm. 11–14. A fragmented repetition of the line’s final three syllables follows in a suffix echo at the lower octave in mm. 14–15. A suffix is a type of expansion that extends the concluding harmony of a phrase but sits outside the established hypermeter. For more on this common device, see Rothstein (1989, 70–73). One could make the case that m. 15 is a hypermetric elision, as described by Burkhart (1994), but I prefer viewing it as a suffix because Osmin’s second-beat “Tra-la” exhibits a parallel hypermetric function to the vocal upbeats in mm. 2, 6, and 10, which precede hyperbeats. This parallelism is, to my ear, quite pronounced in performance, especially because of the mid-measure rests in the accompaniment (in m. 15). This suffix interrupts the quadruple hypermeter by forcing a metrically weak measure between the end of one hypermeasure and the beginning of another. It also causes a hypermetric shift between each verse. The first verse projects, to borrow Temperley’s term, an “odd-strong” pattern, or a hypermeter in which odd-numbered measures are strong (2008, 305–6). Because of the suffix, though, the final hypermeasure of the first verse begins in an even-numbered measure (m. 16), and the second verse proceeds in m. 20 with an “even-strong” pattern (a hypermeter in which even-numbered measures are strong) until its suffix in m. 32. This suffix then causes a reversion to odd-strong patterning in m. 33 that sustains for the entire third verse. For more on hypermetric transitions in Mozart (and beyond), see Temperley (2008) and Bakulina (2017). The Lied’s slow tempo makes this shift more difficult to perceive than it might be in a faster setting, and because Mozart incorporates the disruptive suffix into all three stanzas, it becomes an expected, almost normalized quirk by its third occurrence. Still, these subtle hypermetric abnormalities hint at Osmin’s penchant for metric unevenness and ensures that the Lied introduces not only his most salient personality traits but his musical idiosyncrasies as well.

In terms of poetic meter, “Wer ein Liebchen hat gefunden”—being comprised entirely of trochaic tetrameter—sets a precedent for all of Osmin’s solo material: “Solche hergelauf’ne Laffen” contains a mix of trochaic dimeter, trimeter, and tetrameter, and “O! wie will ich triumphieren” also uses trochaic tetrameter exclusively. A trochee consists of a stressed (or “long”) syllable followed by an unstressed (or “short”) syllable. Trochaic tetrameter, trimeter, and dimeter feature four, three, and two trochees per poetic line, respectively. Trochees are Osmin’s textual default. The reason is twofold. First, trochaic tetrameter is also the sole poetic meter of the opera’s two Janissary choruses (Nos. 5 and 21b), which along with Osmin’s solo numbers, incorporate to varying degrees Mozart’s “Turkish” musical gestures: raised fourth scale degrees, foregrounded use of piccolo, oboe, or triangle, 2/4 meter, melodies with prominent repetitive thirds or repeated single notes, and, notably, pronounced downbeats, which find their natural textual complement in trochaic meters. For more on the common features of eighteenth-century alla turca style, see Schubart ([1806] 1975), Ratner (1980), Hunter (1998), and Locke (2009); for more on Mozart’s use of it in the Entführung, see Baumann (1987). Trochees are therefore a rhythmic element of Osmin’s Eastern coloration. Second, trochees suit Osmin’s demeanor and communicative style. The emphasized first syllable enables him to begin his every utterance with strength, while the subsequent straightforward alternation between hard and soft seems to reflect something of his obdurate nature and simplemindedness. This use of nothing other than trochaic meters in his solo numbers also underscores the extremity and inflexibility of the opinions expressed within them (e.g., all women are disloyal, all men are opportunists, all foreigners are repugnant).

“Wer ein Liebchen hat gefunden” aligns musical and textual accents without exception (excluding the subjugation of some strong syllables to eighth-note pickups, for which neutral barring allows). But in Osmin’s next arias, Mozart occasionally and dramaturgically obfuscates the trochaic patterning with unexpected accents and disproportionate verse dispersion to depict a more agitated Osmin. Because Osmin sings to a trochaic standard, these anomalies make for easily perceptible deviations that betray his weakening self-command.

Before confronting the two comedic but violent arias that make Osmin a Mozartian household name, a word on the roots of his character is in order. Osmin is a conflation of several musico-dramatic factors and traditions: the increasingly sophisticated impulses of Mozart’s maturing dramatic sensibilities, the comic and musical tendencies of Osmin’s opera buffa counterparts, and the eighteenth-century European custom of stereotyping the behavior, morals, and musical styles of those from the East. Ralph Locke describes Osmin as a paragon of such caricature, writing that he is “unquestionably nasty, and his nastiness is understood as tied up with his adherence to real or supposed Turkish customs of his day” (2009, 322). Indeed, lowborn male characters of Ottoman lineage were often afforded the very worst of Western beliefs about their ethnicities and Islamic faith, their characterizations marked by barbarity, superstition, lasciviousness, indulgence, and hypocrisy. These traits were almost invariably underscored by the instrumentation and compositional devices of the alla turca style, itself a caricature of sorts, which Mary Hunter persuasively argues was “associated with extreme masculinity (bravado, fierceness, an obsessive interest in domination)” and then “mapped, in a classically Orientalizing manner, onto clear markers of ethnic difference” (1998, 57).

Mozart seems to have recognized Osmin’s rage as both a universally human emotion and as a distinctly uncivilized Turkish one. His letter to his father, quoted above, does not impute such overwhelming anger to Turkish men exclusively, and it is conceivable that Mozart himself had recently suffered from some rage-induced forgetfulness: his struggles with the Archbishop Colloredo transpired earlier that very year. Still, markers of “Turkishness” permeate Osmin’s characterization, the comedy of which relies on his overeager thuggish urges and lack of emotional restraint together with diverse and copious applications of the alla turca style. To be sure, Osmin bears musical and dramatic responsibilities beyond those of the typical eighteenth-century operatic Turkish servant—his role was expanded by the librettist at Mozart’s behest—but it is important to remember that he remains in many ways a product of the ill-founded Eastern stereotyping so commonplace in Austria at the close of the eighteenth century. Mozart asked Stephanie to expand Osmin’s role, at least in part, to help win the audience’s favor. The Viennese loved to laugh and they loved to hear Ludwig Fischer (the singer who premiered the part); Osmin’s increased presence ensured they would have more of both. For more on this calculation and the long gestation of the Entführung libretto, see Bauman (1987).

Osmin's Anger

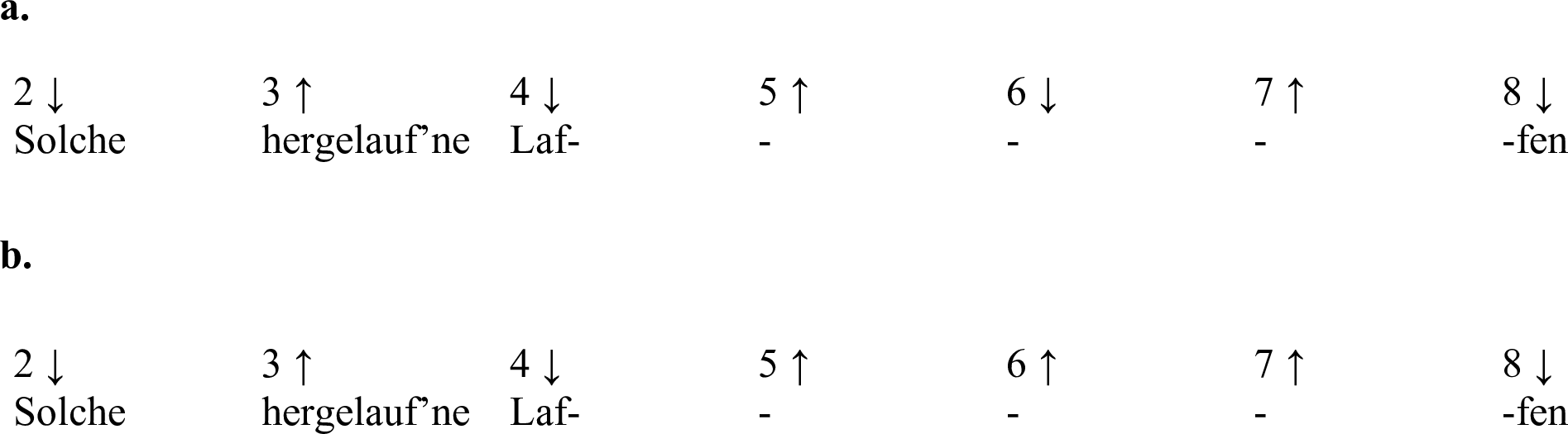

“Solche hergelauf’ne Laffen” is in F major, common time, and marked allegro con brio. Its text is provided in Example 3a. My analysis begins with a brief review of its form, an outline of which, based on the Type 2 sonata identified by Hepokoski-Darcy (2006), is provided in Example 3b. On the Type 2 sonata form, see Hepokoski-Darcy (2006, 353–87). In Example 3b and throughout this analysis, P = primary theme, TR = transition, S = secondary theme, C = closing zone, and the apostrophe (‘) represents the medial caesura. By “rotation,” I refer to a full “cycle through the governing layout (P TR ‘ S),” including post-S closing zones, where they exist (Hepokoski-Darcy 2006, 353). Rotation 2 contains the defining features of this type: it begins with a full off-tonic presentation of P as a developmental space before a tonic presentation of S supplies the tonal resolution. That Rotation 2 begins with P in the submediant rather than the dominant represents for Hepokoski-Darcy a second-level default (2006, 373). In Idomeneo, Mozart twice similarly represents Elettra’s mental instability at the same formal juncture: her “Tutte nel cor vi sento” is in D minor but begins its Rotation 2 in C minor and her “D’Oreste d’ajace” is in C minor but begins its Rotation 2 over a chromatic passage (and then the dominant). In both rotations, P and S are separated by transitions in which Osmin importantly takes part. And the post-rotational codas, of course, introduce new music and text, the second being cast in A minor (rather than the expected F major) and 3/4 time to ensure that both man and music “forget” themselves. It is essential to remember that the dramatic impact of the meter change would have impressed more strongly upon the opera’s original audience than it does upon modern ears, since eighteenth-century listeners were accustomed to the relative fixedness of meter within individual pieces and movements. As Danuta Mirka writes: “In the eighteenth century the constancy of notated meter was taken for granted by both composers and listeners. Virtually every piece or movement was written with one time signature from beginning to end” (2008, 83).

Gerold Gruber descriptively writes that Osmin “crashes, trips, and stumbles” (1994, 494; my translation) into the aria, an impression he derives from the chromatic melisma of the opening passage and the half-measure pause that follows it. Yet one could argue further that it takes Osmin until S (of the exposition) to find surer footing, as fluctuating vocal phrase lengths and the erratic projection of strong and weak measures permeate P and TR with imbalances that delay the establishment of a hypermeter. Osmin’s fitful phrasing accommodates the overwrought expressions of a man teeming with anger.

Example 4 provides the seven-measure phrase with which Osmin enters the aria in unison with the strings but purposefully omits the aria’s first measure, an F-major chord with fermata for the strings alone. It is unlikely that the chord was ever part of Mozart’s conception. As Gerold Croll writes in the critical notes of the Neue Mozart Ausgabe:

The question of whether [the measure] was originally by Mozart cannot be definitely answered, but the transmission and, in our opinion, the context on stage and in the drama and the musical craftsmanship speak against it. . . . [I]n the Vienna score copy used by Mozart the chord was not originally there: it was added subsequently in another hand. When this happened, and whether with Mozart’s approval or not, can no longer be ascertained. . . . Simply seeing it as a support for the singer (‘helping to find the way’ to the note) is not an acceptable view of the chord. Mozart (as conductor at the keyboard) would have found some other way, in keeping with the theater practice of the day, to meet this need.”

That Ludwig Fischer, the first Osmin, would have needed such aid seems doubtful given his noted abilities. Moreover, if he had fumbled the note, Mozart probably would have complained about it: on July 20, 1782, he reported to his father that Johann Ernst Dauer (the first Pedrillo) and Fischer bungled the opening of the first-act Trio in performance. “I was in such a rage,” Mozart recalled, “. . . that I was simply beside myself and said at once that I would not let the opera be given again without having a short rehearsal for the singers” (Anderson 1997, 808). Tending to agree with Croll’s assessment that the first measure is not Mozart’s own, I will not account for it here.

Osmin’s opening gambit is what Hepokoski-Darcy would call a “weak-launch option”: a P that opens piano with “the onset of some sort of bustling crescendo effect” (2006, 66). The phrase presents and prolongs the tonic note for five measures (mm. 2–6) before launching a chromatic ascent to the dominant (mm. 7–8). A melisma on the first syllable of “Laffen” (“dandies”) starts on the downbeat of m. 4 and occupies more than half of the phrase. It is a brooding and asymmetrical preamble that anticipates Osmin’s imminent eruption. It is also a bit fiddly to parse.

One could make the case, as shown in Example 5, for a regular alternation of strong and weak measures. Measure 2 is strong because of Osmin’s entrance; m. 3 is weak because the repeated unison F extends the melodic and harmonic stagnation. Measure 4 follows as strong (even though it, too, contains repetitions of F) owing to the agogic accent that sets a stressed syllable and sounds like the goal of the previous measure. Measure 5, though nearly identical to m. 4, follows as weak because its downbeat is marked p and does not receive a new textual articulation from Osmin. Measure 6 is trickier, but we might hear it as strong because it breaks from the repetition of the previous two measures in favor of a livelier diminution of those measures’ dotted half and quarter notes. Measure 7 ensues as weak as Osmin offers a gliding, rhythmically even prolongation of the melisma, the chromatic ascent and crescendo of which generate momentum into the downbeat of the strong m. 8, where Osmin abruptly concludes the phrase.

There are drawbacks to this interpretation, however. We are not compelled to read m. 6 as strong. It requires some aural determination to hear it as such, and we could just as easily mark it weak, as shown in Example 5, because it extends the melisma and embellishes the tonic note as the previous three measures had done. Moreover, the unnaturally accented fourth beats of mm. 4 and 5, both punctuated with an sf and emphasized by a semitone trill, lessen the impact of the downbeats of mm. 5 and 6.

Of these two possible hearings, I favor that of Example 5b because it dramaturgically complements the text and text-setting. The passage begins straightforwardly enough: the strong syllables of the trochaic meter perceptibly align with strong musical beats (and the weak syllables with weak beats) through the downbeat of m. 4, with agogic accents on the downbeats of mm. 2 and 4 that help to render those measures strong. Such deliberate declamation intoned on the tonic note indicates that Osmin is in command of his emotions. But upon reaching the word “Laffen” in m. 4—crucially the first direct reference to those blasted “dandies”—Osmin abandons his orderly delivery and wanders off in a melisma. The dotted rhythms of mm. 4–6 twitch with his agitation, their emphasis on the semitone between E and F seeming to reflect and widen a crack in his composure. He lingers so long on the syllable “Laf-” that it takes a first-time listener four measures to discern what word he even intends to sing. And the chromatic ascent of m. 7 subverts the tonic before it is clear whether the tonality is major or minor. To hear mm. 5–7 as metrically weak, then, is to understand them as a lapse in Osmin’s focus brought on by the mention of his enemies. It is a small-scale application of the musico-dramatic premise upon which Mozart will construct the second coda: just as Osmin loses his train of thought while stewing about the Laffen, so too does his music lose itself in a meandering succession of weak measures and harmonic ambiguity.

The opening passage also serves as a catalyst for the irregular vocal phrase structure that will prevent the establishment of a hypermeter until the onset of S. Example 6 provides an interpretation of the vocal phrases in P and TR beginning at m. 8. To begin, note the consecutive strong measures that mark Osmin’s reentrance (mm. 8, 9), delineate between two of his phrases (mm. 11, 12), and accentuate the juncture between P and TR (mm. 18, 19). Note also, beginning at m. 8, Osmin’s odd-numbered and inconsistent phrase lengths: 3 + 5 + 3. The five-measure phrase (mm. 12–16), as shown in Example 6, is comprised of 4 + 1. Example 6 interprets mm. 12–16 as projecting a regular alternation of strong and weak measures. One could convincingly argue that all of these measures are strong owing to the similar rhythmic contents of mm. 12–15 and the fp markings that punctuate each downbeat. I favor the alteration of strong and weak measures because of the suspensions in the winds, which clearly mark only the downbeat of m. 12.

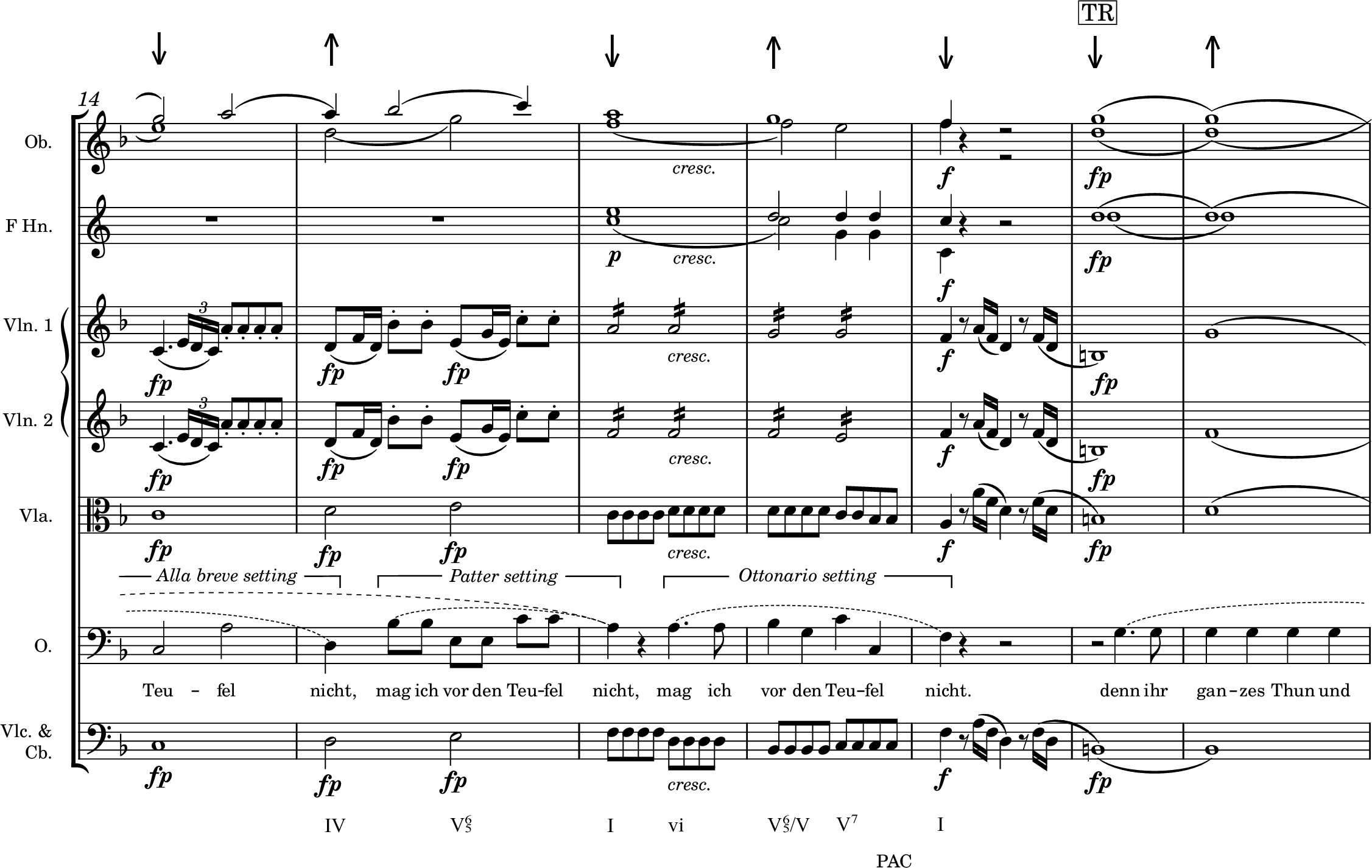

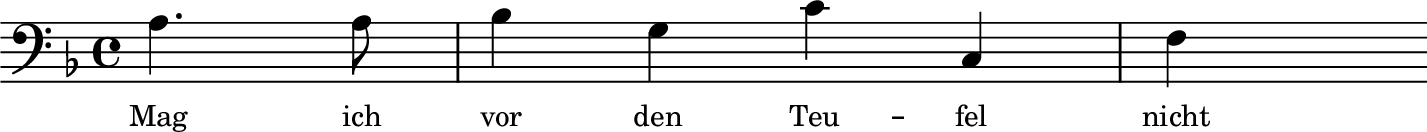

Such a volatile, pattern-avoidant phrase structure suggests that Osmin’s anger is already beginning to undermine his composure. The text-setting and accompaniment evidence the same, especially so across mm. 12–18. Osmin first presents the final line of the first stanza, “mag ich vor den Teufel nicht,” in a sequentially ascending alla breve setting that ends over the subdominant (mm. 12–15), stranding him without new text on inconclusive harmonic ground. Allanbrook (1983) insightfully discusses the (extra)musical significance of alla breve meter in the broader eighteenth century as well as in Mozart’s operas. He then impatiently repeats himself in a patter-like rhythmic diminution that extends the melodic sequence in order to more quickly arrive at the tonic (mm. 15–16). The resulting imperfect cadence is not strong enough to conclude P, though, and Osmin is compelled to deliver the line a third time in a broad Italianate ottonario setting over a perfect authentic cadence (mm. 16–18). We will have cause to discuss the ottonario in more detail below, but regarding this common setting, see Webster (1991, 130–40) and Lippmann (1978); on the related “Italian barring,” see Rothstein (2008; 2011). Nearly half of P is thus devoted to this single textual line, thrice offered in as many styles. Increasingly frustrated, Osmin struggles not only to adopt balanced phrases, but to align a decisive textual delivery with a decisive harmonic event. It is dramatically significant, too, that the orchestra first diverges from the vocal line just as Osmin begins this threefold delivery (the opening ten measures having been offered in nearly perfect unison). Across mm. 12–14, the violins accompany Osmin with the motive marked “motive A” in m. 12 of Example 6. As motive A sequentially rises with Osmin, its downbeat fp, impulsive triplet descents, and pecking eighth-note repetitions reflect, if not agitate, Osmin’s incipient rage.

Looking ahead, Osmin begins the transition with a three-measure phrase that brusquely concludes in a strong measure (mm. 19–21, see Example 6). The orchestra continues without him in m. 22 as the first violins reintroduce motive A and exchange it with the second violins in a rising stepwise sequence across a six-measure passage of regularly alternating strong and weak measures (mm. 22–27). I interpret the alternating strong and weak measures in this six-measure passage according to Rothstein’s “Parallelism Rule,” which is rooted in the early-twentieth-century work of Eugen Tetzel: “When a motive is immediately repeated at the same or another pitch level, in the same or another voice, the strongest beat in the first statement is normally stronger than the strongest beat in the second statement” (2011, 96). I read m. 22 as strong because of the accented downbeat, which occurs after three beats of rest. Despite the patent strength of m. 22, though, Osmin reenters on the downbeat of the weak m. 23, rendering it strong for his own part and forging ahead for four measures in conflict with his accompaniment (as indicated by the arrows above the vocal part in mm. 23–26 in Example 6). I interpret Osmin’s m. 23 as strong according to two MPRs outlined by Rothstein (2011, 96): the “Event Rule,” which aligns strong beats with event-onsets (the event being Osmin’s reentrance after a full measure of rest), and the aforementioned Linguistic Stress Rule (the preference to align a strong beat with a strong syllable). This multivalent interpretation recognizes the singer and orchestra as distinct agents with a largely complementary but not interdependent relationship, each agent possessing its own determinant elements that may or may not be congruent with those of the other. By “multivalent interpretation,” I build on the term “multivalence” as defined by Webster (1991, 103–4): “temporal patternings” of various “domains” (rhythm, meter, melodic content, text, etc.) “are not necessarily congruent and may even be incompatible,” and “the resulting complexity and lack of unity is often a primary source of their effect.” Here, Osmin’s incongruous entry suggests that his intensifying anger is already the cause of some “forgetfulness.”

The remainder of the transition unfolds like a recitative, Osmin offering an ad libitum passage punctuated by rests and fermatas that culminates in the medial caesura (see Example 6, mm. 27–31). Burton hears this shift to recitative-like style as a marker of Osmin’s “unsteadiness” and borrows the Greek term metabole to describe the illustrative musical function of the pauses (2004, 366–73). Burton presents a sensitive analysis of the aria, taking into account the dramatic implications of phrasing and meter (especially in the second coda). Being the most salient and rhythmically active voice as well as the guiding interpreter of the ad libitum marking, Osmin determines measure strength throughout. The text-setting also suggests that Mozart has purposefully foregrounded his part. In mm. 27 and 29, Mozart sets the second, weak syllable of the trochee “doch mich” on the third, accented beat, allowing Osmin to caution through undue emphasis that he should not be underestimated (“but me—I cannot be deceived”).

The whole passage hits a metric reset button, so to speak, for the aria. When S begins in m. 32, Mozart immediately establishes a quadruple hypermeter that he sustains until the arrival of Rotation 2. It is important to note, though, that Rotation 2 reproduces the text and vocal phrase structure of the exposition’s P and TR almost exactly, so the phrasal and metric disorder must be borne a second time—and off the tonic, besides (see Example 3b). The only significant (non-harmonic) difference between P in Rotations 1 and 2 is the compression of mm. 18–19 into one (m. 72). Where the listener likely expects the utmost stability, Mozart instead repeats the phrasal muddle and prolongs the harmonic tension.

The irregular phrase structures and hypermetric deferral throughout P and TR of “Solche hergelauf’ne Laffen” exhibit Osmin’s disregard for “order, moderation, and propriety” well before the arrival of the second coda, for although his rage becomes most acute there, it is by no means absent earlier in the form. Indeed, Osmin’s eruption in the second coda represents the culmination of a long and angry meditation that begins with the aria’s first phrase.

Osmin’s anger also manifests musically in the sometimes-overlooked first coda, where abnormalities of text-setting pop in a newfound fever pitch. To appreciate this, we must first make a few general observations about eighteenth-century text-setting. In the metered German and Italian librettos of the time, the syllabic count and accentual pattern of each poetic verse-type generated and limited the rhythmic options at a composer’s disposal for text-setting. Rhythmic profiles, to borrow James Webster’s term (1991, 130–40), are the rhythmic patterns suitable for each verse-type owing to their arrangements of stressed and unstressed beats. Some profiles were applicable to both German and Italian verse, some were not; a number of profiles could be used for multiple poetic verse-types, others could not. Eighteenth-century composers relied upon these profiles, and they permeate the operatic literature of the period. Webster also rightly observes that when Mozart remarked to his father during the composition of the Entführung that “verses are doubtless the most indispensable thing for music,” he likely meant that “poetic lines . . . imply tangible rhythmic profiles” (1991, 132). For another excellent source on Mozart’s rhythmic profiles and how they compare in his settings of German and Italian texts, see Lippmann (1978). On rhythmic profiles and their dramaturgic functions in the Entführung, see Bastone (2017, 49–84).

Up to the first coda of “Solche hergelauf’ne Laffen,” Mozart calls upon some of the most frequently used profiles for three- and four-stress textual lines in German (and Italian) opera of the time. The first of these is the pure ottonario profile, which privileges the third and seventh syllables, or the second and fourth syllabic stresses, with downbeat placement, as shown in Example 7a. The second is the ottonario with midpoint caesura; this distributes the syllables much like the pure ottonario but inserts a rest after the first two poetic feet, as shown in Example 7b. A third profile, which aligns the first and third syllabic stresses with downbeats and uses an agogic accent for the first, is shown in Example 7c. Finally, there is the profile that aligns each syllabic stress with a downbeat, as shown in Example 7d. This profile saturates the numbers of the Entführung in which Mozart deploys the alla turca style (heavy downbeat emphasis being an important feature thereof). There are other profiles in the aria, of course, and moments in which textual stress and musical stress do not align; Mozart’s dramaturgic setting of “mich” in mm. 27 and 29, as described above, is the most salient of these. But taken as a whole, Mozart’s text-setting throughout Rotations 1 and 2 can only be described as accommodating syllabic weights with commensurate rhythmic emphases using a typical variety of conventional rhythmic profiles of the day.

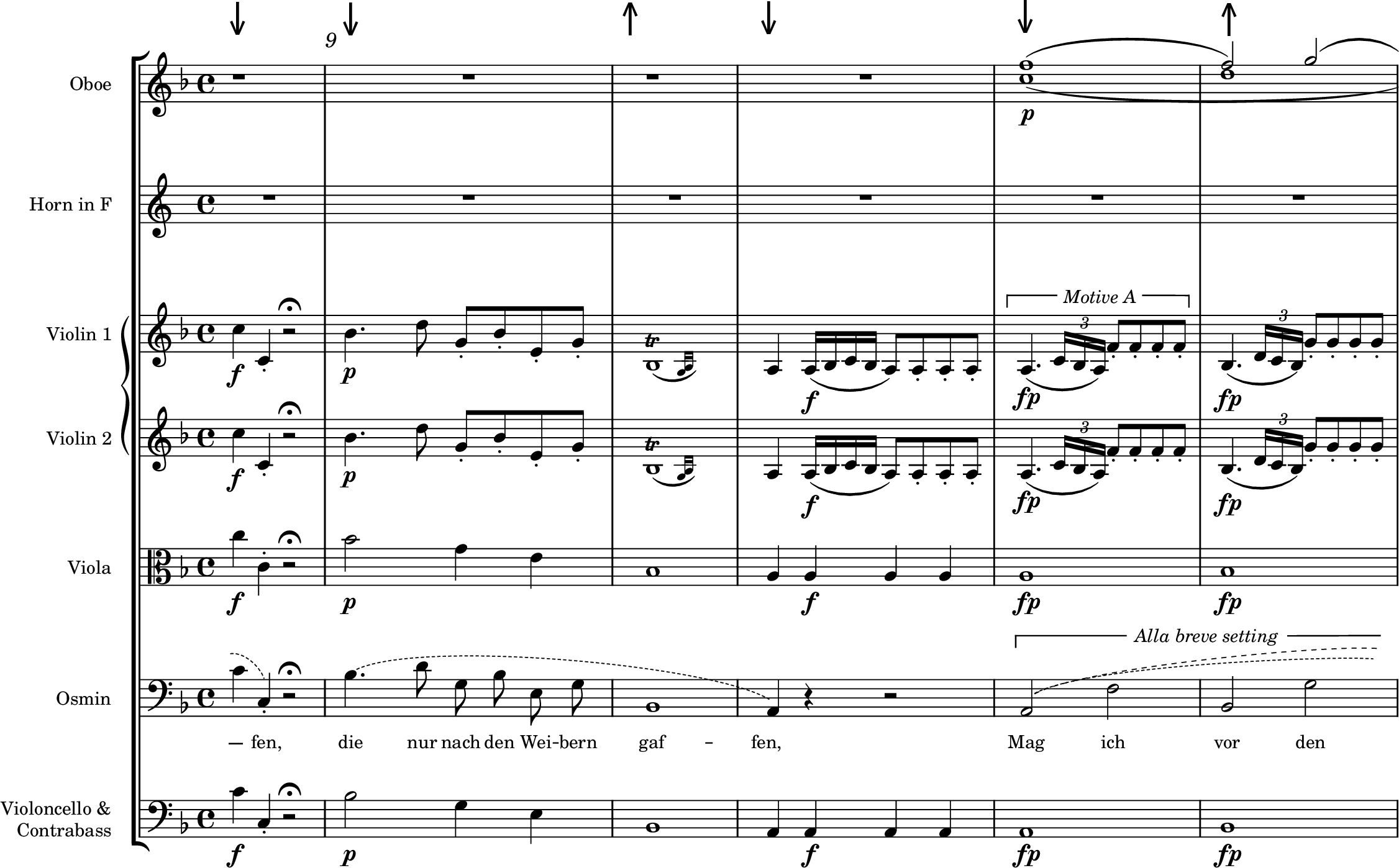

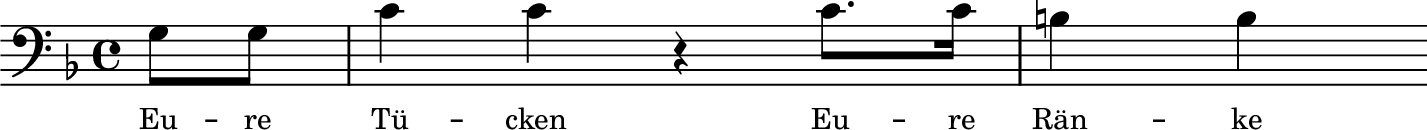

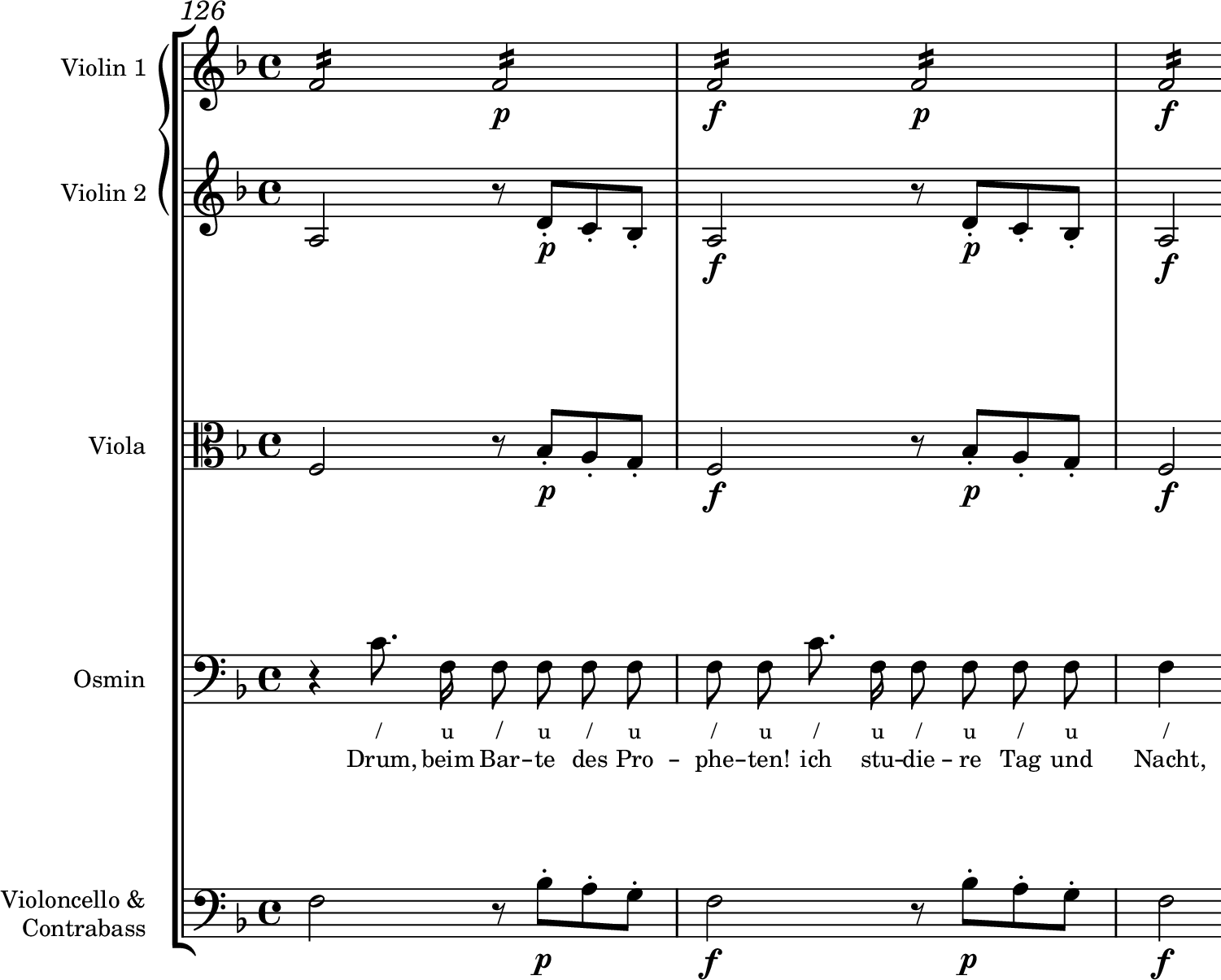

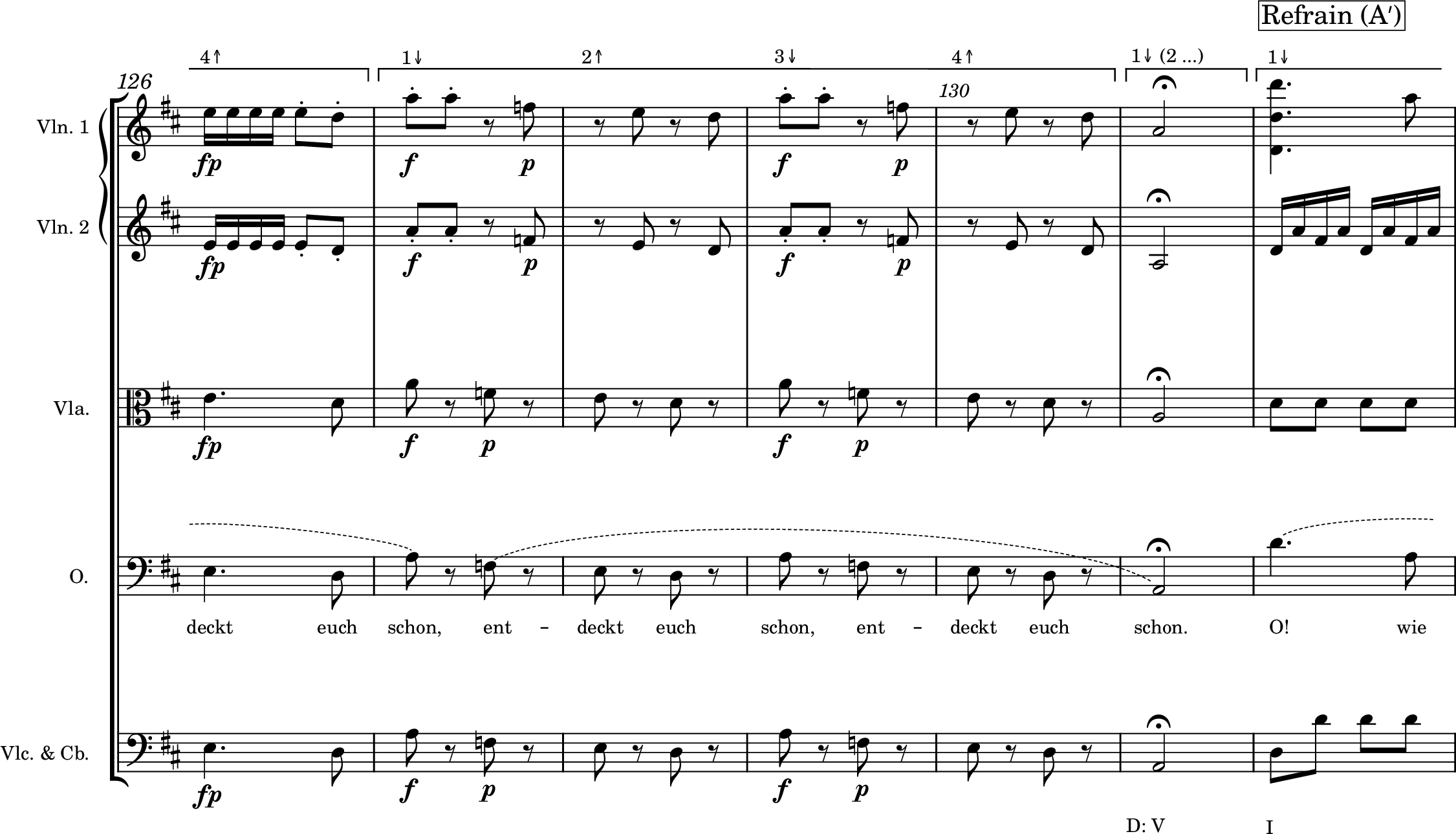

It is, then, quite obvious when the association of textual and musical stress becomes less strict at the onset of the first coda, notably the place where Osmin begins to issue his first threats. The fifth stanza outfits this section; to begin, Osmin offers it in full over the tonic (mm. 126–130) and then repeats it over the dominant (mm. 130–134). Throughout both presentations, Mozart sets the first strong syllable of each line on the weak second beat of the measure and places it a fifth or an octave higher than the repeated Fs and Cs with which Osmin delivers the ensuing syllables. Example 8 provides the first two textual lines set in this manner. In receiving both textual and melodic emphases, the weak second beats become a source of volatility that makes the whole passage feel slightly off-kilter despite the unwavering harmonic stability and Osmin’s otherwise mechanical declamation. If it is in the second coda that his rage boils over, then surely it begins to simmer here. Mozart explained to his father, in the same letter quoted at the outset of this article, that “[t]he passage ‘Drum beim Barte des Propheten’ is indeed in the same tempo, but with quick notes,” implying that the faster declamation was meant to reflect Osmin’s “gradually” increasing rage (Anderson 1997, 769).

Osmin's Triumph

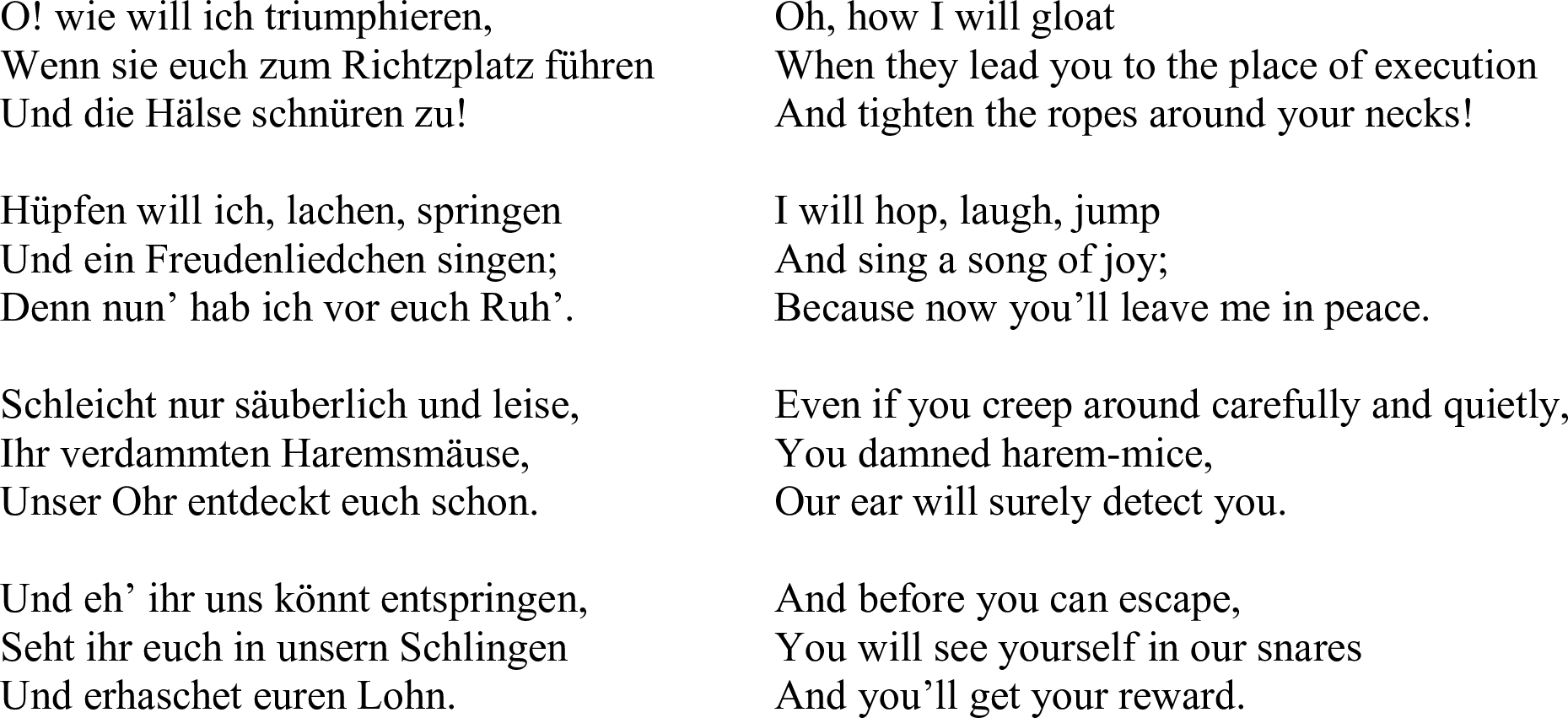

Osmin offers his exuberant victory aria “O! wie will ich triumphieren” after his minions catch the Western captives escaping from the palace near the end of Act 3. The delight and anger roused within him by the capture are inextricable; his text, provided in Example 9a, is in one line gleeful and in the next combative. Although satisfied at last by the detention of Pedrillo and Belmonte, he cannot suppress his violent resentment that Haremsmäuse like them exist at all.

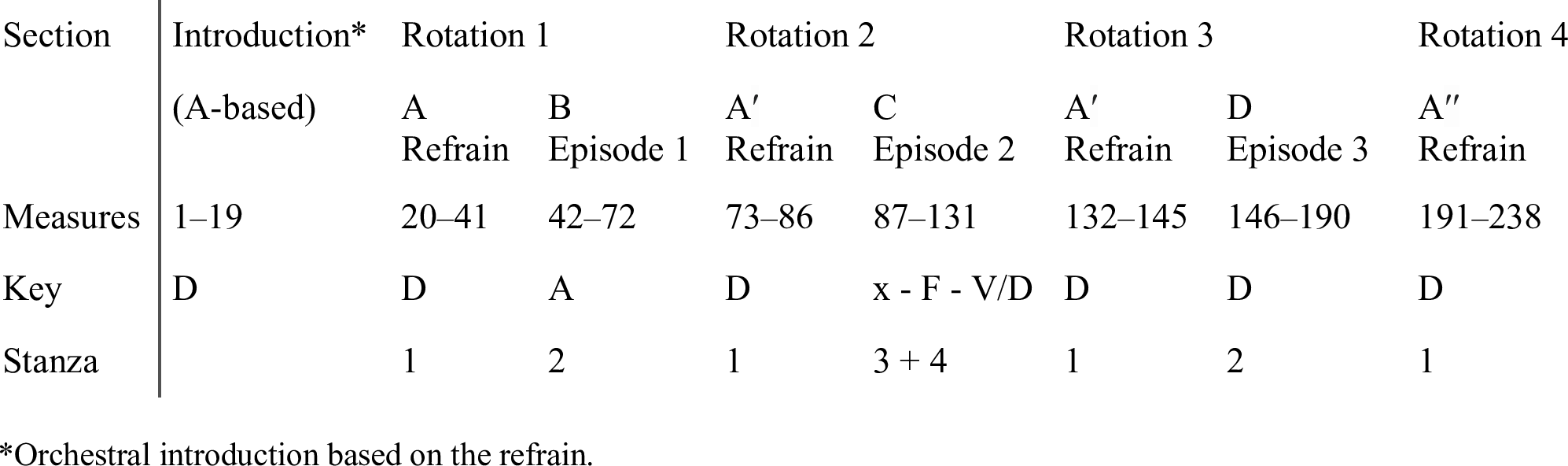

I read the aria’s form, which is outlined in Example 9b, as a modified version of the symmetrical seven-part rondo identified by Hepokoski-Darcy (2006, 402–4). Their abstract three-and-a-half rotation model outlines “an AB–AC–AB′–A design, in which episode 3 (B′) is a tonic transposition of the off-tonic episode 1 (B)” (2006, 402). This allows Rotation 3 to provide a tonal resolution analogous to that secured by the recapitulatory space of a sonata form. (We cannot go so far as to call the aria’s form a sonata-rondo [or a Type 4 in Sonata Theory], since it does not contain the requisite transition between A and B in the first rotation.) Hepokoski-Darcy calls this TR the “defining feature” of the sonata-rondo (2006, 394), repeatedly noting that when A and B are “merely juxtaposed thematic blocks” with no transition between them, the formal structure does “not rise fully to the level of the ‘sonata-rondo’ in the strictest sense of the term” (2006, 402–4). It should be noted that episodes 2 and 3 of “O! wie will ich triumphieren” do feature at their conclusions transitional passages of dominant preparation for the return of the tonic refrain. Example 9b makes more of a distinction between episodes 1 and 3 than the abstract model, however. These episodes are very closely related: they set the same text and are melodically analogous between mm. 50–72 (episode 1) and 169–190 (episode 3). I have chosen to label them B and D (rather than B and B′) because they start with different music, Osmin opting for a syllabic setting to begin B and a melismatic bravura setting to begin D. Such virtuosic display at the end of a major character’s final aria would have been expected by both singer and audience in 1782 and, for me, does not preclude reading the form as a symmetrical seven-part rondo: episode 3 reproduces much of episode 1 and supplies Rotation 3 with tonal resolution. That being said, this analysis is primarily concerned with the refrain and episode 2, both of which are marked by metric and phrase-structural turbulence.

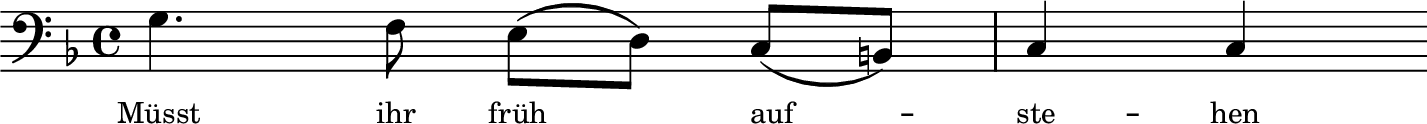

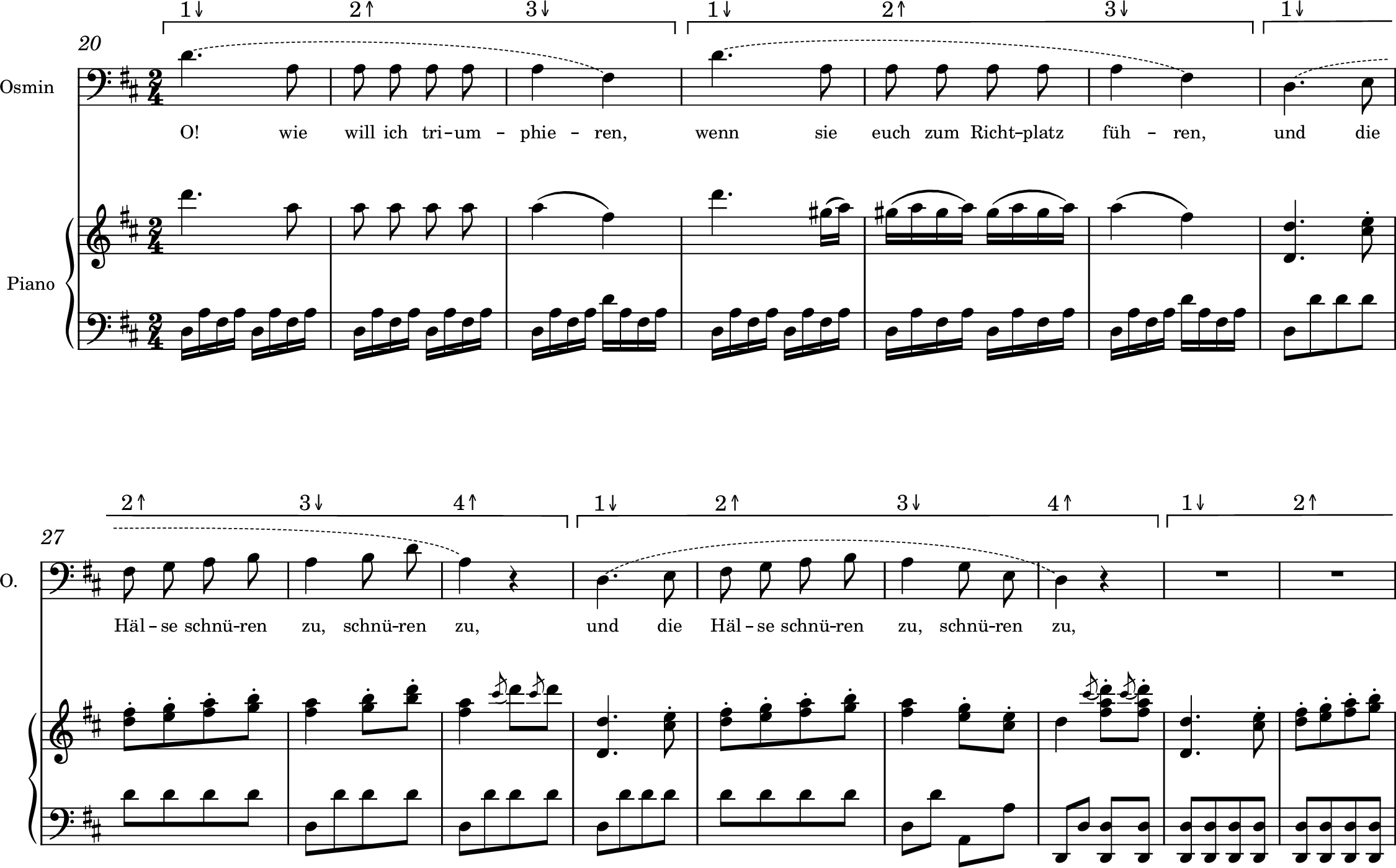

An irrepressible, maniacal glee brims every refrain as Osmin envisages the new prisoners at the scaffold. Mozart writes three variants of the refrain, but we will begin with that labeled A in Example 9b, the hypermeter and vocal phrase structure of which is provided in Example 10. The section opens with two triple hypermeasures (the outer constituent measures of which are strong and the middle weak) made up of two vocal phrases of equal lengths. The third vocal phrase is also three measures long (mm. 26–28) and initially suggests another triple hypermeasure, but Osmin’s phrase extension via textual fragmentation (“schnüren zu,” mm. 28–29) renders mm. 26–29 a quadruple hypermeasure. Although offered at a different pitch level, Osmin’s expansion via “schnüren zu” is a textual and rhythmic repetition that recalls Kirnberger’s concept of echo-repetition: “one can repeat the last measure of a three-measure phrase as an echo and thus form from them a rhythmic unit of four measures” ([1793] 1982, 410). Three statements of this phrase and extension (the orchestra supplying the expected melody when Osmin drops out in mm. 34–35) subsequently project three quadruple hypermeasures across mm. 30–41. That the triple hypermeter would normalize to a quadruple pattern is perhaps expected; as Rothstein writes, “when a piece begins in a non-duple meter, it commonly reverts to duple hypermeter later on, as if to emphasize that its beginning was metrically abnormal” (1989, 39). Rodgers (2011) as well as De Souza (2019), who notably reports a corpus study of hypermetrical irregularity in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century symphonic sonata movements, both observe the rarity of extended passages of triple hypermeter.

What should we make of this only-in-hindsight abnormality? Mozart again seems to call upon that now-familiar paradigm of a passionate man losing himself in the throes of expressive abandon. If, in “Solche hergelauf’ne Laffen,” Osmin experiences a “towering rage” (to borrow Mozart’s words), then here he is similarly overwhelmed by a towering joy. The giddying effect of his long-sought victory consumes him, and the initially irregular metric packaging of his line is symptomatic of his unrestrained emotional response. Perhaps, then, it is not only when Osmin becomes enraged, but rather when he is overcome by any strong feeling that he “forgets” his sense of self and (musical) syntax.

Much like the primary theme and transition of “Solche hergelauf’ne Laffen” return to wreak phrasal havoc in that aria’s second rotation, variants of the refrain return to compromise the metric stability of “O! wie will ich triumphieren.” The refrains labeled A′ in Example 9b are comprised exactly of mm. 20–33 of A, and the closing A′′ begins with the first three hypermeasures and vocal phrases of A before continuing with modified melodic material in a quadruple hypermeter. Truncated refrains were common in the second and third rotations in of the late-eighteenth-century rondo (see Hepokoski-Darcy 2006, 388–403). Section A′′ diverges from A at m. 199, where Osmin delves into obsessive textual fragmentation that the orchestra underpins with incessant cadential gestures in order that he might finish the aria with a real bang. A quadruple hypermeter persists throughout. Of this vocal material, Abert wrote that “Osmin is no longer capable of forming an orderly melodic line but simply avails himself of odd phrases and fragments of his main theme, flogging them to death in his delight at the thought of imminently strangling his enemies” ([1919–1921] 2007, 683). Every presentation of the refrain thus introduces and corrects a triple hypermeter, providing a cyclic reminder of Osmin’s exultation and the intemperance with which he savors it.

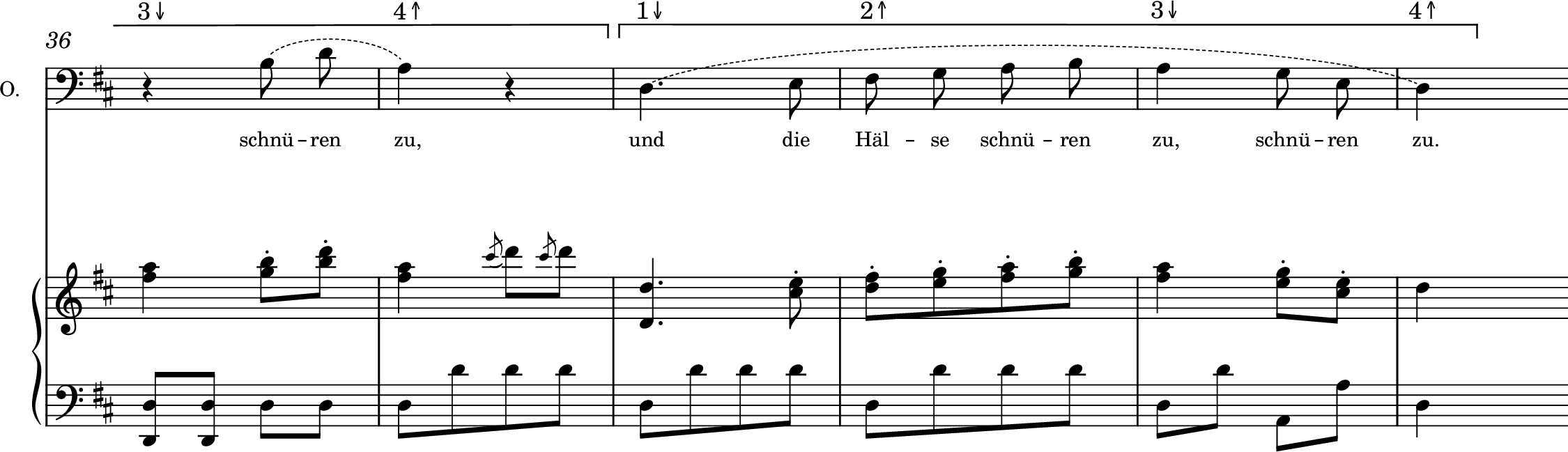

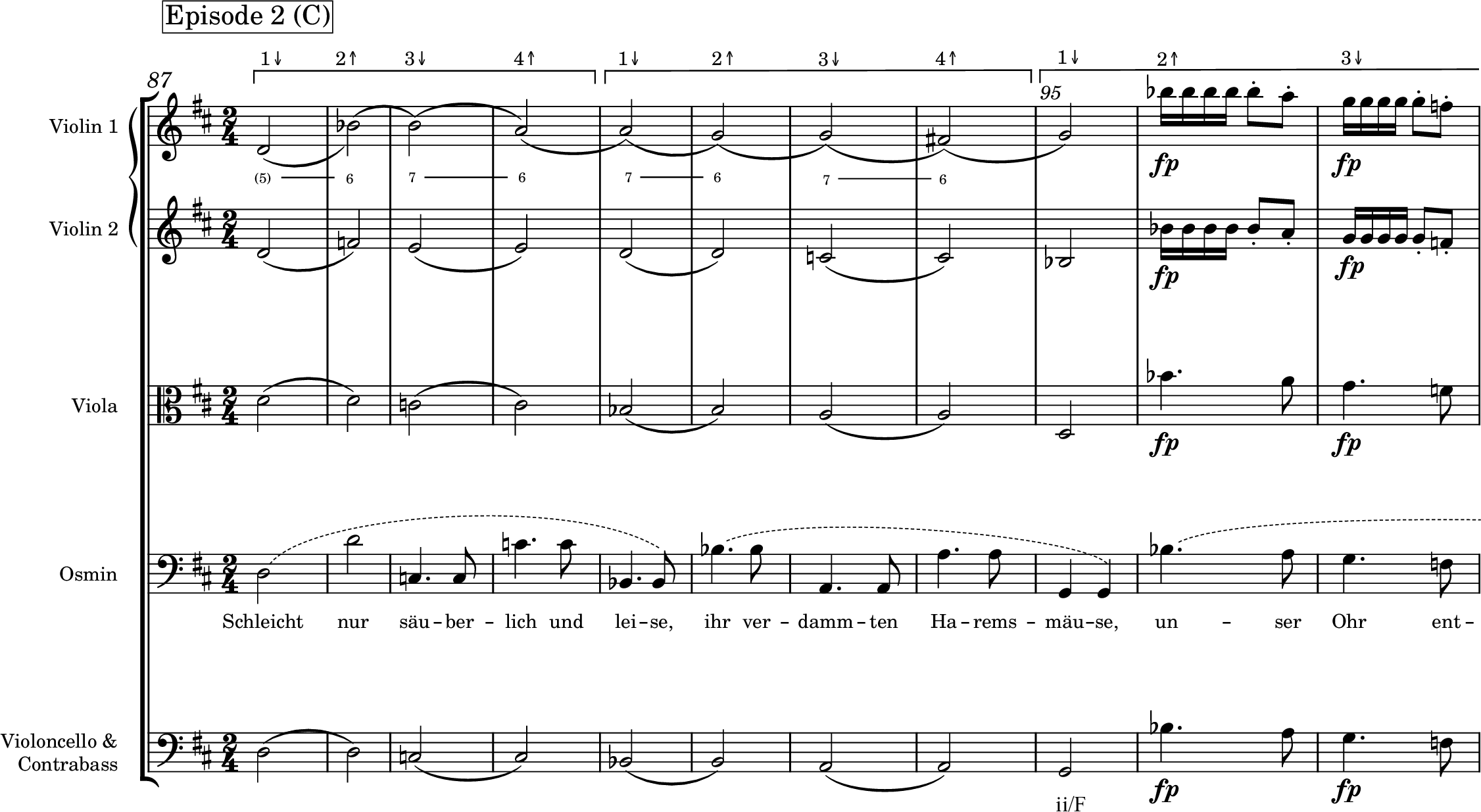

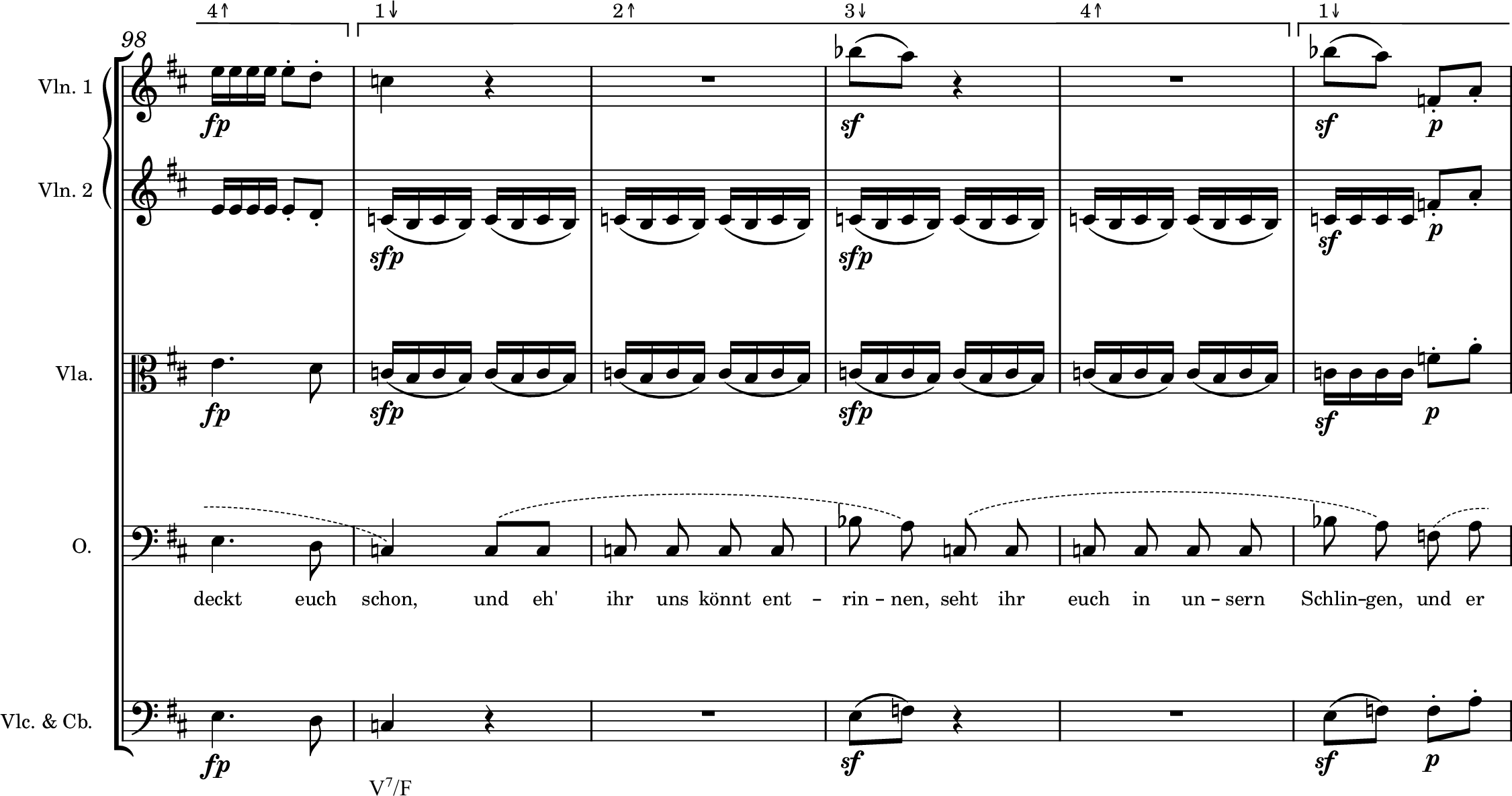

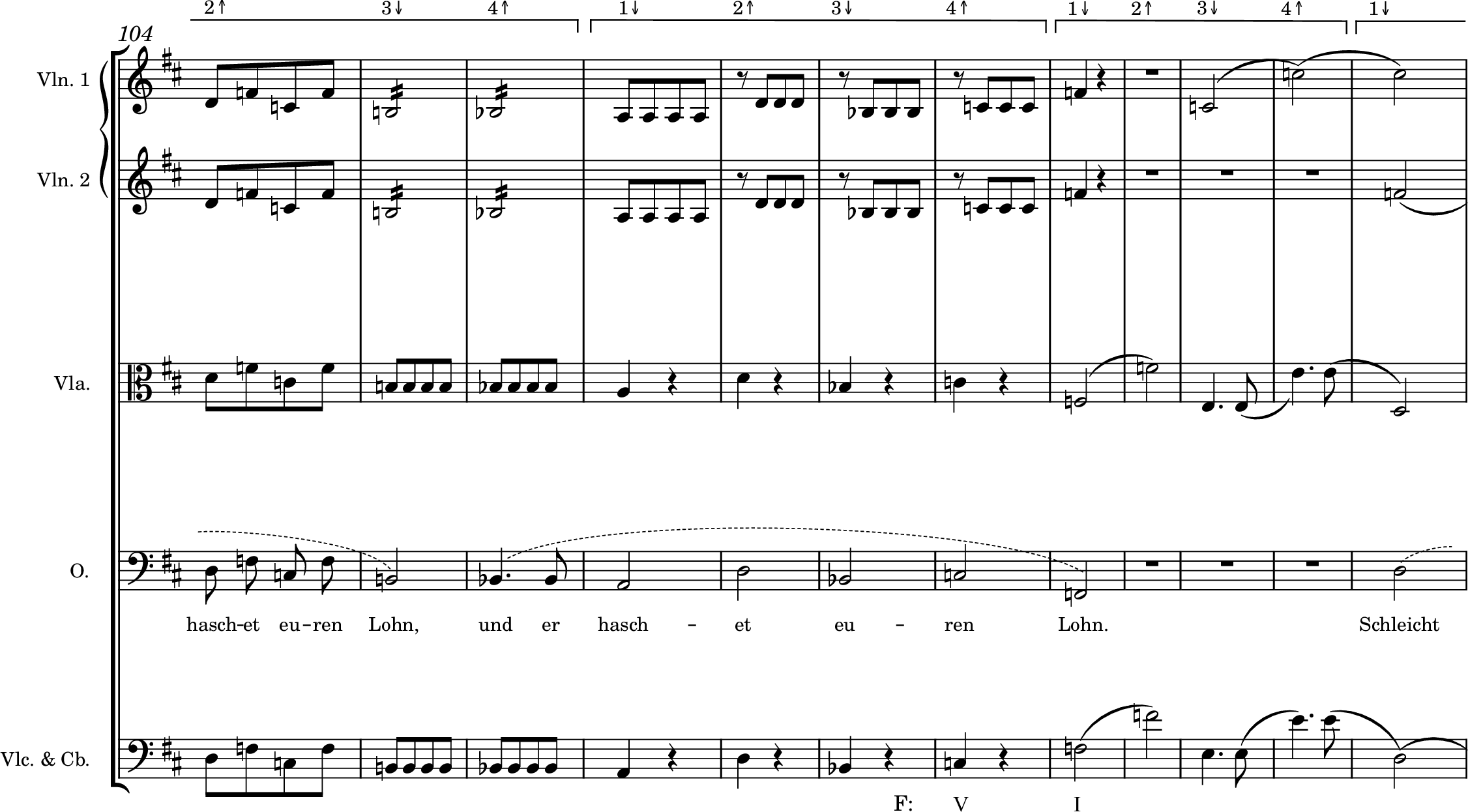

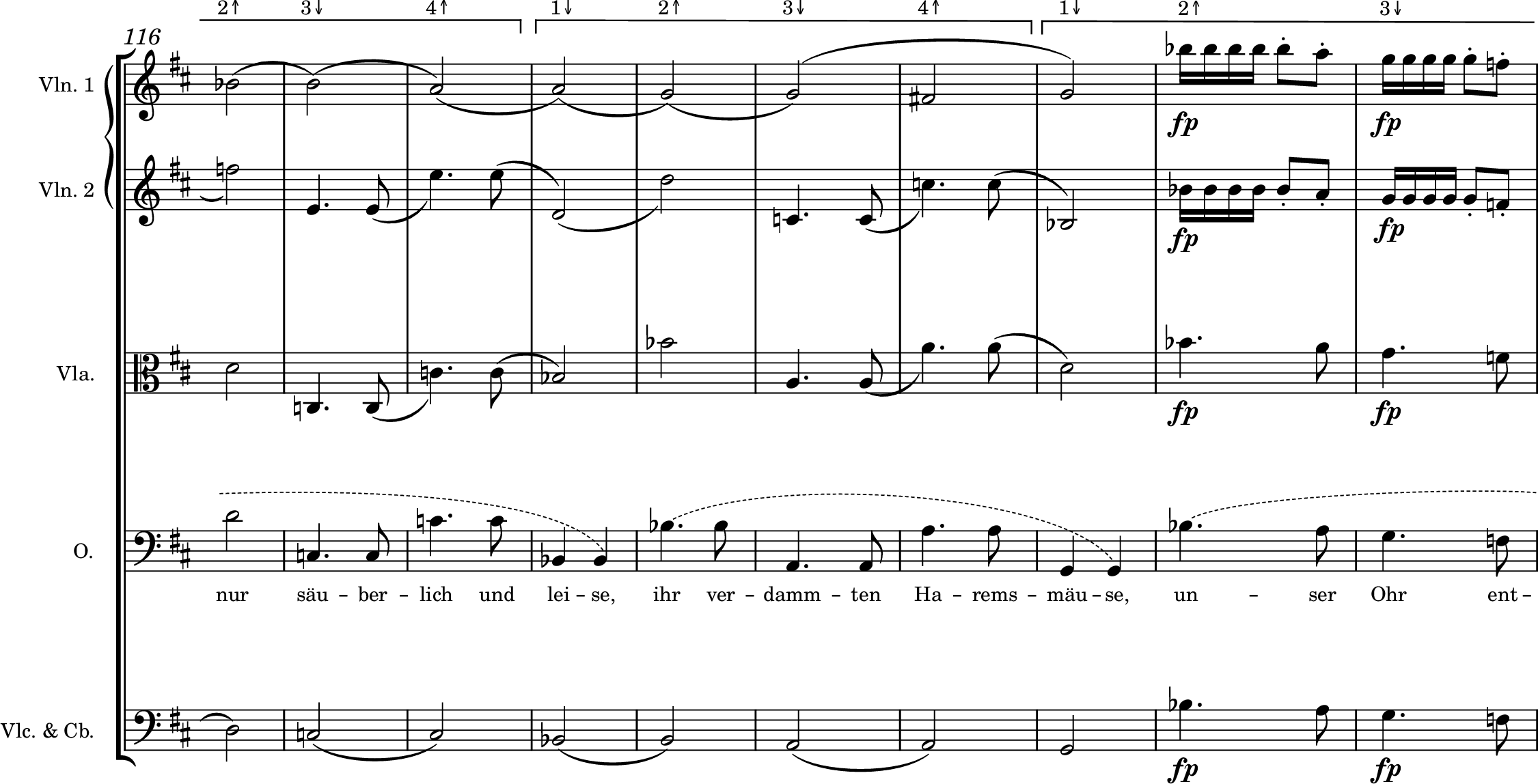

Osmin’s jaunty demeanor in the refrain yields to a more characteristic surliness in episode 2, throughout which he issues his final threats to Belmonte, Pedrillo, and any other Haremsmäuse like them who may plot a furtive slip through the palace gates. Distrust and indignation thus reside at the heart of the aria just as they do in the heart of the man, and Mozart seizes one last opportunity to depict Osmin’s maniacal hostility with a variable vocal phrase structure. Atop the regular quadruple hypermeter that furnishes the entire episode—and which is made easily perceptible by the orchestra and harmonic plan—Osmin superimposes vocal phrases of changing lengths that begin and/or end in conflict with every hypermeasure.

Example 11 provides episode 2 in full; through its first nine measures, the strings project a quadruple hypermeter by articulating in strong measures and resolving in weak ones. To begin, the second violins, violas, cellos, and basses offer stepwise descending half notes tied over every other bar line, marking each metrically strong measure with the articulation of a half-note pair throughout mm. 87–94. The second violins begin with an ascending minor third in mm. 87–88 but follow the stepwise pattern of the violas, cellos, and basses thereafter. Against their descent, beginning in m. 89, the first violins issue a lazily sinking 7–6 suspension series in two-measure increments that places every resolution in a metrically weak measure. The passage ends with the arrival of G minor in m. 95; functioning as ii of F, the harmony initiates a modulation to that key that will occupy the music through m. 111 (but more on that later).

One could argue that Osmin supports the regular alternation of strong and weak measures with his pendular melody throughout mm. 87–95, his lower swoops lending a weightiness to the strong measures and his higher reaches lending a buoyancy to the weak ones. But this is a superficial support undercut by his eschewal of the orchestra’s explicit four-measure groupings. He begins with a five-measure phrase (mm. 87–91) that violates the outer boundary of the episode’s first hypermeasure by spilling into the second and continues with a four-measure phrase (mm. 92–95) similarly offset from the hypermeasures beneath it. This creates two obfuscating tensions. First, Osmin finishes both of these phrases in the initial strong measure of a new hypermeasure, inducing a sense of closure where metric momentum begins anew. Second, Osmin’s second phrase begins in the weak second measure of the hypermeasure, imposing a starting point where a metric current is already in motion. Moreover, the unequal lengths of these phrases asymmetrically dispose the rhyme scheme of the text. Although the rhyming line-endings of the stanza’s first two lines, “leise” and “-mäuse,” make for a clumsy rhyme, it is one the listener can anticipate given that the two preceding stanzas (set in A and B respectively, as shown in Example 9b) began with two rhyming lines (see Example 9a). Mozart correlates the phrasal and metric positions of “leise” and “-mäuse” by situating each in the final measure of a vocal phrase and in the first measure of a hypermeasure (mm. 91, 95), but he also catches the listener off guard by placing “-mäuse” one measure earlier than expected, the second phrase falling one measure short of the first’s five-measure precedent. (This imbalance is accomplished by allowing the weak syllable “nur” of the first textual line and vocal phrase to occupy an entire measure [m. 88] rather than relegating it to an eighth note of a dotted-quarter and eighth-note pairing, as Mozart subsequently treats weak syllables through m. 94.)

The opening nine measures of episode 2 pass as a slow-motion reel, Osmin’s every word and melodic undulation sprawled across each measure in unavoidable contrast with the preceding declamatory bustle of the refrain. The passage conjures the delicate, creeping movements with which Osmin alleges the Haremsmäuse will attempt to surreptitiously enter the palace. But the bobbing melody and artificially slower tempo (resulting from the tutti rhythmic augmentation) also engender a lull that helps to enhance the shock value of Osmin’s next eruption: in m. 96, Osmin jolts up the interval of a tenth over a tutti downbeat fp as the orchestra likewise shifts registers and the violins swap their languorous half notes for agitated sixteenths (see Example 11). The outburst is made all the more unpredictable by its placement in the weak second measure of the hypermeasure. The fp marking, registral shift, and change of accompanimental figuration are tempting reasons to interpret m. 96 as metrically strong. I favor hearing it as weak, though, because it prolongs the G minor harmony attained in m. 95 (an unequivocally strong measure) through to m. 97. Moreover, even strong accents like the downbeat fp of m. 96 do not automatically oblige strong measures; Cone asserts that “there is no necessary correlation between strong measures and dynamic accents” (1968, 31). Osmin continues in a formidable melodic unison with the orchestra to warn the foolhardy harem mice in the ensuing phrase of mm. 96–99 (“Unser Ohr entdeckt euch schon”) and concludes at the start of a new hypermeasure over the dominant of F (m. 99).

In no other moment across Osmin’s solo offerings does the music assume such a narrative function as in the opening of episode 2, where the vocal phrase structure, text-setting, and harmonic plan combine to enact the cat-and-mouse pursuit evoked by the text. Osmin’s cat first lies in wait across mm. 87–95, the languid suspensions, metrically tensional phrase structure, and premature rhyme conclusion indicating to the more discerning Haremsmaus that this is a false calm. Duly poised, the cat then pounces on his victim mouse in the vulnerably weak m. 96 with a registral leap, dynamic contrast, and the imposing melodic shadow of the orchestra. The arrival of the dominant seventh of F in m. 99 signals the cat’s victory by setting the first clear harmonic goal of the episode. And as the cat sings through m. 111 about the just punishment the prisoner mouse will suffer, the music moves to and cadences in F (mm. 110–111), thereby underpinning the cat’s triumph with a harmonic stability that was not present during his chase.

Backtracking a bit in Example 11, we should note that Osmin remains out of step with the hypermeter as he takes his modulating victory lap in mm. 99–111. He begins three phrases on the upbeats to weak second measures (mm. 99, 101, 103) and consistently concludes his phrases in strong measures (either the first or third of the hypermeasures) through the cadence of m. 111. This is, perhaps, like the ebullient and metrically uneven refrain, another example of Osmin losing his emotional and musical composure in the fervency of his joy. The delight he derives from his role as captor—both of Belmonte and Pedrillo and in his cat-and-mouse fantasy—simply overwhelms him.

Osmin repeats the “Schleicht nur” passage of mm. 87–99 in mm. 115–127 (see Example 11). The repetition features new figuration in the accompaniment and the inclusion of the oboe and bassoon (not shown in Example 11); additionally, the harmonic goal is the dominant of D in preparation for the refrain’s return in m. 132. We might also note that the low strings and vocal part suggest a canon between mm. 111–119, subtly echoing the “stalking” narrative first introduced in mm. 87–95. (I am indebted to an anonymous reader of Theory and Practice for this clever observation.) The repetition diverges from its model in m. 127 (analogous to m. 99) as Osmin lingers on the textual fragment “entdeckt euch schon” through m. 131. He concludes in what initially sounds like the first measure of a new hypermeasure (m. 131), but Mozart writes a fermata above the tutti half note to force a pause on the dominant of D. The prolongation subsumes the remaining three measures of the hypermeasure and (temporarily) suspends the hypermeter, since no matter how modestly or generously the singer interprets the fermata, there are no pulses to mark the time. It is like a bolt from the blue, then, that the refrain returns in m. 132 with its startling downbeat exclamation and boisterous rhythms. The cat has pounced again.

In the letter quoted at the outset of this article, Mozart wrote of a man whose rage causes him to overstep “all the bounds of order, moderation, and propriety.” Mozart used this description to justify the double coda of “Solche hergelauf’ne Laffen,” but in doing so he also suggested broader truths about Osmin’s character and the way his emotional expressivity might manifest musically. The inconsistent vocal phrase structures, hypermetric deferrals, and misalignment of musical and syllabic stresses in “Solche hergelauf’ne Laffen” represent the debilitating effects of Osmin’s rage before that rage becomes all-consuming in the second coda. The recurring hypermetric correction of the “O! wie will ich triumphieren” refrain lends tumult to an unusual victory speech, demonstrating that any emotion Osmin experiences strongly can compromise his mental and musical coherence. And the friction between the hypermeter and vocal phrase structure in that aria’s episode 2 helps to musically narrate Osmin’s deeply vindictive fantasy of ensnaring those men he dislikes. Through irregularities of phrase structure, hypermeter, and text-setting, Mozart developed an idiosyncratic metric language that could suit the haywire expression of an indignant man whose emotions often get the better of him.

Although Osmin’s ensembles are beyond the scope of this essay, the finale of Act 3 provides a revealing moment with which to conclude our discussion of his music. We are not concerned with the finale’s quotation of “Solche hergelauf’ne Laffen”—in both the aria and the finale, that famous passage projects regular duple-based phrases and hypermeter—but rather with Osmin’s entry into the ensemble. The quoted passage is that which opens the aria’s second coda with the text “Erst geköpft, dann gehangen” (in the aria, starting at m. 147; in the finale, at m. 75).

The finale is a tuneful vaudeville in F major. To begin, each Western protagonist offers the Pasha a celebratory verse that concludes with a tutti refrain in which Osmin—who is usually staged seething in the corner—also reluctantly takes part. Blonde, the Englishwoman whom Osmin has romantically pursued for the last three acts, is the last of the Europeans to sing. On Osmin’s interest in Blonde and its effect on his character, see Fábián (1989), Mahling (1973), and Joncus (2010). As shown in Example 12, she concludes her verse by pointing to Osmin and asking the Pasha whether anyone should be expected to “endure” such an “animal” (mm. 61–65). The question is too injurious for Osmin to ignore, and at last he enters in m. 64 with his own (melodically modified) verse, preventing the expected presentation of the refrain and reinterpreting the final weak measure of Blonde’s phrase. Osmin continues with a regular quadruple hypermeter thereafter. Mozart even marks a double bar halfway through m. 64, visually separating Osmin’s contribution from the rest.

It is a briefly humanizing moment for the dour caretaker. Osmin had remained silent through all the others’ rapturous verses—even that delivered by his nemesis, Pedrillo, at whom he leveled “Solche hergelauf’ne Laffen” in the first act. It is Blonde’s jab that lures Osmin into the fray, her public rejection so hurtful that he cannot wait even one measure to respect the metric order and defend himself. One wonders if perhaps it is not only the presence of the Laffen and Haremsmäuse that cause Osmin so much grief, but also the absence of a Liebchen—which, unlike the men he cautions in his first aria, he has not yet found for himself.

Works Cited

Abert, Hermann. [1919–1921]. 2007. W.A. Mozart. Translated by Stewart Spencer. Edited by Cliff Eisen. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Allanbrook, Wye Jamison. 1983. Rhythmic Gesture in Mozart: Le nozze di Figaro and Don Giovanni. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Anderson, Emily, trans. and ed. 1997. The Letters of Mozart and His Family. 3rd ed. Edited by Stanley Sadie and Fiona Smart. London: Macmillan Reference Limited.

Bauklina, Ellen. 2017. “Canons as Hypermetrical Transitions in Mozart.” Music Theory Online 23.

Baron-Woods, Kristina. 2008. “Bassa Selim: Mozart’s Voice of Clemency in Die Entführung aus dem Serail.” Musicological Explorations 9: 67–93.

Bastone, Danielle. 2017. “The Analysis of Musical Dramaturgy in Mozart’s Die Entführung aus dem Serail.” PhD diss., The Graduate Center of the City University of New York.

Bauman, Thomas. 1987. W. A. Mozart: Die Entführung aus dem Serail. Cambridge Opera Handbooks. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Betzwieser, Thomas. 1991. “Die Europäer in der Fremde: Die Figurenkonstellation der Entführung aus dem Serail und ihre Tradition.” In Mozarts Opernfiguren: Grosse Herren, rasende Weiber, gefährliche Liebschaften, edited by Dieter Borchmeyer, 35–48. Bern: Paul Haupt.

Burkhart, Charles. 1991. “How Rhythm Tells the Story in ‘Là ci darem la mano.” Theory and Practice 16: 21–38.

Burkhart, Charles. 1994. “Mid-Bar Downbeat in Bach’s Keyboard Music.” Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy 8: 3–26.

Burton, Deborah. 2004. “Orfeo, Osmin and Otello: Towards a Theory of Opera Analysis.” Studi Musicali 2: 359–85.

Cohn, Richard L. 1992. “The Dramatization of Hypermetric Conflicts in the Scherzo of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.” 19th-Century Music 15: 188–206.

Cone, Edward T. 1968. Musical Form and Musical Performance. New York: Norton.

Croll, Gerhard. Critical Report. In Neue Mozart-Ausgabe: Digitized Version, Series II, Group 5, Volume 12: Die Entführung aus dem Serail, translated by William Buchanan, 7–35. Salzburg: Internationale Stiftung Mozarteum. http://dme.mozarteum.at.

De Souza, Jonathan and David Lokan. 2019. “Hypermetrical Irregularity in Sonata Form: A Corpus Study.” Empirical Musicology Review 14, No. 3–4. The Ohio State University Libraries. http://emusicology.org/issue/view/227.

Fábián, Imre. 1989. “Osmin’s Freud und Lied: Überlegungen zu Mozarts Entführung.” In Opern und Opernfiguren: Festschrift für Joachim Herz, edited by Ulrich Müller and Ursula Müller, 59–64. Anif-Salzburg: Müller-Speiser.

Fischer, Ludwig. 2016. The Autobiography of Ludwig Fischer: Mozart’s First Osmin. Edited and translated by Paul E. Corneilson. Malden: Mozart Society of America.

Gruber, Gerold Wolfgang. 1994. “Osmin, oder: Was thematisiert die Musik?” In Die lustige Person auf der Bühne, vol. 2, edited by Peter Csobádi, 493–500. Anif-Salzburg: Müller-Speiser.

Heartz, Daniel. 1980. “The Great Quartet in Mozart’s Idomeneo.” Music Form 5: 233–56.

Hasty, Christopher F. 1997. Meter as Rhythm. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hepokoski, James, and Warren Darcy. 2006. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth Century. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hunter, Mary K. 1998. “The Alla Turca Syle in the late Eighteenth Century: Race and Gender in the Symphony and the Seraglio.” In The Exotic in Western Music, edited by Jonathan Bellman, 43–73.

Hunter, Mary K. 1999. The Culture of Opera Buffa in Mozart’s Vienna: A Poetics of Entertainment. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Joncus, Berta. 2010. “‘Ich bin eine Engländerin, zur Freyheit geboren’: Blonde and the Enlightened Female in Mozart’s Die Entfuhrung aus dem Serail.” The Opera Quarterly: 552–87.

Kirnberger, Johann Philipp. [1793]. 1982. The Art of Strict Musical Composition. Translated by David Beach and Jürgen Thym. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Kivy, Peter. 1999. Osmin’s Rage. Cornell Paperbacks edition. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Klorman, Edward. 2016. Mozart’s Music of Friends: Social Interplay in the Chamber Works. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Krebs, Harald. 1987. “Some Extensions of the Concepts of Metrical Consonance and Dissonance.” Journal of Music Theory 31: 99–120.

Krebs, Harald. 1999. Fantasy Pieces: Metrical Dissonance in the Music of Robert Schumann. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lerdahl, Fred and Ray Jackendoff. 1983. A Generative Theory of Tonal Music. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Lippmann, Friedrich. 1978. “Mozart und der Vers.” In Analecta Musicologica, Vol. 18: Colloquium Mozart und Italien (1974: Rom), edited by Friedrich Lippmann, 107–37. Cologne: A. Volk.

Locke, Ralph P. 2009. Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mahling, Christoph-Hellmut. 1973. “Die Gestalt des Osmin in Mozarts Entführung. Von Typus zur Individualität.” Archiv für Musikwissenschaft 30: 96–108.

Malin, Yonatan. 2010. Songs in Motion: Rhythm and Meter in the German Lied. New York: Oxford University Press.

Melamed, Daniel. 2008. “Counterpoint in Mozart’s Die Entführung aus dem Serail.” Cambridge Opera Journal 20: 25–51.

Mirka, Danuta. 2008. “Metre, phrase structure, and manipulations of musical beginnings.” In Communication in Eighteenth-Century Music, edited by Danuta Mirka and Kofi Agawu, 83–111. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mirka, Danuta. 2009. Metric Manipulations in Haydn and Mozart: Chamber Music for Strings, 1787–1791. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mirka, Danuta. 2010. “Punctuation and Sense in Late-Eighteenth-Century Music.” Journal of Music Theory 54: 235–82.

Platoff, John. 1990. “The Buffa Aria in Mozart’s Vienna.” Cambridge Opera Journal 2: 99–120.

Ratner, Leonard G. 1980. Classic Music: Expression, Form, and Style. New York: Schirmer Books.

Reiber, Joachim. 1994. “Singspiel.” In Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart: allgemeine Enzykolpädie der Musik—Sachteil, 2nd ed., vol. 8. Kassel: Bärenreiter.

Rodgers, Stephen. 2011. “Thinking (and Singing) in Threes: Triple Hypermeter and the Songs of Fanny Hensel.” Music Theory Online 17.

Rothstein, William. 1989. Phrase Rhythm in Tonal Music. New York: Schirmer Books.

Rothstein, William. 2008. “National metrical Types in Music of the Eighteenth and Early-Nineteenth Centuries.” In Communication in Eighteenth-Century Music, edited by Danuta Mirka and Kofi Agawu, 112–59. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rothstein, William. 2011. “Metrical Theory and Verdi’s Midcentury Operas.” Dutch Journal of Music Theory 16: 93–111.

Rumph, Stephen. 2005. “Mozart’s Archaic Endings: A Linguistic Critique.” Journal of the Royal Musical Association 130: 159–96.

Schachter, Carl. 1999. “The Adventures of an F-sharp: Tonal Narration and Exhortation in Donna Anna’s First-Act Recitative and Aria.” In Unfoldings: Essays in Schenkerian Theory and Analysis, edited by Joseph N. Straus, 221–35. New York: Oxford University Press.

Schaubhut Smith, Judyth, et al., translators. 1991. The Metropolitan Opera Book of Mozart Operas. New York: Harper Collins.

Schubart, C. D. F. 1806. Ideen zu einer Ästhetik der Tonkunst. Vienna. Reprinted Hildesheim: G. Olms, 1975.

Temperley, David. 2001. The Cognition of Basic Musical Structures. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Temperley, David. 2008. “Hypermetrical Transitions.” Music Theory Spectrum 30, 305–25.

Tyler, Linda. 1991. “Bastien und Bastienne and the Viennese Volkskomödie.” Mozart Jahrbuch: 576–79.

Webster, James. 1991. “The Analysis of Mozart’s Arias.” In Mozart Studies, edited by Cliff Eisen, 101–99. New York: Oxford University Press.